Battle of Ceresole facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Ceresole |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian War of 1542–1546 | |||||||

Bataille de Cérisoles, 14 avril 1544 (oil on canvas by Jean-Victor Schnetz, 1836–1837) depicts François de Bourbon at the end of the battle. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~11,000–13,000 infantry, ~1,500–1,850 cavalry, ~20 guns |

~12,500–18,000 infantry, ~800–1,000 cavalry, ~20 guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~1,500–2,000+ dead or wounded | ~5,000–6,000+ dead or wounded, ~3,150 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Ceresole happened on April 11, 1544, near the village of Ceresole d'Alba in Italy. This battle was part of the Italian War of 1542–1546. A French army, led by François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien, fought against the combined forces of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. The Imperial and Spanish forces were commanded by Alfonso d'Avalos d'Aquino, Marquis del Vasto.

The French army won the battle, causing many losses for the Imperial troops. However, the French did not manage to capture Milan afterwards, which was their main goal. This battle is known for being very bloody, especially in the center where soldiers fought closely. It also showed that traditional heavy cavalry (soldiers on horseback) were still important, even as new infantry (foot soldiers) tactics became common.

Contents

Before the Battle

The war in northern Italy had been going on for some time. In 1543, a combined French and Ottoman fleet captured the city of Nice. Meanwhile, Imperial-Spanish forces moved from Lombardy towards Turin, which was held by the French. By the winter of 1543–1544, neither side was making much progress in the Piedmont region.

The French, led by the Sieur de Boutières, held Turin and several other towns. The Imperial army, under d'Avalos, controlled fortresses around the French territory. Both armies spent their time attacking each other's smaller strongholds. D'Avalos captured Carignano, a town close to Turin, and made it stronger with defenses.

King Francis I of France then sent François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien to lead the French army in Italy. Enghien was young and had no experience leading a whole army. Francis also sent more troops, including heavy cavalry and French infantry. In January 1544, Enghien began to lay siege to Carignano. The French hoped that d'Avalos would have to come and try to save the city. This would force him into a big battle.

Enghien sent a messenger, Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme, seigneur de Montluc, to ask King Francis for permission to fight a pitched battle (a planned, open battle). King Francis agreed, as long as Enghien's captains also agreed. Montluc returned with many young noblemen who wanted to join the fight.

D'Avalos waited for more soldiers, called landsknechts, sent by Emperor Charles V. Then, he marched from Asti towards Carignano. His army had about 12,500 to 18,000 foot soldiers, including many arquebusiers (soldiers with early firearms). He had fewer cavalry (horse soldiers), only about 800 to 1,000. D'Avalos knew his cavalry was weaker, but he trusted his experienced foot soldiers.

Enghien learned that d'Avalos was coming. He left some troops at Carignano and gathered the rest of his army at Carmagnola. On April 10, d'Avalos's forces reached Ceresole d'Alba. Enghien decided to fight on ground he had chosen. On the morning of April 11, the French moved to a spot about three miles away and waited. Enghien believed the open ground would help his cavalry. The French army had about 11,000 to 13,000 foot soldiers and 1,500 to 1,850 cavalry. Both armies had about 20 cannons.

The Battle Begins

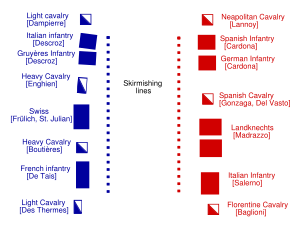

Setting Up the Armies

Enghien's troops were placed along the top of a ridge. The middle of the ridge was higher, so the French army's wings (sides) could not see each other. The French army was split into three main parts: the center, the right side, and the left side.

- On the far right, there were about 450-500 light cavalry.

- To their left, about 4,000 French foot soldiers.

- Further left, 80 heavy cavalry.

- In the center, about 4,000 experienced Swiss soldiers.

- To their left, Enghien himself with about 450 heavy cavalry and volunteers.

- The far left had two groups of foot soldiers, 3,000 from Gruyères and 2,000 Italians.

- On the very far left, about 400 mounted archers acting as light cavalry.

The Imperial army lined up on a similar ridge facing the French.

- On their far left, 300 Florentine light cavalry.

- Next to them, 6,000 Italian foot soldiers.

- In the center, 7,000 landsknechts (German mercenary foot soldiers).

- To their right, d'Avalos with about 200 heavy cavalry.

- The Imperial right side had about 5,000 German and Spanish foot soldiers.

- On the very far right, 300 Italian light cavalry.

| French (François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien) |

Spanish–Imperial (Alfonso d'Avalos d'Aquino, Marquis del Vasto) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | Strength | Commander | Unit | Strength | Commander |

| Light cavalry | ~400 | Dampierre | Neapolitan light cavalry | ~300 | Philip de Lannoy, Prince of Sulmona |

| Italian infantry | ~2,000 | Descroz | Spanish and German infantry | ~5,000 | Ramón de Cardona |

| Gruyères infantry | ~3,000 | Descroz | |||

| Heavy cavalry | ~450 | François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien | Heavy cavalry | ~200 | Carlo Gonzaga |

| Swiss | ~4,000 | William Frülich of Soleure and St. Julian | Landsknechte | ~7,000 | Eriprando Madruzzo |

| Heavy cavalry | ~80 | Sieur de Boutières | |||

| French (Gascon) infantry | ~4,000 | De Tais | Italian infantry | ~6,000 | Ferrante Sanseverino, Prince of Salerno |

| Light cavalry | ~450–500 | Des Thermes | Florentine light cavalry | ~300 | Rodolfo Baglioni |

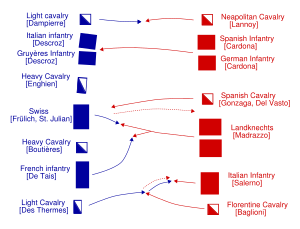

First Moves

As d'Avalos's troops arrived, both armies tried to hide their full size. Enghien told his Swiss soldiers to lie down behind the ridge. D'Avalos sent arquebusiers (soldiers with firearms) to find the French army's edges. Enghien sent about 800 of his own arquebusiers to slow down the Imperial advance.

The fighting between these small groups lasted almost four hours. An observer called it "a pretty sight" for those watching safely. As both armies revealed their positions, they brought up their cannons. The cannon fire lasted for several hours but did little damage. This was because of the distance and good cover for the soldiers.

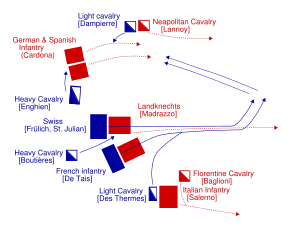

The small fights ended when Imperial cavalry seemed ready to attack the French arquebusiers. The French light cavalry then charged forward. D'Avalos saw this and ordered his entire army to advance. On the southern side of the battlefield, the French light cavalry pushed back the Florentine cavalry. They then charged into the Italian foot soldiers. The Italian formation held, and the French commander was captured. But by the time the Italians were ready to move again, the main fight in the center was already decided.

The Main Fight

The French foot soldiers, mostly from Gascony, started moving down the slope towards the Italian soldiers. A French commander suggested they attack the advancing landsknechts instead. This idea was taken, and the French turned to hit the landsknechts from the side. The landsknecht commander split his group into two parts. One part moved to fight the French, while the other continued up the slope towards the Swiss soldiers.

At this time, foot soldiers often mixed arquebusiers (with firearms) and pikemen (with long spears). Both the French and Imperial armies had these mixed units. This made close-up fighting very bloody. Usually, arquebusiers were on the sides of the pikemen. But at Ceresole, the French had pikemen in the first row, followed immediately by arquebusiers. These arquebusiers were told to wait until the two groups met before firing.

The Swiss soldiers, seeing the French fighting one group of landsknechts, finally moved down the hill to meet the other group. Both large groups of foot soldiers pushed against each other with their pikes. Then, a group of French heavy cavalry charged into the side of the landsknechts. This broke their formation and sent them running down the slope. The Imperial heavy cavalry, who were supposed to attack the Swiss, turned and ran away. Their commander was captured.

The Swiss and French foot soldiers then killed many of the remaining landsknechts. The landsknechts were in a tight group, making it hard to escape. The road was covered with dead bodies. The Swiss were especially harsh, wanting revenge for how their soldiers were treated earlier. Most of the landsknecht officers were killed. The German foot soldiers were completely destroyed. Seeing this, the Italian commander decided the battle was lost and left with his soldiers.

Fighting in the North

On the northern side of the battlefield, things went differently. The French cavalry quickly defeated the Imperial light cavalry. However, the Italian and Gruyères foot soldiers on the French side broke and ran away without much of a fight. Their officers were killed. As the Imperial foot soldiers moved past the original French line, Enghien charged them with all his heavy cavalry. This fight happened on the other side of the ridge, hidden from the rest of the battle.

On their first charge, Enghien's cavalry broke through a part of the Imperial formation. They pushed to the back, losing some of their own men. As the Imperial soldiers closed their ranks, the French cavalry turned and charged again, facing heavy fire from firearms. This charge cost many lives and still did not break the Imperial group. Enghien, now joined by his light cavalry, made a third charge. This also failed to win the fight. Only about a hundred of his heavy cavalry were left.

Enghien thought the battle was lost. But then, the Swiss commander arrived from the center of the battlefield. He reported that the Imperial forces there had been completely defeated.

The Imperial troops in the north heard about the defeat of the landsknechts at the same time as Enghien. The Imperial group turned and retreated back to where they started. Enghien followed closely with his remaining cavalry. He was soon joined by Italian mounted arquebusiers. These soldiers would get off their horses to fire their weapons, then get back on. They were able to bother the Imperial group enough to slow their retreat. Many of the Imperial foot soldiers were killed as they tried to surrender. About 3,150 men were taken as prisoners. A few, like the German infantry commander, managed to escape.

After the Battle

The Battle of Ceresole had a very high number of deaths and injuries. About 28% of all soldiers involved were killed or wounded. Imperial sources say between 5,000 and 6,000 Imperial soldiers died, but some French sources claim up to 12,000. Many officers were killed, especially among the landsknechts. Many who survived were captured, including important commanders. The French had fewer losses, but still about 1,500 to 2,000 killed. This included many officers and a large part of Enghien's heavy cavalry.

Even though the Imperial army was destroyed, the battle did not change the war much. The French army continued to besiege Carignano, which surrendered after several weeks. But soon after, Enghien had to send many of his foot soldiers and half of his heavy cavalry to Picardy. This was because Emperor Charles V had invaded that area. Without enough soldiers, Enghien could not capture Milan. The war ended with things mostly going back to how they were before in northern Italy.

How We Know About the Battle

Many detailed stories about the battle from that time still exist. French accounts include writings by Martin Du Bellay and Blaise de Montluc, who were both there. The Sieur de Tavannes, who was with Enghien, also wrote about it. The most complete account from the Imperial side is by Paolo Giovio. Even with some differences from other stories, it gives "valuable notes" on things the French writers missed.

Historians today are very interested in how firearms were used in this battle. They also study the huge number of deaths among the foot soldiers. The way pikemen and arquebusiers were mixed was seen as too costly, and it was not used again. In later battles, arquebuses were mostly used for small fights or from the sides of larger groups of pikemen. Ceresole also shows that traditional heavy cavalry (soldiers on horseback) were still important. Even though Enghien's charges did not completely break the enemy, a small group of heavy cavalry was enough to defeat foot soldiers who were already fighting other foot soldiers. Cavalry was also important because they were the only ones expected to accept an enemy's surrender. Foot soldiers often did not take prisoners.

Images for kids

-

Swiss mercenaries and landsknechte fighting with pikes (engraving by Hans Holbein the Younger, early 16th century)

-

Swiss mercenaries and landsknechte fighting with pikes (engraving by Hans Holbein the Younger, early 16th century)

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Cerisoles para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Cerisoles para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |