Siege of Calais (1346–1347) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Calais |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crécy campaign during the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

A Medieval depiction of the Siege of Calais |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| England | France | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Edward III | Jean de Vienne | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| • Between 5,000 and 32,000 soldiers at different times • Up to 20,000 Flemish allies • Up to 24,000 sailors in the supporting fleet |

• Garrison size – unknown • Field army – up to 20,000 |

||||||

The Siege of Calais was a major battle that took place from September 1346 to August 1347. It was a key part of the Hundred Years' War, a long conflict between England and France. King Edward III of England led the English army to attack the French town of Calais.

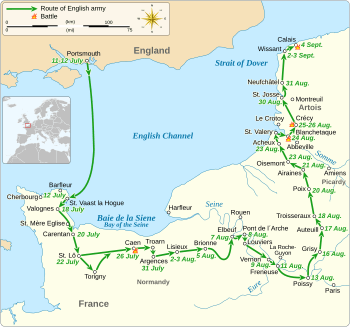

The English army, with about 10,000 soldiers, landed in northern Normandy in July 1346. They went on a huge raid, called a chevauchée (pronounced sheh-vo-SHAY), which means a military ride to destroy enemy lands. They caused a lot of damage across northern France.

On August 26, 1346, the English army won a big victory against a larger French army. This happened at the Battle of Crécy. A week later, the English surrounded the strong port town of Calais. Calais had good defenses and a brave leader named Jean de Vienne.

King Edward tried many times to break through the town's walls or attack it from land or sea, but he failed. During the winter and spring, the French managed to get supplies and more soldiers into Calais by sea. But in April, the English built a fort that blocked the harbor entrance. This stopped any more supplies from reaching the town.

By June 25, Jean de Vienne sent a message to the French King Philip VI, saying they had run out of food. On July 17, King Philip marched north with an army of 15,000 to 20,000 men. But when he saw the strong English and Flemish forces, he decided to retreat. On August 3, Calais finally gave up. This victory gave England an important base in France for the rest of the Hundred Years' War. The French did not get Calais back until 1558.

Contents

Why the War Started

Since 1066, English kings had owned lands in France. This meant they were also vassals (like loyal subjects) to the French kings for those lands. This situation often caused arguments between the two kingdoms. French kings always tried to limit English power and take back lands when they could.

By 1337, England only held Gascony in southwestern France. The people of Gascony preferred being ruled by the distant English king, who left them alone. They did not want to be ruled by the French king, who would interfere more. After many disagreements between Philip VI of France and Edward III of England, King Philip decided to take back Gascony. This decision started the Hundred Years' War, which lasted for 116 years.

The English Invasion of France

Even though the war started over Gascony, King Edward focused his main attacks on northern France. In 1346, he gathered a large army and the biggest fleet England had ever seen, with 747 ships. They landed in Normandy on July 12. The English army had about 10,000 soldiers, including English, Welsh, German, and Breton fighters.

The English surprised the French completely. Edward's goal was to lead a chevauchée to lower the French king's spirits and wealth. His soldiers burned towns and stole everything they could. The English fleet sailed alongside the army, raiding the coast and taking huge amounts of loot. They also captured or burned over 100 French ships.

On July 26, the English attacked and captured Caen, a major city in Normandy. Most of the people were killed, and the city was looted for five days. The English army then marched towards the Seine River on August 1. They destroyed the land all the way to the edges of Rouen and then along the River Seine to Poissy, near Paris.

Duke John of Normandy, King Philip's son, was fighting in Gascony. Philip ordered him to come north to help fight Edward. Meanwhile, the English turned north and found themselves in an area where the French had removed all the food. They escaped by fighting their way across the Somme River against a French blocking force. Two days later, on August 26, 1346, the English won a huge victory at the Battle of Crécy.

The Siege of Calais Begins

After resting for two days, the English army marched north, needing supplies and more soldiers. They continued to destroy towns, including Wissant, a port often used by English ships. Outside Wissant, King Edward decided to capture Calais. Calais was a perfect port for the English, and it was close to their allies in Flanders. The English arrived outside Calais on September 4 and began the siege.

Calais was very well protected. It had two moats, strong city walls, and a citadel with its own moat. The area around it was marshy, making it hard to set up large siege weapons or dig tunnels under the walls. The town had enough soldiers and food, and it was led by the experienced Jean de Vienne. It could also get supplies and help by sea.

The day after the siege started, English ships arrived and brought supplies and more soldiers. The English prepared for a long stay. They built a busy camp to the west, which they called Nouville, or "New Town," with market days twice a week. A huge effort was made to bring food and supplies from all over England and Wales, and also from nearby Flanders. Over the course of the siege, 853 ships and 24,000 sailors were involved, which was a massive undertaking.

The English Parliament, tired of nine years of war, reluctantly agreed to pay for the siege. King Edward said it was a matter of honor and promised to stay until the town fell. Two cardinals from Pope Clement VI tried to arrange peace talks, but neither king would listen to them.

French Problems

King Philip made a mistake: on the day the siege of Calais began, he sent most of his army home to save money. He thought Edward was done with his raid and would go back to England. This allowed English forces in the southwest, led by the Duke of Lancaster, to attack French lands. Lancaster launched a big raid 160 miles north, capturing many towns and castles. These attacks completely messed up the French defenses.

King Philip had also asked the Scots to invade England, as they were allies. The Scottish king, David II, attacked England on October 7. But a smaller English force from northern England defeated the Scots at the Battle of Neville's Cross on October 17. The Scottish king was captured, and most of their leaders were killed or captured. This victory freed up English soldiers to fight in France.

By October, King Philip's army was still small, and he could not pay his soldiers. He canceled all attack plans on October 27 and sent his army home. There was a lot of blame and anger among the French leaders. The King's council argued about who was at fault for the kingdom's problems.

Fighting Continues

During the winter of 1346–47, the English army got smaller, sometimes having as few as 5,000 men. This was because many soldiers' service time ended, Edward wanted to save money, and many soldiers got sick or left. Even with fewer men, Edward tried many times to break the walls of Calais using large machines or cannons. He also tried to attack the town from land or sea, but all his attempts failed.

During the winter, the French worked hard to build up their navy. They used French and Italian ships to bring supplies into Calais without any problems. In March and April, over 1,000 tons of supplies reached the town. King Philip tried to gather his army in late April, but it was still difficult for the French to get their soldiers together quickly.

In April and May, there was some fighting, but nothing was decided. The French tried to cut off the English supply route to Flanders but failed. The English tried to capture other French towns but also failed. In June, the French tried to attack the Flemings, but they were defeated at the Battle of Cassel.

In early 1347, King Edward decided to make his army much bigger. He could do this because the threats from the Scottish army and the French navy were much smaller. For example, he ordered 7,200 archers to join, which was almost as many men as his entire invasion force from the year before.

In late April, the English built a fort at the entrance to Calais harbor. This allowed them to control the harbor and stop any more supplies from reaching the town. In May, June, and July, the French tried to send supply ships through, but they were unsuccessful. On June 25, the leader of Calais sent a message to King Philip, saying they had no food left.

The English kept adding more soldiers to their army throughout 1347, reaching a peak of 32,000 men. This was the largest English army sent overseas before the 1600s. Also, 20,000 Flemish allies gathered near Calais. English ships ran a regular ferry service, bringing supplies, equipment, and more soldiers to the siege.

On July 17, King Philip led the French army north. Edward called his Flemish allies to Calais. On July 27, the French army came within sight of Calais. Their army had between 15,000 and 20,000 soldiers. This was only a third of the size of the English and their allies, who had built strong defenses. The English position was clearly too strong to attack.

To save face, King Philip finally met with the Pope's messengers. They arranged talks, but after four days, nothing was agreed. On August 1, the soldiers in Calais, who had seen the French army nearby for a week, signaled that they were ready to surrender. That night, the French army left. On August 3, 1347, Calais surrendered. The entire French population was forced to leave. The English found a huge amount of valuable goods in the town. King Edward then brought English settlers to live in Calais.

What Happened Next

As soon as Calais surrendered, King Edward sent many of his soldiers home and released his Flemish allies. King Philip also sent his French army home. Edward quickly launched strong raids into French territory. Philip tried to call his army back, but he had serious problems. His treasury was empty, and taxes for the war were hard to collect.

Both sides were tired of fighting and running out of money. The Pope's messengers found that both kings were now willing to talk. Negotiations began on September 4, and by September 28, a truce was agreed. This agreement, called the Truce of Calais, greatly favored the English. It allowed them to keep all the lands they had captured. The truce was supposed to last for nine months but was extended many times until 1355.

The truce did not stop all fighting. There were still naval battles and small fights in other parts of France. Full-scale war started again in 1355 and continued until 1360. The war ended with an English victory and the Treaty of Brétigny. The time from the English landing in Normandy to the fall of Calais became known as Edward III's annus mirabilis (year of marvels).

Calais After the Siege

Calais became very important for England during the rest of the war. It was almost impossible to land a large army in France without a friendly port. Calais also allowed England to gather supplies and equipment before starting a new campaign. The English quickly built many strong forts around Calais to protect it. This area became known as the Pale of Calais.

The town had a very large group of soldiers, about 1,400 men, which was almost a small army. Calais was given many special trading rights, and it became the main port for English goods going to Europe. Calais remained under English control until 1558, when Queen Mary I of England lost it after the 1558 siege. The fall of Calais meant England lost its last possession on mainland France.

Famous Memorial

In 1884, the city of Calais asked a famous artist named Auguste Rodin to create a statue. The statue shows the town leaders at the moment they surrendered to King Edward. This famous artwork, called The Burghers of Calais, was finished in 1889. A writer from that time, Froissart, said that the town leaders expected to be killed. But the English queen, Philippa of Hainault, convinced her husband, King Edward, to show mercy and spare their lives.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |