Mary, Queen of Scots facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mary |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Mary c. 1558–1560 at about 17 years old, painted by François Clouet

|

|

| Queen of Scotland | |

| Reign | 14 December 1542 – 24 July 1567 |

| Coronation | 9 September 1543 |

| Predecessor | James V |

| Successor | James VI |

| Regents |

See list

|

| Queen consort of France | |

| Tenure | 10 July 1559 – 5 December 1560 |

| Born | 8 December 1542 Linlithgow Palace, Linlithgow, Scotland |

| Died | 8 February 1587 (aged 44) Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire, England |

| Burial | 30 July 1587 Peterborough Cathedral 28 October 1612 Westminster Abbey |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | James VI and I |

| House | Stuart |

| Father | James V of Scotland |

| Mother | Mary of Guise |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Signature |  |

Mary, Queen of Scots (born 8 December 1542 – died 8 February 1587) was also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland. She was the Queen of Scotland from 1542 until 1567.

Mary became queen when she was only six days old. Her father, James V of Scotland, had died. While she was a child, Scotland was ruled by special guardians called regents. First, James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, was regent. Then, her mother, Mary of Guise, took over.

In 1548, Mary was promised in marriage to Francis, who was the future King of France. She was sent to France to grow up there. This kept her safe from English attacks. Mary married Francis in 1558. She became the queen consort of France when he became king in 1559. Francis died in 1560, and Mary became a widow.

Mary returned to Scotland in 1561. Scotland was facing big changes in religion. Many people were now Protestant, but Mary was Catholic. She tried to rule fairly. She kept Protestant advisors, like her half-brother James Stewart, Earl of Moray.

In 1565, Mary married her cousin, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. They had a son, James, in 1566. In 1567, Darnley died in an explosion. Many people believed James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, was responsible. Bothwell was found not guilty. The next month, he married Mary.

An uprising against Mary and Bothwell followed. Mary was put in prison at Lochleven Castle. In July 1567, she was forced to give up her throne to her one-year-old son. After trying to get her throne back, she escaped to England. She hoped her cousin, Elizabeth I of England, would help her.

Mary was a great-granddaughter of Henry VII of England. Some English Catholics thought Mary should be Queen of England instead of Elizabeth. Elizabeth saw Mary as a threat. She kept Mary imprisoned in different castles for over 18 years. In 1586, Mary was found guilty of planning to harm Elizabeth. She was executed the next year at Fotheringhay Castle.

Contents

Mary's Early Life and Reign

Mary was born on 8 December 1542 at Linlithgow Palace in Scotland. Her parents were King James V of Scotland and Mary of Guise. She was the only one of James's children to live past infancy. Mary became Queen of Scotland six days after her birth. Her father died, perhaps from illness after a battle.

A famous story says that when James heard he had a daughter, he said, "It came with a lass and it will go with a lass!" He meant that the Scottish crown came to his family through a woman. He thought it would be lost through a woman too. This didn't happen with Mary. But it did happen much later with her great-great-granddaughter, Anne, Queen of Great Britain.

Mary was christened at St Michael's Church nearby. An English diplomat saw her in March 1543. He said she was a healthy baby.

Since Mary was a baby, Scotland needed someone to rule for her. This person was called a regent. There were two main people who wanted to be regent. One was the Catholic Cardinal Beaton. The other was the Protestant Earl of Arran. Arran became the regent. But Mary's mother, Mary of Guise, later took over as regent in 1554.

The Treaty of Greenwich

King Henry VIII of England wanted Scotland and England to unite. He suggested that Mary marry his son, Edward. In July 1543, when Mary was six months old, the Treaty of Greenwich was signed. It said Mary would marry Edward at age ten. She would then move to England.

Cardinal Beaton gained power again. He wanted Scotland to stay Catholic and allied with France. This made Henry VIII angry. The Scottish Parliament rejected the treaty in December. This led to Henry's "Rough Wooing". This was a military campaign to force the marriage. English forces attacked Scottish lands.

In 1544, Mary was moved to Dunkeld for safety. She was crowned Queen at Stirling Castle in September 1543. In 1546, Cardinal Beaton was killed. In 1547, the Scots lost a big battle to the English. Mary's guardians sent her to Inchmahome Priory for safety. They asked France for help.

King Henry II of France offered to unite France and Scotland. He suggested Mary marry his three-year-old son, Francis. Mary's guardian agreed to this marriage. In 1548, Mary was moved to Dumbarton Castle. French help arrived in Scotland. In July 1548, the Scottish Parliament agreed to the French marriage.

Life in France

Mary was five years old when she went to France. She spent the next 13 years at the French court. She sailed from Dumbarton in August 1548. She arrived in Brittany, France, a week later.

Mary traveled with her own group of people. This included her two half-brothers. She also had four girls her age, all named Mary. They were called the "four Marys." They were from noble Scottish families.

Mary was lively, beautiful, and smart. Everyone at the French court liked her. She learned to play music and ride horses. She was good at poetry and needlework. She learned French, Italian, Latin, Spanish, and Greek. Her future sister-in-law, Elisabeth of Valois, became a close friend. Mary's grandmother, Antoinette of Bourbon, also had a strong influence on her.

Portraits show Mary had bright auburn hair and hazel-brown eyes. She had smooth, pale skin. She was considered very attractive. She had smallpox as a child, but it didn't leave marks on her face.

Mary was very tall for her time, about 5 feet 11 inches. Francis, her future husband, was shorter and stuttered. But they got along well. In April 1558, Mary secretly agreed to give Scotland and her claim to England to France if she died without children. Twenty days later, she married Francis at Notre-Dame de Paris. He became king consort of Scotland.

Claim to the English Throne

In November 1558, Elizabeth I became Queen of England. Many Catholics thought Elizabeth was not the rightful queen. They believed Mary Stuart was the true queen of England. This was because Mary was a descendant of Henry VII of England. Henry II of France declared Mary and Francis King and Queen of England. This claim to the English throne caused problems between Mary and Elizabeth for many years.

When Henry II died in July 1559, Francis and Mary became King and Queen of France. Mary's uncles, the Duke of Guise and the Cardinal of Lorraine, became very powerful in France.

In Scotland, Protestant leaders were gaining power. Mary's mother, the regent, relied on French soldiers. In 1560, Protestant leaders invited English troops into Scotland. This was to help secure Protestantism. A Protestant uprising in France stopped France from sending more help. Mary's mother died in June 1560. Under the Treaty of Edinburgh, France and England agreed to remove their troops from Scotland. France recognized Elizabeth as Queen of England. But Mary, still in France, refused to agree to the treaty.

Mary Returns to Scotland

King Francis II died in December 1560. Mary was very sad. Her mother-in-law, Catherine de' Medici, became regent for the new French king. Mary returned to Scotland nine months later, in August 1561.

Mary had lived in France since she was five. She didn't know much about the difficult political situation in Scotland. She was a strong Catholic. Many of her subjects were Protestant. The Queen of England also viewed her with suspicion. Scotland was divided between Catholic and Protestant groups. Mary's half-brother, the Earl of Moray, was a Protestant leader.

The Protestant reformer John Knox spoke out against Mary. He criticized her for attending Catholic Mass and dancing. Mary tried to talk to him, but she couldn't change his mind. She later accused him of treason, but he was found not guilty.

Mary surprised many Catholics by accepting the Protestant religion in Scotland. She kept her half-brother Moray as her main advisor. Her council was mostly Protestant. This showed she understood she didn't have strong military power. It also helped her relations with England. She even helped Moray defeat a Catholic leader, Lord Huntly, in 1562.

Mary sent an ambassador to England. He argued that Mary should be the next in line to the English throne. Elizabeth refused to name an heir. She feared it would cause plots against her. But Elizabeth said she knew no one with a better claim than Mary. They planned to meet in England in 1562. But Elizabeth canceled the meeting because of a civil war in France.

Mary then looked for a new husband from Europe's royal families. Her uncle tried to arrange a marriage to Archduke Charles of Austria. Mary was angry because she wasn't asked. She also tried to marry Don Carlos of Spain. But the King of Spain said no. Elizabeth suggested Mary marry an English nobleman, Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. This idea didn't work out.

A French poet at Mary's court, Pierre de Bocosel de Chastelard, was obsessed with Mary. In 1563, he was found hiding under her bed. He was trying to surprise her and declare his love. Mary was very upset and sent him away. But he came back and forced his way into her room. Mary was furious. He was later tried for treason and executed.

Marriage to Lord Darnley

Mary first met her cousin, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, in 1561. Darnley's parents were Scottish nobles who also owned land in England. They hoped their son would marry Mary. Both Mary and Darnley were grandchildren of Margaret Tudor. She was the sister of Henry VIII of England.

Mary and Darnley met again in Scotland in 1565. Mary fell in love with Darnley, who was very tall. They married at Holyrood Palace in July 1565. Both were Catholic. They did not get special permission from the Pope to marry, even though they were cousins.

Elizabeth felt threatened by this marriage. Both Mary and Darnley had claims to the English throne. Any children they had would have an even stronger claim. Mary's decision to marry Darnley seemed to be based on love. The English ambassador said Mary seemed "bewitched." Elizabeth was angry because Darnley was her cousin and an English subject. She felt the marriage needed her permission.

Mary's marriage to a Catholic leader caused her half-brother, the Earl of Moray, to rebel. Other Protestant lords joined him. Mary left Edinburgh in August 1565 to face them. Moray entered Edinburgh but soon left. Mary returned to Edinburgh to gather more troops. Mary and her forces chased the rebellious lords around Scotland. This was called the Chaseabout Raid. Mary's army grew stronger. Moray left Scotland in October and went to England. Mary added more people to her council, including Catholics and Protestants.

Darnley soon became arrogant. He wanted more power. He demanded the Crown Matrimonial. This would have made him co-ruler with Mary. He would also keep the throne if Mary died before him. Mary refused. Their marriage became difficult. They did conceive a child in October 1565. Darnley was jealous of Mary's friendship with her Catholic secretary, David Rizzio.

In March 1566, Darnley joined a secret plot with Protestant lords. On 9 March, these plotters killed Rizzio in front of a pregnant Mary. This happened during a dinner party at Holyrood Palace. Darnley then changed sides. Mary received Moray back at Holyrood. Mary and Darnley escaped the palace. They went to Dunbar Castle for safety. They returned to Edinburgh on 18 March. The rebellious lords were allowed back on the council.

Darnley's Death

Mary's son, James, was born on 19 June 1566. He was born at Edinburgh Castle. But Rizzio's death ruined Mary's marriage. In October 1566, Mary visited the Earl of Bothwell. He was ill from injuries. This visit was later used by Mary's enemies to suggest they were lovers. But no one suspected it at the time. Mary was with her advisors and guards.

After returning, Mary became very ill. She had vomiting, lost her sight and speech, and had fits. People thought she might die. Her French doctors helped her recover. The cause of her illness is not known. It might have been stress or another medical condition.

In November 1566, Mary and her nobles met at Craigmillar Castle. They discussed the "problem of Darnley." They talked about divorce. But it seems they agreed to remove Darnley in another way. Darnley feared for his safety. After his son's baptism, he went to Glasgow. He was ill with a fever for weeks.

In January 1567, Mary asked Darnley to return to Edinburgh. He stayed in a house near the city wall. Mary visited him daily. It looked like they were making up. On the night of 9–10 February 1567, Mary visited Darnley. Then she went to a wedding party. In the early morning, an explosion destroyed Darnley's house. Darnley was found dead in the garden. He seemed to have been smothered. Many people suspected Bothwell. Others suspected Moray, Secretary Maitland, the Earl of Morton, and even Mary herself.

By the end of February, Bothwell was widely believed to have killed Darnley. Darnley's father asked for Bothwell to be tried. Mary agreed. But his request for more time to gather evidence was denied. Bothwell was found not guilty after a short trial in April. A week later, Bothwell convinced many lords to sign a paper. They agreed to support his marriage to the queen.

Mary's Imprisonment and Abdication

Mary visited her son for the last time in April 1567. On her way back to Edinburgh, Lord Bothwell took her to Dunbar Castle. She may have gone willingly or not. On 15 May, Mary and Bothwell married. This was a Protestant ceremony. Bothwell had divorced his first wife just twelve days before.

Mary thought many nobles would support her marriage. But it quickly became very unpopular. Catholics thought the marriage was illegal. Protestants and Catholics were shocked that Mary married the man accused of killing her husband. The marriage was difficult for Mary.

Twenty-six Scottish nobles turned against Mary and Bothwell. They raised an army. Mary and Bothwell faced them at Carberry Hill in June. But Mary's soldiers left her. Bothwell was allowed to leave. The lords took Mary to Edinburgh. Crowds called her a murderer. The next night, she was imprisoned at Loch Leven Castle.

In July, Mary lost twins. On 24 July, she was forced to give up her throne. Her one-year-old son James became king. Moray became regent. Bothwell was forced into exile. He was imprisoned in Denmark and died in 1578.

Escape and Imprisonment in England

On 2 May 1568, Mary escaped from Loch Leven Castle. She was helped by George Douglas. She gathered an army of 6,000 men. But she was defeated by Moray's smaller forces at the Battle of Langside on 13 May. She fled south. After one night, she crossed into England by boat on 16 May. She landed at Workington and stayed at Workington Hall. On 18 May, she was taken into custody at Carlisle Castle.

Mary hoped Elizabeth would help her get her throne back. But Elizabeth was careful. She ordered an investigation into Mary's actions. In July 1568, Mary was moved to Bolton Castle. This was farther from Scotland. An inquiry was held in York and Westminster. In Scotland, Mary's supporters fought a civil war against Regent Moray.

The Casket Letters

Mary refused to accept that any court could try her. She was a queen. She did not attend the inquiry herself. She sent representatives. Elizabeth also forbade her from attending. As evidence against Mary, Moray presented the "casket letters." These were eight unsigned letters. They were supposedly from Mary to Bothwell. There were also two marriage contracts and a love poem. They were said to be found in a silver box. Mary said she didn't write them. She said they were fakes. She argued her handwriting was easy to copy.

Historians still debate if the casket letters were real. The original French letters might have been destroyed in 1584. The copies that exist are not complete. Some historians believe they were fakes. Others think parts were added to real letters. Some phrases in the letters are similar to Mary's known writings. But the French grammar is poor for someone with Mary's education.

The casket letters were not shown publicly until 1568. Mary had been forced to give up her throne and was held prisoner for almost a year. The letters were not used then to justify her imprisonment. Some historians think this means the letters contained real evidence. Others think it means the lords needed time to make them up. Some people at the time who saw the letters believed they were real.

Most of the people at the inquiry accepted the letters as real. They compared the handwriting to Mary's. Elizabeth did not officially say Mary was guilty or innocent. She had political reasons for this. Moray returned to Scotland as regent. Mary remained a prisoner in England. Elizabeth had kept a Protestant government in Scotland. She did this without condemning or releasing Mary.

Plots Against Elizabeth

In January 1569, Mary was moved to Tutbury Castle. She was placed under the care of the Earl of Shrewsbury and his wife Bess of Hardwick. Elizabeth saw Mary as a serious threat to her throne. So she kept Mary in various castles far from the coast.

Mary was allowed to have her own staff. She needed many carts to move her belongings. Her rooms were decorated with beautiful tapestries. She had her own chefs. She was sometimes allowed outside under strict watch. She spent time doing embroidery. Her health got worse. She had severe rheumatism and became lame.

In May 1569, Elizabeth tried to help Mary get her throne back. But Scottish leaders rejected the idea. The Duke of Norfolk continued to plan to marry Mary. Elizabeth put him in the Tower of London. In 1571, Elizabeth's advisors uncovered the Ridolfi Plot. This was a plan to replace Elizabeth with Mary using Spanish soldiers. Norfolk was executed. The English Parliament tried to pass a law to remove Mary from the throne. But Elizabeth refused to sign it. Plots around Mary continued.

Mary sent secret letters to the French ambassador. Many of these letters were found and decoded later. After another plot in 1583, a law was passed. It said anyone who plotted against Elizabeth could be killed. It also aimed to stop any successor from gaining from Elizabeth's death.

In 1584, Mary suggested an "association" with her son, James. She offered to stay in England and give up her claim to the English crown. She also offered to join an alliance against France. But James eventually rejected this idea. He signed an alliance with Elizabeth instead. Elizabeth also rejected Mary's offer. She didn't trust Mary to stop plotting.

In 1585, a man named William Parry was found guilty of plotting to kill Elizabeth. Mary was not aware of this plot. But her agent was involved. Mary was then placed under stricter guard. She was moved to a manor house at Chartley.

Mary's Trial

On 11 August 1586, Mary was arrested. She was accused of being involved in the Babington Plot. This was a plan to kill Elizabeth. Elizabeth's advisor had set a trap for Mary. Mary's letters were secretly sent out of Chartley. Mary thought they were safe. But they were decoded and read. These letters showed Mary had approved the plan to kill Elizabeth.

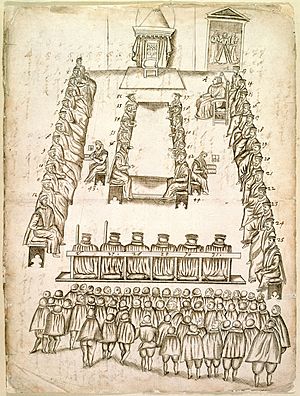

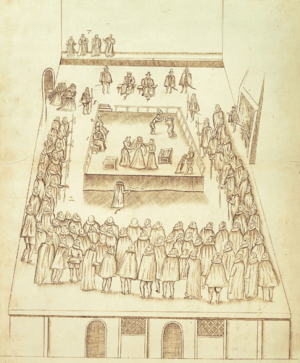

Mary was moved to Fotheringhay Castle. In October, she was put on trial for treason. A court of 36 noblemen heard the case. Mary strongly denied the charges. She said she had not been allowed to see the evidence. She said her papers were taken. She also said she was a foreign queen, not an English subject. So she could not be guilty of treason against England.

Mary was found guilty on 25 October. She was sentenced to death. But Elizabeth hesitated to order her execution. She worried that killing a queen would set a bad example. She also feared Mary's son, James, might invade England.

Elizabeth asked Mary's guard to secretly end Mary's life. But he refused. On 1 February 1587, Elizabeth signed the death warrant. Ten members of her council decided to carry out the sentence at once. They did this without Elizabeth's direct knowledge.

Execution and Burial

On the evening of 7 February 1587, Mary was told she would be executed the next morning. She spent her last hours praying. She gave her belongings to her staff. She also wrote her will and a letter to the King of France.

When Elizabeth heard about the execution, she was very angry. She said her advisor had disobeyed her. She said her council acted without her permission. This allowed her to deny direct responsibility for Mary's death. The advisor was arrested and imprisoned. He was released later.

Mary had asked to be buried in France. But Elizabeth refused. Mary's body was prepared and placed in a lead coffin. She was buried in a Protestant service at Peterborough Cathedral in July 1587. In 1612, Mary's son, King James VI and I, ordered her body to be moved. She was reburied in Westminster Abbey. Her tomb is opposite Elizabeth's. Many of her descendants are also buried in her vault.

See also

In Spanish: María I de Escocia para niños

In Spanish: María I de Escocia para niños