Edward III of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Edward III |

|

|---|---|

Edward III as head of the Order of the Garter, drawing c. 1430–1440 in the Bruges Garter Book

|

|

| King of England (more...) | |

| Reign | 25 January 1327 – 21 June 1377 |

| Coronation | 1 February 1327 |

| Predecessor | Edward II |

| Successor | Richard II |

| Born | 13 November 1312 Windsor Castle, Berkshire, England |

| Died | 21 June 1377 (aged 64) Sheen Palace, Richmond, London, England |

| Burial | 5 July 1377 Westminster Abbey, London |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Detail |

|

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | Edward II of England |

| Mother | Isabella of France |

Edward III (born 13 November 1312 – died 21 June 1377) was a powerful King of England. He ruled for 50 years, from January 1327 until his death in 1377. Edward is famous for his military victories. He also brought back strong royal power after his father, Edward II, had a difficult reign. Edward III turned England into one of Europe's strongest military nations.

His long reign saw important changes in laws and government, especially how the English Parliament grew. It also included the terrible time of the Black Death. Edward outlived his oldest son, Edward the Black Prince. So, the throne went to his grandson, Richard II.

Edward became king at age 14. This happened after his mother, Isabella of France, and her friend Roger Mortimer, removed his father from the throne. When Edward was 17, he led a successful takeover against Mortimer. Mortimer was then the real ruler of the country. After this, Edward began to rule on his own.

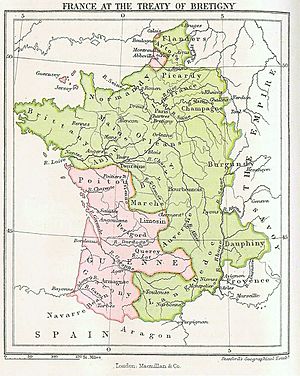

He had success in Scotland. In 1337, he claimed he was the rightful heir to the French throne. This started what became known as the Hundred Years' War. At first, there were some problems. But then, England had great victories at Crécy and Poitiers. These led to the Treaty of Brétigny, which was very good for England. England gained land, and Edward gave up his claim to the French throne. This part of the war is called the Edwardian War. Edward's later years were harder, with military failures and problems at home. This was partly because he was less active and had poor health.

Edward was sometimes quick-tempered but could also be very forgiving. He was a typical king for his time, mostly interested in warfare. People admired him during his life and for centuries after. Modern historians see him as a king who achieved many important things.

Contents

Early Life (1312–1327)

Edward was born at Windsor Castle on 13 November 1312. In his younger years, people often called him Edward of Windsor. His father, Edward II, had a very troubled time as king of England. One big problem was the king's lack of action and repeated failures in the war with Scotland. Another issue was that the king only favored a small group of friends.

When Edward was born in 1312, it helped his father's position against the nobles for a short time. To make the young prince seem even more important, the king made him Earl of Chester when he was only 12 days old.

In 1325, Edward II faced a demand from his brother-in-law, Charles IV of France. Charles wanted Edward II to show loyalty for the English land of Duchy of Aquitaine in France. Edward II did not want to leave England because there were problems at home. These problems were mainly about his close relationship with his favorite, Hugh Despenser the Younger.

Instead, Edward II made his son Edward the Duke of Aquitaine. He sent young Edward to France to show loyalty in his place. Edward went with his mother, Isabella of France. Isabella was King Charles's sister. She was supposed to make a peace treaty with the French. While in France, Isabella secretly planned with Roger Mortimer to remove Edward II from the throne.

To get support for their plan, Isabella arranged for her son to marry 12-year-old Philippa of Hainault. An invasion of England began, and Edward II's soldiers completely left him. Isabella and Mortimer called a parliament. The king was forced to give up his throne to his son. Edward was declared king in London on 25 January 1327. The new king, Edward III, was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 1 February. He was 14 years old.

Early Reign (1327–1337)

Mortimer's Rule and Fall

Soon after Edward became king, new problems arose because Mortimer had too much power at court. Mortimer was now the actual ruler of England. He used his power to gain land and titles. People disliked him more after a humiliating defeat by the Scots at the Battle of Stanhope Park. This led to the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton with the Scots in 1328.

The young king also started to disagree with Mortimer. Mortimer knew his power was not secure and treated Edward disrespectfully. The tension grew after Edward and Philippa married at York Minster on 24 January 1328. They had a son, Edward of Woodstock, on 15 June 1330.

Finally, the king decided to act against Mortimer. With help from his close friend William Montagu and a few other trusted men, Edward surprised Mortimer at Nottingham Castle on 19 October 1330. Mortimer was executed. After this, Edward III began his personal rule.

War in Scotland

Edward III was not happy with the peace agreement made in his name. But the war with Scotland started again because of private actions, not the king's. A group of English nobles, called The Disinherited, had lost land in Scotland due to the peace treaty. They launched an invasion of Scotland. They won a big victory at the Battle of Dupplin Moor in 1332.

They tried to make Edward Balliol king of Scotland instead of the young David II. But Balliol was soon driven out and had to ask Edward III for help. The English king responded by attacking the important border town of Berwick. He defeated a large Scottish army trying to help Berwick at the Battle of Halidon Hill. Edward put Balliol back on the throne and received a lot of land in southern Scotland.

These victories were hard to keep. Soldiers loyal to David II slowly took back control of the country. In 1338, Edward III had to agree to a truce with the Scots. One reason for changing strategy in Scotland was growing worry about England's relationship with France. As long as Scotland and France were allies, England faced fighting on two fronts. The French attacked English coastal towns, leading to rumors of a full French invasion.

Mid-Reign (1337–1360)

The Hundred Years' War Begins

In 1337, Philip VI of France took back the English king's land in Duchy of Aquitaine and the county of Ponthieu. Instead of seeking peace, Edward claimed the French crown. He did this because he was the grandson of Philip IV. The French disagreed, saying that only men could inherit the throne. They supported Philip VI. This disagreement started the Hundred Years' War.

In the early part of the war, Edward tried to make alliances with other European rulers. These alliances did not bring many results. The only big military win in this period was the English naval victory at Sluys on 24 June 1340. This victory gave England control of the English Channel.

Cost of War and Parliament

The high cost of Edward's alliances caused problems at home. The government in England was worried about the growing national debt. The king and his commanders in Europe were angry that England was not sending enough money. To fix this, Edward returned to London without warning on 30 November 1340. He found the government in chaos. He removed many ministers and judges.

These actions did not bring peace at home. A conflict started between the king and John de Stratford, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Stratford claimed Edward had broken the law by arresting royal officers. Some agreement was reached in Parliament in April 1341. Here, Edward had to accept limits on his financial and administrative power in exchange for taxes. However, in October of the same year, the king ignored this agreement.

Crécy and Poitiers

By the early 1340s, it was clear that Edward's alliances were too expensive and not working well. The next years saw more direct involvement by English armies. But these efforts were not successful at first. Edward even failed to repay loans from Italian bankers, which ruined them.

Things changed in July 1346. Edward launched a major attack, sailing to Normandy with 15,000 men. His army attacked the city of Caen. They marched across northern France to meet English forces in Flanders. Edward did not plan to fight the French army at first. But at Crécy, he found good ground and decided to fight the army led by Philip VI.

On 26 August, the English army defeated a much larger French army in the Battle of Crécy. Soon after, on 17 October, an English army defeated and captured King David II of Scotland at the Battle of Neville's Cross. With his northern borders safe, Edward continued his attack on France. He attacked the town of Calais. This was the biggest English effort of the Hundred Years' War, with 35,000 men. The attack started on 4 September 1346 and lasted until the town surrendered on 3 August 1347.

After Calais fell, other events forced Edward to slow down the war. In 1348, the Black Death hit England hard. It killed a third or more of the country's people. This loss of people led to a shortage of farm workers and higher wages. Landowners struggled with fewer workers and rising costs. To control wages, the king and Parliament passed the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349, followed by the Statute of Labourers in 1351. These laws tried to control wages but did not work in the long run. However, they were strongly enforced for a while. Overall, the plague did not cause society to completely break down, and recovery was quite fast. This was thanks to good leaders like Treasurer William Edington.

Large-scale military actions in France did not restart until the mid-1350s. In 1356, Edward's oldest son, Edward, Prince of Wales, won an important victory at the Battle of Poitiers. The English forces, though greatly outnumbered, not only defeated the French but also captured the French king, John II, and his youngest son, Philip.

After these victories, the English held large areas in France. The French king was a prisoner in England, and the French government had almost collapsed. Edward's claim to the French throne now seemed possible. But a campaign in 1359 to finish the job was not successful. So, in 1360, Edward accepted the Treaty of Brétigny. In this treaty, he gave up his claims to the French throne. But he secured his large French lands as fully his own.

Government

New Laws

The middle years of Edward's reign saw many new laws being made. Perhaps the most famous law was the Statute of Labourers of 1351. This law tried to fix the problem of worker shortages caused by the Black Death. The law set wages at their level before the plague. It also tried to stop peasants from moving freely by saying that landowners had the first right to their workers' services. Despite strong efforts to enforce it, the law eventually failed. This was because landowners competed for workers.

Edward III's reign happened during the time when the Pope lived in Avignon, France. This was called the Babylonian Captivity. During the wars with France, people in England opposed what they saw as unfair actions by the Pope. They felt the Pope was too controlled by the French king. People suspected that taxes paid to the English Church were helping to fund England's enemies. Also, the Pope's practice of appointing church officials caused anger.

The statutes of Provisors (1350) and Praemunire (1353) aimed to fix this. They banned papal appointments and limited the power of the Pope's court over English subjects. These laws did not completely break ties between the king and the Pope. They still needed each other.

Another important law was the Treason Act 1351. This law clearly defined the crime of treason. A very important legal change was about the Justices of the Peace. This system started before Edward III. But by 1350, these justices could not only investigate crimes and make arrests. They could also try cases, including serious ones. This created a lasting part of local English justice.

Parliament and Taxes

Parliament was already important by Edward III's time. But his reign was key to its growth. During this period, being a member of the English nobility became limited to those who received a personal invitation to Parliament. This happened as Parliament slowly became a two-part body: the House of Lords and the House of Commons.

The biggest changes happened in the Commons. They gained more political power. A good example is the Good Parliament of 1376. Here, the Commons, with noble support, caused a political crisis for the first time. During this, the process of impeachment and the role of the Speaker were created. Even though these political gains were temporary, this Parliament was a turning point in English political history.

The Commons' political power came from their right to approve taxes. The Hundred Years' War cost a huge amount of money. The king and his ministers tried different ways to pay for it. The king had a steady income from royal lands. He could also get large loans from Italian and English bankers. But to pay for war, he had to tax his people.

Taxes came in two main forms: levies and customs. A levy was a tax on a portion of all movable property. This was usually a tenth for towns and a fifteenth for farmland. This could bring in a lot of money. But each levy had to be approved by Parliament, and the king had to show it was necessary. Customs duties were a good extra income because they were steady and reliable. An "old duty" on wool exports had existed since 1275. From 1336 onwards, new plans were made to increase royal income from wool exports. After some initial problems, it was agreed through the Statute of the Staple of 1353 that new customs should be approved by Parliament. In reality, they became permanent.

Through the steady taxes during Edward III's reign, Parliament, especially the Commons, gained political power. It became clear that for a tax to be fair, the king had to prove it was needed. It had to be approved by the people of the realm, and it had to benefit them. Besides approving taxes, Parliament would also present requests to the king to fix problems, often about royal officials misgoverning. This system helped both sides. Through this process, the Commons became more politically aware. This laid the groundwork for England's unique type of constitutional monarchy.

Chivalry and National Identity

A key part of Edward III's rule was relying on the high nobility for war and government. His father often fought with his nobles. But Edward III successfully created a feeling of friendship between himself and his most important subjects. Edward I and Edward II had limited how many new nobles could be created. Edward III changed this. In 1337, to prepare for the coming war, he created six new earls on the same day.

At the same time, Edward added the new title of duke for close relatives of the king. He also strengthened the sense of community among this group by creating the Order of the Garter, probably in 1348. A plan from 1344 to bring back the Round Table of King Arthur never happened. But the new order had links to this legend because of the garter's circular shape.

This strengthening of the nobility and the growing sense of national identity were linked to the war in France. Just like the war with Scotland, the fear of a French invasion helped create a stronger sense of national unity. It also made the nobility, who had been largely Anglo-Norman since the Norman conquest, feel more English. Since Edward I's time, a popular idea was that the French wanted to destroy the English language. Edward III used this fear to his advantage.

As a result, the English language became much more important. In 1362, a Statute of Pleading ordered English to be used in law courts. The next year, Parliament was opened in English for the first time. At the same time, English became more popular for literature. This was seen in the works of William Langland, John Gower, and especially The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. However, the change to English was not complete right away. The 1362 law was actually written in French and did not have much immediate effect. Parliament was still opened in French as late as 1377. The Order of the Garter, though English, also included foreign members.

Later Years and Death (1360–1377)

While Edward's early reign was active and successful, his later years were marked by less activity, military failures, and political problems. Edward was less interested in daily government than in military campaigns. So, during the 1360s, he relied more and more on his helpers, especially William Wykeham. Wykeham became Keeper of the Privy Seal in 1363 and Chancellor in 1367. But because of his lack of experience, Parliament forced him to resign as chancellor in 1371.

Adding to Edward's problems were the deaths of his most trusted men. Some died from the plague that returned in 1361–62. Their deaths meant that most of the powerful nobles were younger and more loyal to the king's sons than to the king himself.

Edward increasingly relied on his sons to lead military operations. The king's second son, Lionel of Antwerp, tried to control the mostly independent Anglo-Irish lords in Ireland by force. This effort failed. In France, the years after the Treaty of Brétigny were relatively peaceful. But on 8 April 1364, John II died in captivity in England. He was followed by the energetic Charles V, who got help from the skilled Bertrand du Guesclin. In 1369, the French war started again. Edward's son John of Gaunt was given command of a military campaign. This effort failed. By the Treaty of Bruges in 1375, England's large lands in France were reduced to only the coastal towns of Calais, Bordeaux, and Bayonne.

Military failures abroad and the constant cost of campaigns led to political unhappiness at home. These problems came to a head in the Parliament of 1376, known as the Good Parliament. Parliament was called to approve taxes. But the House of Commons used the chance to address specific complaints. They especially criticized some of the king's closest advisors. Lord Chamberlain William Latimer, 4th Baron Latimer and Steward of the Household John Neville were removed from their positions. Edward's mistress, Alice Perrers, who was seen as having too much power over the aging king, was banished from court.

The real opponent of the Commons, supported by powerful men like Wykeham, was John of Gaunt. Both the king and Edward of Woodstock were sick by this time. This left Gaunt in almost complete control of the government. Gaunt was forced to agree to Parliament's demands. But at the next Parliament in 1377, most of the achievements of the Good Parliament were undone.

Edward had little to do with any of this. After about 1375, he played a small role in governing the kingdom. Around 29 September 1376, he became ill with a large infection. After a short recovery in February 1377, the king died of a stroke at Sheen on 21 June.

Succession

Edward III was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, King Richard II. Richard was the son of Edward of Woodstock, who had died on 8 June 1376. In 1376, Edward had signed documents about the order of who would inherit the crown. He listed John of Gaunt, born in 1340, in second place. But he ignored Philippa, who was the daughter of Lionel and born in 1338.

Philippa's exclusion was different from a decision by Edward I in 1290. That decision had recognized that women could inherit the crown and pass it to their children. The order of succession set in 1376 led the House of Lancaster to the throne in 1399. John of Gaunt was the Duke of Lancaster. If Edward I's rule had been followed, Philippa's descendants, including the House of York, would have been favored.

Legacy

Edward III was very popular during his lifetime. Even the problems of his later reign were never blamed directly on him. His contemporary, Jean Froissart, wrote in his Chronicles: "His like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur." This view lasted for a while. But over time, the king's image changed. Later historians criticized Edward for ignoring his duties to his own nation.

Edward has also been accused of giving too much wealth to his younger sons. This might have led to family conflicts that ended in the Wars of the Roses.

From what we know of Edward's personality, he could be impulsive and quick-tempered. This was seen in his actions against Stratford in 1340–41. At the same time, he was known for being very forgiving. Mortimer's grandson was not only forgiven but played an important part in the French wars. He was even made a Knight of the Garter.

In his religious beliefs and interests, Edward was a traditional man. His favorite activity was warfare. In this, he fit the medieval idea of a good king. As a warrior, he was so successful that one modern military historian called him the greatest general in English history. He seems to have been unusually devoted to his wife, Queen Philippa. When Alice Perrers became his lover, the queen was already very ill. This devotion extended to the rest of his family. Unlike many kings before him, Edward never faced opposition from any of his five adult sons.

Family

Edward III had many children with his wife, Queen Philippa.

Sons

- Edward the Black Prince (1330–1376): He was the oldest son and the one expected to become king. He died before his father. He married his cousin Joan of Kent and had a son, who became King Richard II.

- William of Hatfield (1337–1337): Died shortly after birth.

- Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence (1338–1368): The third son. His daughter, Philippa, was an important ancestor for the Yorkist claim to the throne.

- John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (1340–1399): The fourth son. His son, Henry of Bolingbroke, later became King Henry IV.

- Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York (1341–1402): The fifth son. His great-grandson became King Edward IV.

- Thomas of Windsor (1347–1348): Died as a baby from the plague.

- William of Windsor (1348–1348): Died as a baby.

- Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (1355–1397): The eighth son.

Daughters

- Isabella of England (1332–c. 1382): Married Enguerrand VII de Coucy.

- Joan of England (1333/4–1348): She was supposed to marry Peter of Castile but died of the Black Death on her way to Spain.

- Blanche (1342–1342): Died shortly after birth.

- Mary of Waltham (1344–1361): Married John IV, Duke of Brittany.

- Margaret (1346–1361): Married John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke.

Family Connections

Kings of His Time and the Hundred Years' War

Here's how Edward was related to the kings of France, Navarre, and Scotland during his time:

Ancestor to the Wars of the Roses

Edward was also an ancestor of the families involved in the later Wars of the Roses.

| English royal families in the Wars of the Roses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Individuals with red dashed borders are Lancastrians and blue dotted borders are Yorkists. Some changed sides and are represented with a solid thin purple border. Monarchs have a rounded-corner border.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Eduardo III de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Eduardo III de Inglaterra para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |