Parliament of 1327 facts for kids

The Parliament of 1327 was a very important meeting held in London from January to March 1327. This parliament played a key role in changing who was king of England. It led to King Edward II losing his crown and his son, Edward III, becoming king instead.

Edward II was not very popular with the powerful nobles of England. He gave too much power and wealth to his friends, called "favourites," and treated the nobles badly. By 1325, even his wife, Queen Isabella, was unhappy with him. She went to her home country, France, and teamed up with a powerful nobleman named Roger Mortimer. Mortimer had been exiled by Edward II.

In 1326, Isabella and Mortimer invaded England to remove Edward II from power. The King's supporters quickly turned against him. He left London and tried to escape, but he was soon captured and put in prison.

Isabella and Mortimer then called a parliament to make their actions seem legal and proper. The meeting started on January 7, but the King was not there. Edward's 14-year-old son was named "Keeper of the Realm," meaning he was in charge but not yet king. A group from parliament went to Edward II and asked him to come, but he refused.

The parliament continued without him. They accused Edward II of many things, like favoring his friends too much and harming the church. These accusations were called the "Articles of Accusation." The people of London were especially angry with Edward II. Their strong feelings may have helped convince the parliament to agree to remove the King from power. This happened on January 13.

Around January 21, a group of powerful lords went to the King to tell him he was no longer king. They gave him a choice: either he agreed to give the crown to his son, or the lords would choose someone else from outside the royal family. King Edward was sad but agreed. The group returned to London, and Edward III was immediately declared king. He was crowned on February 1, 1327.

After the parliament, Edward II remained in prison and died later that year. Many believed he was killed on Mortimer's orders. Mortimer and Isabella were the real rulers of England, but Mortimer's greed and poor decisions caused more problems. In 1330, Edward III, now older, took control in a coup d'état (a sudden overthrow of the government) against Mortimer and began his own rule.

Contents

Why Edward II Was Unpopular

King Edward II of England had friends like Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger who were very unpopular with the English nobles. Gaveston was killed in an earlier rebellion in 1312, and Despenser was widely hated. Edward was also disliked by ordinary people because he kept asking them to fight in wars against Scotland without pay. None of his military campaigns were successful, which made him even less popular.

In 1322, Edward made things worse by executing his cousin, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, and taking his lands. By 1325, many nobles felt unsafe under Edward's rule. His wife, Isabella of France, also distrusted him, believing Despenser had turned the King against her. In 1324, Queen Isabella was publicly shamed when the government took her lands and dismissed her servants. Historians agree that almost everyone disliked Edward II. Some even called him a "useless king."

France had recently attacked Aquitaine, an English territory. King Edward sent Isabella to Paris, along with their 13-year-old son, Edward, to work out a peace deal. It was said that Isabella promised not to return to England as long as the Despensers were in power. While in Paris, letters between Isabella and Edward, and with her brother King Charles IV of France, showed how much the royal couple had grown apart. By March 1326, this was public knowledge in England, and the King even thought about getting a divorce.

Edward demanded that Isabella and their son return to England, but they refused. Isabella became more open in her criticism of Edward's government, especially against Walter de Stapledon, a close friend of the King and Despenser. King Edward angered his son by taking control of the prince's lands in January 1326. The next month, the King ordered that both Isabella and Edward be arrested if they landed in England.

In Paris, Queen Isabella became the leader of those who opposed King Edward. This group included Mortimer and other powerful nobles who all hated the Despensers. Isabella presented herself and Prince Edward as needing protection from her husband and his court. King Charles of France did not want to support an invasion of England. Instead, the rebels got help from the Count of Hainaut. In return, Isabella agreed that her son would marry the Count's daughter, Philippa of Hainault. This was another insult to Edward II, who had planned to use his son's marriage to make a deal with France, perhaps by marrying him to a Spanish princess.

Invasion of England

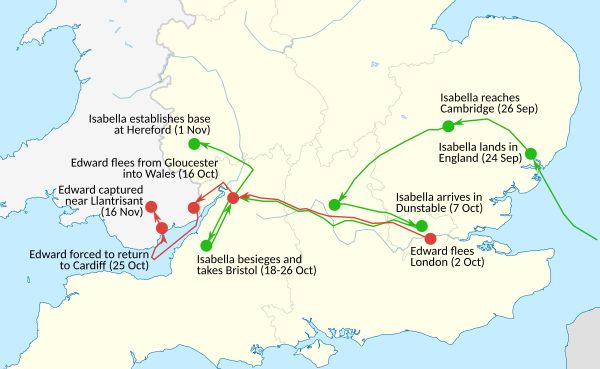

By February 1326, it was clear in England that Isabella and Mortimer planned to invade. Large ships were forbidden from leaving English ports as a defense. King Edward declared war on France in July. Isabella and Mortimer invaded England in September, landing in Suffolk on the 24th. The commander of the royal fleet even helped the rebels, which was one of many betrayals Edward II faced.

Isabella and Mortimer quickly gained strong support among the English leaders. The King's own brother, Thomas, Earl of Norfolk, joined them, along with Henry, Earl of Leicester. Soon after, the Archbishop of Canterbury and several bishops also joined. Within a week, support for the King disappeared. Edward and Despenser left London and fled west. Edward's attempt to gather an army in South Wales failed. He and Despenser were captured on November 16, 1326.

With the King captured, Isabella and Mortimer had to take control. Edward was imprisoned by the Earl of Leicester. People suspected of supporting Despenser or the King were attacked by angry crowds, especially in London.

Isabella spent the end of 1326 in western England. In Bristol, she saw Despenser's father, the Earl of Winchester, face severe punishment. Despenser himself was captured and executed in Hereford within the month. In Bristol, Isabella, Mortimer, and other lords discussed their next steps. On October 26, they declared the young Edward the guardian of the realm. They said this was done "with the agreement of the whole community of the said kingdom." He was not yet officially king.

By November 20, 1326, the Bishop of Hereford had taken the Great Seal (a symbol of royal authority) from the King and given it to his son. This meant Edward III could now be announced as his father's official heir.

Calling the Parliament

Isabella, Mortimer, and the lords arrived in London on January 4, 1327. Parliament met on January 7 to decide what to do now that the King was imprisoned. This parliament had been called by Isabella and the Prince in the King's name back in October. It was supposed to meet in December 1326, but was postponed until January. This was done in the King's name, implying he was abroad, not imprisoned.

Historians have questioned how legal these calls for parliament were. For Isabella and Mortimer, using parliament was a way to solve a big problem and make their power seem legitimate. They needed to make sure the outcome favored them.

People at the time were unsure about the legality of Isabella's parliament. Edward II was still king, even though official papers also mentioned "his most beloved consort Isabella queen of England" and his "firstborn son keeper of the kingdom." Edward II was said to be abroad, but he was actually imprisoned in Kenilworth Castle. It was claimed that he wanted a "conference and consultation" with his lords about the kingdom.

A main goal for the new rulers was to decide Edward II's fate. Mortimer thought about putting him on trial for treason, which could lead to a death sentence. He discussed this with other lords, but they couldn't agree. The lords who were not church officials believed Edward had failed his country so badly that only his death could fix things. However, the bishops argued that because he was anointed by God, he shouldn't be killed. This created a problem for Isabella and Mortimer. A public trial could lead to an unexpected verdict, possibly freeing Edward and putting him back on the throne. They wanted to avoid a trial but keep Edward II imprisoned for life.

Who Attended

This parliament was different from previous ones. Only 26 of the 46 barons who were called in October 1326 were summoned to the January 1327 parliament. The main people who called this parliament were the Bishops of Hereford and Winchester, Roger Mortimer, and Thomas Wake. Isabella was likely working behind the scenes.

Many important people attended, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, bishops, abbots, earls, barons, judges, knights, and town representatives. Knights and town representatives were paid well to attend, which encouraged their support. Sir William Trussell was chosen to speak for the entire parliament, which was a new and important role. There were fewer powerful lords present than usual, which gave more influence to the commoners. This might have been a plan by Isabella and Mortimer, as problems in past parliaments often came from the barons. Some Welsh representatives were called but received their summons too late to attend, or refused out of loyalty to Edward II.

This parliament was a radical gathering. It was more influenced by outsiders and commoners, especially those from London. The rebels deliberately made parliament the central place for their plans.

Parliament in Session

Before parliament officially met, Bishop Adam Orleton and William Trussell were sent to Kenilworth Castle to persuade the King to attend. Edward refused and cursed them. The envoys returned to Westminster on January 12. Historically, parliament could only pass laws with the king present. But after hearing Edward's refusal, his opponents decided not to let his absence stop them. This was the first time parliament continued without the monarch.

A Big Problem for the Government

The different titles given to the young Edward in late 1326 showed a deep problem for the government. The main question was how to transfer the crown between two living kings, which had never happened before. This situation was seen as upsetting the normal order and lacking clear legal rules. People were also unsure if Edward II had given up his throne willingly or was forced to.

On October 26, it was recorded that Edward had "left or abandoned his kingdom." His absence allowed Isabella and Mortimer to rule. They argued that since Edward II had not appointed a regent (someone to rule in his place) while away, his son should govern the kingdom. They also claimed Edward II insulted parliament by calling it a "treasonous assembly." It's not known if the King actually said this, but it helped Isabella and Mortimer. Edward's absence also saved them the embarrassment of having the King present when they removed him from power.

January 12: What Happened

Parliament had to decide its next step. Bishop Orleton asked the lords if they preferred Edward or his son to rule. The response was slow; many were hesitant to remove the King so suddenly. Orleton paused the meeting until the next day. Also on January 12, the Mayor of London and the City Council wrote to the lords, supporting Edward III becoming King and Edward II being removed. They accused Edward II of breaking his coronation oath. Mortimer, who was popular in London, may have encouraged this to influence the lords. The Londoners also suggested that the new king should be guided by his Council until he understood his royal duties. The lords accepted this idea.

January 13: The King is Removed

Whether Edward II resigned or was forced, the crown officially changed hands on January 13, with the support of "all the baronage of the land." Parliament met in the morning, then paused. A large group of lords went to the Guildhall in London, where they swore an oath to support "all that has been decided or will be decided for the common good." This was meant to force those in parliament who disagreed to accept the decision.

The group then returned to Westminster in the afternoon, and the lords formally agreed that Edward II would no longer be King. Several speeches were made. Mortimer announced their decision: Edward II would step down, and "Sir Edward... should govern the realm and be crowned king." A French writer, Jean Le Bel, described how the lords listed Edward II's "ill-advised deeds and actions" to create a legal record. This record stated that "such a man was unfit ever to wear the crown or call himself King." This list of wrongdoings was known as the Articles of Accusation. Bishops gave sermons, with Orleton saying, "a foolish king shall ruin his people."

The Accusations

During the sermons, the official accusations against the King were presented. The King was accused of being unable to rule fairly, listening to bad advisors, preferring his own fun over good government, neglecting England and losing Scotland, harming the church, and breaking his coronation oath. The rebels claimed all these things were well known and undeniable. The accusations blamed Edward's friends for tyranny, but not the King himself, whom they called "beyond hope of reform."

England's military failures in Scotland and France were a big concern for the lords. Edward had not won any successful campaigns, even though he raised huge amounts of money for them. However, blaming Edward II entirely for these losses was not completely fair, as Scotland was already almost lost before he became king.

Edward II is Deposed

Every speaker on January 13 repeated the accusations and offered the young Edward as king if the people approved. The crowd outside, including many Londoners, was very excited. Thomas Wake repeatedly asked the assembly if they agreed with each speaker, crying, "Do you agree? Do the people of the country agree?" His calls, combined with the intimidating crowd, led to shouts of "Let it be done! Let it be done!" This gave the new government some popular support. The Londoners played a key role in making sure that any remaining supporters of Edward II were intimidated.

Edward III was proclaimed king. The day ended with songs and perhaps oaths of loyalty from the lords to the new king. Not everyone agreed; the Bishops of London, Rochester, and Carlisle protested by not participating. The Bishop of Rochester was later attacked by a London crowd for his opposition.

What Happened Next

Edward III's education in ruling was sped up by his advisors. He was still young when he was crowned at Westminster Abbey on February 1, 1327. Real power remained with Mortimer and Isabella. Mortimer was made Earl of March later, but Isabella gained a huge amount of money each year. She asked for her dower (lands and money given to a queen) back, which her husband had taken. It was returned to her with much more added.

After Edward's coronation, parliament was called again. This was unusual, as a new parliament should have been called for a new king. Official records date the entire parliament to Edward III's first year as king, even though it started in his father's reign.

When parliament met again, it returned to its normal work. It heard many requests from the people. These included political requests related to the King's removal, and also requests from the clergy and the City of London. This was the most requests ever submitted by the common people in parliament's history. Their requests ranged from confirming actions against the Despensers to reconfirming the Magna Carta (a famous document limiting the king's power). There were also requests about law and order in local areas. Restoring law and order was a top priority for the new government, as Edward II's failure to do so had been a reason for his removal.

Most of the requests were accepted, leading to seventeen new laws. This showed how eager Isabella and Mortimer were to please the common people. When parliament ended on March 9, 1327, it had been one of the longest parliaments of the century. It was also the only assembly in the late Middle Ages to see a king die and his successor take the throne.

The lands and titles of the dead Earl of Lancaster were given back to his brother Henry. Mortimer's exile was also overturned. The invaders got their lands back in Ireland. To help with the situation in Ireland, parliament pardoned those who had supported Robert the Bruce's invasion. The removed King was only mentioned indirectly in official records, for example, as "Edward his father, when he was king." Isabella and Mortimer tried to prevent the removal from harming their reputations.

The City of London also benefited greatly. In 1321, Edward II had taken away London's rights and removed its mayor. In 1327, Londoners asked parliament for their freedoms to be restored. Since they had been very important in helping the King's removal, on March 7, they received not only their old rights back but even more privileges than before.

Later Events

Meanwhile, Edward II was still imprisoned. Attempts to free him led to him being moved to Berkeley Castle in April 1327. He was moved often to prevent rescue attempts. Edward eventually died at Berkeley on the night of September 21. His death was suspiciously timed, as it removed a rival for Mortimer.

Parliamentary records were usually kept on a "parliament roll." The roll for 1327 is unusual because it does not mention how Edward II stopped being king. It only starts with parliament meeting again under Edward III in February. It is thought that those involved knew the legal basis for Edward's removal was weak, so they might not have recorded it. Another reason could be that Edward III later removed the record himself, so it wouldn't set a bad example of a king being removed.

It wasn't long before Mortimer's relationship with Edward III became difficult. Even though Edward was king, Mortimer was the real ruler. Mortimer's arrogant behavior was clear on the day of Edward III's coronation. He arranged for his three eldest sons to be knighted and even dressed them as earls. Mortimer focused on getting rich and upsetting people. The English army's defeat by the Scots and the peace treaty that followed in 1328 made his position worse.

Edward III, who had initially sided with his mother against his father, did not necessarily like Mortimer. Mortimer was seen as someone whose power went to his head. Edward III married Philippa of Hainault in 1328 and had a son in 1330. Edward decided to remove Mortimer from power. With the help of close friends, Edward launched a surprise attack at Nottingham Castle on October 19, 1330. Mortimer was executed a month later, and Edward III began his personal rule.

How Historians See It

The Parliament of 1327 is important to historians for two main reasons: its role in the development of the English parliament and its part in the removal of Edward II. Some historians see it as a major event in parliament's history, leading to a period of developing new procedures. It also marked a time when the king's power was limited, similar to how it was limited by the Magna Carta. This parliament also saw the first full set of requests from the common people and the first comprehensive law based on such requests.

The second question for scholars is whether Edward II was removed by parliament as an institution, or just while parliament was meeting. While many events happened in parliament, others, like the oath-taking at the Guildhall, happened elsewhere. Parliament was certainly the public place for the removal.

Historians from the Victorian era saw Edward's removal as an early sign of the power of the House of Commons, similar to their own parliamentary system. However, historians today are still divided. Some see it as a removal by the powerful nobles, not by parliament itself. Others call it an abdication, believing Edward II was persuaded to resign. It has been summarized as Edward II being offered "the choice of giving up his throne to his son Edward or being forcibly removed in favor of a new king chosen by his nobles."

Some historians argue that the removal was not revolutionary and did not attack the idea of kingship itself. It was not necessarily illegal, even though it is often described that way. The discussion is also confusing because different people at the time described the meeting in different ways. Ultimately, it was powerful nobles making decisions, with the support of knights and commoners.

Edward's removal also set a precedent (an example for future events) and provided arguments for later removals of kings. For example, the accusations from 1327 were used 60 years later during problems between King Richard II and the Lords Appellant. When Richard refused to attend parliament in 1386, he was reminded that a king who did not attend parliament could be removed, just like Edward II.

It has even been suggested that Richard II might have been responsible for the 1327 parliament roll disappearing when he regained power. Richard saw Edward's removal as a "stain" on the royal family's history. Richard's own removal by Henry Bolingbroke in 1399 naturally drew direct comparisons to Edward's removal. Events from 70 years earlier were seen as "ancient custom" that set a legal example.

Edward II's removal was even used as political propaganda much later, during the last years of King James I in the 1620s.

The Parliament of 1327 was the last parliament before the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 to call Welsh representatives. They never took their seats because South Wales supported Edward, and North Wales opposed Mortimer.

Images for kids

See also

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |