Kingdom of Scotland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Scotland

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 843–1707 (1654–1660: Commonwealth) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Motto:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

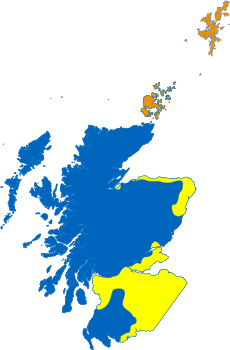

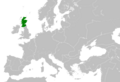

The Kingdom of Scotland in 1190

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Scone (c. 843–1452) Edinburgh (after c. 1452) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Scottish | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 843–858 (first)

|

Kenneth I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1702–1707 (last)

|

Anne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages, Early modern | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• United

|

9th century (traditionally 843) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Lothian and Strathclyde incorporated

|

1124 (confirmed Treaty of York 1237) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Galloway incorporated

|

1234/1235 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1266 (Treaty of Perth) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1472 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 March 1603 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 May 1707 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1482–1707 | 78,778 km2 (30,416 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1500

|

500,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1600

|

800,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1700

|

1,250,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pound Scots | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Scotland was an independent country in northwest Europe. It is believed to have started in 843. Over time, its size changed, but it eventually covered the northern part of the island of Great Britain. It shared a border to the south with the Kingdom of England.

During the Middle Ages, Scotland often fought with England. The most famous conflicts were the Wars of Scottish Independence. In these wars, the Scots fought hard to stay independent from the English. By 1482, after gaining islands from Norway and losing Berwick-upon-Tweed, the Kingdom of Scotland looked much like modern-day Scotland. It was surrounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the southwest.

In 1603, James VI of Scotland also became King of England. This created a "personal union" where one king ruled both countries, but they remained separate kingdoms. Then, in 1707, during the rule of Queen Anne, Scotland and England officially joined together. They formed the Kingdom of Great Britain under the Acts of Union.

The King or Queen (the Crown) was the most important part of Scotland's government. In the Middle Ages, the Scottish monarchs often moved around. Later, Edinburgh became the main capital city in the 15th century. The Crown was central to politics and became a hub for art and culture. However, its direct power lessened after the Union of the Crowns in 1603.

Scotland's government had important roles like the Privy Council. The Parliament also became a key legal body. It oversaw taxes and made policies. In early times, kings relied on powerful lords. But later, they introduced sheriffdoms to gain more direct control. In the 17th century, new local government roles like Justices of Peace helped make things more efficient.

Scots law developed over centuries. It was updated in the 16th and 17th centuries. King David I was the first Scottish king known to make his own coins. After 1603, the Pound Scots was changed to be similar to English money. The Bank of Scotland started printing notes in 1704. Scottish currency was officially stopped in 1707, but Scotland still has its own unique banknotes today.

Scotland is naturally divided into the Highlands and Islands and the Lowlands. The Highlands had short growing seasons, especially during the Little Ice Age. Before the Black Death in 1349, Scotland's population was about 1 million. After the plague, it dropped to half a million. By the 1690s, it grew to about 1.2 million people.

Many languages were spoken in medieval Scotland, including Gaelic, Old English, Norse, and French. By the early modern period, Middle Scots became the most common language. Christianity came to Scotland in the 6th century. In the 16th century, Scotland had a Protestant Reformation. This led to the Church of Scotland, which was mostly Calvinist.

The Scottish Crown had naval forces at different times. But it often used private ships for fighting. Land forces were mainly a large "common army." From the 16th century, Scotland adopted new European military ideas. Many Scots also served as soldiers for other countries.

Contents

History of Scotland

How Scotland Began: 400–943 AD

In the 5th century, northern Britain was split into several small kingdoms. The most important ones were the Picts in the northeast and the Scots of Dál Riata in the west. There were also the Britons of Strathclyde and the Angles of Bernicia (later part of Northumbria).

In 793, fierce Viking raids began. They attacked monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne. This caused fear and confusion. Eventually, the Vikings took over Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Isles.

These threats might have helped the Pictish kingdoms become more like the Gaels. They started using Gaelic language and customs. The Gaelic and Pictish kingdoms also merged. Historians still debate if the Picts took over Dál Riata, or if it was the other way around.

This led to the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s. He became "king of the Picts" (traditionally in 843). His family, the House of Alpin, came to power. When he died in 900, one of his successors, Domnall II (Donald II), was the first to be called rí Alban (King of Alba).

The Latin word Scotia was increasingly used for the heartland of these kings, north of the River Forth. Eventually, the whole area they controlled became known as Scotland. The long rule of Causantín (Constantine II) from 900 to 942/3 is seen as key to forming the Kingdom of Alba/Scotland. He was also credited with bringing Scottish Christianity in line with the Catholic Church.

Growing the Kingdom: 943–1513 AD

Máel Coluim I (Malcolm I) (ruled around 943–954) is thought to have taken over the Kingdom of Strathclyde. The kings of Alba had probably already had some power there since the late 9th century. His successor, Indulf the Aggressor, was called King of Strathclyde before he became King of Alba. He is also credited with taking parts of Lothian, including Edinburgh, from Northumbria.

The rule of David I was a time of big changes. He introduced a system of feudal land ownership. He also set up the first royal burghs (towns) in Scotland. He created the first Scottish coins and continued religious and legal reforms.

Until the 13th century, the border with England changed often. Northumbria was taken by David I but lost by his grandson Malcolm IV in 1157. The Treaty of York (1237) set the borders with England close to where they are today.

By the time of Alexander III, the Scots had taken the rest of the Norwegian-held western coast. This happened after the Battle of Largs and the Treaty of Perth in 1266. The Isle of Man came under English control in the 14th century.

England briefly occupied most of Scotland under Edward I. Later, Edward III supported Edward Balliol to try and reclaim his father's throne. This was part of the Wars of Scottish Independence (1296–1357). The King of France helped Scotland under the Auld Alliance. This alliance meant they would help each other against England.

In the 15th and early 16th centuries, under the Stewart Dynasty, the Crown gained more political control. They also got back most of the lost territory, reaching close to modern Scotland's borders. The Orkney and Shetland Islands became part of Scotland in 1468. This was the last big land gain for the kingdom. In 1482, the border fortress of Berwick fell to the English again. This was the last time it changed hands.

The Auld Alliance with France led to a huge defeat for the Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden Field in 1513. King James IV died in this battle. A long period of political trouble followed.

Coming Together: 1513–1707 AD

In the 16th century, under James V of Scotland and Mary, Queen of Scots, the Crown and court adopted many features of the Renaissance. This happened despite long periods when the kings or queens were too young to rule, civil wars, and interference from England and France.

In the mid-16th century, the Scottish Reformation was heavily influenced by Calvinism. This led to widespread destruction of religious images and the start of a Presbyterian church system. This system had a big impact on Scottish life.

In the late 16th century, James VI became a very influential leader. In 1603, he inherited the thrones of England and Ireland. This created a Union of the Crowns. The three countries kept their own identities and systems. However, the center of royal power moved to London.

When James' son Charles I tried to make Scotland's church more like England's, it led to the Bishops' Wars (1637–1640). The king lost, and Scotland became a mostly independent Presbyterian state. This also helped start the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

After Charles I was defeated, the Scots supported him in the Second English Civil War. After he was executed, they declared his son Charles II king. This led to the Anglo-Scottish War against Oliver Cromwell's republican government in England. Scotland suffered defeats and was briefly made part of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland (1653–1660).

After the monarchy was restored in 1660, Scotland got its separate status back. But political power remained in London. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689, James VII was removed from power. His daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange took the throne. Scotland accepted them under the Claim of Right Act 1689. However, supporters of the old Stuart family, called Jacobites, caused trouble. This led to rebellions, mostly in the Scottish Highlands.

After tough economic times in the 1690s, there were moves to unite politically with England. This union, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain, began on May 1, 1707. The Scottish and English parliaments were replaced by one combined Parliament of Great Britain in Westminster. This new parliament mostly continued English traditions. Forty-five Scots joined the 513 members of the House of Commons. Sixteen Scots joined the 190 members of the House of Lords. It was also a full economic union, changing Scotland's currency, taxes, and trade laws.

How Scotland Was Governed

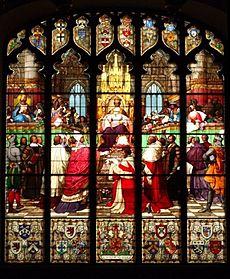

The unified Kingdom of Alba kept some old traditions of Pictish and Scottish kingship. One example was the special coronation ceremony at the Stone of Scone at Scone Abbey.

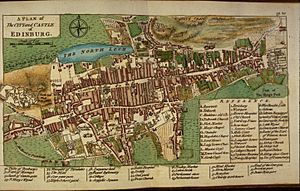

In the Middle Ages, the Scottish king's court often moved around. Scone remained a very important place. Later, royal castles at Stirling and Perth became important. Then, Edinburgh grew to be the capital city in the second half of the 15th century.

The King or Queen (the Crown) was the most important part of the government. This was true even when kings were very young. In the late Middle Ages, the Crown gained more power, like other new monarchies in Europe. Some Scots, like George Buchanan, wrote about ideas of constitutional monarchy (where the king's power is limited). But James VI believed in the divine right of kings, meaning kings got their power from God. These debates continued for many years. The royal court was the center of political life. In the 16th century, it became a big center for art and culture. But it lost much of its power after the Union of the Crowns in 1603.

The Scottish Crown used common government roles, like the Lord Chancellor. The King's Council became a full-time group in the 15th century. It was mostly made up of non-clergy and was very important for justice. The Privy Council, which started in the mid-16th century, and other important state offices, remained central to running the government. This was true even after the Stuart monarchs moved to England in 1603. However, the Privy Council was often ignored and was eventually abolished after the Acts of Union 1707. After that, Scotland was ruled directly from London.

The Parliament of Scotland also became a major legal body. It gained power over taxes and policies. By the end of the Middle Ages, Parliament met almost every year. This was partly because kings were often young, and regents (people who ruled for them) were in charge. This might have stopped the monarchy from making Parliament less important. In the early modern era, Parliament was still vital for running the country. It made laws and approved taxes. But its power changed over time, and it was never as central to national life as the English Parliament.

In early times, Scottish kings relied on powerful lords called mormaers (later earls) and toísechs (later thanes). But from the time of David I, sheriffdoms were introduced. These allowed the king to have more direct control. They slowly limited the power of the big lordships. In the 17th century, the creation of justices of the peace and the Commissioner of Supply helped make local government more effective. Local courts and kirk sessions also helped local lairds (landowners) keep their power.

Scottish Law

Scots law developed into its own unique system in the Middle Ages. It was updated and organized in the 16th and 17th centuries. Before the 11th century, we don't know much about Scots law. It was probably a mix of legal traditions from different cultures living in Scotland, like Celtic, Britonnic, Irish, and Anglo-Saxon customs.

The legal document, the Leges inter Brettos et Scottos, set out a system for paying compensation for injuries and deaths. This was based on a person's rank and their family group. There were also popular courts called comhdhails. In areas held by Scandinavians, Udal law was the basis of the legal system.

When feudalism was introduced during the reign of David I of Scotland, it greatly changed Scottish law. It set up feudal land ownership in many parts of the south and east, which then spread north. Sheriffs, who were first royal administrators and tax collectors, also gained legal duties. Feudal lords also held courts to settle arguments between their tenants.

By the 14th century, some of these feudal courts had become like "petty kingdoms." The King's courts had no power there, except for cases of treason. Burghs (towns) also had their own local laws, mostly about business and trade. Church courts had power over things like marriage, contracts made under oath, inheritance, and legitimacy.

The main law official in the post-Davidian Kingdom of the Scots was the Justiciar. They held courts and reported directly to the king. There were usually two Justiciars, one for Scotia (Gaelic-speaking areas) and one for Lothian (English-speaking areas). Sometimes, Galloway also had its own Justiciar. Scottish common law, called the jus commune, began to form at the end of this period. It combined Gaelic and Britonnic law with practices from Anglo-Norman England and Europe.

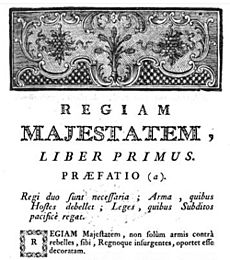

During the time England controlled Scotland, Edward I of England tried to get rid of Scottish laws. Under Robert I in 1318, a parliament at Scone passed a law code based on older practices. It set rules for criminal trials and protected tenants from being removed from their land. From the 14th century, we have early Scottish legal writings, like the Regiam Majestatem (about royal court procedures) and the Quoniam Attachiamenta (about baron's court procedures). These used both common law and Roman law.

Old customs, like the Law of Clan MacDuff, were challenged by the Stewart Dynasty. This led to Scots common law reaching more places. From the reign of King James I, a legal profession started to grow. The handling of criminal and civil justice became more centralized.

Under James IV, the council's legal duties were made clearer. A royal Court of Session met daily in Edinburgh to handle civil cases. In 1532, the Royal College of Justice was founded. This led to the training of professional lawyers. The Court of Session became more independent from influence, even from the king. Its judges could control who joined their ranks. In 1672, the High Court of Justiciary was created as a top court for appeals.

Scottish Money

David I was the first Scottish king known to make his own coins. Soon, there were mints in Edinburgh, Berwick, and Roxburgh. Early Scottish coins looked like English ones. But they had the king's head in profile, not full face. Not many coins were made, so English coins were probably more common. The first gold coin was a noble (worth 6 shillings, 8 pence) from David II.

Under James I, pennies and halfpennies made of billon (a mix of silver and a cheaper metal) were introduced. Copper farthings appeared under James III. During James V's reign, the bawbee (worth 1.5 pence) and half-bawbee were issued. In Mary, Queen of Scots' reign, a two-pence coin called the hardhead was made. This was to help "the common people buy bread, drink, flesh, and fish."

Billon coins stopped being made after 1603. But copper two-pence pieces continued until the Act of Union in 1707. Early Scottish coins had almost the same silver content as English ones. But from around 1300, their silver content started to drop faster than English coins. Between 1300 and 1605, Scottish coins lost silver value three times faster than English coins. The Scottish penny became a base metal coin by about 1484. It almost disappeared as a separate coin from about 1513.

In 1356, an English rule banned lower quality Scottish coins from being used in England. After the union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603, the Pound Scots was changed to match coins of the pound sterling. Twelve Scots pounds were equal to one pound sterling. The Parliament of Scotland decided in 1695 to set up the Bank of Scotland. The bank issued pound notes from 1704, worth 12 Scots pounds. Scottish currency was abolished after the 1707 Act of Union. Scottish coins were collected and re-minted to English standards.

Geography of Scotland

In 1707, the Kingdom of Scotland was half the size of England and Wales. But with its many inlets, islands, and inland lochs (lakes), it had about the same amount of coastline, around 4,000 miles (6,400 km). Scotland has over 790 islands. Most are in four main groups: Shetland, Orkney, and the Hebrides (divided into Inner and Outer). Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 meters (197 feet) above sea level.

The main difference in Scotland's geography is between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west, and the Lowlands in the south and east. The Highlands are further split into the Northwest Highlands and the Grampian Mountains by the Great Glen fault line. The Lowlands are divided into the fertile Central Lowlands and the higher Southern Uplands. The Southern Uplands include the Cheviot Hills, where the border with England ran.

The Central Lowland belt is about 50 miles (80 km) wide. It has most of the good farmland and easier travel. Because of this, it could support most of the towns and government. However, the Southern Uplands and especially the Highlands were less productive and much harder to govern.

Scotland's location on the east Atlantic means it gets a lot of rain. Today, it's about 700 mm (27.5 inches) per year in the east and over 1,000 mm (39 inches) in the west. This helped bogs (wetlands) spread. The acidic soil, strong winds, and salt spray made most islands treeless. Hills, mountains, quicksands, and marshes made travel and conquest very difficult. This might have led to political power being spread out.

The Uplands and Highlands had a short growing season. In the highest Grampians, it was four months or less without ice. For much of the Highlands and Uplands, it was seven months or less. The early modern era also saw the impact of the Little Ice Age. In 1564, there were 33 days of continuous frost, and rivers and lochs froze. This led to several food shortages until the 1690s.

Population Changes

From the start of the Kingdom of Alba in the 10th century until the Black Death arrived in 1349, Scotland's population may have grown from half a million to a million. This is based on how much farmland was available. We don't have exact records of the plague's impact. But there are many stories about abandoned land in the years after. If Scotland was like England, the population might have dropped to as low as half a million by the end of the 15th century.

Compared to later times, like after the Highland Clearances and the Industrial Revolution, these numbers were spread fairly evenly across the kingdom. About half the people lived north of the River Tay. Perhaps ten percent of the population lived in one of the many burghs (towns) that grew in the later medieval period. These were mainly in the east and south. Most towns had about 2,000 people. But many were smaller than 1,000. The largest, Edinburgh, probably had over 10,000 people by the end of the Medieval era.

Rising prices, which usually mean more demand for food, suggest the population probably grew in the first half of the 16th century. It leveled off after the famine of 1595, as prices were stable in the early 17th century. Records from the hearth tax in 1691 show a population of 1,234,575. But this number might have been greatly affected by the famines of the late 1690s. By 1750, including its suburbs, Edinburgh reached 57,000 people. The only other towns with over 10,000 people were Glasgow (32,000), Aberdeen (around 16,000), and Dundee (12,000).

Languages Spoken in Scotland

Old records and place names show how languages changed in Scotland. The Pictish language in the north and Cumbric languages in the south were replaced by Gaelic, Old English, and later Norse in the Early Middle Ages. By the High Middle Ages, most people in Scotland spoke Gaelic. They simply called it Scottish, or in Latin, lingua Scotica.

In the Northern Isles, the Norse language brought by Vikings became Norn. It lasted until the late 18th century. Norse might also have been spoken in the Outer Hebrides until the 16th century. French, Flemish, and especially English became the main languages in Scottish burghs (towns). Most towns were in the south and east. Anglian settlers had already brought a form of Old English to this area.

In the late 12th century, a writer named Adam of Dryburgh described lowland Lothian as "the Land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots." From the time of David I, Gaelic stopped being the main language of the royal court. French probably replaced it. This is shown by old writings and translations of government documents into French.

In the Late Middle Ages, Early Scots, then called English, became the main spoken language of the kingdom. This was true everywhere except the Highlands and Islands and Galloway. Scots came mostly from Old English, with some words from Gaelic and French. Although it was similar to the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late 14th century.

The ruling class started to use Scots as they slowly stopped using French. By the 15th century, Scots was the language of government. Acts of parliament, council records, and treasurer's accounts almost all used it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, which was once common north of the Tay, began to decline. Lowland writers started to see Gaelic as a less important, rural, or even funny language. This helped create a cultural gap between the Highlands and the Lowlands.

From the mid-16th century, written Scots was more and more influenced by the developing Standard English of Southern England. This was due to growing royal and political connections with England. With more English books available, most writing in Scotland started to follow the English style. Unlike many kings before him, James VI generally disliked Gaelic culture. After he became King of England, he preferred the language of southern England. In 1611, the Kirk (Church of Scotland) adopted the 1611 Authorized King James Version of the Bible. In 1617, it was said that interpreters were no longer needed in London because Scots and Englishmen were "not so far different bot ane understandeth ane uther" (not so different that one couldn't understand the other). Historian Jenny Wormald says James created a "three-tier system, with Gaelic at the bottom and English at the top."

Religion in Scotland

The Pictish and Scottish kingdoms that formed Alba were largely converted to Christianity by Irish-Scots missionaries. These missions were linked to figures like St Columba, from the 5th to the 7th centuries. They often founded monasteries and church communities that served large areas. Some scholars believe this led to a unique form of Celtic Christianity. In this form, abbots were more important than bishops. Rules about clerical celibacy (priests not marrying) were more relaxed. There were also some differences in practices compared to Roman Christianity, like how tonsure (haircut for monks) was done and how Easter was calculated. Most of these differences were resolved by the mid-7th century. After Scandinavian Scotland was re-converted from the 10th century, Christianity under the Pope was the main religion.

During the Norman period, the Scottish church went through many changes. With support from the king and nobles, a clearer church structure based on local churches was developed. Many new monasteries, following European styles, became common. The Scottish church became independent from England. It developed a clearer system of dioceses (areas managed by bishops). It became a "special daughter of the see of Rome," but it didn't have archbishops leading it. In the late Middle Ages, problems in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to have more say in who became senior church leaders. Two archbishoprics were set up by the end of the 15th century.

While some historians think monasteries declined in the late Middle Ages, the mendicant orders of friars grew. They were especially popular in growing burghs (towns), meeting the spiritual needs of the people. New saints and ways of showing devotion also became popular. Despite problems with the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the 14th century, and some signs of heresy, the Church in Scotland remained fairly stable before the 16th century.

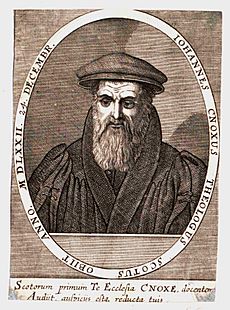

In the 16th century, Scotland had a Protestant Reformation. This created a mostly Calvinist national church (the Kirk). It was strongly Presbyterian, which greatly reduced the power of bishops, though it didn't completely get rid of them. The teachings of Martin Luther and then John Calvin began to influence Scotland. This happened especially through Scottish scholars who had studied in Europe and England. The work of the Lutheran Scot Patrick Hamilton was very important. He and other Protestant preachers were executed in 1528. Zwingli-influenced George Wishart was burned at the stake in St Andrews in 1546. These executions did not stop the spread of Protestant ideas.

Wishart's supporters took over St Andrews Castle. They held it for a year before being defeated with French help. The survivors, including chaplain John Knox, were forced to be galley slaves. This helped create anger towards the French and made martyrs for the Protestant cause. Some tolerance and the influence of Scots Protestants living abroad helped Protestantism grow. A group of nobles declared themselves Lords of the Congregation in 1557. By 1560, a small group of Protestants could bring reform to the Scottish church. In 1560, Parliament adopted a confession of faith, rejecting the Pope's authority and the Mass.

The Calvinism of reformers led by Knox resulted in a Presbyterian system. This system rejected most of the fancy traditions of the Medieval church. This gave a lot of power within the new Kirk to local lairds (landowners). They often controlled who became clergy. This led to widespread, but generally orderly, iconoclasm (destruction of religious images). At this time, most people were probably still Catholic. The Kirk found it hard to reach the Highlands and Islands. But it began a slow process of conversion and strengthening. Compared to other reformations, this one had relatively little persecution.

In 1635, Charles I approved a book of church laws. These laws made him head of the Church, ordered an unpopular ritual, and forced the use of a new prayer book. When the new prayer book came out in 1637, it looked like an English one. This caused anger and widespread riots. Representatives from different parts of Scottish society signed the National Covenant on February 28, 1638. They objected to the King's new church rules. The king's supporters could not stop the rebellion, and the king refused to compromise. In December of that year, things went even further. At a meeting of the General Assembly in Glasgow, the Scottish bishops were officially removed from the Church. The Church was then fully established on a Presbyterian basis. Victory in the resulting Bishops' Wars secured the Presbyterian Kirk. It also helped start the civil wars of the 1640s. Disagreements over supporting the King created a big conflict between different groups in the Kirk.

When the monarchy was restored in 1660, laws passed since 1633 were cancelled. This removed the gains the Covenanters made in the Bishops' Wars. But the church structure of kirk sessions, presbyteries, and synods was brought back. The return of bishops caused particular trouble in the southwest, an area with strong Presbyterian beliefs. Many people there left the official church. They started attending illegal outdoor meetings led by ministers who had been removed, called conventicles. In the early 1680s, a more intense period of persecution began. This was later known as "the Killing Time" by Protestants.

After the Glorious Revolution, Presbyterianism was restored. The bishops, who had generally supported James VII, were abolished. However, William, who was more tolerant than the Kirk, passed acts that restored the Episcopalian clergy who had been removed after the Revolution. This resulted in a Kirk divided into factions. There were also significant minorities of Episcopalians and Catholics, especially in the west and north.

Education in Scotland

When Christianity came to Scotland, Latin became the language for scholars and writing. Monasteries were places of knowledge and education. They often ran schools and taught a small group of educated people. These people were important for creating and reading documents in a society where most people couldn't read.

In the High Middle Ages, new types of schools appeared, like song and grammar schools. These were usually connected to cathedrals or large churches. They were most common in the growing burghs (towns). By the end of the Middle Ages, grammar schools were in all the main burghs and some small towns. There were also "petty schools," more common in rural areas, which gave basic education. Some monasteries, like the Cistercian abbey at Kinloss, welcomed more students. The number and size of these schools seemed to grow quickly from the 1380s.

These schools were almost only for boys. But by the late 15th century, Edinburgh also had schools for girls. These were sometimes called "sewing schools" and were probably taught by women or nuns. Wealthy families also had private tutors for their children. The growing focus on education led to the Education Act 1496. This law said that all sons of nobles and wealthy landowners should go to grammar schools to learn "perfyct Latyne" (perfect Latin). All this led to more people being able to read. But this was mostly among wealthy men. Perhaps 60 percent of the nobility could read by the end of this period.

Until the 15th century, anyone who wanted to go to university had to travel to England or Europe. Just over 1,000 Scots are known to have done this between the 12th century and 1410. The most important scholar among them was John Duns Scotus. He studied at Oxford, Cambridge, and Paris. He probably died in Cologne in 1308. He became a major influence on religious thought in the late Middle Ages.

The Wars of Independence mostly closed English universities to Scots. So, European universities became more important. This changed when the University of St Andrews was founded in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1451, and the University of Aberdeen in 1495. At first, these universities were for training clergy. But more and more non-clergy attended. They began to challenge the clergy's control over government and legal jobs. Those who wanted to study for advanced degrees still had to go abroad.

These international connections helped Scotland join the wider European scholarly world. This was one of the most important ways new ideas of humanism came into Scottish intellectual life.

The Protestant reformers also wanted to expand education. They wanted people to be godly, not just educated. In 1560, the First Book of Discipline proposed a school in every parish. But this was too expensive. In the burghs, the old schools continued. Song schools and new schools became reformed grammar schools or regular parish schools. Schools were supported by church money, local landowners, town councils, and paying parents. Church groups inspected them to check teaching quality and religious beliefs.

There were also many unregulated "adventure schools." These sometimes met local needs or took students away from official schools. Outside of the established town schools, teachers often had other jobs, like minor church roles. At their best, the schools taught catechism, Latin, French, Classical literature, and sports.

In 1616, an act by the Privy Council ordered every parish to set up a school "where convenient means may be had." When the Parliament of Scotland approved this with the Education Act 1633, a tax on local landowners was introduced to pay for it. A loophole that allowed people to avoid this tax was closed in the Education Act 1646. This act created a strong foundation for schools based on Covenanter principles.

Although the Restoration brought back the 1633 rules, new laws in 1696 restored the 1646 provisions. An act of the Scottish parliament in 1696 emphasized the goal of having a school in every parish. In rural areas, this meant local landowners had to provide a schoolhouse and pay a teacher. Ministers and local presbyteries oversaw the quality of education. In many Scottish towns, burgh schools were run by local councils. By the late 17th century, there was a mostly complete network of parish schools in the Lowlands. But in the Highlands, basic education was still missing in many areas.

People generally believed women had limited intellectual ability. But after the Reformation, there was a desire for women to take personal moral responsibility, especially as wives and mothers. In Protestantism, this meant being able to learn the catechism and even read the Bible independently. However, most people, even those who encouraged girls' education, thought they should not get the same academic education as boys.

In lower classes, girls benefited from the growth of parish schools after the Reformation. But they were usually outnumbered by boys. They were often taught separately, for a shorter time, and to a lower level. They were often taught reading, sewing, and knitting, but not writing. Illiteracy rates for female servants were around 90 percent from the late 17th to early 18th centuries. For all women, it was perhaps 85 percent by 1750, compared to 35 percent for men. Among the nobility, there were many educated and cultured women, with Mary, Queen of Scots being a clear example.

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities were reformed by Andrew Melville. He returned from Geneva to become head of the University of Glasgow in 1574. He focused on simpler logic and gave languages and sciences the same importance as philosophy. This allowed old ideas to be questioned. He brought in new specialized teachers. He made Greek compulsory in the first year, followed by Aramaic, Syriac, and Hebrew. This started a new trend for ancient and biblical languages. Glasgow had probably been declining before he arrived, but students now came in large numbers.

Melville helped rebuild Marischal College, Aberdeen. To do for St Andrews what he had done for Glasgow, he was made head of St Mary's College, St Andrews, in 1580. The University of Edinburgh grew from public lectures on law, Greek, Latin, and philosophy in the 1440s. These lectures were supported by Mary of Guise. They became the "Tounis College," which became the University of Edinburgh in 1582. These changes revitalized all Scottish universities. They now offered education as good as anywhere in Europe.

Under the Commonwealth, universities got more funding. They received income from church lands and taxes. This allowed them to complete buildings, like the college in the High Street in Glasgow. They were still mostly seen as training schools for clergy. After the Restoration, there was a purge of the universities. But many of the intellectual advances from before were kept. The universities recovered with a curriculum based on lectures. This curriculum included economics and science. It offered a high-quality education to the sons of nobles and gentry.

Military Forces

Medieval records mention fleets commanded by Scottish kings like William the Lion and Alexander II. Alexander II personally led a large naval force in 1249. It sailed from the Firth of Clyde to Kerrera island. He planned to transport his army to fight the Kingdom of the Isles, but he died before the campaign started. Records show Alexander had several large oared ships built at Ayr. But he avoided a sea battle.

A land defeat at the Battle of Largs and winter storms forced the Norwegian fleet to go home. This left the Scottish Crown as the main power in the region. It led to the Western Isles being given to Alexander in 1266.

Part of Robert I's success in the Wars of Scottish Independence was his ability to use naval forces from the Islands. When the Flemish people were expelled from England in 1303, he gained support from a major naval power in the North Sea. Developing naval power allowed Robert to defeat English attempts to capture him in the Highlands and Islands. He also blockaded major English-controlled fortresses at Perth and Stirling. The Stirling blockade forced Edward II to try to relieve it, which led to the English defeat at Bannockburn in 1314. Scottish naval forces allowed invasions of the Isle of Man in 1313 and 1317, and Ireland in 1315. They were also key in the blockade of Berwick, which fell in 1318.

After Scotland became independent, Robert I focused on building up a Scottish navy. This was mostly on the west coast. Records from 1326 show his vassals in that region had a duty to help him with their ships and crews. Towards the end of his reign, he oversaw the building of at least one royal warship near his palace at Cardross on the River Clyde. In the late 14th century, naval warfare with England was mostly done by hired Scottish, Flemish, and French merchant ships and privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships).

James I showed more interest in naval power. After he returned to Scotland in 1424, he set up a shipbuilding yard at Leith. He also had a house for marine supplies and a workshop. King's ships were built there for both trade and war. One of these ships went with him on his trip to the Islands in 1429. The job of Lord High Admiral probably started around this time. In his fights with his nobles in 1488, James III got help from his two warships, the Flower and the King's Carvel (also known as the Yellow Carvel).

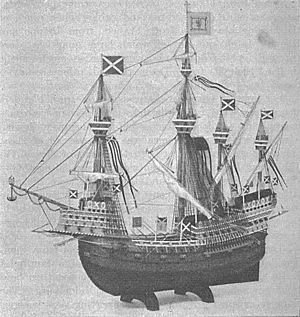

There were several attempts to create royal naval forces in the 15th century. James IV started a new effort. He founded a harbor at Newhaven and a dockyard at the Pools of Airth. He acquired 38 ships, including the Great Michael, which was the largest ship in Europe at the time. Scottish ships had some success against privateers. They went with the king on his trips to the islands and got involved in conflicts in Scandinavia and the Baltic. But they were sold after the Flodden campaign. After 1516, Scottish naval efforts relied on privateer captains and hired merchant ships.

James V did not share his father's interest in building a navy. Shipbuilding fell behind that of the Low Countries. Despite truces between England and Scotland, there were occasional outbreaks of guerre de course (a type of naval warfare using privateers). James V built a new harbor at Burntisland in 1542. The main use of naval power in his reign was a series of trips to the Isles and France.

After the Union of the Crowns in 1603, conflict between Scotland and England ended. But Scotland became involved in England's foreign policy, which exposed Scottish shipping to attack. In 1626, a squadron of three ships was bought and equipped. There were also several marque fleets of privateers. In 1627, the Royal Scots Navy and privateer groups from towns took part in a major expedition to Biscay. The Scots also returned to the West Indies. In 1629, they helped capture Quebec.

During the Bishop's Wars, the king tried to blockade Scotland. He planned attacks from England on the East coast and from Ireland to the West. Scottish privateers captured several English ships. After the Covenanters allied with the English Parliament, they set up two patrol squadrons for the Atlantic and North Sea coasts, called the "Scotch Guard." The Scottish navy could not stand against the English fleet that came with Cromwell's army. Cromwell conquered Scotland in 1649–1651. The Scottish ships and crews were divided among the Commonwealth fleet.

Scottish sailors were protected from being forced into service by English warships. But a set number of conscripts for the Royal Navy were taken from coastal towns in the second half of the 17th century. Royal Navy patrols were now in Scottish waters even in peacetime. In the Second (1665–1667) and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars (1672–1674), between 80 and 120 captains got Scottish letters of marque. Privateers played a big part in the naval conflict. In the 1690s, a small fleet of five ships was set up by merchants for the Darien Scheme. A professional navy was created to protect trade in home waters during the Nine Years' War. Three warships were bought from English shipbuilders in 1696. After the Act of Union in 1707, these ships were transferred to the Royal Navy.

Scottish Army

Before the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the mid-17th century, Scotland did not have a permanent army. In the Early Middle Ages, warfare in Scotland involved small groups of household troops. They often carried out raids and small-scale fighting. By the High Middle Ages, the kings of Scotland could gather tens of thousands of men for short periods. This "common army" was mostly made up of lightly armored spearmen and bowmen.

After the "Davidian Revolution" in the 12th century, which brought some feudalism to Scotland, these forces were joined by a small number of mounted and heavily armored knights. These armies rarely stood up to the usually larger and more professional English armies. But Robert I used them well at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 to secure Scottish independence.

After the Wars of Scottish Independence, the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France played a big part in Scotland's military actions. This was especially true during the Hundred Years' War. In the Late Middle Ages, under the Stewart kings, forces were further increased by specialist troops. These included men-at-arms and archers, hired through special agreements. Archers were highly sought after as mercenaries in French armies in the 15th century. They helped counter the English advantage with bows. They became a major part of the French royal guards as the Garde Écossaise.

The Stewarts also adopted major new ideas in European warfare. These included longer pikes and widespread use of artillery. However, in the early 16th century, one of the best-armed and largest Scottish armies ever gathered was defeated by an English army at the Battle of Flodden Field in 1513. Many ordinary troops, a large part of the nobility, and King James IV himself were killed.

In the 16th century, the Crown took a bigger role in providing military equipment. The pike began to replace the spear. Scots started to switch from bows to gunpowder firearms. The feudal heavy cavalry began to disappear from Scottish armies. The Scots used relatively large numbers of light horsemen, often from the borders. James IV brought in experts from France, Germany, and the Netherlands. He set up a gun foundry in 1511. Gunpowder weapons completely changed how castles were built from the mid-15th century.

In the early 17th century, many Scots served in foreign armies during the Thirty Years' War. As armed conflict with Charles I became likely in the Bishop's Wars, hundreds of Scottish mercenaries returned home. These included experienced leaders like Alexander and David Leslie. These veterans played an important role in training new recruits. These systems formed the basis of the Covenanter armies that fought in the Civil Wars in England and Ireland.

Scottish infantry were generally armed with a mix of pike and shot (muskets), which was common in Western Europe. Scottish armies may also have had individuals with various weapons, including bows, Lochaber axes, and halberds. Most cavalry probably had pistols and swords, though some may have had lances. Royalist armies, like those led by James Graham, Marquis of Montrose (1643–1644) and in Glencairn's rising (1653–1654), were mainly made up of conventionally armed infantry with pike and shot. Montrose's forces lacked heavy artillery for sieges and had only a small cavalry force.

At the Restoration, the Privy Council created several infantry regiments and a few troops of horse. There were also attempts to start a national militia like the English one. The standing army was mainly used to put down Covenanter rebellions and the guerrilla war fought by the Cameronians in the East. Pikemen became less important in the late 17th century. After the socket bayonet was introduced, they disappeared completely. Matchlock muskets were replaced by the more reliable flintlock.

Before the Glorious Revolution, the standing army in Scotland had about 3,000 men in various regiments. There were also a few troops of horse and Horse Guards. Another 268 veterans were in the main garrison towns. After the Glorious Revolution, Scots were drawn into King William II's wars in Europe, starting with the Nine Years' War in Flanders (1689–1697). By the time of the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Scotland had a standing army of seven infantry units, two horse units, and one troop of Horse Guards. It also had varying levels of fortress artillery in the garrison castles of Edinburgh, Dumbarton, and Stirling. These forces were then made part of the British Army.

Flags of Scotland

The earliest record of the Lion Rampant as a royal symbol in Scotland was by Alexander II in 1222. It is shown with an extra embellishment of a double border with lilies during the reign of Alexander III (1249–1286). This symbol was on the shield of the royal coat of arms. A royal banner showing the same symbol was used by the King of Scots until the Union of the Crowns in 1603. Then, it was added to the royal arms and royal banners of later Scottish and British monarchs to represent Scotland. You can still see it today in the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom. Although it's now officially only for use by the Sovereign's representatives and at royal residences, the Royal Standard of Scotland is still one of Scotland's most recognized symbols.

Legend says that Saint Andrew, the patron saint of Scotland, was crucified on an X-shaped cross in Patras. The familiar image of him tied to an X-shaped cross first appeared in Scotland in 1180 during the reign of William I. This image was also on seals used in the late 13th century, including one from 1286 used by the Guardians of Scotland.

The simpler symbol linked to Saint Andrew, the saltire (an X-shaped cross), began in the late 14th century. The Parliament of Scotland decided in 1385 that Scottish soldiers should wear a white Saint Andrew's Cross on their front and back for identification. The first mention of the Saint Andrew's Cross as a flag is in the Vienna Book of Hours, around 1503. It shows a white saltire on a red background. For Scotland, the use of a blue background for the Saint Andrew's Cross is said to date from at least the 15th century. The first clear picture of such a flag is in Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount's Register of Scottish Arms, around 1542.

After the Union of the Crowns in 1603, James VI, King of Scots, ordered new flag designs. These designs combined the flags of the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England. In 1606, a Union Flag was created. It combined the crosses of Saint George (the Flag of England) with that of Saint Andrew. There was also a Scottish version of this flag, where the cross of Saint Andrew was on top of the cross of St George. This design might have been used unofficially in Scotland until 1707. At that time, the English version, where St George's cross was on top of St Andrew's, became the flag of the unified Kingdom of Great Britain.

Images for kids

Related pages

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Escocia para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Escocia para niños