Italian Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Italian Wars |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French–Habsburg rivalry, the Anglo-French wars and the Ottoman-Habsburg wars | |||||||||

Left to right, top to bottom:

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a long series of fights between 1494 and 1559. These wars mostly happened in Italy. However, they also spread to other parts of Europe, like Flanders and Germany. The main groups fighting were the Valois kings of France and their rivals, the Habsburg rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain.

Different Italian states joined in at various times. England and the Ottoman Empire also played smaller roles. Before these wars, a group called the Italic League kept peace in Italy. But this peace ended when its leader, Lorenzo de' Medici, died in 1492. This allowed Charles VIII of France to invade Naples in 1494.

Even though Charles had to leave in 1495, his invasion showed something important. The Italian states were rich but divided, making them easy targets. This made Italy a major battleground for France and the Habsburgs. These wars were very brutal and happened during a time of big religious changes, called the Reformation. They also marked a shift from old-style medieval fighting to more modern warfare. New weapons like the arquebus (an early handgun) became common. Siege weapons also got much better.

After 1503, France often invaded Lombardy and Piedmont. They could hold land for a while but never for good. By 1557, both France and the Holy Roman Empire faced problems at home. These problems were often about religion. Spain also had a possible revolt in the Spanish Netherlands. The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559) ended the wars. France mostly left northern Italy. In return, France gained Calais from England and some lands in Lorraine. Spain became the main power in southern Italy, controlling Kingdom of Naples and Kingdom of Sicily. Spain also controlled the Duchy of Milan in northern Italy.

Contents

Why the Wars Started

The Republic of Venice and the Duchy of Milan had been fighting for a long time. These fights, called the Wars in Lombardy, ended in 1454 with the Treaty of Lodi. Soon after, a peace agreement called the Italic League was formed. This brought 40 years of peace and economic growth to Italy.

Lorenzo de' Medici, the ruler of Florence, was a big supporter of this League. He wanted to keep France and the Holy Roman Empire out of Italy. But Lorenzo died in 1492. This made the League much weaker. At the same time, France wanted to expand its power into Italy.

This idea came from Louis XI of France. He inherited a claim to the Kingdom of Naples in 1481. His son, Charles VIII, became king in 1483. Charles officially made Provence part of France in 1486. Its ports, Marseilles and Toulon, gave him easy access to the Mediterranean Sea. This allowed him to act on his plans for Italy. Before the First Italian War, Charles made deals with other European rulers. He wanted them to stay neutral. These deals included agreements with Henry VII of England in 1492 and Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor in 1493.

First Italian War (1494–1498)

This war began when Ludovico Sforza, the ruler of Milan, asked Charles VIII of France to invade Italy. Ludovico used France's claim to the throne of Naples as an excuse. He was in a rivalry with his nephew's wife, Isabella of Aragon. Isabella's father became Alfonso II of Naples in 1494. She asked him for help, which made Ludovico worried.

In September 1494, Charles invaded Italy. He said he wanted to use Naples as a base to fight the Ottoman Turks. In October, Ludovico became Duke of Milan. The French army marched through Italy with little resistance. They entered Pisa in November, Florence in November, and Rome in December. Charles had support from Girolamo Savonarola in Florence. Pope Alexander VI also let the French army pass through his lands.

In February 1495, the French reached Monte San Giovanni Campano in Naples. The Neapolitan soldiers there killed French messengers. The French then attacked the castle, killing everyone inside. This event, known as the "Sack of Naples," shocked Italy. Many became worried about France's power. On March 31, 1495, the League of Venice was formed. This group was against France and included Venice, Milan, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire.

Later, Florence, the Papal States, and Mantua joined the League. This group cut off Charles and his army from France. Charles's cousin, Louis d'Orleans, tried to take Milan. He claimed it through his grandmother. On June 11, he captured Novara. Ludovico Sforza became ill, and his soldiers almost rebelled. His wife, Beatrice d'Este, took charge of Milan and the siege of Novara. Louis was forced to surrender and leave.

Charles then moved north. On July 6, his army met the League at the Battle of Fornovo. The French pushed their enemies back and continued to Asti. Both sides claimed victory. However, the French were generally seen as winners because they continued their retreat. In the south, Ferdinand II of Naples regained control of his kingdom by September 1495. The French invasion didn't achieve much for France. But it showed that the rich Italian states were weak. This made other powerful countries want to intervene. Charles VIII died on April 7, 1498. Louis d'Orleans became the new king, Louis XII.

Italian Wars (1499–1504)

The next part of the conflict started with a rivalry between Florence and the Republic of Pisa. Pisa had been part of Florence since 1406. But it became independent during the French invasion in 1494. Pisa got help from Genoa, Venice, and Milan. These states were all suspicious of Florence's power. Ludovico Sforza again asked an outside power for help. This time, it was Emperor Maximilian I. Maximilian wanted to strengthen the League of Venice against France. But Florence thought he favored Pisa. Maximilian tried to force a settlement in 1496. He attacked the Florentine city of Livorno. But he had to leave due to lack of men and supplies.

After Charles VIII died in 1498, Louis XII planned to attack Milan again. He also wanted to claim Naples. Louis made agreements with England and Spain to secure his borders. In February 1499, Louis signed a military alliance with Venice against Ludovico. A French army of 27,000 men, led by Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, invaded Lombardy. In August, they attacked Rocca d'Arazzo. The French artillery quickly broke the walls. Louis ordered the execution of the town's soldiers and leaders. Other Milanese towns surrendered to avoid the same fate. Ludovico fled Milan with his children and went to Maximilian. On October 6, 1499, Louis entered Milan in triumph.

Florence then asked France for help to retake Pisa. Louis was not in a hurry to help them. He was busy defeating Ludovico, who tried to regain Milan. Ludovico was captured in April 1500 and stayed in a French prison for life. Louis needed to keep good relations with Florence. He had to cross their land to conquer Naples. So, on June 29, 1500, a French and Florentine army attacked Pisa. The French artillery again broke the walls. But the attacks failed, and the siege ended on July 11.

With Milan secure, Louis returned to France. He left Florence to blockade Pisa, which surrendered in 1509. Louis wanted to conquer Naples. So, on November 11, he signed the Treaty of Granada with Ferdinand II of Aragon. They agreed to divide Naples between them. Louis hoped this would let him get most of Naples without a costly war. Many people, like Niccolò Machiavelli, criticized this. They thought Louis gave too much away by inviting Spain into Naples.

In July 1501, the French army reached Capua. It was strongly defended by soldiers loyal to Frederick of Naples. Capua surrendered on July 24 after a short siege. But the city was then brutally attacked. Between 2,000 and 4,000 people died. This caused great fear across Italy. Other towns surrendered to avoid the same fate. On October 12, Louis made the Duke of Nemours his ruler in Naples. However, the Treaty of Granada didn't clearly decide who owned some key lands in Naples. Disputes quickly arose between France and Spain. This led to war in late 1502. The French were driven out of Naples again after losing battles at Cerignola in April 1503 and Garigliano in December.

War of the League of Cambrai

On October 18, 1503, Pope Julius II became Pope. As ruler of the Papal States, he worried about Venice's power in northern Italy. His hometown, Genoa, also disliked Venice. Maximilian, the Holy Roman Emperor, also felt threatened by Venice. Milan, controlled by Louis XII, was a long-time enemy of Venice. Ferdinand II, now king of Naples, wanted to get back Venetian ports on the southern Adriatic coast.

Julius brought these different groups together. Along with the Duchy of Ferrara, they formed the anti-Venetian League of Cambrai. They signed the agreement on December 10, 1508. The French largely defeated a Venetian army at Agnadello in May 1509. But Maximilian failed to capture Padua and left Italy. Pope Julius now saw Louis XII's power as a bigger threat. In February 1510, he made peace with Venice. In March, he agreed with the Swiss Cantons to get 6,000 soldiers.

After a year of fighting, Louis XII took large parts of the Papal States. In October 1511, Julius formed the anti-French Holy League. This group included Henry VIII of England, Maximilian, and Spain. A French army defeated the Spanish at Ravenna in April 1512. But their leader, Gaston de Foix, was killed. The Swiss recaptured Milan and put Ludovico's son, Massimiliano Sforza, back as duke. The League members then argued over dividing the spoils. Pope Julius died in February 1513, leaving the League without a strong leader.

In March, Venice and France formed an alliance. But from June to September 1513, the League won battles in Lombardy, Flanders, and England. Despite this, fighting continued in Italy. Neither side could get a clear advantage. On January 1, 1515, Louis XII died. His son-in-law, Francis I, became king. Francis continued the war and defeated the Swiss at Marignano in September 1515. This victory, along with Massimiliano Sforza's unpopularity, allowed Francis to retake Milan. The Holy League fell apart. Spain and Pope Leo X saw no reason to keep fighting.

In the Treaty of Noyon, signed in August 1516, Charles I of Spain recognized Francis as Duke of Milan. Francis gave his claim to Naples to Charles. Maximilian was left alone. In December, he signed the Treaty of Brussels, which confirmed France's control of Milan.

Italian War (1521–1526)

Maximilian died in January 1519. The German princes then elected Charles I of Spain as Emperor Charles V in June. This meant Spain, the Low Countries, and the Holy Roman Empire were all under one ruler. France was now surrounded by Habsburg lands. Francis I had also wanted to be Emperor. This added a personal rivalry between him and Charles. This rivalry became a major conflict of the 1500s.

Francis planned to attack Habsburg lands in Navarre and Flanders. First, he secured his position in Italy. He made a new alliance with Venice. He also expected support from Pope Leo X, who had backed him for Emperor. But Leo sided with Charles. In return, Charles promised to help him against Martin Luther and his ideas for the Catholic church. In November 1521, an army from the Empire and the Pope captured Milan. They put Francesco Sforza back as duke. Leo died in December. Adrian VI became Pope in January 1522. A French attempt to retake Milan failed at the Battle of Bicocca in April.

In May 1522, England joined the alliance against France. Venice left the war in July 1523. Adrian died in November, and Clement VII became Pope. Clement tried to make peace, but failed. France had lost land in Lombardy and was invaded by English, Imperial, and Spanish armies. But their enemies had different goals and didn't work together well. The Pope's goal was to stop either France or the Empire from becoming too strong. So, in late 1524, Clement secretly allied with Francis. This allowed Francis to launch another attack on Milan. On February 24, 1525, the French army suffered a huge defeat at the Battle of Pavia. Francis was captured and imprisoned in Spain.

This led to urgent talks to free Francis. France even sent a mission to Suleiman the Magnificent, asking for help from the Ottoman Empire. Suleiman didn't get involved this time. But it was the start of a long, though often secret, friendship between France and the Ottomans. Francis was finally released in March 1526. He signed the Treaty of Madrid. In it, he gave up French claims to Artois, Milan, and Burgundy.

War of the League of Cognac

Once Francis was free, his advisors said the Treaty of Madrid was not valid. They claimed he signed it under pressure. Pope Clement VII worried that the Emperor's power was a threat to the Pope's independence. So, on May 22, 1526, Clement formed the League of Cognac. Its members included France, the Papal States, Venice, Florence, and Milan. Many of the Emperor's soldiers were close to rebelling because they hadn't been paid. The Duke of Urbino, who led the League's army, hoped to use this confusion. But he waited for more Swiss soldiers before attacking.

The League won an easy victory on June 24 when Venice took Lodi. But the delay allowed Charles to gather new troops. He also supported a revolt in Milan in July against Francesco Sforza, who was again forced to leave. In September, Charles paid the Colonna family to attack Rome. The Colonna family competed with the Orsinis for control of the city. Clement had to pay them to leave. Francis invaded Lombardy in early 1527. His army was paid for by Henry VIII. Henry hoped this would help him get the Pope's support for divorcing his first wife, Katherine of Aragon.

In May, Imperial soldiers, many of whom followed Martin Luther, attacked Rome. They trapped Clement in the Castel Sant'Angelo. Urbino and the League army were nearby but did not help. The French marched south to help Rome. But they were too late to stop Clement from making peace with Charles V in November. Meanwhile, Venice, the strongest Italian state, refused to send more troops. Venice had suffered losses in earlier wars. Its sea trade was also threatened by the Ottomans. So, under Andrea Gritti, Venice tried to stay neutral. After 1529, it avoided fighting.

In April 1528, a French army attacked Naples. They were supported by a Genoese fleet. But disease forced them to leave in August. Both sides now wanted to end the war. After another French defeat at Landriano in June 1529, Francis agreed to the Treaty of Cambrai with Charles in August. This was called the "Peace of the Ladies." It was negotiated by Francis's mother, Louise of Savoy, and Charles's aunt, Margaret. Francis recognized Charles as ruler of Milan, Naples, Flanders, and Artois. Venice also made peace. Only Florence was left, as it had kicked out its Medici rulers in 1527.

At Bologna in the summer of 1529, Charles V was named King of Italy. He agreed to bring the Medici back to Florence for Pope Clement, who was a Medici himself. After a long siege, Florence surrendered in August 1530. Before 1530, people thought foreign powers would only interfere in Italy for a short time. For example, French takeovers of Naples and Milan were quickly reversed. Venice was often seen as the biggest threat because it was an Italian power. Many thought Charles V's power in Italy would also pass quickly. But instead, it began a long period of Imperial control. One reason was Venice's decision to focus on protecting its sea empire from the Ottomans after 1530.

Italian War (1536–1538)

The Treaty of Cambrai had put Francesco Sforza back as Duke of Milan. It also said that if he died without children, Charles V would inherit the duchy. Francesco died on November 1, 1535. Francis refused to accept this. He argued that Milan, along with Genoa and Asti, was rightfully his. So, he prepared for war again. In April 1536, supporters of France in Asti forced out the Imperial soldiers. A French army led by Philippe de Chabot took Turin. However, they failed to take Milan.

In response, a Spanish army invaded Provence and captured Aix in August 1536. But they soon left. This expedition wasted resources that were needed in Italy. The Franco-Ottoman alliance of 1536 was a big agreement. It covered trade and diplomacy. It also planned a joint attack on Genoa. French land forces would be supported by an Ottoman fleet.

The French found that Genoa's defenses had been strengthened. A planned uprising inside the city also failed. Instead, the French took the towns of Pinerolo, Chieri, and Carmagnola in Piedmont. Fighting continued in Flanders and northern Italy throughout 1537. The Ottoman fleet attacked coastal areas around Naples. This raised fears of invasion across Italy. Pope Paul III, who became Pope in 1534, wanted to end the war. He brought the two sides together at Nice in May 1538. The Truce of Nice, signed in June, agreed to a ten-year stop in fighting. It left France in control of most of Savoy, Piedmont, and Artois.

Italian War (1542–1546)

The 1538 truce didn't solve the main problems between Francis and Charles. Francis still claimed Milan. Charles insisted he follow the earlier treaties. Their relationship broke down in 1540. Charles made his son Philip Duke of Milan. This meant Milan could never go back to France. In 1541, Charles made a terrible attack on the Ottoman port of Algiers. This greatly weakened his army. Suleiman then restarted his alliance with France. With Ottoman support, Francis declared war on the Holy Roman Empire again on July 12, 1542. This started the Italian War of 1542–46.

In August, French armies attacked Perpignan on the Spanish border. They also attacked Artois, Flanders, and Luxemburg. Imperial defenses were much stronger than expected. Most of these attacks were easily stopped. In 1543, Henry VIII allied with Charles. He agreed to support Charles's attack in Flanders. Neither side made much progress. A combined French and Ottoman fleet, led by Hayreddin Barbarossa, captured Nice in August. They also attacked the citadel. But winter came, and a Spanish fleet arrived, forcing them to leave. A joint attack by Christian and Islamic troops on a Christian town was shocking. Especially when Francis let Barbarossa use the French port of Toulon as a winter base.

On April 14, 1544, a French army led by Francis, Count of Enghien, defeated the Imperials at Ceresole. This victory had limited value. They didn't make progress elsewhere in Lombardy. The Imperial position got stronger at Serravalle in June. Alfonso d'Avalos defeated a group of hired soldiers led by Piero Strozzi. An English army captured Boulogne in September. Imperial forces advanced close to Paris. However, Charles's treasury was empty. He also worried about the Ottoman navy in the Mediterranean Sea. So, on September 14, Charles agreed to the Treaty of Crépy with Francis. This treaty mostly returned things to how they were in 1542. The agreement did not include Henry VIII. His war with France continued until 1546. Then, the two countries made peace, and Henry kept Boulogne.

Italian War (1551–1559)

Francis died on March 31, 1547. His son, Henry II of France, became king. Henry continued to try and restore France's power in Italy. He was encouraged by Italian exiles and his cousin, Francis, Duke of Guise. Guise claimed the throne of Naples through his grandfather. Henry first strengthened his diplomatic position. He restarted the Franco-Ottoman alliance. He also supported their capture of Tripoli in August 1551. Even though Henry was a strong Catholic and punished Protestants at home, he signed the Treaty of Chambord in January 1552. This was with several Protestant princes in the Empire. It gave him control of the Three Bishoprics of Toul, Verdun, and Metz.

The Second Schmalkaldic War started in March 1552. French troops took the Three Bishoprics and invaded Lorraine. In 1553, a French and Ottoman force captured the Genoese island of Corsica. French-backed exiles from Tuscany, supported by Henry's wife, Catherine de' Medici, took control of Siena. This led to conflict with Cosimo de' Medici, the ruler of Florence. Cosimo defeated a French army at Marciano in August 1554. Siena held out until April 1555. It was then absorbed by Florence and became part of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in 1569.

In July 1554, Philip II of Spain became king of England. This happened through his marriage to Mary I. In November, he also received the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily from his father. His father also confirmed him as Duke of Milan. In January 1556, Charles officially stepped down as Emperor. He divided his lands. The Holy Roman Empire went to his brother, Ferdinand I. Spain, its lands overseas, and the Spanish Netherlands went to Philip. Over the next century, Naples and Lombardy became a major source of soldiers and money for Spain. This was for the Army of Flanders during the Eighty Years' War (1568 to 1648).

England entered the war in June 1557. The fighting moved to Flanders. A Spanish army defeated the French at St. Quentin in August. Despite this, in January 1558, the French took Calais. England had held Calais since 1347. Losing it greatly reduced England's ability to interfere in Europe. The French also captured Thionville in June. But peace talks had already started. Henry was busy with internal conflicts that led to the French Wars of Religion in 1562. The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis on April 3, 1559, ended the Italian wars. Corsica was returned to Genoa. Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, re-established the Savoyard state in northern Italy as an independent country. France kept Calais and the Three Bishoprics. Other parts of the treaty mostly returned things to how they were in 1551. Finally, Henry II and Philip II agreed to ask Pope Pius IV to recognize Ferdinand as Emperor. They also agreed to restart the Council of Trent.

What Happened Next

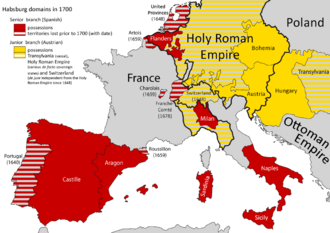

The balance of power in Europe changed a lot during the Italian Wars. France's growing power in Italy around 1494 made Austria and Spain join an anti-French group. This formed a "Habsburg ring" around France. This happened through royal marriages that led to Charles V inheriting a huge amount of land. On the other hand, the last Italian war ended with Charles V dividing his Habsburg Empire. It was split between the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs.

Philip II of Spain inherited the kingdoms Charles V held in Spain, southern Italy, and South America. Ferdinand I became Charles V's successor in the Holy Roman Empire. This empire stretched from Germany to northern Italy. He also became the king of the Habsburg monarchy in his own right. The Habsburg Netherlands and the Duchy of Milan remained linked to the king of Spain. But they were still part of the Holy Roman Empire.

The splitting of Charles V's empire was good for France. France also gained land like Calais and the Three Bishoprics. However, the Habsburgs had become the main power in Europe and Italy. This was at the expense of the French Valois kings. To achieve its goals, France had to stop fighting Habsburg power. It also had to give up its claims in Italy. Henry II also gave the Savoyard state back to Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy. Emmanuel Philibert settled in Piedmont. Corsica was returned to the Republic of Genoa. Because of these mixed results, the end of the Italian Wars is seen as a mixed outcome for France.

At the end of the wars, Italy was mostly divided. The Spanish Habsburgs ruled the south. The Austrian Habsburgs formally controlled areas in the north. The most important Italian power left was the Papacy in central Italy. It kept a lot of cultural and political influence during the Catholic Reformation. The Council of Trent, which had stopped during the war, was restarted. This was part of the peace treaties. It finally ended in 1563.

Military Changes

The Italian Wars brought big changes in military technology and tactics. Some historians think they mark the point between medieval and modern battlefields. The historian Francesco Guicciardini wrote about the French invasion of 1494. He said that "sudden and violent wars broke out." States were conquered faster than it used to take to capture a small house. Taking a city became very quick, happening in days or hours.

Foot soldiers changed a lot during these wars. They went from mainly using pikes and halberds. They became more flexible, using arquebusiers (gunmen), pikemen, and other troops. Landsknechts and Swiss mercenaries were very important early in the wars. But the Italian War of 1521 showed the power of many firearms used together. This was seen in formations that combined pikes and guns.

A small fight in 1503 between French and Spanish forces first showed how useful arquebuses were. The Spanish general, Gonzalo de Córdoba, pretended to retreat. He lured French cavalry between two groups of his arquebusiers. As the French rode between them, bullets hit them from both sides. Before the French could attack the gunmen, a Spanish cavalry charge broke the French forces. They were forced to retreat. The French army escaped, but the Spanish caused many casualties.

Firearms were so successful in the Italian Wars that Niccolò Machiavelli wrote about them. He said that everyone in a city should know how to fire a gun.

Veterans and Explorers

Many conquistadors (Spanish conquerors), like Hernán Cortés, thought about serving in Italy. But they chose to go to Spanish America instead. Many veterans from Naples and southern Italy later moved there. They went as colonists or soldiers. Experience in Italy was often needed for military jobs. However, some thought conditions in the Americas were much tougher. This was because "no plunder of value could be obtained" from the people there.

Italian veterans included Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar. He conquered Cuba in 1511. Francisco de Carvajal and Pedro de Valdivia both fought at Pavia in 1526. Carvajal and Valdivia served with the Pizarro brothers in Peru. This was during their fight with Spanish rival Diego de Almagro in 1538. Carvajal stayed with the Pizarros. Valdivia started the conquest of Chile and began the Arauco War. The two men fought on opposite sides in the 1548 Battle of Jaquijahuana. Carvajal was executed after being captured. Valdivia died in 1553 at Tucapel.

Cavalry

Heavy cavalry, the last form of the fully armored medieval knight, were still important in the Italian Wars. French gendarmes were usually successful against other heavy cavalry. This was mostly because of their excellent horses. But they were very vulnerable to pikemen. The Spanish used heavy cavalry and light cavalry, called Jinetes, for quick attacks.

Artillery

Artillery, especially field artillery, became a vital part of any strong army during the wars. When Charles VIII invaded in 1494, he brought the first truly mobile siege guns. These were culverins and bombards. They had new features, like being mounted on wheeled carriages. Horses pulled them, not oxen, which was the usual way. This allowed them to be moved quickly to attack enemy strongholds. Their lightness made them mobile. This was achieved by using methods to cast bronze church bells. Perhaps the most important improvement was the creation of the iron cannonball. Stone balls often shattered when they hit. The combination meant Charles could destroy castles in an hour. These castles had resisted sieges for months or even years.

Studying the Wars

The Italian Wars are some of the first major conflicts with many detailed accounts. These accounts were written by people involved in the wars. This is because many commanders could read and write well. The invention of modern printing, which was still new, also helped record the conflict. Important historians of this time include Francesco Guicciardini and Paolo Sarpi.

Names of the Wars

The names of the different parts of the Italian Wars are not always the same. Historians use different names. Some wars might be split or combined differently. This means the numbering systems can be different in various sources. The wars might be called by their dates or by the kings who fought in them. Usually, the Italian Wars are grouped into three main periods: 1494–1516; 1521–1530; and 1535–1559.

First-Hand Accounts

A major first-hand account for the early part of the Italian Wars is Francesco Guicciardini's Storia d'Italia (History of Italy). He wrote it during the conflict. He had access to information about the Pope's affairs, which made his account very valuable.

See also

In Spanish: Guerras italianas (1494-1559) para niños

In Spanish: Guerras italianas (1494-1559) para niños