Parliament of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Parliament of England |

|

|---|---|

Royal coat of arms of England, 1558–1603

|

|

| Type | |

| Type |

Unicameral

(1215–1341 / 1649–1657) Bicameral (1341–1649 / 1657–1707) |

| Houses | Upper house: House of Lords (1341–1649 / 1660–1707) House of Peers (1657–1660) Lower house: House of Commons (1341–1707) |

| History | |

| Established | 15 June 1215 (Lords only) 20 January 1265 (Lords and elected Commons) |

| Disbanded | 1 May 1707 |

| Preceded by | Curia regis |

| Succeeded by | Parliament of Great Britain |

| Leadership | |

|

William Cowper1

Since 1705 |

|

|

John Smith1

Since 1705 |

|

|

|

|

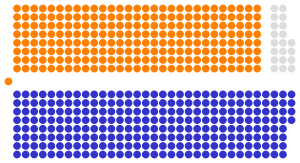

House of Commons political groups

|

Final composition of the English House of Commons: 513 Seats Tories: 260 seats Whigs: 233 seats Unclassified: 20 seats |

| Elections | |

| Ennoblement by the Sovereign or inheritance of an English peerage | |

| First past the post with limited suffrage1 | |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| Palace of Westminster, Westminster, London | |

| Footnotes | |

| 1Reflecting Parliament as it stood in 1707.

See also: Parliament of Scotland, Parliament of Ireland |

|

The Parliament of England was the main law-making group, or legislature, for the Kingdom of England from the mid-1200s to the 1700s. It started in 1215 with the signing of the Magna Carta. This important document gave wealthy landowners, called barons, the right to advise the king.

In 1295, Parliament grew to include nobles, bishops, and two representatives from each county and town in England and Wales. This setup became the model for all future Parliaments. Over the next 100 years, Parliament split into two parts: the House of Lords for nobles and bishops, and the House of Commons for knights and local representatives called "burgesses."

During the time of King Henry IV, Parliament's role expanded. It no longer just decided on taxes. People could now ask Parliament to fix problems in their local areas. Citizens also gained the power to vote for their representatives in the House of Commons.

In 1066, William the Conqueror brought in a feudal system. This meant he asked for advice from a council of important landowners and church leaders before making laws. In 1215, these landowners made King John agree to the Magna Carta. This document said the king could not collect new taxes without his royal council's approval. This council slowly grew into Parliament. Over many centuries, the English Parliament gradually limited the power of the English monarchy. This process led to big events like the English Civil War.

Contents

How Parliament Began and Grew

Early Councils and Royal Power

Kings of England needed support from powerful people to rule. They didn't have a large army or police force. Under the feudal system after the Norman Conquest in 1066, kings relied on nobles and church leaders. Nobles had wealth and military power from their land. The Church had its own legal system.

To get advice and agreement from these powerful groups, kings held "Great Councils." These councils usually included archbishops, bishops, abbots, barons, and earls. These were the main people in the feudal system.

If the king and these councils disagreed, it was hard for the government to work. For example, Thomas Becket and King Henry II had a big fight over church power. King John also angered many nobles, who then forced him to sign the Magna Carta in 1215. When John refused to follow it, a civil war started.

The Great Council Becomes Parliament

The Great Council slowly changed into the Parliament of England. The word "Parliament" came from Latin and French words meaning "discussion" or "speaking." It first appeared in official papers in the 1230s. Early parliaments not only made laws but also acted like a court.

In the 1200s and 1300s, kings sometimes called "Knights of the Shire" to meet. For instance, in 1254, county leaders were told to send knights to Parliament to advise the king on money matters.

At first, parliaments were mostly called when the king needed to raise money through taxes. After the Magna Carta, this became a common rule. This was partly because King John died in 1216, and his young son, Henry III, became king. Powerful nobles and church leaders ruled for Henry until he was old enough. They liked this power and made sure the Magna Carta was followed.

Parliament Under Henry III

When Henry III took full control, nobles worried he wasn't asking for their advice. They also felt he favored his foreign relatives. His support for a costly war in Sicily was the final straw. In 1258, seven leading barons made Henry promise to follow the "Provisions of Oxford." These rules limited the king's power and gave power to a council of fifteen barons. Parliament was set to meet three times a year to check on them.

Simon de Montfort, a French-born nobleman, led this rebellion. In 1264, Montfort defeated and captured King Henry III at the Battle of Lewes. Montfort then called the first Parliament without the king's permission. He invited archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, barons, and, for the first time, two knights from each shire and two "burgesses" from each town. This was a way for Montfort to gain support and show his authority.

This Parliament met in early 1265. Even though Montfort was later defeated and killed, his idea of including knights and burgesses was adopted by King Edward I in 1295. This became known as the "Model Parliament." The attendance of knights and burgesses became known as the summoning of "the Commons." This term came from the French word "commune," meaning "community of the realm."

Parliament Becomes a Stronger Institution

During the reign of King Edward I, starting in 1272, Parliament's role grew. Edward wanted to unite England, Wales, and Scotland. He also wanted to avoid rebellions like his father faced. So, Edward encouraged everyone to send petitions to Parliament about their problems. This made people feel like they had a say in government.

As more petitions came in, government officials handled them to keep Parliament focused on other business. However, these petitions showed that Parliament was becoming a place where ordinary people's concerns could be heard. This tradition of petitioning continues today in the UK Parliament.

From Edward's time, Parliament's power depended on how strong or weak the king or queen was. A strong ruler could pass laws easily. Sometimes, they even tried to bypass Parliament, especially for money laws, but the Magna Carta made it hard to do so without Parliament's approval. When rulers were weak, Parliament often became a place of opposition.

The people called to Parliament also changed. Nobles and senior clergy were always there. From 1265, knights and burgesses were usually called when the king needed money. But if the king only wanted advice, he might only call nobles and clergy. It wasn't until the mid-1300s that calling representatives from shires and towns became normal for all parliaments.

A key moment for Parliament was the removal of King Edward II. Whether he was removed in Parliament or by Parliament, this event showed Parliament's growing importance. Parliament also helped make his son, Edward III, the new king.

In 1341, the Commons met separately from the nobles and clergy for the first time. This created two separate chambers: the House of Lords (for nobles and clergy) and the House of Commons (for knights and burgesses). Together, they became known as the Houses of Parliament.

Parliament's power grew under Edward III. It was decided that no law could be made, and no tax collected, without the agreement of both Houses and the King. This happened because Edward III was fighting the Hundred Years' War and needed money. He tried to avoid Parliament, which led to this new rule.

The Commons became bolder during this time. In 1376, their leader, Sir Peter de la Mare, complained about high taxes and demanded to see how royal money was spent. The Commons even tried to remove some of the king's ministers. Though the Speaker was jailed, he was soon released. Under King Richard II, the Commons again tried to remove ministers. They insisted they could control not just taxes, but also how public money was spent. Still, the Commons were less powerful than the House of Lords and the King.

During this period, voting rights for the House of Commons were limited. From 1430, only men who owned property worth 40 shillings or more could vote. This was called the "Forty Shilling Freeholders" rule.

King, Lords, and Commons: A New Structure

The Tudor Era and Parliament's Role

During the time of the Tudor monarchs, the modern structure of the English Parliament began to form. Tudor kings and queens were powerful. Sometimes, Parliament didn't meet for several years. However, Tudor rulers were smart enough to know they needed Parliament to make their decisions seem fair, especially when raising taxes. So, they made it a rule that monarchs would call and close Parliament when they needed it.

By the time Henry VII became king in 1485, the monarch was not a member of either the House of Lords or the House of Commons. The king or queen would share their ideas through their supporters in both houses. A "Speaker" led the discussions in the House of Commons. This Speaker had to deliver any bad news from the Commons to the monarch. This is why, even today, the Speaker is traditionally "dragged" to their chair by other members after being elected.

Any member could propose a "bill" to Parliament. Bills supported by the monarch were often suggested by members of the Privy Council who were also in Parliament. For a bill to become law, it needed to be approved by both Houses and then by the monarch. The monarch could say "no" (veto) to a bill. This happened several times in the 1500s and 1600s. While a monarch can still veto a law today, it hasn't happened since 1707.

When a bill became law, it meant the King, Lords, and Commons all approved it. But this was not a truly democratic process. Only a small number of adult men could vote for the House of Commons, perhaps as little as three percent. There was also no secret ballot. This meant powerful local people could control elections, as many voters depended on them or could be influenced by money.

The Palace of Westminster became the permanent home of the English Parliament. In 1548, the House of Commons was given St Stephen's Chapel as a meeting place. This chapel became a debating room. Its unique shape, like choir stalls in a chapel, influenced how the British Parliament sits today. Members of the ruling party sit on the Speaker's right, and opposition members sit on the left.

Under King Henry VIII, the number of church leaders (Lords Spiritual) in the House of Lords decreased. This happened because Henry closed many monasteries. For the first time, the noble lords (Lords Temporal) were more numerous than the church lords.

The Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–42 made Wales part of England. This brought Welsh representatives into the Parliament of England, starting in 1542.

Rebellion and Revolution: Parliament's Fight for Power

Challenges to the Monarchy

Parliament didn't always agree with the Tudor monarchs. But criticism of the king reached new levels in the 1600s. When the last Tudor ruler, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James I of Scotland became king, starting the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, worried about the king's power, the House of Commons gave King Charles I the Petition of Right. This document demanded that their freedoms be restored. Charles accepted it but later dissolved Parliament and ruled alone for eleven years. He was only forced to call Parliament again in 1640 because he needed money after expensive wars. This led to the Short Parliament and the Long Parliament.

The Long Parliament had many critics of the king, like John Pym. Tensions grew until January 1642, when Charles I tried to arrest Pym and four other members in the House of Commons. But the members had been warned and were gone. Charles was further embarrassed when the Speaker, William Lenthall, refused to say where they were.

Relations between the king and Parliament worsened. When problems arose in Ireland, both Charles and Parliament raised armies. Soon, it was clear these armies would fight each other. This led to the English Civil War in October 1642. Those who supported Parliament were called Parliamentarians or Roundheads.

The English Republic and Cromwell

Battles between the King and Parliament continued. Parliament was no longer weaker than the monarchy. This change was clear when Charles I was executed in January 1649. This event was not started by elected representatives. In December 1648, the New Model Army removed members of Parliament who didn't support them. The remaining "Rump Parliament" put the king on trial for treason. This led to his execution and the start of an 11-year republic. The House of Lords was abolished, and the Rump Parliament ruled England until 1653.

In 1653, army chief Oliver Cromwell dissolved the Rump Parliament. He later called other parliaments, including the Barebone's Parliament and the First Protectorate Parliament.

Even though the English Republic (1649-1660) was sometimes like a military rule under Cromwell, it was very important for Parliament's future. First, members of the House of Commons became known as "MPs" (Members of Parliament). Second, Cromwell gave his parliaments a lot of freedom, even though he often dissolved them when they disagreed with him.

In 1653, Cromwell became head of state as Lord Protector. The Second Protectorate Parliament offered him the crown, but he refused. However, the government structure he helped create became the basis for future parliaments. It included an elected House of Commons, a House of Lords, and a constitutional monarchy (a king or queen whose power is limited by laws) at the top. In 1657, Cromwell united the Parliament of Scotland with the English Parliament.

The Rump Parliament (1649-1653) showed that Parliament could exist without a king or a House of Lords. Future English monarchs never forgot this. Charles I was the last English monarch to enter the House of Commons. Even today, during the State Opening of Parliament, a Member of Parliament is sent to Buckingham Palace as a symbolic "hostage" to ensure the monarch's safe return. When the monarch signals for the House of Commons to come to the House of Lords, the doors to the Commons chamber are slammed shut in the face of the "Black Rod" (the Queen's representative). This symbolizes the Commons' right to debate without the monarch's presence.

From Restoration to Union: Parliament's Final Form

The Monarchy Returns

The big changes between 1620 and 1689 all happened in the name of Parliament. Parliament's new status as the main government body was confirmed when the monarchy was brought back in 1660. After Oliver Cromwell died, his son Richard became Lord Protector. But his Parliament was dissolved. The Rump Parliament was recalled, then dissolved again.

Finally, General George Monck marched his army from Scotland into England. He recalled the Long Parliament, which then voted to dissolve itself and call new elections. These elections were very democratic for the time, though still only a few people could vote. This led to the Convention Parliament (1660), which was mostly made up of royalists. This Parliament voted to bring back the monarchy and the House of Lords. Charles II returned to England as king in May 1660. The union of the Scottish and English Parliaments that Cromwell had created was ended in 1661.

The Restoration started the tradition that all governments needed Parliament's approval to be legitimate. In 1681, Charles II dissolved Parliament and ruled alone for four years. This followed big disagreements between him and Parliament. Charles took a risk, but he was right that the country didn't want another civil war. Parliament disbanded without a fight.

The Glorious Revolution and Limited Monarchy

Charles II died in 1685, and his brother James II became king. Charles had secretly been Catholic, but James was openly Catholic. He tried to let Catholics hold public jobs, which Protestants strongly opposed. They invited William of Orange, a Protestant who was married to James II's daughter Mary, to invade England and claim the throne.

William landed in England in November 1688 with an army. Many Protestant officers left James's army to join William. James fled the country. Parliament then offered the crown to his Protestant daughter Mary. Mary refused, so William and Mary ruled together. As part of this agreement, called the Glorious Revolution, Parliament passed the Bill of Rights in 1689. Later, the Act of Settlement was approved in 1701. These laws officially made Parliament the most important power in England for the first time. These events marked the start of England's constitutional monarchy, where the monarch's power is limited by laws made by Parliament.

The Birth of Great Britain's Parliament

After the Treaty of Union in 1707, the Parliaments of England and Scotland passed Acts of Parliament that created a new Kingdom of Great Britain. Both parliaments were dissolved, and a new Parliament of Great Britain was formed. This new Parliament met in the same place as the old English Parliament. The Parliament of Great Britain later became the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1801, when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was formed.

Other Places Parliament Met

- York, various times

- Lincoln, various times

- Oxford, 1258 (the "Mad Parliament"), 1681

- Kenilworth, 1266

- Acton Burnell Castle, 1283

- Shrewsbury, 1283 (for the trial of Dafydd ap Gruffydd)

- Lincoln, 1301

- Carlisle, 1307

- Northampton, 1328

- New Sarum (Salisbury), 1330

- Winchester, 1332, 1449

- Leicester, 1414, 1426

- Reading Abbey, 1453

- Coventry, 1459

Cities Outside England Represented in Parliament

Two cities that were once part of France but were controlled by England also had representatives in the English Parliament:

- Calais, from 1372 to 1558.

- Tournai, from 1513 to 1519 (now in Belgium).

Images for kids

-

Between 1352 and 1396, the House of Commons met in the chapter house of Westminster Abbey.

-

Queen Elizabeth I presiding over Parliament, between 1580 and 1600.

-

The interior of Convocation House, which was formerly a meeting chamber for the House of Commons during the English Civil War and later in the 1660s and 1680s.

See also

In Spanish: Parlamento de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Parlamento de Inglaterra para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |