Thomas More facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas More

|

|

|---|---|

Sir Thomas More (1527)

by Hans Holbein the Younger |

|

| Lord Chancellor | |

| In office October 1529 – May 1532 |

|

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Wolsey |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

| In office 31 December 1525 – 3 November 1529 |

|

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Richard Wingfield |

| Succeeded by | William FitzWilliam |

| Speaker of the House of Commons | |

| In office 15 April 1523 – 13 August 1523 |

|

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Nevill |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 February 1478 City of London, England |

| Died | 6 July 1535 (aged 57) Tower Hill, London, England |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John |

| Parents | Sir John More Agnes Graunger |

| Education | University of Oxford Lincoln's Inn |

| Signature |  |

|

Philosophy career |

|

|

Notable work

|

Utopia (1516) Responsio ad Lutherum (1523) A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation (1553) |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy 16th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy, Catholic |

| School | Christian humanism Renaissance humanism |

|

Main interests

|

Social philosophy Criticism of Protestantism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Utopia |

|

Influenced

|

|

Sir Thomas More (born 7 February 1478 – died 6 July 1535) was an important English lawyer, judge, writer, and statesman. He is also known as Saint Thomas More in the Catholic Church. He was a key figure during the Renaissance, a time of great change and new ideas.

More served as the Lord Chancellor of England for Henry VIII from 1529 to 1532. He is famous for writing Utopia in 1516. This book describes an imaginary island with a perfect political system.

He strongly disagreed with the Protestant Reformation, a movement that challenged the Catholic Church. He also opposed King Henry VIII's decision to break away from the Catholic Church. More refused to accept Henry as the head of the Church of England. Because of this, he was found guilty of treason and executed. He is said to have famously declared: "I die the King's good servant, and God's first."

In 1935, Pope Pius XI made Thomas More a saint, recognizing him as a martyr. Later, in 2000, Pope John Paul II named him the patron saint of statesmen and politicians.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas More was born in London on 7 February 1478. His father, Sir John More, was a successful lawyer and later became a judge. Thomas was the second of six children.

He went to St. Anthony's School, which was one of the best schools in London at the time. From 1490 to 1492, he worked as a page for John Morton, who was the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England.

Morton was very supportive of new ways of thinking, known as "humanism." He saw great potential in young Thomas and helped him get into the University of Oxford in 1492. There, More studied classical subjects like Latin and Greek.

After two years, his father asked him to leave Oxford to start training as a lawyer in London. He first studied at New Inn and then at Lincoln's Inn. By 1502, he became a qualified lawyer.

Spiritual Journey

His friend, the famous scholar Erasmus, said that Thomas More once thought about becoming a monk. Between 1503 and 1504, More lived near a monastery in London. He joined the monks in their spiritual practices.

Even though he admired their devotion, More decided to remain a regular person. He was elected to Parliament in 1504 and got married the next year.

More continued to practice spiritual self-discipline throughout his life. For example, he sometimes wore a hair shirt close to his skin.

Family Life

Thomas More married Jane Colt in 1505. They lived in a house in London for almost 20 years before moving to Chelsea in 1525. Erasmus mentioned that More wanted to give his wife a better education than she had before. He taught her music and literature.

Thomas and Jane had four children: Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John. Sadly, Jane died in 1511.

Within a month, More married Alice Middleton, a widow. He chose her to manage his home and care for his young children. This quick marriage was unusual, but More easily got special permission for it.

More did not have children with Alice, but he raised her daughter from her previous marriage as his own. He also became the guardian of two other young girls. One of them, Anne Cresacre, later married his son, John More. The other, Margaret Giggs, was the only family member to see his execution.

More was a loving father. He wrote letters to his children when he was away and encouraged them to write back often.

Daughters' Education

More believed his daughters should have the same classical education as his son. This was very unusual for the time. His oldest daughter, Margaret, was especially admired for her learning. She was very good at Greek and Latin.

In 1522, More proudly told a bishop about a letter Margaret had written. The bishop was amazed by her excellent Latin and deep thoughts. He even sent her a gold coin as a sign of his respect.

More's decision to educate his daughters inspired other noble families. Even Erasmus, who was initially unsure, became very impressed by their achievements.

A painting of More and his family by Holbein was lost in a fire. However, a copy was made, and two versions of it still exist today.

Political Career

In 1504, More was elected to Parliament to represent Great Yarmouth. In 1510, he began representing London.

From 1510, More worked as an undersheriff for the City of London. This was an important job where he became known as an honest and effective public servant. In 1514, he became a Master of Requests and a Privy Counsellor.

After a diplomatic trip with Thomas Wolsey to Calais and Bruges, More was knighted in 1521. He also became the under-treasurer of the Exchequer, which managed the country's money.

As a secretary and personal adviser to King Henry VIII, More became very important. He welcomed foreign diplomats, wrote official papers, and helped the King communicate with Lord Chancellor Wolsey. More also served as a High Steward for the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

In 1523, More was elected as a Member of Parliament for Middlesex. The House of Commons then chose him to be their Speaker. In 1525, More became the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, overseeing parts of northern England.

Becoming Lord Chancellor

After Thomas Wolsey lost his position, Thomas More became the Lord Chancellor in 1529. He was known for handling legal cases very quickly.

Standing Against the Reformation

More strongly supported the Catholic Church. He saw the Protestant Reformation as a dangerous challenge to the unity of both the church and society.

He worked to stop Protestant books from entering England. He also investigated and arrested people suspected of being Protestants, especially those who printed or shared Bibles and other materials from the Reformation. More also tried to stop Tyndale's English translation of the New Testament.

Resigning from His Role

The King and the Pope disagreed about who had more power. More firmly believed that the Pope was the head of the Church, not the King of England. In 1529, a law made it a crime to support any authority outside England (like the Pope) over the King.

In 1530, More refused to sign a letter asking Pope Clement VII to cancel Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon. He also argued with Henry VIII about laws against heresy. In 1531, a royal order required clergy to swear an oath recognizing the King as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Bishops agreed to sign, but only with the condition "as far as the law of Christ allows."

This was called the Submission of the Clergy. Cardinal John Fisher and some other clergy refused to sign. Henry removed many clergy who supported the Pope from important church positions. More continued to refuse the Oath of Supremacy and did not support the King's marriage annulment. However, he kept his opinions private and did not openly speak against the King.

On 16 May 1532, More resigned as Chancellor. His decision was influenced by the English Church's agreement to the King's demands the day before.

Arrest and Imprisonment

In 1533, More did not attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn as Queen. While this was not technically treason, it was seen as an insult to Anne. King Henry took action against him.

Soon after, More was accused of taking bribes, but these charges were dropped because there was no proof. In early 1534, Thomas Cromwell accused More of advising Elizabeth Barton, a nun who had spoken against the King's divorce. This was considered hiding treason.

More had met Barton and was impressed by her strong beliefs.

On 13 April 1534, More was asked to swear an oath to the Act of Succession. This oath would confirm Anne as queen and her children's right to the throne. More firmly refused to take the oath, which also recognized the King as the supreme head of the Church in England.

His enemies had enough evidence to have the King arrest him for treason. Four days later, Henry had More imprisoned in the Tower of London. While there, More wrote a spiritual book called A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation. Thomas Cromwell visited him several times, urging him to take the oath, but More continued to refuse.

Trial and Execution

More's trial took place on 1 July 1535. The judges included the new Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Audley, and members of Anne Boleyn's family. Norfolk offered More a chance to receive the King's "gracious pardon" if he changed his "obstinate opinion." More replied that he had not taken the oath, but he also had not spoken against it. He believed his silence should be accepted.

Thomas Cromwell, the King's most powerful adviser, brought in Richard Rich to say that More had denied the King was the rightful head of the Church. More said this testimony was false. Two other witnesses present denied hearing this conversation.

Despite the questionable testimony, the jury found More guilty in just fifteen minutes. He was sentenced to a harsh execution, but the King changed it to execution by beheading.

The execution happened on 6 July 1535, at Tower Hill. As he went up the steps to the scaffold, which looked shaky, More is said to have joked, "I pray you, master Lieutenant, see me safe up and [for] my coming down, let me shift for my self." On the scaffold, he famously declared, "that he died the king's good servant, and God's first." After he finished praying, the executioner asked for his forgiveness. More cheerfully kissed him and forgave him.

Writings and Letters

Thomas More was a great writer, especially of letters, like his friend Erasmus. Only a small part of his letters (about 280) have survived. These include personal letters, official government letters (mostly in English), letters to other scholars (in Latin), and letters to his children.

His "prison-letters" are especially famous. He exchanged these with his oldest daughter Margaret while he was waiting for his execution in the Tower of London.

More also wrote about spiritual topics. These include A Treatise on the Passion and De Tristitia Christi (The Agony of Christ). He wrote the last one by hand while imprisoned in the Tower. This manuscript was saved and is now in a museum in Valencia, Spain.

Honored as a Saint

| Saint Thomas More |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Saint Thomas More, executed on Tower Hill (London) in 1535, apparently based on the Holbein portrait.

|

|

| Reformation Martyr, Scholar | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion |

| Beatified | 29 December 1886, Florence, Kingdom of Italy, by Pope Leo XIII |

| Canonized | 19 May 1935, Vatican City, by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | Church of St Peter ad Vincula, London, England |

| Feast | 22 June (Catholic Church) 6 July (Church of England) 9 July (Catholic Extraordinary Form) |

| Attributes | dressed in the robe of the Chancellor and wearing the Collar of Esses; axe |

| Patronage | Statesmen and politicians; lawyers; Ateneo de Manila Law School; Diocese of Arlington; Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee; Kerala Catholic Youth Movement; University of Malta; University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Arts and Letters |

In the Catholic Church

Pope Leo XIII declared Thomas More and John Fisher "blessed" (a step towards sainthood) in 1886. Then, Pope Pius XI made them saints in 1935. More's feast day is celebrated on 22 June (with St John Fisher) or 9 July.

On 31 October 2000, Pope John Paul II declared More the "heavenly Patron of Statesmen and Politicians."

In the Anglican Church

In 1980, the Church of England added More and Fisher to their calendar of "Saints and Heroes of the Christian Church." They are remembered every 6 July (the day More was executed) as "Thomas More, scholar, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, Reformation Martyrs, 1535." This remembrance is recognized by all Anglican Churches around the world.

The popular play and film A Man for All Seasons helped make More famous. It showed him as someone who stood up for his beliefs and conscience.

Lasting Impact

More's strong beliefs and courage during his imprisonment, trial, and execution greatly added to his fame, especially among Catholics. His friend Erasmus described More's character as "purer than any snow" and his genius as unmatched in England. When Emperor Charles V heard of More's execution, he said he would rather have lost a major city than such a valuable adviser.

Many famous people have praised Thomas More. G. K. Chesterton thought he might be the greatest Englishman. Jonathan Swift called him "a person of the greatest virtue this kingdom ever produced."

Some scholars believe More used humor and irony in his book Utopia. They see it as a critique of society at the time. In 2002, More was ranked number 37 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

In Books and Movies

William Roper wrote one of the first biographies of More in modern English.

Sir Thomas More is a play from around 1592, partly written by William Shakespeare. It shows More as a wise and honest leader.

The 1960 play A Man for All Seasons by Robert Bolt portrays Thomas More as a tragic hero. The title comes from a quote describing More as "a man for all seasons," meaning he was good for all times and situations.

The play was made into a film in 1966, directed by Fred Zinnemann. It starred Paul Scofield, who won an Oscar for his role as More. The film also won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

In the 1969 film Anne of the Thousand Days, More is played by William Squire.

The novelist Hilary Mantel wrote a trilogy of books (Wolf Hall, Bring Up the Bodies, and The Mirror and the Light) that show More from the perspective of Thomas Cromwell. In these books, More is shown as someone who persecuted Protestants.

The TV series The Tudors also shows More as a peaceful, devout Catholic family man. However, it also shows him hating Protestantism and burning books by Martin Luther. Some parts of this portrayal are not historically accurate, like showing him at executions of heretics, which he did not attend.

Places Connected to Thomas More

Westminster Hall

A plaque in Westminster Hall in London remembers More's trial for treason. This building, where Parliament meets, was well known to More, who served there before becoming Lord Chancellor.

Beaufort House

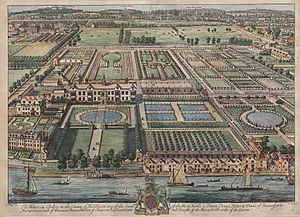

More bought land in Chelsea around 1520 to build his home. It was convenient because it was between the King's palaces along the River Thames. He built a grand red-brick house, known as More's house or Chelsea House, where he lived until his arrest in 1534.

After his arrest, the King took his estate. In 1682, the property was renamed Beaufort House.

Crosby Hall

In 1523, More bought Crosby Place in London. He sold it to his friend Antonio Bonvisi eight months later, never having lived there himself. Because of this, the King did not take this property after More's execution.

Chelsea Old Church

Next to Crosby Hall is Chelsea Old Church. More paid for the southern chapel of this church and sang with the choir there. Most of the church was destroyed in World War II but was rebuilt in 1958.

Inside, there is a tomb and epitaph (a message on a tombstone) that More built for himself and his wives. It describes his life and achievements. More is not buried here, but some of his family might be. Outside the church, there is a statue of More from 1969, honoring him as a "saint," "scholar," and "statesman."

Tower Hill

A plaque and a small garden at Tower Hill, outside the Tower of London, remember the execution site. Many people, including Thomas More, were executed here as religious martyrs or prisoners of conscience. More's body was buried in an unmarked grave inside the Royal Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula, within the Tower walls.

St Katharine Docks

Thomas More is remembered by a stone plaque near St Katharine Docks, just east of the Tower. The street there is now named Thomas More Street in his honor.

St Dunstan's Church, Canterbury

St Dunstan's Church in Canterbury is believed to hold More's head. His daughter, Margaret Roper, rescued it, and her family lived near this church. A stone near the altar marks the Roper family vault. The church has investigated this burial vault, and displays show the findings.

Main Works by Thomas More

- A Merry Jest (around 1516)

- Utopia (1516) - His most famous work, describing an ideal society.

- Latin Poems (1518, 1520)

- Responsio ad Lutherum (The Answer to Luther, 1523)

- A Dialogue Concerning Heresies (1529, 1530)

- Supplication of Souls (1529)

- The Confutation of Tyndale's Answer (1532, 1533)

- Apology (1533)

- A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation (written 1534, published later) - A book he wrote while imprisoned.

- De Tristitia Christi (The Agony of Christ, written 1535, published later) - Another spiritual work written in the Tower of London.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tomás Moro para niños

In Spanish: Tomás Moro para niños