Michel de l'Hôpital facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michel de l'Hôpital

|

|

|---|---|

| Chancellor of France | |

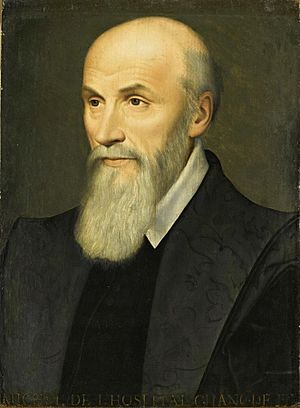

Portrait of the chancellor

|

|

| Born | c. 1506 |

| Died | 13 March 1573 |

| Spouse(s) | Marie Morin |

| Issue | Magdalaine de l'Hôpital |

Michel de l'Hôpital (born around 1506 – died March 13, 1573) was an important French lawyer and diplomat. He served as the Chancellor of France during a difficult time in French history. This period included the end of the Italian Wars and the beginning of the French Wars of Religion.

Michel's father was a doctor. He worked for a powerful noble called Constable Bourbon. Because of this, Michel spent his early life outside France. Later, his father worked for the House of Lorraine, and Michel became connected to Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine. He married Marie Morin, which helped him get a position in the Paris Parlement. This was a high court in France. In 1547, he became a diplomat for France at the Council of Trent. The next year, he helped Anne d'Este with her family's inheritance. This allowed her to marry Francis, Duke of Guise.

In 1553, Michel began working for Cardinal Lorraine. He received important jobs from the family. That year, he became a maître des requêtes for the king's household. This was a significant role. The next year, he became a président in the chambre des comptes. This gave him a lot of power over the kingdom's money. When his patron, Cardinal Lorraine, took control of France's finances, Michel joined the king's private council.

When the old chancellor, François Olivier, died, Lorraine suggested Michel as his replacement. Michel was a strong supporter of reforms. He often disagreed with the Parlements to pass new laws, like the Edict of Romorantin. He knew France had big money and religious problems. So, he pushed for a meeting called the Assembly of Notables. This meeting then called for a larger gathering, the Estates General. Michel opened this meeting and tried to guide it towards major changes. He worked hard to pass the Ordinance of Orléans, which came from these meetings.

After King François II died, Michel stayed important in royal politics. He supported the Queen Mother, Catherine de' Medici, in her religious policies. This often put him at odds with Cardinal Lorraine. He helped create and promote laws like the Edict of 19 April, July, and Saint-Germain. These laws made it easier for Protestants to practice their faith in France. He faced strong opposition from the Parlement, which did not want to legalize Protestantism.

After the first civil war, Michel's influence grew. He supported the king's decision to declare himself an adult in Rouen. This was also a way to show the Paris Parlement that they needed to follow the king's will. He successfully stopped Lorraine from bringing the Tridentine decrees into French law. The next year, he traveled with the court on a grand tour of France. Michel spoke to each Parlement, telling them to obey the king. At Moulins, he introduced many legal reforms. These reforms aimed to stop corruption, simplify laws, and limit the power of local governors. However, his influence started to fade. He had to give up many of his reforms because the king needed money for the second civil war.

During the civil war, he tried to negotiate with Prince Condé, who was attacking Paris. Michel suggested making some agreements with the rebels, but his ideas were not well received. After the Peace of Longjumeau in March 1568, he left the court in May. He felt his advice was no longer wanted by Catherine or the court. He returned in September for one last try. He opposed the crown's plan to sell church lands to fund a war against Protestants. When he failed, he lost his official seals, meaning he could no longer use his power as chancellor. He remained chancellor until his death. During the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, he and his daughter were protected by Catherine and the Duke of Guise. He died in March 1573.

Contents

Early Life and Family Connections

Michel de l'Hôpital was born in 1506 in Aigueperse. His father was a doctor for the Duchess of Lorraine. His father also worked for Constable de Bourbon. When Bourbon was accused of treason in 1525, Michel and his family had to leave France. They lived in Italy for a while. While there, Michel earned a degree in law. After Bourbon died, the family moved to the court of Lorraine. Michel continued his law studies in France.

His Daughter

During the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, Michel's only daughter, Magdelaine, was in Paris. She was in danger because she was Protestant and her father had supported religious tolerance. However, the Duke of Guise protected her. She later married Robert de Hurault. In 1555, Cardinal of Lorraine became the godfather to Michel's new grandson.

Michel's Beliefs

Michel de l'Hôpital was interested in stoicism, a type of philosophy. He believed in the importance of learning Greek. He thought that many governors and officials were corrupt. He also felt that the Estates General (a meeting of representatives from different parts of France) should meet more often. He saw it as a good way for the king to hear from his people. Michel believed that the Estates General should present their problems to the king, and the king would provide solutions.

What People Thought of Him

Some people who disagreed with Michel's religious policies thought he was secretly a Protestant. The famous writer Montaigne described Michel as a very capable and virtuous man.

Serving King François I

His Marriage and Role in Parlement

In 1532, Michel married Marie Morin. Her father was an important legal official. As part of her dowry (money or property given by the bride's family), Michel got a seat in the Paris Parlement. This gave him valuable experience. Later, when he was chancellor, he would sometimes clash with the Parlement. They felt he was betraying them since he had once been one of their own.

Diplomatic Work

In 1547, Michel was chosen to be the French ambassador to the Council of Trent. This was a very important meeting of the Catholic Church.

Serving King Henri II

Helping Anne d'Este

In 1548, Michel was in Ferrara, Italy. He helped Anne d'Este give up her family inheritance. This was necessary for her to marry the Duke of Guise. He then traveled with her back to France.

During the 1550s, Michel also worked for the Duchess of Savoy, Marguerite. She was King Henri II's sister and was open to Protestant ideas. She allowed Michel to help a Protestant writer, François Hotman, get a teaching job. Hotman later dedicated one of his books to Michel.

Working for the Lorraine Family

In 1553, Michel began working for Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine. He wrote strong arguments to support the family. In return, they helped him get the important job of maître des requêtes for the king's household. He argued that the Lorraine family was not "foreign" and praised the bravery of the Duke of Guise. In 1554, another future chancellor, Cheverny, bought Michel's old position in the Paris Parlement.

Financial Leadership

Michel became president of the chambres des comptes in 1554. This gave him experience with the kingdom's money matters. It also gave him a place on the king's private council. In 1558, he gave a speech at the wedding of the future King François II to Mary, Queen of Scots. He proudly said that this marriage would bring England under French influence without war.

Many French military leaders disliked the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, which ended the Italian Wars. However, Michel praised the treaty. He even wrote a poem supporting it.

Serving King François II

Financial Challenges

When King Henri II died, Cardinal Lorraine took charge of France's money. Michel became his main financial advisor. To help the kingdom's money problems, he suggested a plan to reschedule loans, raise taxes, and cut spending. These ideas were not popular. In some areas, people refused to pay new taxes. Peasants even left their villages to avoid them. The army was also made smaller, and many soldiers were not paid. This caused more problems for the government.

Becoming Chancellor

During the troubles of the Conspiracy of Amboise in 1560, Michel was away from France. He returned to court in May 1560. He was officially confirmed as Chancellor on June 30, 1560. The Guise family, especially Lorraine, strongly supported him for the job.

The Assembly of Notables

In May 1560, Michel helped pass the first law that eased the persecution of Protestants, called the Edict of Romorantin. The Parlement resisted this law, but Michel pushed it through. However, it was not fully put into practice. With the government struggling, Michel was among those who called for an Assembly of Notables. This meeting would discuss financial and religious solutions. Michel believed that only through these reforms could France be saved.

Michel opened the Assembly with a speech. He described France as a sick person, and the reforms as the cure. The meeting almost went off track when Admiral Coligny asked for Protestants to have their own churches. This angered Cardinal Lorraine. Michel took control, bringing the discussion back to money matters.

In July 1560, Michel passed a law about inheritance. He also issued laws about luxury spending in 1561 and 1563. He created a special court in Paris for merchant lawsuits. He expanded this to other towns in 1566.

In September 1560, Michel spoke to the Paris Parlement. He told them that new rebellions were happening daily across the country. He blamed those who used religion as an excuse for their actions. The Parlement was annoyed with him. They replied that the real problem was having two Protestants in high government positions.

The Condé Trial

Prince Condé did not attend the Assembly of Notables. He was involved in the Amboise Conspiracy and other troubles. The court ordered him to attend the Estates General in December. When he arrived, he was arrested and put on trial for treason. Michel and another judge refused to sign the guilty verdict. Condé was released in December after King François II died. Michel was responsible for ending the trial.

Serving King Charles IX

The Estates General Meeting

Michel de l'Hôpital gave the opening speech at the Estates General in 1560. He warned both radical Catholics and radical Protestants. He told Catholics to stop their violence and intolerance. He told Protestants to be patient. He stressed that everyone should be peaceful and follow the law until a church council could unite Christians. Since the Council of Trent had just restarted, Michel hoped the delegates would avoid religious debates.

He also told the delegates about France's money problems. He said the crown owed 43 million livres and needed to raise taxes. The delegates did not like this idea. So, the crown decided to sell church land to get money.

Michel wanted to reform the guild system (groups of skilled workers). He aimed to make it easier for apprentices and to reduce the guilds' control over jobs. He ordered that the money from religious groups linked to the guilds be given to local schools. However, the guilds fought back by changing their religious groups into official Catholic organizations. This helped them survive Michel's reforms until his influence lessened in 1567.

In April 1561, some powerful nobles, including Guise and Montmorency, secretly agreed to oppose Michel and Catherine de' Medici's religious policies. Michel was also trying to get the Ordinance of Orléans passed by the Parlement. He sent orders telling them to pass it without protest. The Parlement resisted, and Michel tried to win over senior judges. But the Parlement members were not interested.

Religious Tolerance Efforts

That same month, a law was passed that banned the words 'Papiste' (for Catholics) and 'Huguenot' (for Protestants). Michel had spoken against these terms earlier. The religious situation in France got worse in 1561. In June, Michel warned the Paris Parlement that Catholic children should stop parading with crosses. This angered Protestants and could cause riots. That same month, he helped create the Edict of July. This law still banned public Protestant worship but removed the death penalty for heresy. It also stopped people from searching their neighbors' homes for illegal worship. This effectively allowed private Protestant worship. Michel wanted to go even further and legalize Protestantism completely, but the council voted against it.

In September 1561, a religious meeting called the Colloquy of Poissy took place. Michel opened the meeting, asking Catholic clergy to listen to the Protestant speakers. He hoped they could find common ground. However, the talks failed over disagreements about the Eucharist (Communion).

The Edict of Saint-Germain

On January 3, 1562, Michel gave a speech to the Paris Parlement. He argued that religious tolerance for Protestants was necessary to avoid civil war. That same month, he helped create the Edict of Saint-Germain. This law officially allowed Protestants to worship, as long as they waited for the church to be reunited. Michel was helped by Catherine, Admiral Coligny, and Theodore Beza, a Protestant leader. The edict faced strong opposition from the Parlements and many Catholic nobles. Michel defended the edict, saying the only other choice was to expel or execute Protestants, which was not realistic.

After the Massacre of Wassy, France quickly moved towards civil war. Protestants began to arm themselves and take over towns. The Spanish ambassador tried to get Michel removed, saying his influence was bad for the crown. But the king did not remove him.

Michel's Time of Power

From 1563 to 1566, Michel and his supporters had a lot of influence. In March 1563, the first war of religion ended with the Edict of Amboise. This law gave limited tolerance to Protestants. Michel hoped that the civil war would make French citizens more forgiving of each other. Many Catholics were upset by the terms of the edict and tried to stop it.

In August 1563, King Charles IX was declared an adult in Rouen. This was combined with an official announcement of the Edict of Amboise. Michel and Catherine hoped that linking the two would make it harder for the court to oppose the peace. Rouen was chosen to punish the Paris Parlement for resisting their policies. The Paris Parlement was very upset by this. They protested, refusing to accept the king's majority or the peace. The king told them that their job was to administer justice, not to tell him what to do.

The Council of Trent's Return

In February 1564, the Council of Trent finally ended. Cardinal Lorraine returned to France, hoping the kingdom would adopt the council's recommendations. Michel opposed Lorraine. He argued that the Tridentine decrees would go against France's traditional church rights. He also said Lorraine was trying to gain power through the council. Lorraine was furious, calling Michel ungrateful and questioning his religion. Michel replied that his loyalty was to the king, not to the Guise family. He also pointed out that the Duke of Guise had caused problems with the Massacre of Wassy. After this argument, the council voted against adopting all the council's findings, much to Lorraine's disappointment.

The Grand Tour

Catherine decided to take King Charles IX on a grand tour of the kingdom. This was to make sure the edict was followed and to show the young king's authority. The court set off with 2000 people, including many important nobles. Michel was tasked with speaking to each of the kingdom's Parlements. He warned them to register the edict and respect the king's authority. He gave strong words to the resistant parlementaires of Aix-en-Provence. He told them the king was unhappy with their "disobedience." His speeches were met with silence. While at Crémieux, Michel changed the Edict of Amboise to stop Protestant churches from holding provincial meetings.

Reforms at Moulins

In February 1566, the court arrived at Moulins. An Assembly of Notables was held there. Michel argued that the main problem in the kingdom was poor justice. He criticized officials for corruption and greed. He also attacked the Parlements for being too proud and not following the king's laws. He wished for a time like King Louis IX's reign, when laws were simple.

Later that month, Michel presented the Ordinance of Moulins. This was a set of 86 articles for legal reform. The ordinance greatly reduced the Parlements' powers. It allowed the king to put laws into effect even if the Parlement disagreed. It also limited the power of governors and judges. Many government jobs were abolished. Groups and leagues were banned. The Edict of Amboise was upheld. This edict was a big threat to many powerful nobles. Although the edict demanded immediate approval, the Parlement ignored this. Michel had to accept many changes to the Ordinance in July. In 1566, Michel created a new financial office, the Surintendant des Finances. He appointed Marshal Cossé to this role.

While at Moulins, Lorraine arrived with a petition from the Parlement of Dijon. They were upset about a new rule that allowed Protestant ministers to visit the dying and teach the young. Lorraine argued this was a way to convert people. Michel had not consulted the council before issuing this rule. Michel and Lorraine had a heated argument. Catherine had to step in. She ordered the new rule to be burned. She also said that Michel could not approve laws without the council's permission.

In July 1567, Michel supported some changes to the Edict of Amboise. The area where Protestantism was banned was expanded from Paris to the wider Île de France region. Protestants were also barred from public office. Michel did this to calm the growing unrest in Paris.

The Surprise of Meaux and Decline

The Surprise of Meaux, where Protestants tried to capture the king and kill Lorraine, made Catherine lose trust in Michel's plans. Michel was with the court when they heard Protestants were planning an attack. He suggested staying firm, but others argued for fleeing to Paris. Catherine chose to flee. This led to another civil war.

While Paris was under attack by Condé's forces, Catherine sent Michel to negotiate. Condé made very demanding requests, which were unacceptable. Catherine became more tired of Michel. When he suggested compromises, she blamed him for the situation. To pay for the war, Michel's plan to reduce government jobs was canceled. In fact, more jobs were sold in January 1568, allowing officials to pass their positions to their heirs.

Losing Favor

The war ended with the Peace of Longjumeau, but the peace did not last. Michel, who believed in peace, found himself disagreeing with the royal council, which wanted to return to war. In May, he left the court, feeling his influence was over. He soon asked to be relieved of his office.

When he heard that the crown was negotiating with the Pope to sell church land for a war against Protestants, Michel returned to court in September to oppose it. The Pope saw Michel as a main opponent. Michel refused to approve the sale of church lands if it meant war on heresy. In a heated council meeting on September 19, Michel clashed with Lorraine. He argued that this plan would cause civil war. Lorraine accused Michel of being a hypocrite and said his wife and daughter were Protestants. Michel made a sarcastic joke about Lorraine's corruption, which angered Lorraine. Lorraine even tried to grab Michel's beard. Lorraine told Catherine that Michel was the cause of France's problems. Michel explained that Lorraine was the cause. It was clear to him that he could no longer change the crown's policy. He left for his estates near Étampes. A week later, on September 28, Michel had to give up his official seals. The crown then canceled the past tolerance laws and issued the Edict of Saint-Maur, which outlawed Protestantism. Michel could not have supported these steps.

On October 7, Jean de Morvillier received Michel's seals. Radical preachers in Paris celebrated Michel's removal.

His Writings

After losing his power, Michel began writing. His ideas in these writings were different from his earlier views. He no longer said Catholics should tolerate Protestants out of kindness. Instead, he argued that freedom of conscience was a natural right. He also stopped talking about the two faiths reuniting, as he no longer thought it was possible.

Final Years

The Parlement, knowing Michel had lost favor, tried in 1571 to get his official seals. This would have been symbolic. However, King Charles IX refused. He knew that giving the seals to the Parlement would mean recognizing them as a law-making body.

In 1572, during the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, Catherine sent guards to Michel's home to protect him. Some people wanted him dead. He died on his estates in March 1573.

Michel did not become very rich during his life, which was unusual for a high-ranking noble of his time. In his will, he left his property to his only daughter. He named his wife as the manager of his lands.

See also

In Spanish: Michel de L'Hospital para niños

In Spanish: Michel de L'Hospital para niños

- Tribunal de commerce de Paris, a court for business cases, founded by Michel de l'Hôpital in 1563