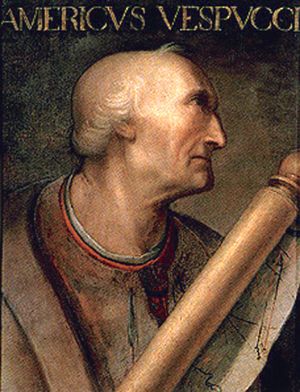

Amerigo Vespucci facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Amerigo Vespucci

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 9 March 1454 Florence, Republic of Florence

|

| Died | 22 February 1512 (aged 57) |

| Other names | Américo Vespucio (Spanish) Americus Vespucius (Latin) Américo Vespúcio (Portuguese) |

| Occupation | Merchant, explorer, cartographer |

| Known for | Demonstrating to Europeans that the New World was not Asia but a previously unknown fourth continent, Being whom the Americas are named after. |

| Signature | |

|

|

Amerigo Vespucci was an Italian explorer and navigator. He lived from 1454 to 1512. The name "America" comes from his name. He helped Europeans understand that the lands found by Columbus were a new continent, not part of Asia.

Contents

Amerigo Vespucci's Early Life and Education

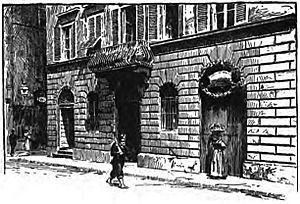

Amerigo Vespucci was born in Florence, Italy, on March 9, 1454. Florence was a rich city known for its art and learning during the Renaissance. He was the third son of Nastagio Vespucci, who worked as a notary (a legal official).

Amerigo was taught by his uncle, Giorgio Antonio Vespucci. His uncle was a famous scholar in Florence. He gave young Amerigo a good education in literature, philosophy, and Latin. Amerigo also learned about geography and astronomy. These subjects became very important later in his life.

Vespucci Family Connections

Vespucci's family was not super rich, but they had good political connections. His grandfather, also named Amerigo Vespucci, worked for the Florentine government for 36 years. His father, Nastagio, also held government positions. The Vespucci family was close to Lorenzo de' Medici, who was a powerful ruler in Florence.

Amerigo had two older brothers. Antonio became a notary like his father. Girolamo joined the Church and became a Knight Hospitaller.

Vespucci's Early Career and Move to Seville

Amerigo worked with his father for a while and continued his studies. In 1482, after his father died, Amerigo started working for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici. He began as a household manager. Over time, he took on more important tasks, handling business for the family in Florence and other places. He was always interested in geography. He even bought an expensive map from a famous mapmaker named Gabriel de Vallseca.

Life in Seville

By 1492, Vespucci had moved to Seville, Spain, permanently. It's not clear why he left Florence. In Seville, he married a Spanish woman named Maria Cerezo. We don't know much about her, but Vespucci's will says she was the daughter of a famous military leader.

Amerigo Vespucci's Famous Letters

Most of what we know about Vespucci's voyages comes from letters believed to be written by him. Two of these letters were published while he was alive. They became very popular in Europe. Some experts now think that Vespucci might not have written these two published letters exactly as they appeared. They might have been changed or based on his real letters.

- Mundus Novus (1503): This letter was written to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, who was Vespucci's friend and supporter. It was first published in Latin. The letter described his trip to Brazil in 1501–1502, when he was sailing for Portugal. This letter was very popular. Within a year, it was printed 12 times and translated into many languages. By 1550, there were at least 50 editions.

- Letter to Soderini (1505): This letter was sent to Piero di Tommaso Soderini, the leader of Florence. It was written in Italian and published around 1505. This letter is more exciting and is the only one that says Vespucci made four voyages. Many historians question if Vespucci really wrote this letter and if everything in it is true. However, this document was the main reason why the American continent was named after Amerigo Vespucci.

Other letters were found much later, more than 250 years after Vespucci died. Most historians now agree that these letters were written by Vespucci, but some parts are still debated.

- Letter from Seville (1500): This letter describes a voyage he made in 1499–1500 for Spain. It was first published in 1745.

- Letter from Cape Verde (1501): This letter was written in Cape Verde at the start of a voyage for Portugal in 1501–1502. It describes the first part of the trip from Lisbon to Cape Verde.

- Letter from Lisbon (1502): This letter continues the story from the Cape Verde letter. It describes the rest of the 1501–1502 voyage for Portugal.

- Ridolfi Fragment (1502): This is part of a letter believed to be from Vespucci. It seems to be a reply to questions from someone else. It mentions three voyages by Vespucci: two for Spain and one for Portugal.

Amerigo Vespucci's Voyages

The exact number of Vespucci's voyages and their routes have been debated for a long time.

The Disputed Voyage of 1497–1498

This is the most debated of Vespucci's voyages. The only proof of it is a letter from 1504. The letter says Vespucci left Spain on May 10, 1497, and returned on October 15, 1498.

Some scholars believe this letter is not real. The story in it has many inconsistencies, especially about the route. It's possible that Vespucci made up this account using details from his later trips. He might have wanted to seem like the first European to reach the mainland of the New World. Some historians think someone else wrote the letter, using information from Vespucci's private letters about his 1499 and 1501 trips, which do not mention a 1497 voyage.

The Voyage of 1499–1500

In 1499, Vespucci joined a Spanish expedition. It was led by Alonso de Ojeda, with Juan de la Cosa as the main navigator. Their goal was to explore the coast of a new land that Columbus had found. They especially wanted to find a rich source of pearls. Vespucci and his partners paid for two of the four ships.

Vespucci's exact role on this trip is not clear. He later wrote as if he was a leader, but this is unlikely because he was not very experienced. He might have been a business representative for the investors. Years later, Ojeda said that "Morigo Vespuche" was one of his pilots.

The ships left Spain on May 18, 1499. They stopped in the Canary Islands before reaching South America. They landed somewhere near modern-day Suriname or French Guiana. From there, the fleet split up. Ojeda went northwest towards modern Venezuela. Vespucci went south with the other two ships. Vespucci's account is the only record of this southbound journey. He thought they were on the coast of Asia. He hoped that by going south, they would reach the Indian Ocean.

They passed two huge rivers, the Amazon and the Para. These rivers poured fresh water far out into the sea. They continued south for about 150 miles. Then, they met a very strong current that they could not overcome. They had to turn around and go back north to where they first landed. From there, Vespucci continued up the South American coast to the Gulf of Paria and along the shore of what is now Venezuela. They might have met up with Ojeda again, but it's not certain. In late summer, they decided to go north to the Spanish colony at Hispaniola in the West Indies. They needed to resupply and repair their ships before going home. After Hispaniola, they briefly raided the Bahamas for slaves, capturing 232 natives. Then, they returned to Spain.

The Voyage of 1501–1502

In 1501, Manuel I of Portugal asked for an expedition. He wanted to explore a large landmass far to the west in the Atlantic Ocean. This land had been found by chance by Pedro Álvares Cabral on his way to India. This land would later become Brazil. The king wanted to know how big this new land was and where it was located compared to the line set by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Any land east of that line belonged to Portugal. Vespucci was known as a good explorer and navigator. The king hired him to be a pilot under the command of Gonçalo Coelho.

Coelho's fleet of three ships left Lisbon in May 1501. They resupplied at Cape Verde before crossing the Atlantic. Coelho left Cape Verde in June. From this point, Vespucci's account is the only record of their explorations. On August 17, 1501, the expedition reached Brazil. When they landed, they met hostile natives who killed one of their crew members. Sailing south along the coast, they found friendlier natives and traded with them. At 23° South, they found a bay. They named it Rio de Janeiro because it was January 1, 1502. On February 13, 1502, they left the coast to return home. Vespucci estimated their latitude at 32° South, but experts now think they were closer to 25° South. Their journey home is not clear because Vespucci's records of observations and distances are confusing.

The Possible Voyage of 1503–1504

In 1503, Vespucci might have joined a second expedition for Portugal. This trip would have explored the east coast of Brazil again. There is some evidence that Coelho led a voyage around this time. However, it's impossible to know if Vespucci was part of it. The only source for this last voyage is the Soderini letter. But, as mentioned, many modern scholars doubt that Vespucci wrote that letter. So, it's uncertain if Vespucci made this trip.

Vespucci's Later Years and Death

By early 1505, Vespucci was back in Seville. His reputation as an explorer continued to grow. His recent work for Portugal did not hurt his standing with King Ferdinand of Spain. In fact, the king was probably interested in learning about a possible western route to India. In February, the king called him to discuss navigation. Over the next few months, he received payments from the crown. In April, the king declared him a citizen of Castile and León.

From 1505 until his death in 1512, Vespucci worked for the Spanish crown. He continued to supply ships heading to the Indies. He was also hired to captain a ship for a trip to the "spice islands," but that voyage never happened. In March 1508, he was named chief pilot for the Casa de Contratación, or House of Commerce. This was a main trading center for Spain's lands overseas. He earned a good salary. In his new role, Vespucci made sure that ship pilots were well-trained and licensed before sailing to the New World. He also had to create a "model map" using information from pilots after each voyage.

Vespucci wrote his will in April 1511. He left most of his property, including five household slaves, to his wife. His clothes, books, and navigation tools went to his nephew, Giovanni Vespucci. He asked to be buried in his wife's family tomb. Vespucci died on February 22, 1512, at age 57.

After his death, Vespucci's wife received a yearly payment. His nephew Giovanni was hired into the Casa de Contratación. He spent his later years secretly gathering information for Florence.

How America Got Its Name

Vespucci's voyages became widely known in Europe after two accounts, believed to be from him, were published between 1503 and 1505. In 1506, the Soderini letter (1505) was read by a group of French scholars. They thought that Vespucci had discovered a new continent.

In April 1507, Matthias Ringmann and Martin Waldseemüller published their book Introduction to Cosmography with a world map. The book was in Latin and included a Latin translation of the Soderini letter. In the introduction to the letter, Ringmann wrote:

I see no reason why anyone could properly disapprove of a name derived from that of Amerigo, the discoverer, a man of sagacious genius. A suitable form would be Amerige, meaning Land of Amerigo, or America, since Europe and Asia have received women's names.

A thousand copies of the world map were printed. Its title was Universal Geography According to the Tradition of Ptolemy and the Contributions of Amerigo Vespucci and Others. It had large portraits of Ptolemy and Vespucci. For the first time, the name America was used on a map of the New World.

The Introduction and map were very successful. Four editions were printed in the first year. The map was used in universities and was popular among mapmakers. In the years that followed, other maps were printed that often used the name America. In 1538, Gerardus Mercator used America to name both the North and South continents on his important map. By this time, the name was firmly set for the New World.

Many supporters of Columbus felt that Vespucci had taken an honor that belonged to Columbus. Most historians now believe that Vespucci did not know about Waldseemüller's map before he died in 1512. Many also say that he was not even the author of the Soderini letter.

Amerigo Vespucci's Legacy

Vespucci is better known for his letters (whether he wrote them all or not) than for his discoveries. The naming of America after him shows how important he was in exploring the New World. He also played a big role in making Europeans aware of these newly discovered continents.

See also

In Spanish: Américo Vespucio para niños

In Spanish: Américo Vespucio para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |