Crécy campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Crécy campaignChevauchée of Edward III in 1346 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The English assault on Caen, from Froissart's Chronicles |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown, light | Unknown, heavy | ||||||

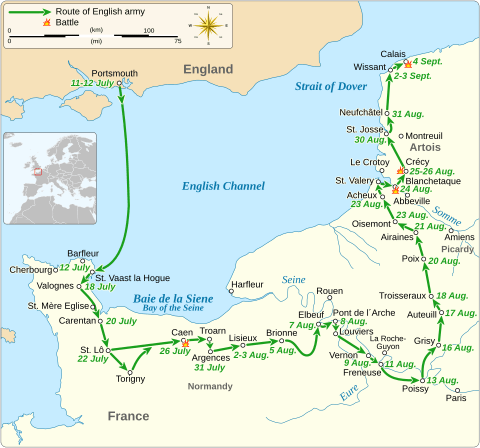

The Crécy campaign was a major military journey by the Kingdom of England across northern France in 1346. This journey, called a chevauchée (pronounced "she-vo-SHAY"), involved large-scale raids that caused a lot of damage. It ended with the famous Battle of Crécy. This campaign was a key part of the long conflict known as the Hundred Years' War.

The campaign started on 12 July 1346, when English soldiers landed in Normandy. It finished when the French city of Calais surrendered on 3 August 1347. King Edward III led the English army. King Philip VI led the French forces.

King Edward III felt pressure from the English Parliament to end the war. He needed to win a big victory or make peace. Edward first thought about landing in Gascony to help the Duke of Lancaster. The Duke was facing the main French army there.

Bad winds changed Edward's plans. He made a surprise landing in northern France instead. The English army then caused widespread damage across Normandy. They attacked and looted Caen, a major city, killing many people.

After Caen, they raided areas near Rouen. Then they marched along the Seine river, getting close to Paris. The French had removed all food from the area, trapping the English. But the English fought their way across a river crossing called Blanchetaque on the Somme river.

Two days later, on 26 August 1346, the English chose a good spot for a battle. They heavily defeated the French at the Battle of Crécy. After this huge win, the English marched to Calais and began a long siege. The siege lasted eleven months and used up many resources from both countries. Finally, Calais fell to the English.

Soon after, a peace agreement called the Truce of Calais was made. It lasted for nine months but was extended many times. Fighting still happened during the truce, but not on the same large scale. Calais became an important English base in northern France for over 200 years.

Contents

Why the War Started

For a long time, English kings also held lands in France. This made them vassals, or loyal subjects, of the French kings. This situation often caused arguments between the two kingdoms. French kings always tried to limit English power and take back these lands.

By 1337, England only held Gascony in the southwest and Ponthieu in the north of France. The people of Gascony liked having a distant English king. He let them manage their own affairs. A French king would likely interfere more.

In 1337, King Philip VI of France decided to take back Gascony and Ponthieu. He said King Edward III of England had not followed his duties as a vassal. This decision officially started the Hundred Years' War, a conflict that would last for 116 years.

Plans for 1345

Even though Gascony was the main reason for the war, Edward had few soldiers to send there. English armies usually fought in northern France. In early 1345, Edward planned to attack France from three directions.

A small group would go to Brittany. A slightly larger force would go to Gascony. The main army would go with Edward to northern France or Flanders. The French knew about these plans. They decided to defend the southwest but focus their main army in the north.

Edward III's main army sailed on 29 June 1345. They stopped in Flanders for a while. Then, a storm scattered their ships, forcing them back to England. After weeks on ships, the soldiers and horses needed to rest. It became too late to start a major attack in northern France that year.

Meanwhile, in Gascony, the English leader, Henry, Earl of Derby, had a great year. He led a quick campaign, winning two big battles. He captured many French towns and forts. This gave the English more control in Gascony. He also captured Aiguillon, a very important town.

Preparing for 1346

In 1346, France still had money problems. They borrowed a lot from the Pope. They also ordered local officials to collect money from everyone. This showed how desperate their finances were. Still, they formed two armies, one at Orléans and one at Toulouse.

Duke John of Normandy, King Philip's son, led all French forces in the southwest. In March 1346, a large French army, with many soldiers and cannons, marched to Aiguillon. They began to besiege it on 1 April. The French focused all their efforts on this attack.

The English leader in Gascony, now known as Lancaster, urgently asked Edward for help. Edward was required to help his loyal subject. His agreement with Lancaster said he would rescue him if he was attacked by too many enemies.

In England, Parliament had approved money for the war in 1344. Much of it was spent, but some was still being collected. English taxpayers could not give much more. Edward also needed money. He took forced loans from church officials and towns. He also took a year's income from foreign church leaders in England.

Huge orders were placed for military gear and food. Many items were bought by force. Normally, Englishmen could be called to fight only to defend their country. In 1346, this rule was changed. They could now be called to serve overseas.

The English people were tired of the war. Parliament had demanded that Edward "make an end to this war, either by battle or by a suitable peace." Edward planned an even larger army for 1346, over 20,000 men.

Edward was worried about the Scots, who were encouraged by Philip to attack England. So, he excused northern counties from sending men to France. He also took steps to protect the English coast from French raids. These actions reduced the number of soldiers available for France.

To get more soldiers, Edward allowed people who had committed crimes to join the army. They would receive a pardon if they served for the whole campaign. About a thousand such men joined. By late June, Edward had about half of his planned army.

The French knew about England's preparations, even though the English tried to keep them secret. It was very hard to land an army without a port. The English no longer had a port in Flanders. They had friendly ports in Brittany and Gascony. So, the French thought Edward would sail to one of those, probably Gascony.

To stop an English landing in northern France, Philip relied on his strong navy. This navy included merchant ships taken for war and hired war galleys. Merchant ships were converted into warships by adding wooden "castles" at the front and back. At least 78 were made into warships in Normandy.

Galleys were fast, oar-powered ships. They were good for raiding and fighting other ships. The French hired at least 32 galleys from Genoa, Italy. They were supposed to arrive by 20 May. But by early July, they were still far away. Some people think the English might have bribed the Genoese to slow them down.

Edward gathered the largest English fleet ever, 747 ships. It was supposed to be ready by 1 March, but this was delayed several times. Edward himself arrived at Porchester on 1 June. He first planned to land in Brittany, but that failed. Then he focused on Gascony, to help Lancaster.

The fleet took on enough supplies for the trip to Bordeaux. It sailed from Portsmouth on 28 June. Not all ships had arrived, so Edward waited near the Isle of Wight. By the time they gathered, the wind was bad. The fleet waited for two weeks, running low on food and water.

After a bad experience the year before, Edward did not want to unload his army and then resupply. He knew that with the French focused on Aiguillon, northern France would be undefended. So, on 11 July, with the wind still blowing the wrong way for the Channel, he changed his mind. He sailed south and landed at St. Vaast la Hogue, near Cherbourg, on 12 July. The Genoese galleys were still far to the south. The French warships had not yet gathered.

Campaign in France

Destroying the Cotentin Peninsula

The English army had between 7,000 and 10,000 soldiers. It included English and Welsh fighters, plus specialists like miners and blacksmiths. It was very well-equipped for a medieval army. Several Norman nobles who disliked French rule also joined.

The landing area, the Cotentin Peninsula, was almost undefended. The English landed easily on the sandy beaches. They spent six days unloading, organizing, and getting supplies. This break helped their horses recover from the long sea journey. The army had a large supply train with weapons, tools, and food. They could get more food from local areas to save their reserves.

Over 50 men were made knights, including Edward's oldest son, as a special ceremony. The local French commander, Robert Bertrand, led 300 local soldiers in a weak attack. He had 500 professional soldiers a few days earlier, but they left because they had not been paid.

The English achieved a complete surprise. They marched south in three groups. Edward's goal was a chevauchée, a large raid. He wanted to lower French morale and take their wealth. Some historians believe Edward also wanted to force the French into a big battle.

Edward gave strict orders not to loot churches, harm civilians, or burn buildings. He set up ways to enforce these rules. However, his soldiers and ship crews were often out of control. Even before leaving the landing site, an abbey near Cherbourg was burned by Englishmen. The towns of Cherbourg, Carentan, Saint-Lô, and Torteval were burned as the army passed. Many smaller places also suffered.

People in some towns were killed. In others, the violence was more random. Most French civilians fled south, filling towns with poor refugees. The English fleet sailed alongside the army, destroying the land up to 5 miles inland. They took huge amounts of loot. Many ships left the fleet once their holds were full. The fleet also captured or burned over 100 French ships. This greatly reduced French raids on English coastal areas.

Bertrand tried to slow the English by destroying bridges. But the English had 40 carpenters who quickly repaired them. French resistance was weak because many Norman fighters were with Duke John at Aiguillon. Raoul, Count of Eu, a top French military leader, was quickly sent north. He decided to defend Caen, a major city in Normandy. Every available man was sent there, and much food was brought in.

When the English arrived on 26 July, Caen was defended by 1,500 soldiers and city guards. The English immediately attacked and captured the city. They looted it for five days. About 5,000 French soldiers and civilians were killed. English losses were small. Raoul of Eu was captured.

The English found a French plan to raid southern England. The Archbishop of Canterbury used this to show that Edward was protecting England. It was also used for years to encourage anti-French feelings.

On 29 July, Edward sent his fleet back to England. He ordered more soldiers, supplies, and money to be sent to meet his army at Le Crotoy, on the Somme river. Money was low; some soldiers had not been paid for months. Edward's direction was clear. Some historians think he already planned to go to Calais. The English marched towards the Seine on 1 August. They left small groups of soldiers in places like Caen, but the French quickly overcame them once the main English army moved on.

Marching Towards Paris

The French army was in a difficult spot. Their main army was stuck besieging Aiguillon. Edward's surprise landing in Normandy was destroying rich French lands. He was showing that he could march wherever he wanted. On 2 August, a small English force invaded France from Flanders. French defenses there were very weak. The French treasury was almost empty.

Philip immediately ordered his main army, led by Duke John, to return from Gascony. But Duke John refused to move until Aiguillon fell. So, the main French army stayed in the southwest.

On 29 July, Philip called for all able-bodied men in northern France to gather at Rouen. Philip arrived there on 31 July. He immediately moved west against Edward with a poorly organized army. Five days later, he returned to Rouen and destroyed the bridge over the Seine behind him.

On 7 August, the English reached the Seine, 12 miles south of Rouen. They raided areas near Rouen. Philip, urged by two cardinals from the Pope, offered peace. Edward replied that he would not waste time with talks and dismissed them. By 12 August, Edward's army was at Poissy, 20 miles from Paris. They had destroyed a 40-mile-wide path along the Seine's left bank, burning villages near Paris.

The people of Paris were very upset. The city was full of refugees. People were preparing to defend the capital street by street. English carpenters built a bridge across the Seine after a group of soldiers secured the other side.

Philip again ordered Duke John of Normandy to leave Aiguillon and march north. On 14 August, Duke John asked for a formal break in the siege. Lancaster, knowing the situation in the north, refused. On 20 August, after over five months, the French gave up the siege and left quickly.

There was confusion in Philip's council. People wondered why he didn't lead the French army to stop the invaders. Instead, Philip sent a challenge on 14 August. He suggested the two armies fight at a chosen time and place. Edward said he would meet Philip south of the Seine, but didn't fully commit. On 16 August, the French moved into position. Edward then burned Poissy, destroyed the bridge, and marched north.

Marching North

The French had removed all food from the area the English were entering. This forced the English to spread out to find food, which slowed them down a lot. Groups of French peasants attacked some smaller English foraging parties.

Philip reached the River Somme a day ahead of Edward. He stayed at Amiens and sent many soldiers to hold every bridge and river crossing between Amiens and the sea. The English were now trapped in an area with no food. The French moved from Amiens and advanced west towards the English. They were ready to fight, knowing they would have the advantage of defending a strong position.

Edward needed to break through the French blockade of the Somme. He tried several points, attacking Hangest and Pont-Remy without success. He then moved west along the river. On the evening of 24 August, the English were camped north of Acheux. The French were 6 miles away at Abbeville.

During the night, the English marched to a tidal river crossing called Blanchetaque. About 3,500 French soldiers defended the other side. English longbowmen and mounted soldiers waded into the river. After a short, fierce fight, they defeated the French.

The main French army had followed the English. Their scouts captured some stragglers and wagons. But Edward had escaped immediate pursuit. The French had been so sure the English could not cross the Somme that they had not removed food from the area. The countryside was rich in food and loot. So, the English were able to get supplies. They looted and then burned Noyelles-sur-Mer and Crotoy, which had large stores of food.

Meanwhile, the Flemish allies had been stopped from crossing a bridge by the French. They then besieged Béthune on 14 August. After some problems, they argued among themselves. They burned their siege equipment and ended their expedition on 24 August. Edward learned he would not get help from the Flemings shortly after crossing the Somme. His fleet was also not waiting with more soldiers at the Somme's mouth.

He decided to fight Philip's army with the soldiers he had. Having shaken off the French chase for a bit, he used the time to prepare a strong defensive position at Crécy-en-Ponthieu. The French returned to Abbeville and stubbornly set off after the English again.

Battle of Crécy

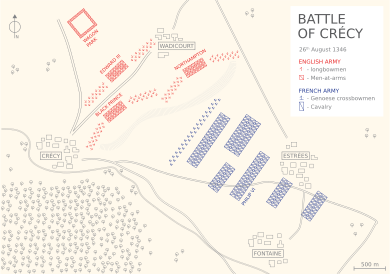

Edward chose a good defensive spot between Crécy and Wadicourt. These towns protected his army's sides. While waiting for the French, the English strengthened their camp. They dug pits in front of their positions and set up some early gunpowder weapons.

Around noon on 26 August, the French advance guard saw the English. At a meeting, senior French leaders were sure they would win. They suggested attacking, but not until the next day. However, the French attacked later that afternoon. It's not clear if Philip planned this, or if too many French knights pushed forward, starting the battle early.

The number of French soldiers is reported differently, but their army was very large for the time. It was several times bigger than the English force. The French unfurled their special battle flag, the oriflamme. This meant no prisoners would be taken.

A large group of Italian crossbowmen went forward to fight the English longbowmen. The English longbows could shoot farther. They also fired more than three times faster. The crossbowmen also lacked their protective shields, which were still with the French supplies. The Italians were quickly defeated and ran away.

The French then sent their mounted knights to charge the English soldiers, who had gotten off their horses to fight. These charges were messy. They had to push through the fleeing Italians. The ground was muddy, and they had to charge uphill. The pits dug by the English also broke up their attacks.

The English archers fired heavily and effectively, causing many deaths. By the time the French charges reached the English foot soldiers, they had lost much of their power. One person at the time described the hand-to-hand combat as "murderous, without pity, cruel, and very horrible." The French charges continued into the night, but with the same result: fierce fighting followed by a French retreat.

Philip himself was caught in the fighting. Two of his horses were killed under him, and he was hit by an arrow in the jaw. The oriflamme was captured after its flag-bearer was killed. The French broke and fled. The English, tired, slept where they had fought.

The next morning, many French soldiers were still arriving. English soldiers, now mounted, charged them. They chased and defeated the French for miles. French losses were very heavy. Records from the time say 1,200 knights were killed and over 15,000 other soldiers. The highest estimate for English deaths was 300.

Modern historians call the English victory "unprecedented" and "a devastating military humiliation." It was a huge political disaster for the French king. The English Parliament was told about the battle on 13 September. They described it in glowing terms, saying it showed God's favor. It also helped justify the high cost of the war.

Siege of Calais

After resting for two days and burying the dead, the English marched north. They needed supplies and more soldiers. They continued to destroy the land, burning several towns. This included Wissant, the usual port for English ships to northern France.

Outside the burning town, Edward held a meeting. They decided to capture Calais. It was a perfect trading post for the English. It was well-defended, had a safe harbor, and was close to England's southern ports. It was also near Flanders, where Edward had allies. The English arrived outside Calais on 4 September and began to besiege it.

Calais was strongly fortified. It was surrounded by large marshes, some with tides. This made it hard to place large siege weapons like trebuchets and cannons. Calais had enough soldiers and food. It could also get more soldiers and supplies by sea.

The day after the siege began, the English ships expected at Crotoy arrived. They brought supplies, equipment, and more soldiers for the English army. The English prepared for a long stay. They built a busy camp to the west, which they called "New Town." It even had two market days each week.

A huge operation brought food from all over England and Wales to supply the besiegers. Supplies also came by land from nearby Flanders. Parliament reluctantly agreed to pay for the siege. Edward declared it a matter of honor and said he would stay until the town fell. Two cardinals from the Pope tried to arrange talks, but neither king would speak to them.

French Problems

Philip kept changing his mind. On the day the siege of Calais began, he sent most of his army home. He thought Edward had finished his raid and would go to Flanders and then home. On or soon after 7 September, Duke John met Philip. Duke John had also recently sent his army home.

On 9 September, Philip announced that the army would gather again at Compiègne on 1 October. This was too short a time. Then they would march to help Calais. This confusion allowed Lancaster in the southwest to attack new areas. He led a raid 160 miles north, capturing many towns and castles. He also attacked the rich city of Poitiers.

These attacks completely messed up French defenses. The fighting moved far from Gascony. Few French soldiers arrived at Compiègne by 1 October. As Philip waited, news of Lancaster's wins arrived. Thinking Lancaster was heading for Paris, the French changed the meeting point for some soldiers to Orléans. They also sent some mustered soldiers there to block Lancaster.

After Lancaster turned south to go back to Gascony, those French soldiers were sent back to Compiègne. French planning fell into chaos.

Philip had been asking the Scots to invade England since June. The Scottish king, David II, believed England's army was all in France. So, he invaded on 7 October. He was met by a smaller English force at Neville's Cross on 17 October. This English force was made only of soldiers from northern England.

The battle ended with the Scots being defeated. Their king was captured, and most of their leaders were killed or captured. This victory freed up many English resources for the war against France. The English border counties could now defend against the Scots on their own.

Even though only 3,000 soldiers gathered at Compiègne, the French treasury could not pay them. Philip canceled all attack plans on 27 October and sent his army home. Everyone blamed each other. Officials in the French treasury were fired. All money matters were given to a committee of three senior abbots. The King's council blamed each other for the kingdom's problems. Philip's son and heir, Duke John, argued with his father. He refused to come to court for several months. Joan II, Queen of Navarre, a French queen, declared she was neutral. She signed a private truce with Lancaster.

Military Actions

From mid-November to late February, Edward tried several times to break the walls of Calais. He used trebuchets and cannons. He also tried to attack the town from land and sea. All attempts failed. During the winter, the French worked hard to build up their navy. This included French and hired Italian galleys, and French merchant ships converted for war.

In March and April, over 1,000 tons of supplies reached Calais by sea without being stopped. Philip tried to gather his army in late April. But the French still struggled to gather their army quickly. By July, it was still not fully ready. Taxes were harder and harder to collect. Several French nobles thought about switching their loyalty to Edward.

Some fighting happened in April and May. The French tried and failed to cut off the English supply route to Flanders. The English tried and failed to capture Saint-Omer and Lille. In June, the French tried to secure their side by attacking the Flemings. This attack was defeated at Cassel.

In late April, the English built a fort at the end of a sand spit north of Calais. This allowed them to control the entrance to the harbor. In May, June, and July, the French tried to send supply ships through, but failed. On 25 June, the commander of the Calais soldiers wrote to Philip. He said their food was gone and they might have to eat each other.

Despite growing money problems, the English steadily sent more soldiers in 1347. Their army reached a peak of 32,000 men. Over 20,000 Flemings gathered less than a day's march from Calais. A total of 853 ships with 24,000 sailors supported this force.

On 17 July, Philip led the French army north. Edward was warned and called the Flemings to Calais. On 27 July, the French army came within sight of the town, 6 miles away. Their army had between 15,000 and 20,000 soldiers. This was a third of the English size. The English had built earthworks and fences to block every approach.

The English position was clearly too strong to attack. Philip finally allowed the Pope's cardinals to meet him. They arranged talks, but after four days, nothing was agreed. On 1 August, the Calais soldiers, who had seen the French army nearby for a week, signaled they were about to surrender. That night, the French army left.

On 3 August 1347, Calais surrendered. All the French people were forced to leave. A huge amount of valuable goods was found in the town. Edward repopulated the town with English people and a few Flemings. Calais became very important for England's war against France. It was almost impossible to land a large army anywhere else without a friendly port. It also allowed England to gather supplies before a campaign.

Strong forts were quickly built around Calais to defend it. This area became known as the Pale of Calais. The town had a very large permanent group of 1,400 soldiers. This was almost a small army. Edward gave Calais many trade benefits. It became the main port for English goods going to Europe, a role it still holds. The time of the chevauchée, from the landing in Normandy to the fall of Calais, was called Edward III's annus mirabilis (year of marvels).

What Happened Next

As soon as Calais surrendered, Edward paid off many of his soldiers. He also released his Flemish allies. Several thousand pardons were given to people who had served in the army. Philip, in turn, sent the French army home.

Edward quickly launched strong raids up to 30 miles into French territory. Philip tried to call his army back, setting a date of 1 September, but faced serious problems. His treasury was empty. Taxes for the war had to be collected by force in many places. Despite these urgent needs, money was not coming in.

The French army did not want to fight anymore. Philip had to threaten to take away the lands of nobles who refused to join. He pushed back the date for his army to gather by a month. Edward also had trouble raising money. He used harsh methods, which were very unpopular.

The English also had two military setbacks. A large raid was defeated by the French soldiers in Saint-Omer. A supply convoy going to Calais was captured by French raiders. The cardinals, acting for the Pope, found willing listeners in September. By the 28th, a truce, called the Truce of Calais, was agreed upon.

This truce was seen as favoring the English most. During the truce, the English kept control of their large land gains in France and Scotland. The Flemings kept their independence. Philip was stopped from punishing French nobles who had worked against him. Edward was so highly respected across Europe after his chevauchée that he was offered the crown of the Holy Roman Empire. Edward declined.

The truce lasted for nine months, until 7 July 1348. But it was extended many times over the years until 1355. The truce did not stop naval fights or fighting in Gascony and Brittany. Full-scale war started again in 1355 and continued until 1360. It ended with the Treaty of Brétigny.

Historian Clifford Rogers says this is when "the English strategy... bore full fruit." Edward gained lands that made up a third of France. He would hold these lands completely, along with a huge ransom for the captured King John. Calais was finally lost by the English queen Mary I in 1558. The fall of Calais marked the loss of England's last possession on mainland France.

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |