William the Conqueror facts for kids

Quick facts for kids William I |

|

|---|---|

| King of England, Duke of Normandy | |

William I the Conqueror, King of England. (British Library, MS Royal 14 C VII f.8v)

|

|

| King of England | |

| Reign | 25 December 1066 - 9 September 1087 |

| Coronation | 25 December 1066 |

| Predecessor | Harrold II (Godwinson) |

| Successor | William II |

| Born | c. 1027 Normandy |

| Died | 9 September 1087 (aged c. 60) Rouen, Normandy |

| Consort | Matilda of Flanders (1031 – 1083) |

| House | House of Normandy |

| Father | Robert I, Duke of Normandy |

| Mother | Herleva |

William the Conqueror (born around 1027, died 1087), also known as William I of England, was the first Norman King of England. He ruled from 1066 until his death in 1087. Before becoming king, he was the Duke of Normandy starting in 1035.

William is famous for winning the Battle of Hastings. In this battle, he defeated Harold Godwinson, who was the last Anglo-Saxon king of England. This important event is shown on the Bayeux Tapestry. William's victory changed the history of both Normandy and England forever.

Contents

William's Early Life

William was born in Falaise, Normandy, around 1027 or 1028. His father was Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and his mother was Herleva. When William's father died in 1035, William became the Duke of Normandy. He was still very young, only about eight years old.

Before his death, Duke Robert wanted to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He made his noblemen promise to accept his young son William as their duke if he did not return.

Challenges as a Young Ruler

William's time as a young duke was very difficult. Many Norman nobles did not want a child as their leader. Robert II, Archbishop of Rouen, a powerful church leader, protected William. King Henry I of France also supported William.

However, Archbishop Robert died in 1037. Without his support, the Norman nobles started fighting among themselves. Some even tried to kill William. His servants were killed, and Normandy became very chaotic.

In 1042, William held a church council in Normandy. At this meeting, the church created a new rule called the Truce of God. This rule was meant to stop private wars. It said that no fighting was allowed on feast days, fast days, or from Thursday night until Monday morning. Breaking this truce meant being kicked out of the church. William likely became an adult ruler around 1044. He no longer needed tutors and could rule on his own.

Duke of Normandy's Rise

The Battle of Val-ès-Dunes

Private wars continued in Normandy even after William became an adult. By 1046, many powerful families in lower Normandy planned to replace William as duke. Guy of Burgundy, William's cousin, was given castles by William but wanted to rule Normandy himself. He led a rebellion against William.

William realized this was a serious threat and asked King Henry I of France for help. The French king quickly arrived with a large army. The combined armies of Duke William and King Henry fought the rebels at Val-ès-Dunes. The rebels were defeated, and Guy fled. William then surrounded Guy's castle until he surrendered in 1049. William forgave his cousin, and Guy returned to Burgundy. This victory helped William gain more control over Normandy.

After the battle, another church council met in October 1047. They made the Truce of God even stricter. No private wars were allowed from Wednesday evening through Monday morning, or during important church seasons like Advent, Lent, Easter, and Pentecost. However, the king and duke were allowed to fight during these times to keep the peace. This meant William's rule in Normandy was now supported by the church.

Building Power and Facing Enemies

The Battle of Val-ès-Dunes was the start of William's journey to power. While King Henry's help was important, William's own nobles began to see him as a strong leader. He then decided to marry Matilda of Flanders around 1049. She was the daughter of Baldwin V, Count of Flanders.

At first, Pope Leo IX did not allow the marriage, possibly because William and Matilda were cousins. But they married anyway between 1050 and 1052. Later, in 1059, another pope, Nicholas II, finally approved their marriage.

As William grew stronger in Normandy, things changed around him. King Henry I, who had supported William, suddenly became his enemy around 1052. At the same time, two of William's uncles, Archbishop Mauger and Count William of Arques, rebelled against him. William fought his uncle at the castle of Arques. King Henry then brought a large army into Normandy to help William of Arques. But Duke William defeated the king's army. Without the king's help, the castle surrendered. Duke William sent his two rebellious uncles away from Normandy.

In 1054, King Henry I again invaded Normandy with a large army. This time, William had the full support of Normandy. He made sure that anything that could be used for food was removed from the path of the French armies. This made it hard for them to feed their soldiers. William also divided his own soldiers into two armies. William's forces watched the king's armies, waiting for a chance to attack.

One part of the French army, led by King Henry's brother Odo, found plenty of food and drink in the town of Mortimer. They relaxed and enjoyed themselves. William's second army surprised them and destroyed most of Odo's soldiers. When the king heard that his brother's army was destroyed, his own army panicked. The king and his men left Normandy as fast as they could.

King Henry I agreed to a peace that lasted three years. But in 1058, the king broke the peace and invaded Normandy again. William waited for the best time to attack. This happened when the French army was crossing the Dives river at Varaville. The king had already crossed the river and watched as his army was destroyed while entering the water. He took what was left of his army and left Normandy for good. The king died a short time later. The new king of France, his young son Phillip, was under the care of William's father-in-law, Baldwin V. This meant France was no longer a threat to Normandy, allowing William to expand his power.

Normandy and England's Connection

In 1002, Ethelred the Unready, King of England, married Emma, who was the sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy. This marriage created a strong link between England and Normandy. Later, when Canute became King of England in 1016, he also married Emma of Normandy. Her two sons from her first marriage fled to Normandy for safety. Edward the Confessor, the older son, lived in Normandy for many years at the court of the dukes. William, his cousin, was the last duke to protect him there.

Edward became King of England in 1042. In 1052, King Edward promised William that he would be his heir. In 1065, Harold Godwinson visited Normandy. While there, he promised Duke William that he would support him as the next King of England.

On January 5, 1066, King Edward died. But Harold did not keep his promise. The very next day, Harold Godwinson was crowned King of England. The story was that on his deathbed, King Edward had changed his mind and promised Harold the throne. Harold was not from a royal family and had no legal right to the throne. William had likely known Edward was dying, but the news of Harold taking the throne must have been a big surprise to many.

Norman Invasion of England

Preparing for Invasion

William started planning his invasion as soon as he heard the news from England. He called a meeting of his most important men. William planned to gather a large army from all over France. His power and wealth meant he could prepare a huge military operation. His first job was to build a fleet of ships to carry his army across the English Channel. Then he began gathering soldiers. His friendships with Brittany, France, and Flanders meant he could get soldiers from many parts of Europe. William also asked for and received the support of the pope, who gave him a special banner to carry into battle.

At the same time William was planning his invasion, Harold Hardrada, the King of Norway, was also planning to invade England. King Harold of England knew both would be coming. He kept his ships and soldiers in the south of England, where William might land.

William's invasion fleet may have had as many as 1,000 ships. They had good winds to leave Normandy on the night of September 27, 1066. William's ship, the Mora, was a gift from his wife, Matilda. It led the fleet to land at Pevensey the next morning.

As soon as he landed, William heard news of King Harold's victory over the Norwegian king at Stamford Bridge in northern England. Harold also heard that William had landed at Pevensey. He marched his army south as quickly as he could. The king rested in London for a few days before taking his army to meet William and his French forces.

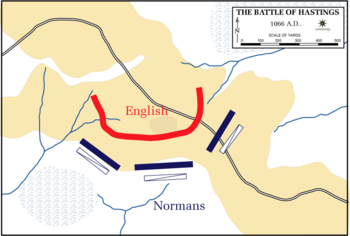

The Battle of Hastings

King Harold's army took a strong position on a hill called Senlac Hill, north of Hastings. They saw the Norman army marching up the valley towards them. Harold had more soldiers, but they were tired from their fast march from London.

William formed his lines at the bottom of the hill, facing the English "shield wall." He sent his archers halfway up the slope to shoot at the English. He also sent his mounted knights to the left and right to find weak spots. At first, William's knights tried to break through the shield wall with the force of their horses. But they were attacking uphill and could not go fast enough. Harold's front line stood firm and stopped all attacks.

William's army began to fall back, and rumors spread that Duke William was dead. William took off his helmet so his men could see he was still alive. When William saw that many of Harold's men were following his knights down the hill, he used a trick he had learned before. He suddenly turned and charged the English foot soldiers who were chasing them. The English had no chance against mounted knights.

This trick worked at least two more times during the battle and made Harold's shield wall weaker. Then William tried something new. Instead of separate attacks by knights and archers, he used them together. His archers, who had not succeeded against the shield wall before, now shot their arrows high into the air. The arrows came down on top of the English soldiers. This might be how King Harold was killed by an arrow through his eye.

The shield wall finally broke, and the Normans overwhelmed the English. By nightfall, many English soldiers were dead on the field or being hunted down by William's troops. William called his troops back, and they all spent the night camped on the battlefield.

After the Battle

The battle was won, but the English still had smaller armies that had not joined King Harold at Hastings. They had lost their king but were still trying to get organized. William rested his army for five days before moving towards London. His march took him through several towns that he either captured or destroyed.

When William reached London, the English resisted for a short time but eventually surrendered. On Christmas Day in 1066, William was crowned King of England. His victory at Hastings earned Duke William the nickname he has been known by ever since: 'William the Conqueror'.

King of England

Starting His Reign

William chose to be crowned on Christmas Day. He thought the English would be less likely to cause trouble on such an important feast day. He also believed it was God's will for him to be king.

After his coronation, William spent a few months in England. He then returned to Normandy, leaving England in the hands of two trusted men: his half-brother Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux, and William FitzOsbern. Odo became the Earl of Kent, and FitzOsbern became the Earl of Hereford. The three remaining English earls were allowed to keep their positions.

When William sailed back to Normandy, he took many of his followers with him. This included soldiers who had been paid and others he wanted to keep an eye on. He also brought the English Archbishop Stigand and Edgar the Atheling. He also took his remaining three English earls, Edwin, Morcar, and Waltheof. This was to prevent any of them from starting a revolt while he was away. William had duties in Normandy to take care of, and many of his soldiers needed to return to keep his duchy safe.

When William returned to London in December 1067, he learned about problems that had come up while he was gone. Hertfordshire had been attacked by people from Mercia. Then Exeter refused to accept the new king's rule. William raised money from parts of England that would pay and called upon English soldiers. Exeter surrendered after one of its hostages was blinded. After he took control of Devon and Cornwall, things seemed quiet. At Winchester, William sent for his wife Matilda, who was crowned Queen of England there at Pentecost.

Rebellions and Control

By summer, more rebellions had broken out. At the same time, some people were fleeing England. Edgar Atheling, along with his mother and sisters, went to Scotland, where they were welcomed. In the North, strong groups against the Normans were gathering around York. Earl Edwin and his brother Morcar left William's court to join the rebels in the north.

William then built a castle at Warwick. This caused the Earls and others to surrender to William. More castles were built. William then entered York, where others came to him and submitted. He then talked with the king of Scots to prevent any invasions of England from the north. But his campaign in the North was not as effective as he thought. In 1069, a second uprising turned into a war. The men William had left in charge were killed. A small Norman force was holding out in York when William came to help them. After building another castle, William left Earl William FitzOsbern in charge. For the next five months, the north was quiet.

However, the northern English leaders had sent a message to King Sweyn of Denmark, offering him the crown if he could defeat the Normans. Sweyn sent a Danish fleet to England.

In the summer of 1069, the Danish fleet appeared off the coast of Kent. It moved up the coast towards the north, attacking as it went. William and his army were in the south, guarding against any attacks. Finally, the fleet joined the English rebels on the banks of the River Humber. The remaining English earls all left William and joined the combined English-Danish forces. They attacked the Norman garrison at York and killed almost everyone, except a few women and children. William Malet, a Norman who had lived in England before 1066, was also spared.

The Harrying of the North

William's northern army was destroyed, and York was in ruins. At the same time, smaller rebellions were breaking out in Wales and southwest England. William knew he was in trouble. He gathered all his commanders and troops to combine his forces. The king knew that with a smaller army, he had to deal with one group of rebels at a time.

He sent William FitzOsbern and Brian of Brittany to deal with Exeter. William himself fought an army moving in from the east. In both cases, the Norman armies won. He then moved on the northern armies that had destroyed York. But he could not get any farther north than Pontefract. After trying for several weeks, William paid the Danish Fleet to leave York for the winter. They agreed and returned to the mouth of the Humber to stay there for the winter.

William was now able to move up to York. He rebuilt the castles there. He then had his forces spread out and destroy everything useful for the English and Danish army to feed themselves. This caused widespread famine, and the people of the area either left or starved to death. This was William's famous "harrying of the North."

The result of all this was the surrender of his English Earls and most of the rebels in England. The few remaining groups were quickly crushed by William's army. But one group was more stubborn. This was at Chester. After a difficult march during winter, William surprised them before they were ready. After their surrender, he built two more castles there and then returned to Winchester.

Ruling England and Normandy

William never again had to destroy a county as he did to Yorkshire. He had dealt with the main threats to his rule, but some problems were only partly solved. The Danish fleet came back in 1070, this time led by King Sweyn. They joined a small group of rebels on the Isle of Ely led by Hereward the Wake. Again, William paid the Danes to leave and then dealt with the rebels. Hereward was never heard from again.

William now had to rule both England and Normandy. He found he had to be present in both places to keep things under control. When he was in Normandy, trouble often broke out in England. When he was in England, Normandy was ruled by his wife Matilda. But Fulk Rechin, the new count of Anjou, had taken Maine from William's control. William had to take it back in 1073.

In 1082, William arrested his half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent. The reasons are not fully clear, but Odo was trying to raise an army to march on Rome. His plan was to become the next Pope. William put him on trial on the Isle of Wight. Among other crimes, Odo was accused of trying to raise an army from William's soldiers. William pointed out that these soldiers were needed to defend England. Odo argued that only the Pope could judge him as a bishop. William replied that he was not seizing a bishop, but seizing his earl, whom he had left in charge during his absence. Odo was imprisoned in Normandy for the rest of his life.

In 1083, Queen Matilda died and was buried in Caen. William and Matilda had been very close. Their only disagreement was over their son Robert Curthose. Robert had rebelled against his father many times but kept in contact with his mother. This caused some tension between William and Matilda. Philip I of France found it difficult that his vassal (William) had become a king like himself, and so he disliked William. King Philip was not strong enough to fight William directly, so when Robert Curthose rebelled against his father, King Philip helped him.

In the summer of 1085, William learned that Canute IV of Denmark was preparing a fleet to sail against England. William returned to England in the autumn with many soldiers. He had to pay and feed them, which was very expensive. It may have been at this time that he realized he had no clear records of what was owed to him as king. He did not know if he was collecting all the taxes that were due.

The Domesday Book

At his Christmas court in Gloucester in 1085, William ordered a great survey to be taken in every part of England. The king wanted to know how many people lived in his [realm]. He wanted to know the size of every property, what each was worth, and how much income it brought in. No such survey had ever been made in England before. It was very detailed and important for English history. The Domesday Book was the first public record in England.

The information was written in two volumes. The first covered thirty-one counties and was called 'Great Domesday' because of its size. The second covered the counties of Essex, Norfolk, and Suffolk and was called 'Little Domesday'. The facts were recorded by several groups of bishops and earls. Each group collected information on several counties. William received a large collection of written records on August 1, 1086. This became the Domesday Book, though it would not be bound into books for almost another century.

William's Final Years

William died in Rouen, France, from injuries he received after falling off his horse.

William's Family

William and his wife Matilda of Flanders had at least nine children:

- Robert (born around 1050, died 1134), Duke of Normandy. He became duke after his father.

- Richard (born around 1052, died around 1075).

- William (born around 1055, died 1100). He became King of England after his father.

- Henry (born 1068, died 1135). He became King of England after his brother William.

- Agatha; she was promised to marry Alfonso VI of León and Castile but died before the wedding.

- Adeliza.

- Cecily (born around 1066, died 1127), abbess of Holy Trinity, Caen.

- Adela (died 1137), married Stephen I, Count of Blois.

- Constance (died 1090), married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany.

- Matilda.

Images for kids

-

Château de Falaise in Falaise, Lower Normandy, France; William was born in an earlier building here.

-

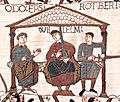

Image from the Bayeux Tapestry showing William with his half-brothers. William is in the centre, Odo is on the left with empty hands, and Robert is on the right with a sword in his hand.

-

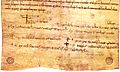

The signatures of William I and Matilda are the first two large crosses on the Accord of Winchester from 1072.

-

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry whose text indicates William supplying weapons to Harold during Harold's trip to the continent in 1064

-

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Normans preparing for the invasion of England

-

Modern day site of the Battle of Stamford Bridge

-

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the Battle of Hastings.

-

The remains of Baile Hill, the second motte-and-bailey castle built by William in York

-

Norwich Castle. The keep dates to after the Revolt of the Earls, but the castle mound is earlier.

-

The White Tower in London, begun by William

See also

In Spanish: Guillermo I de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Guillermo I de Inglaterra para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |