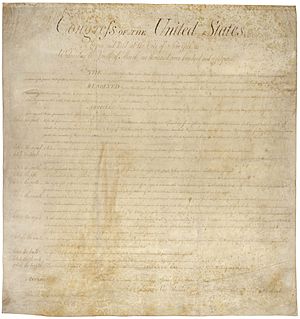

Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution facts for kids

The Fourth Amendment (also called Amendment IV) is a very important part of the United States Constitution. It is found in the Bill of Rights. This amendment protects you from the government searching your property or taking your belongings without a good reason.

It says that the government cannot do "unreasonable searches and seizures." A "seizure" means taking someone's property. The amendment also explains when a special paper called a warrant can be issued. A warrant is like a permission slip from a judge.

For a warrant to be valid, a judge must approve it. The police or government officials must have a strong reason, called "probable cause," to believe a search is needed. They also have to promise under oath that their reasons are true. The warrant must clearly describe the exact place to be searched and what they expect to find or take.

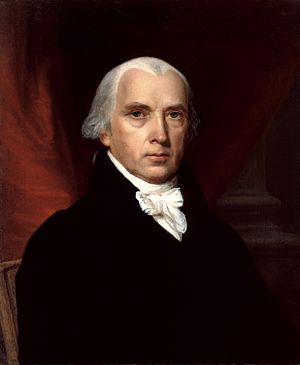

James Madison introduced the Fourth Amendment to Congress in 1789. It was part of the Bill of Rights, which was created to address concerns about the new Constitution. The states approved it by December 15, 1791. On March 1, 1792, it officially became part of the Constitution.

For a long time, the Fourth Amendment mostly applied to the federal government. There weren't many important court cases about it until the 1900s.

Contents

What the Fourth Amendment Says

The actual words of the Fourth Amendment are:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

This means that people have a right to feel safe. They should feel safe in their bodies, homes, papers, and other belongings. The government cannot search or take these things without a good reason. If a warrant is needed, it must be based on "probable cause." This means there must be strong evidence. The person asking for the warrant must swear an oath. The warrant must also clearly describe the place to be searched. It must also describe the people or things to be taken.

How the Fourth Amendment Came About

Ideas from English Law

Many ideas in American law, including the Fourth Amendment, come from English law. A famous English judge, Sir Edward Coke, said in 1604 that "The house of every one is to him as his castle." This means your home is your private space. The king or government could not just enter someone's home without a good reason. They needed a warrant for lawful searches.

In the 1760s, people in England started fighting against "general warrants." These warrants allowed government officials to search anywhere for anything. A famous case was Entick v Carrington in 1765. Government officials searched John Entick's home and took all his papers. They did not have a specific reason. The court ruled that this search was against the law. The judge said that "Our law holds the property of every man so sacred." This case helped set the rule that the government cannot just intrude on private property.

Rules in Colonial America

Homes in Colonial America were not as protected as in England. British laws allowed officials to search homes easily. This was often to collect taxes. Before 1750, the only type of warrant used was the general warrant. This meant officials had almost unlimited power to search.

In 1756, the colony of Massachusetts made a law against general warrants. This was the first American law to limit search powers. It happened because people were very upset about the Excise Act of 1754. This act gave tax collectors huge powers. It also allowed "writs of assistance." These were general warrants that let tax collectors search homes for any "prohibited" goods.

A big problem started in 1760 when King George II died. All writs of assistance would expire. In 1761, a group of merchants asked the court to stop these writs. James Otis, a lawyer, strongly argued against them. He called British policies, including general warrants, unfair. Even though the court ruled against Otis, his speech was very important. Future President John Adams said it was "the spark in which originated the American Revolution."

Otis was later elected to the Massachusetts legislature. He helped pass a law that required specific warrants. These warrants had to be approved by a judge. They also had to be based on information sworn under oath. However, the governor stopped this law. He said it went against English law.

Seeing the danger of general warrants, the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) clearly banned them. This became a model for the Fourth Amendment. It stated:

That general warrants, whereby any officer or messenger may be commanded to search suspected places without evidence of a fact committed, or to seize any person or persons not named, or whose offense is not particularly described and supported by evidence, are grievous and oppressive and ought not to be granted.

Later, in 1780, John Adams wrote Article XIV of the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights. This added the idea that all searches must be "reasonable." It also served as another basis for the Fourth Amendment's language. It said:

Every subject has a right to be secure from all unreasonable searches, and seizures of his person, his houses, his papers, and all his possessions. All warrants, therefore, are contrary to this right, if the cause or foundation of them be not previously supported by oath or affirmation; and if the order in the warrant to a civil officer, to make search in suspected places, or to arrest one or more suspected persons, or to seize their property, be not accompanied with a special designation of the persons or objects of search, arrest, or seizure: and no warrant ought to be issued but in cases, and with the formalities, prescribed by the laws.

By 1784, eight states had rules against general warrants in their constitutions.

Creating and Approving the Amendment

After the Articles of Confederation proved too weak, a new Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787. They proposed a new Constitution with a stronger government. George Mason, who helped write Virginia's Declaration of Rights, suggested adding a bill of rights. This would list and protect people's freedoms. Other delegates, including James Madison, disagreed at first. They thought existing state laws were enough. They also worried that listing some rights might mean other rights were not protected. Mason's idea was voted down.

For the Constitution to become law, nine of the thirteen states had to approve it. Many people, called "Anti-Federalists," opposed the Constitution. They were worried because it did not have enough guarantees for civil liberties. To get the Constitution approved, its supporters in states like Virginia and Massachusetts made a deal. They agreed to approve the Constitution if a bill of rights was added later. Four states specifically asked for limits on the government's power to conduct searches.

In the 1st United States Congress, James Madison proposed twenty amendments. These were based on state bills of rights and English laws. One amendment required "probable cause" for government searches. Congress then shortened Madison's twenty ideas to twelve. They also changed some of the wording about searches and seizures. The final twelve amendments were sent to the states for approval on September 25, 1789.

By this time, opinions had changed. Many Federalists, who had been against a Bill of Rights, now supported it. They saw it as a way to calm the Anti-Federalists. Many Anti-Federalists, however, now opposed it. They realized that adding the Bill of Rights would make it harder to have another convention to change the Constitution more.

New Jersey was the first state to approve the Fourth Amendment on November 20, 1789. Maryland, North Carolina, and South Carolina followed. New Hampshire and Delaware also approved it. This brought the total to six states. The process then slowed down. Connecticut and Georgia thought a Bill of Rights was not needed. Massachusetts approved most amendments but did not send official notice.

Later, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island approved the Fourth Amendment. When Vermont joined the Union in 1791, the number of states needed for approval went up to eleven. Vermont approved all twelve amendments on November 3, 1791. Virginia finally approved them on December 15, 1791. On March 1, 1792, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson announced that the ten successfully approved amendments were now part of the Constitution.

Images for kids

-

Potter Stewart wrote an important court decision that expanded Fourth Amendment protections to electronic surveillance.

See also

In Spanish: Cuarta Enmienda a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Cuarta Enmienda a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos para niños

- Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights

- Fourth Amendment Protection Act

- NSA warrantless surveillance (2001–07)#Fourth Amendment issues

- Parallel construction

- Privacy laws of the United States

- Special needs exception

- Section Eight of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- subpoena ad testificandum

- subpoena duces tecum

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |