Hans Holbein the Younger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hans Holbein the Younger

|

|

|---|---|

| Hans Holbein der Jüngere | |

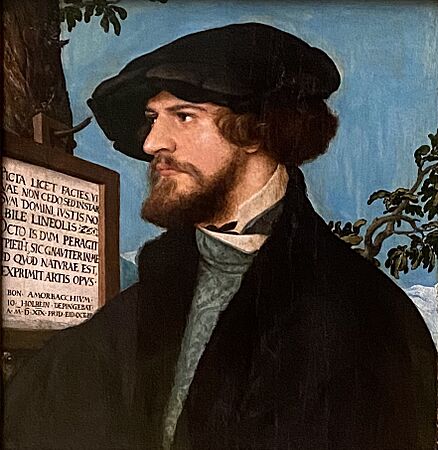

Self-portrait (c. 1542/43)

|

|

| Born | c. 1497 Augsburg (free imperial city), Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | October or November 1543 (aged 45–46) |

| Nationality | German, Swiss |

| Known for | Portraits |

|

Notable work

|

The Ambassadors |

| Movement | Northern Renaissance |

Hans Holbein the Younger (UK: /ˈhɒlbaɪn/ HOL-byne, US: /ˈhoʊlbaɪn, ˈhɔːl-/ hohl-BYNE-,_-HAWL--; German: Hans Holbein der Jüngere; c. 1497 – between 7 October and 29 November 1543) was a talented German-Swiss painter. He is known as one of the best portrait artists of the 1500s. He also created religious art and designs for books. People call him "the Younger" to tell him apart from his father, Hans Holbein the Elder, who was also a famous painter.

Holbein was born in Augsburg, Germany. He started his career in Basel, Switzerland. There, he painted large wall murals and religious artworks. He also designed stained glass windows and pictures for books. He became famous for his portraits, especially those of the smart writer Desiderius Erasmus.

When the Protestant Reformation changed Basel, Holbein kept working for both new and old religious groups. His art style mixed older German art with new ideas from Italy, France, and the Netherlands. This made his art unique.

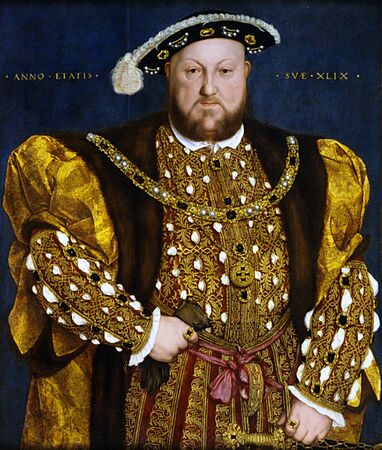

In 1526, Holbein moved to England to find more work. He had a letter of recommendation from Erasmus. He quickly became popular among important thinkers like Thomas More. After four years, he went back to Basel. But in 1532, he returned to England. He worked for Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell. By 1535, he became the official King's Painter for Henry VIII of England.

As the King's Painter, Holbein made portraits of the royal family and nobles. These paintings show us what the court looked like during Henry VIII's reign. Holbein also designed jewelry and other fancy objects. People admired his art from the very beginning. He was called "the Apelles of our time," meaning he was as good as a legendary ancient Greek painter.

Holbein's art is often called "realist" because he painted with amazing detail. His portraits were famous for looking exactly like the people. Thanks to him, we know what many important figures like Erasmus and Thomas More looked like. But Holbein didn't just paint what he saw. He added hidden symbols and meanings to his art. This makes his paintings interesting for scholars even today.

Holbein's Life Story

Early Years as an Artist

Hans Holbein was born in Augsburg, Germany, in the winter of 1497 or 1498. His father, Hans Holbein the Elder, was a painter. Hans and his older brother, Ambrosius Holbein, followed in their father's footsteps. Their father had a busy art workshop in Augsburg.

Around 1515, Hans and Ambrosius moved to Basel, Switzerland. Basel was a big center for learning and printing books. They became apprentices to Hans Herbster, a leading painter in Basel. The brothers designed woodcuts and metalcuts for printers. In 1515, they drew funny pictures in the margins of a copy of The Praise of Folly by the famous scholar Desiderius Erasmus. These drawings showed Holbein's cleverness.

In 1517, Holbein and his father worked in Lucerne, painting murals for a merchant's house. Holbein also designed pictures for stained glass. He probably visited northern Italy that winter. Many experts believe he studied the works of Italian masters like Andrea Mantegna.

In 1519, Holbein returned to Basel. His brother Ambrosius disappears from records around this time, likely meaning he passed away. Holbein quickly set up his own busy workshop. He joined the painters' guild and became a citizen of Basel. He married Elsbeth Binsenstock-Schmid, a widow with a young son. They had four children together: Philipp, Katharina, Jacob, and Küngold.

Holbein was very busy in Basel during this time. The city was changing due to the Lutheran movement. He painted large murals for the Town Hall. He also created many religious paintings and designs for stained glass.

He illustrated books for the publisher Johann Froben. His famous designs include the Dance of Death and illustrations for the Old Testament. He also designed special alphabets with pictures of gods and famous people. These woodcuts helped him become better at showing feelings and space in his art.

Holbein also painted portraits in Basel. These included a double portrait of Jakob and Dorothea Meyer. In 1519, he painted the young scholar Bonifacius Amerbach. These portraits showed his improving style. In 1523, he painted his first portraits of Erasmus. These paintings made Holbein known internationally. In 1524, Holbein visited France, hoping to find work for the king. When he decided to go to England in 1526, Erasmus recommended him to his friend Thomas More. Erasmus wrote that "the arts are freezing in this part of the world," meaning Holbein needed to find work elsewhere.

Working in England (1526–1528)

Holbein stopped in Antwerp on his way to England. There, he met the painter Quentin Matsys. Then, he went to England, where Sir Thomas More welcomed him. More wrote that Holbein was a "wonderful artist." Holbein painted the famous Portrait of Sir Thomas More. He also planned a group portrait of More's family, which was very new for the time.

During this first visit to England, Holbein mostly worked for friends of Erasmus. He painted William Warham, the Archbishop of Canterbury. He also painted Nicholas Kratzer, an astronomer who taught the More family. Holbein did not work for the king on this trip. But he painted other important people, like Sir Henry Guildford and his wife, and Anne Lovell. In May 1527, Holbein also painted a large scene of a battle for French visitors. He even helped design a special ceiling with planetary signs for a dinner.

Back in Basel (1528–1532)

In August 1528, Holbein bought a house in Basel. He probably returned to keep his citizenship, as he was only allowed to be away for two years. He had earned good money in England. In 1531, he bought a second house nearby.

During this time in Basel, he painted The Artist's Family. This painting shows his wife Elsbeth with their two oldest children, Philipp and Katherina. It reminds people of paintings of the Virgin Mary and Jesus. Art experts call it one of the most touching portraits ever made.

Basel had become a difficult city while Holbein was away. Reformers, following the ideas of Huldrych Zwingli, destroyed religious images in churches. In 1529, Erasmus felt he had to leave Basel. Some of Holbein's religious art was probably destroyed. Holbein's own religious views are not fully clear. He was asked why he didn't attend the new church service. But soon after, he was listed among those who "have no serious objections."

Holbein still had support from the new leaders. The city council paid him a fee and asked him to finish the Town Hall frescoes. These new paintings showed stories from the Old Testament. Holbein also worked for his old clients. He added figures to Jakob Meyer's family altarpiece. His last job in Basel was decorating two clock faces on the city gate in 1531. There was less art work in Basel, which might be why he decided to return to England in early 1532.

Working for King Henry VIII (1532–1540)

When Holbein returned to England, things were changing a lot. King Henry VIII was planning to divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn. This went against the Pope. Holbein's old friend, Sir Thomas More, was against the King's actions. More resigned as a top official in 1532 and was later executed in 1535. Holbein seemed to move away from More's group. Instead, he found favor with the new powerful people, like the Boleyn family and Thomas Cromwell. Cromwell became the King's secretary in 1534 and controlled many parts of the government, including art.

At first, Holbein painted portraits of German merchants. These merchants lived and worked in London. Holbein rented a house nearby. His portrait of Georg Giese shows the merchant surrounded by detailed symbols of his business. His painting The Ambassadors is one of his most famous works from this time. It shows two French visitors, Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve. The painting has many hidden symbols and a distorted skull. These symbols refer to learning, religion, death, and illusions.

There are no certain portraits of Anne Boleyn by Holbein. This might be because her memory was erased after she was executed in 1536. But Holbein definitely worked for Anne and her friends. He designed a special cup for her and also jewelry and books. He also drew several women who were part of her group.

At the same time, Holbein worked for Thomas Cromwell. Cromwell was leading Henry VIII's religious changes. Holbein created images to support the King. He made woodcuts that criticized monks and a title page for an English Bible. Henry VIII was spending a lot of money on art to show his power.

By 1536, Holbein was the King's Painter. He earned a good salary, though he wasn't the highest-paid artist. In 1537, Holbein painted his most famous image of Henry VIII. It shows the King standing in a powerful pose. A large wall painting at Whitehall Palace showed the King like this, with his father behind him. This mural was destroyed in a fire in 1698. But we know what it looked like from copies.

Jane Seymour, Henry's third wife, died in October 1537 after giving birth to their son, Edward VI. Holbein painted a portrait of the baby prince about two years later. Holbein's last portrait of Henry VIII is from 1543.

Holbein's portrait style changed after he started working for the King. He focused more on the person's face and clothes. He left out many props and detailed backgrounds. He used this clear, precise style for small miniature portraits and for large ones. For example, he traveled to Brussels in 1538 to sketch Christina of Denmark for the King. Henry VIII was thinking of marrying her. An English ambassador said that another artist's drawing of Christina was "sloppy" compared to Holbein's.

In 1539, Holbein painted Anne of Cleves for Henry VIII. This was the woman Henry married. An English official said Holbein "expressed their images very lively." However, Henry was disappointed with Anne when he met her. He divorced her soon after. Some people say Holbein's portrait made Anne look better than she was. But others said she was attractive, just dressed in heavy German clothes. This marriage problem was one reason why Thomas Cromwell lost his power.

Final Years and Death (1540–1543)

Holbein had managed to survive when his earlier patrons, Thomas More and Anne Boleyn, fell from power. But Cromwell's sudden arrest and execution in 1540 hurt his career. Holbein remained the King's Painter, but no one could replace Cromwell as a patron. It was Holbein's portrait of Anne of Cleves that partly led to Cromwell's downfall. Henry was angry about his marriage and blamed Cromwell.

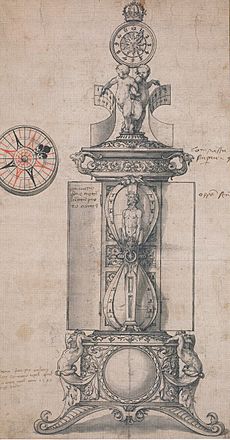

Holbein now took on private jobs, painting more portraits of merchants. He also painted some of his best miniature portraits. These included small paintings of Henry and Charles Brandon, sons of Henry VIII's friend. Holbein also got work from important courtiers, especially Anthony Denny. He even borrowed money from Denny. He painted Denny's portrait in 1541 and designed a special clock-salt for him two years later.

Holbein might have visited his wife and children in Basel in late 1540. He had lived apart from Elsbeth since 1532.

Hans Holbein died between October 7 and November 29, 1543, when he was about 45 years old. Some people say he died of the plague. Holbein made his will on October 7 at his home in London. His friend John of Antwerp helped with his last wishes. Holbein's grave location is not known.

Holbein's Art

What Influenced Holbein?

Holbein's first teacher was his father, Hans Holbein the Elder. His father was a skilled religious artist and portrait painter. The young Holbein learned his skills in his father's workshop in Augsburg. This city was known for its book trade, where woodcuts and engravings were popular. Holbein learned the older "Late Gothic" style, which focused on realism and clear lines. This style stayed with him throughout his life. In Basel, he was supported by smart thinkers called humanists. Their ideas helped shape his art.

During his time in Switzerland, Holbein might have visited Italy. He added Italian elements to his art. Experts notice the influence of Leonardo da Vinci's "sfumato" (smoky) technique in his work. From the Italians, Holbein learned how to use perspective and ancient designs. Even though he learned Italian techniques and new religious ideas, Holbein's art still kept many parts of the Gothic tradition.

His portrait style was different from the softer style of Titian. It was also different from the "Mannerism" style of William Scrots, who took over as King's Painter after Holbein. Holbein's portraits, especially his drawings, were more like those of Jean Clouet. He might have seen Clouet's work during his visit to France in 1524. He used Clouet's method of drawing with colored chalks on plain paper. During his second stay in England, Holbein learned the art of "limning," which was used for miniature portraits. In his last years, he made the portrait miniature a brilliant art form.

Religious Artworks

Holbein followed artists like his father who made a living from religious paintings. In the late 1400s, the church was still very traditional. But the growing Reformation movement, led by thinkers like Erasmus, began to change religious views. Basel became a main center for these new ideas.

Holbein's work shows this slow change from traditional to reformed religion. His painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1522) shows a human view of Christ. The Dance of Death (1523–26) is a series of woodcuts. It shows "Death" appearing to people from all walks of life. No one escapes Death, not even religious people. This series was a satire (a funny criticism) of the time.

Holbein also created Icones (illustrations of the Old Testament). These woodcuts were used in Bibles and other religious books. Some of Holbein's woodcuts even appeared in a recently found Bible by Michel De Villeneuve.

Holbein painted many large religious works between 1520 and 1526. These include the Oberried Altarpiece and the Solothurn Madonna. But when Basel's reformers started destroying religious images in the late 1520s, Holbein's work and income from religious art suffered.

He continued to make religious art, but on a smaller scale. In England, he designed funny religious woodcuts. His small painting for private prayer, Noli Me Tangere, shows his personal faith. It shows the moment when the risen Christ tells Mary Magdalene not to touch him.

Holbein is called "the best artist of the German Reformation." But his position was often unclear. He worked with Erasmus and More, but he also supported the changes started by Martin Luther. Luther wanted a return to the Bible and an end to the Pope's power. Holbein's woodcuts, like Christ as the Light of the World, showed Luther's attacks on Rome. Yet, he still worked for traditional religious people. After returning to Basel in 1528, he worked on both Jakob Meyer's Madonna and the Town Hall murals. The Madonna was a traditional religious image, while the Old Testament murals showed new reform ideas.

Holbein returned to England in 1532, just as Thomas Cromwell was changing religious groups there. Holbein soon worked for Cromwell's team, creating images to support the King's power over the church. During the time when monasteries were being closed, he made woodcuts where bad guys from the Bible looked like monks. His painting The Old and the New Law showed the Old Testament as the "Old Religion." Scholars have found hidden religious meanings in his portraits. In The Ambassadors, for example, the Lutheran hymn book and the crucifix hint at the religious situation of the time. Holbein painted few religious images later in his career. He focused on designs for objects and on simple portraits.

Amazing Portraits

For Holbein, "everything began with a drawing." He was a very skilled artist who could draw precise lines. Holbein's chalk and ink portraits show how good he was at drawing outlines. He always made drawings of the people he was going to paint. Many of these drawings still exist, even if the painted version is lost. This suggests some drawings were made just for their own beauty.

Holbein painted most of his portraits during his two times in England. In his first visit (1526–1528), he used colored chalks on plain paper for his drawings. In his second visit (1532 until his death), he drew on smaller pink-colored paper. He added ink to his chalk drawings. Holbein could draw these portraits quickly. Some experts think he used a special tool to help him trace the faces. His later drawings used fewer, stronger lines, but they were never boring. He was so good at showing space that every portrait, even simple ones, made the person feel real.

Holbein's painted portraits were based closely on his drawings. He would transfer the drawing to a wooden panel using tools. Then, he would build up the painting with tempera and oil paints. He captured every tiny detail, like each stitch on a costume. The result was a brilliant style where the people look very real and individual. Their clothes are painted with amazing detail, which helps us understand Tudor fashion.

People have different opinions about Holbein's precise portraits. Some see deep feelings in the people's faces. Others find them sad or distant. One writer said, "Perhaps a coolness fills their faces, but behind this calm lies a deep inner life." Some critics think his later, simpler portraits were a step backward. But other experts believe Holbein's skill never lessened.

Until the late 1530s, Holbein often put his subjects in a detailed setting. He sometimes included references to classical stories or the Bible. He also added curtains, buildings, and symbolic objects. These portraits showed off Holbein's skill and hinted at the person's private world. For example, his 1532 portrait of Sir Brian Tuke suggests Tuke's poor health. The symbols on Tuke's crucifix were meant to protect him from illness. Holbein painted the merchant Georg Gisze with many symbols of science and wealth. However, some of his other portraits of merchants focused more on the natural look of the face. This showed the simpler style Holbein would use later.

Experts now look for the fine details and quality to tell true Holbein paintings from copies. A key sign of Holbein's art is his careful and perfect approach. This can be seen in the changes he made to his portraits.

Tiny Miniatures

In his last ten years, Holbein painted many miniatures. These are small portraits, like tiny jewels, worn by people. His miniature technique came from the medieval art of decorating books. Holbein's larger paintings always had a miniature-like precision. He used this skill for the smaller form, making them feel grand even though they were tiny. The dozen or so known miniatures by Holbein show his mastery of "limning," as the technique was called.

His miniature portrait of Jane Small is considered a masterpiece. It has a rich blue background and clear outlines. An art expert said Holbein "portrays a young woman whose plainness is scarcely relieved by her simple costume... and yet there can be no doubt that this is one of the great portraits of the world."

Creative Designs

Throughout his life, Holbein designed both large murals and smaller objects. These included plates and jewelry. Often, his designs are the only proof that these works existed. For example, his murals for houses in Lucerne and Basel are only known through his drawings. As he got older, he added Italian Renaissance designs to his older Gothic style.

Many detailed designs on Greenwich armour, including King Henry's own armor, were based on Holbein's ideas. His style influenced English armor for almost 50 years after he died.

Holbein's drawing for the large Tudor wall painting at Whitehall shows how he prepared for big murals. It was made from 25 pieces of paper, with each figure cut out and glued onto the background. Many of Holbein's designs for glass paintings, metalwork, jewelry, and weapons also survive. They all show how precise and smooth his drawings were.

Holbein would sketch his ideas first, then draw more detailed versions. His final drawing was a perfect presentation. He often used traditional patterns for details like leaves. When designing valuable objects, Holbein worked closely with skilled workers like goldsmiths. His design work gave him a great understanding of different materials. This also helped him connect objects to the faces and personalities in his portraits.

Holbein's Lasting Impact

Holbein's fame is partly because of the famous people he painted. Many of his portraits have become well-known images. He created the standard image of Henry VIII. While he painted Henry as a hero, he also subtly showed the King's strong personality. Holbein's portraits of other historical figures, like Erasmus, Thomas More, and Thomas Cromwell, have shaped how we see them today. The same is true for many English lords and ladies whose looks are known only through his art. Because of this, one expert called Holbein "the cameraman of Tudor history." In Germany, Holbein is seen as an artist of the Reformation. In Europe, he is known for humanism.

In Basel, Holbein's friend Amerbach and his son collected his work. This collection later became the main part of the Holbein collection at the Kunstmuseum Basel. Even though Holbein's art was valued in England, few English documents from the 1500s mention him. The miniature artist Nicholas Hilliard said he always copied Holbein's style, calling it the best. The first full book about Holbein's life was written in 1604, but it had many mistakes.

Holbein's followers made copies of his work, but he didn't really start a "school" of art. One writer called him a "one-off" in art history. The only artist who seemed to use his techniques was John Bettes the Elder. His painting Man in a Black Cap (1545) is very similar to Holbein's style. Experts disagree on how much Holbein influenced English art. Some say he had no real followers in England. They point out the big difference between his detailed portraits and the more styled portraits of Elizabeth I.

However, "modern" painting in England might be said to have started with Holbein. Later artists knew his work. For example, Hans Eworth made copies of Holbein's Henry VIII painting. He even included a Holbein painting in the background of his own work. Holbein's influence on English portrait painting was huge. Thanks to him, a type of portrait was created that met the needs of the people being painted and raised English portraiture to a European level. It became the model for English court portraits during the Renaissance.

After the 1620s, there was a demand for "Old Masters" in England, led by Thomas Howard. Famous Flemish artists like Anthony van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens learned about Holbein through Arundel. Arundel ordered engravings of his Holbein paintings. From this time, Holbein's art was also valued in the Netherlands. The first detailed list of Holbein's works was made in 1656.

In the 1700s, Holbein became popular in Europe. People liked his precise art as a change from the more dramatic Baroque style. In England, Horace Walpole praised him as a master of the Gothic style. Walpole decorated his house with copies of Holbein's works and had a "Holbein room." Around 1780, people started to appreciate Holbein more. He became known as one of the great masters.

Later, a debate called the "Holbein dispute" happened in the 1870s. It turned out that a famous painting, the Meyer Madonna in Dresden, was a copy. The less-known version in Darmstadt was the real Holbein original. Since then, experts have removed Holbein's name from many copies. Today, scholars see Holbein as a very versatile artist. He was not just a painter, but also a great draftsman, printmaker, and designer.

Gallery

-

The Humiliation of the Emperor Valerian by the Persian King Shapur, c. 1521.

-

Noli me tangere, possibly 1524–26.

-

Portrait of Jane Seymour, around 1537.

-

Henry VIII and Henry VII, part of a drawing for a wall-painting at Whitehall, 1537.

-

Portrait of Anne of Cleves, around 1539.

-

Henry Brandon, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, miniature portrait, 1541.

-

Margaret Roper; around 1535–36.

See also

In Spanish: Hans Holbein el Joven para niños

In Spanish: Hans Holbein el Joven para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |