Francis II of France facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Francis II |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by François Clouet

|

|

| King of France (more...) | |

| Reign | 10 July 1559 – 5 December 1560 |

| Coronation | 21 September 1559 |

| Predecessor | Henry II |

| Successor | Charles IX |

| King consort of Scotland | |

| Tenure | 24 April 1558 – 5 December 1560 |

| Born | 19 January 1544 Château de Fontainebleau, France |

| Died | 5 December 1560 (aged 16) Hôtel Groslot, Orléans, France |

| Burial | 23 December 1560 Basilica of St Denis, France |

| Spouse | |

| House | Valois-Angoulême |

| Father | Henry II of France |

| Mother | Catherine de' Medici |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

Francis II (French: François II; 19 January 1544 – 5 December 1560) was the King of France from 1559 to 1560. He was also King consort of Scotland. He gained this title when he married Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1558.

Francis became king of France at age 15. This happened after his father, King Henry II, died in an accident in 1559. His short time as king was marked by the start of the French Wars of Religion. These were big conflicts between Catholics and Protestants in France.

Even though Francis was old enough to rule (the legal age was 14), his mother, Catherine de' Medici, let others help him. She gave control of the government to his wife Mary's uncles. These were members of the House of Guise, who strongly supported the Catholic faith. They tried to help Catholics in Scotland but could not stop the Scottish Reformation. This led to the end of the Auld Alliance, a long friendship between France and Scotland.

After Francis, two of his younger brothers became king. They also struggled to ease the tensions between Protestants and Catholics.

Contents

Early Life and Education (1544–1559)

Francis was born on January 19, 1544. He was the first son of King Henry II and Catherine de' Medici. He was born 11 years after his parents got married. Francis grew up at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. He was baptized on February 10, 1544, in Fontainebleau. His godparents included King Francis I and Pope Paul III.

In 1546, he became the governor of Languedoc. In 1547, when his grandfather Francis I died, he became the Dauphin of France. This meant he was the heir to the French throne.

Francis had teachers who taught him many things. Jean d'Humières and Françoise d'Humières were his guardians. Pierre Danès, a Greek expert, was his tutor. He also learned dancing and fencing.

A Royal Marriage

When Francis was only four years old, his father, King Henry II, arranged for him to marry Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary was just five years old at the time. This agreement was made on January 27, 1548. Mary had become Queen of Scotland when she was only nine months old. This was after her father, King James V, died.

Mary was the granddaughter of Claude, Duke of Guise. He was a very important person at the French court. After the marriage plan was set, Mary came to France to be raised at the royal court. She was tall and spoke well for her age. Francis was shorter and had a stutter. But King Henry II said they got along very well from the start.

On April 24, 1558, Francis and Mary were married at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. This marriage was very important. It could have given future French kings a claim to the throne of Scotland. It also gave them a claim to the throne of England. This was through Mary's great-grandfather, King Henry VII of England. Because of this marriage, Francis became the king consort of Scotland.

Becoming King of France

Just over a year after his wedding, Francis became king. This happened on July 10, 1559. He was 15 years old when his father, King Henry II, died from a jousting accident.

On September 21, 1559, Francis II was crowned king in Reims. His uncle, Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine, performed the ceremony. The crown was so heavy that nobles had to help hold it on his head. After the coronation, the court moved to the Loire Valley. The Château de Blois became the new king's home. Francis II chose the sun as his symbol. His mottos were Spectanda fides (This is how faith should be respected) and Lumen rectis (Light for the righteous).

By French law, Francis was old enough to rule without a regent. But he was young, had little experience, and was not very strong. So, he gave his power to his wife's uncles. These were Francis, Duke of Guise, and Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine. His mother, Catherine de' Medici, agreed to this. On his first day as king, Francis II told his ministers to take orders from his mother. But she was still sad about her husband's death, so she sent them to the Guise family.

The two older Guise brothers were already important during Henry II's reign. Francis, Duke of Guise, was a famous military leader. Cardinal Charles had been part of major talks and kingdom matters. When Francis II became king, the brothers split their duties. Duke Francis led the army, and Charles managed money, justice, and foreign relations.

The rise of the Guise family meant less power for their rival, Anne de Montmorency. He was a high-ranking officer called the Constable of France. The new king suggested he leave court to rest. Diane de Poitiers, the previous king's mistress, was also asked to stay away from court. This was a big change in who held power.

Francis II's Reign (1559–1560)

Challenges at Home

France's Situation

When Henry II died, France was almost bankrupt. The country owed a lot of money, about 40 million livres. Lenders were worried because the crown often struggled to pay its debts. Henry's religious policies had also failed. His strict laws against Protestants did not stop the growth of Calvinism in France. Religious violence was increasing in cities like Paris.

The Guise Family Takes Charge

The Guise family faced problems from the start. Other noble families, like the Montmorency and Bourbon families, did not like their new power. The Guises tried to fix the country's money problems. They cut down the army's size and delayed payments to soldiers. This made the soldiers angry. They also had to ask provinces for forced loans to cover the money shortages.

In terms of religion, the Guises first continued to punish Protestants. From July 1559 to February 1560, they passed more laws against them. These laws included tearing down houses where Protestants met. Landlords who knew they had Protestant tenants could also be punished.

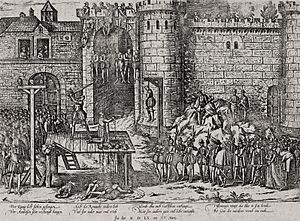

The Amboise Conspiracy

Some people were unhappy with the Guise family's rule. Protestants and military men from less noble families joined together. They formed a plan to capture the king and arrest or kill the Guise brothers. This plot was led by a man named La Renaudie. They wanted Antoine of Navarre to lead them as a "regent" for Francis II. When he wasn't interested, they turned to his brother Condé, who was more open to the idea.

News of the plot began to spread. On February 12, a lawyer who had changed his mind told the Guise family and Francis everything. They learned the leader's name was La Renaudie. With this information, the Guises called many nobles to Amboise and made the castle stronger.

In March, the court acted. They arrested some plotters who were meeting to get money for the plan. Days later, a larger group of soldiers tried to attack Amboise but were pushed back. On March 17, Francis II made the Duke of Guise the main military leader of the kingdom. The court realized the plot involved different kinds of people. So, on March 17, they offered forgiveness to those who put down their weapons within 48 hours.

The court then had to decide what to do with those they captured. They tried to find proof that Condé was involved. Condé denied the accusations. The Queen Mother told him no one doubted him. But on April 18, his rooms were searched. Since no proof was found, he was allowed to leave court. Condé quickly went south to join his brother Antoine.

The military plotters who kept fighting were not shown mercy. Many were executed. This included men from good families, which shocked some at court. However, the court realized its religious policy was failing. On March 8, the Edict of Amboise was issued. It offered forgiveness for those found guilty of heresy, as long as they lived as good Catholics. This law started to separate the crime of heresy from the crime of rebellion.

Problems in the Provinces

Even though the rebellion at Amboise was stopped, problems grew in other parts of France. Groups of soldiers who were part of the plot were left without leaders. They caused trouble in their local areas. Many Protestants also started taking over churches and destroying religious images. This happened in cities like Rouen. By summer, this rebellious movement became stronger. Several cities in southern France were in revolt.

The worst of this disorder came in early autumn. On September 4, in Lyon, authorities found a large amount of weapons. After a short fight with Protestants, the weapons were seized. This stopped a planned takeover of the city. This close call made the king and his government even angrier. They suspected Condé was involved. This was confirmed when one of his agents was caught with papers that showed his guilt.

The king reacted strongly. He sent his army to the rebellious areas to stop the unrest. He also ordered governors to return to their posts. To further isolate the rebellious princes, the government created two new super-governorships. They gave these to Charles, Prince of La Roche-sur-Yon and Louis, Duke of Montpensier. This separated their interests from their cousins. Condé and Navarre were greatly outnumbered. They decided it was pointless to fight. They left their power base in the south and agreed to attend the upcoming Estates General.

New Religious Policies

The government started a new religious policy. It separated heresy (religious belief) from sedition (rebellion). While Protestant worship was not allowed, the goal was to avoid bloodshed and unite the kingdom. This change in policy was helped when Michel de l'Hôpital became the Lord Chancellor of France in April. Hôpital was a Catholic who did not like the harsh punishments of the 1550s. With Cardinal Charles of Lorraine, Catherine de Medici, and Admiral Coligny, he pushed for this new religious approach.

In May 1560, another law was passed, the Edict of Romorantin. This law spoke against the spread of heresy. But it also admitted that the old policies had failed. The law said that trials for heresy would now be handled by church courts. These courts could not give death sentences. This meant that the death penalty for heresy was mostly ended. For more serious acts, like rebellious preaching, other courts would handle the cases.

The Guise family knew that France still had money and religious problems. They decided to call an Assembly of Notables. Condé and Navarre were not among the nobles who attended, as they feared arrest. Cardinal Lorraine wanted the assembly to agree to a national religious meeting to unite the two faiths peacefully. However, Admiral Coligny changed the plan. He asked for Protestants in Normandy to be allowed to build their own churches. The Duke of Guise was very angry about this. The assembly suggested new tax ideas. It ended by calling the Estates General to discuss these ideas. It was first planned for Meaux, but then moved to Orléans due to religious issues.

The Pope decided to reopen the general council of Trent. He did not want any Protestants to attend. This was against the French crown's wish to have their own national council.

The Estates General was a chance to bring Condé under control. In October, he was told to come to the meeting. When he arrived, he and some friends were arrested and put on trial. Condé was found guilty and likely imprisoned.

Foreign Policy

Francis II continued the peace efforts his father, Henry II, had started. The Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, signed in April 1559, ended 40 years of war between France and the Habsburg empire. France gave back lands it had won over the past 40 years. This meant that Francis II's reign began a time when France's power in Europe started to lessen. Spain became more powerful.

When Henry II died, France was already giving back these lands. Francis II knew France was weak. He told Spain that France would keep its promise to follow the treaty. By autumn 1559, France had left most of Savoy and Piedmont. There were only five places left that were agreed upon in the treaty.

France also had to talk about, pay, or ask for money for people whose property was taken or destroyed during the war. They also had to agree with Spain about war prisoners. Many nobles were still prisoners and could not pay to be freed. Common soldiers were forced to work as rowers on royal ships. Even after a deal was made to release prisoners, Spain did not want to let go of theirs.

By the time Francis II died, France had pulled its troops out of Scotland, Brazil, Corsica, Tuscany, Savoy, and most of Piedmont.

Losing Scotland

Because Francis II married Mary Stuart, Scotland's future was tied to France. A secret part of their marriage agreement said that Scotland would become part of France if they had no children. Mary's mother, Marie of Guise, was already ruling Scotland for her daughter.

Because France controlled Scotland, a group of Scottish lords started an uprising. They made the regent and her French helpers leave Edinburgh in May 1559. Marie of Guise asked France for help. Francis II and Mary Stuart quickly sent troops. By the end of 1559, France had control of Scotland again.

Only England's support for the Scottish nobles seemed to stand in the way of French control. Queen Elizabeth I of England was angry. Francis II and Mary Stuart had put England's coat of arms on their own. This showed Mary's claim to the English throne. In January 1560, the English fleet blocked the port of Leith. French troops had made it a military base. In April, 6,000 English soldiers and 3,000 horsemen arrived. They began to surround the city.

The English troops were not very successful. The French troops were in a better position. But France's poor financial situation and problems at home meant no more soldiers could be sent. When French negotiators arrived in Scotland, they were treated almost like prisoners. Marie of Guise was trapped in an Edinburgh fortress. The two men had to agree to a peace deal that was bad for France.

On July 6, 1560, they signed the Treaty of Edinburgh. This ended French control of Scotland. Francis II and Mary Stuart had to take French troops out of Scotland. They also had to stop using England's coat of arms. A few weeks later, Scotland's parliament made Protestantism the official religion. When Francis II and Mary Stuart saw the Treaty of Edinburgh, they were very angry. They refused to sign it and said the Scottish parliament's decision was not valid.

Death of the King

The king's health got worse in November 1560. On November 16, he fainted. After only 17 months as king, Francis II died on December 5, 1560. He died in Orléans, France, from an ear infection. Doctors have suggested it could have been mastoiditis, meningitis, or an ear infection that led to an abscess. Some people thought Protestants had poisoned the king. This idea was popular among Catholics because religious tensions were high. However, this has never been proven.

Francis II died without having any children. So, his younger brother, Charles, who was ten years old, became the next king. On December 21, the royal council named Catherine de' Medici, Francis's mother, as the Regent of France. The Guise family left the court. Mary Stuart, Francis II's widow, returned to Scotland. Louis, Prince of Condé, who was in jail and waiting to be executed, was freed after talks with Catherine de Médici.

On December 23, 1560, Francis II's body was buried in the Basilica of St Denis.

Legacy

Francis II had a very short time as king. He became king as a young teenager. This was a time when France was facing big religious problems. Historians agree that Francis II was not very strong, both physically and mentally. His weak health led to his early death.

Titles and Symbols

- King of France (1559–1560)

- King consort of Scotland (1558–1560)

- Duke of Brittany (1544)

- Dauphin of Viennois (1547)

-

Royal arms of Francis, Dauphin and King consort of Scots

-

Royal arms of Mary, Queen of Scots, Queen consort of France

-

Royal arms of Mary, Queen of Scots, Queen dowager of France

Portrayals in Media

Francis II has been shown in several TV shows and movies:

- Toby Regbo plays him in the TV show Reign.

- Richard Denning plays him in the 1971 film Mary, Queen of Scots (1971 film).

- Sebastian Stragiotti-Axanciuc plays him in the 2013 film Mary, Queen of Scots (2013 film).

- George Jaques plays him in The Serpent Queen.

See also

In Spanish: Francisco II de Francia para niños

In Spanish: Francisco II de Francia para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |