Gerardus Mercator facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gerardus Mercator

|

|

|---|---|

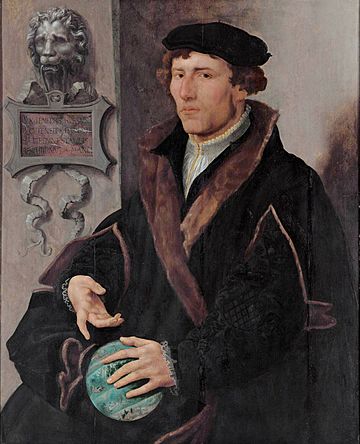

Portrait by the workshop of Titian, c. 1550

|

|

| Born |

Geert de Kremer

5 March 1512 Rupelmonde, County of Flanders

|

| Died | 2 December 1594 (aged 82) Duisburg, United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Education | University of Leuven |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Barbara Schellekens

(m. 1534; died 1586)Gertrude Vierlings

(m. 1589) |

| Children | 6, including Arnold and Rumold |

| Scientific career | |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

| Signature | |

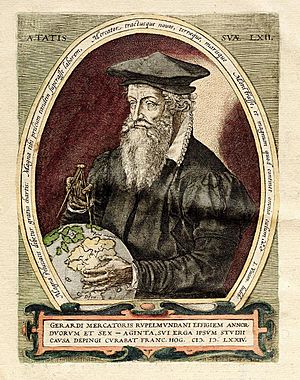

Gerardus Mercator (born Geert de Kremer; 5 March 1512 – 2 December 1594) was a famous Flemish geographer and mapmaker. He is best known for creating a special world map in 1569. This map used a new way of drawing the Earth, called the Mercator projection. It made sailing routes (called rhumb lines) appear as straight lines, which was a huge help for sailors. Even today, this method is used for sea charts.

Mercator was a very important person in the history of mapmaking. He is seen as one of the founders of the Netherlandish school of mapmaking, along with Gemma Frisius and Abraham Ortelius. He was also known for making globes and scientific tools. Besides maps, he was interested in many subjects like history, math, and even the Earth's magnetic field. He was also a skilled engraver and calligrapher.

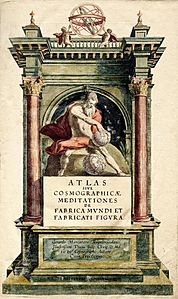

Unlike many scholars of his time, Mercator didn't travel much. He learned about geography from his huge library of over a thousand books and maps. He also learned from visitors and from writing letters (in six languages!) to other scholars, leaders, travelers, and sailors. His early maps were large, meant for hanging on walls. But later in life, he made over 100 smaller maps that could be put together in a book. This book, published in 1595, was the first time the word "Atlas" was used for a collection of maps. Mercator chose this name to honor the Titan Atlas, a mythical king he believed was the first great geographer.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Flanders

Gerardus Mercator was born Geert de Kremer in a small village called Rupelmonde, in Flanders (part of modern-day Belgium). He was the seventh child of Hubert and Emerance de Kremer. His parents were from Germany, but they were visiting his uncle, Gisbert de Kremer, who was an important priest in Rupelmonde.

When Geert was six, his family moved back to Rupelmonde. He went to the local school there, learning reading, writing, math, and Latin.

School Days in 's-Hertogenbosch

After his father died in 1526, his uncle Gisbert became his guardian. Gisbert hoped Geert would become a priest. So, at age 15, Geert was sent to a famous school in 's-Hertogenbosch. This school was known for its focus on studying the Bible and questioning old church rules. This way of thinking would cause Mercator problems later in his life.

At this school, Geert studied the Bible, Latin, logic, and famous ancient writings like those of Aristotle and Ptolemy. All lessons were in Latin. It was here that he changed his name to Gerardus Mercator Rupelmundanus. "Mercator" is the Latin word for "merchant," which was his family name, Kremer. The school was also famous for its beautiful handwriting, which might be where Mercator learned the elegant italic script he used in his maps.

University of Leuven

In 1530, Mercator went to the famous University of Leuven. He was a poor student but became friends with other students who would later become famous, like the doctor Andreas Vesalius and the statesman Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle.

At the university, he studied philosophy, theology, and Greek. He also learned math, geometry, and astronomy, but these subjects were not as important as theology back then. Mercator finished his studies in 1532.

Doubts and a New Path

After university, Mercator faced a problem. He found contradictions between what he learned from the Bible and his own scientific observations, especially about how the world was created and described. Questioning these ideas was seen as dangerous at the university.

He left Leuven for Antwerp to think about philosophy. During this time, he met a friar named Franciscus Monachus. Monachus also questioned old ideas about geography and based his views on careful study and observation. Mercator was very impressed by Monachus's map collection and a famous globe he had made. These meetings probably inspired Mercator to focus on geography. He later said, "Since my youth, geography has been for me the primary subject of study."

Becoming a Master Mapmaker

Learning from Gemma Frisius

Around 1534, Mercator returned to Leuven and began studying geography, math, and astronomy with Gemma Frisius. Gemma was only four years older but was a brilliant teacher. Mercator quickly learned math and how to make scientific tools. He became skilled at working with brass, doing calculations, and engraving.

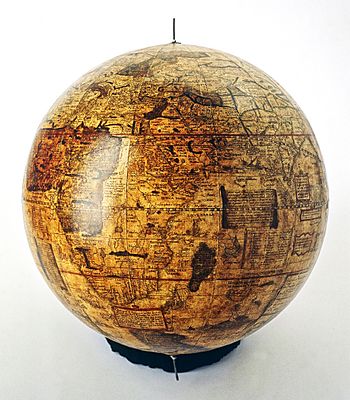

Gemma and another craftsman, Gaspar Van der Heyden, had made a globe in 1529. By 1535, they planned a new one with the latest discoveries. Mercator helped engrave the text on this new globe, and his name appeared on it for the first time. The globe was finished in 1536, and a globe of the stars followed a year later. These globes were very popular and expensive, providing Mercator with income. In 1536, he married Barbara Schellekens, and their first child, Arnold, was born a year later.

Mercator's work on the globes brought him to the attention of important people, including the powerful Emperor Charles V. This connection helped him get commissions and support throughout his life.

Early Maps and Globes

Mercator quickly became very productive.

- In 1537, at just 25, he made a detailed map of the Holy Land. He researched, engraved, and printed it himself. This map showed the route of the Israelites from Egypt.

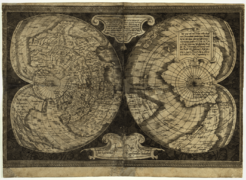

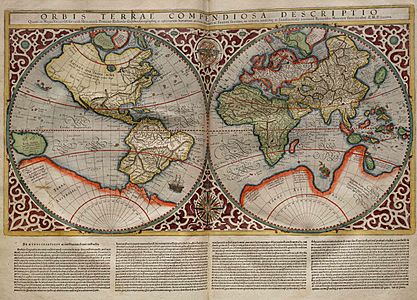

- A year later, in 1538, he created his first world map, called Orbis Imago. This was the first map to clearly show North and South America as separate continents.

- In 1539/40, he made a map of Flanders.

- In 1541, he produced a new terrestrial globe.

All these works were highly praised and sold well. Mercator dedicated his maps to important figures like Emperor Charles V, showing his growing influence. He also wrote a small book on how to write in the elegant italic script, which he used on all his maps.

Facing Challenges and Moving On

Trouble with Authorities

Mercator was a devout Christian, but he was born at a time when new ideas about Christianity were spreading, led by Martin Luther. Mercator never said he was a Lutheran, but he was sympathetic to some of their ideas. He studied the Bible deeply, which led to questions that some of his teachers considered dangerous.

In 1543, Mercator was accused of being a "heretic" (someone whose beliefs go against official church teachings). He was arrested in Rupelmonde and put in prison. No evidence was found against him, and his powerful friends spoke up for him. After seven months, he was released. This difficult experience likely influenced his decision to move.

Moving to Duisburg

In 1552, at age 40, Mercator moved from Leuven to Duisburg, in what is now Germany. He never fully explained why, but several reasons likely played a part:

- He could not be a full citizen in Leuven because he wasn't born in the region.

- The Catholic authorities in his home country were becoming very strict about religious differences.

- Duisburg was known for being more tolerant of different beliefs.

- A new university was planned in Duisburg, and Mercator hoped to teach there.

Duisburg was a peaceful town, and it became the perfect place for Mercator's talents to flourish. He quickly became a respected figure, known for his intellect, maps, and instruments. The local ruler, Duke Wilhelm, appointed him as his court "cosmographer," a title that meant he was an expert in geography, astronomy, and the history of the world.

Mercator even made a special pair of small globes for the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. The inner Earth globe was made of wood, and the outer celestial globe was made of engraved crystal glass with gold. These globes were designed to rotate on top of an astronomical clock.

Mercator also shared his ideas about magnetism, suggesting that compasses are attracted to a single magnetic pole. He even tried to calculate its position.

Major Achievements in Duisburg

The Great Map of Europe

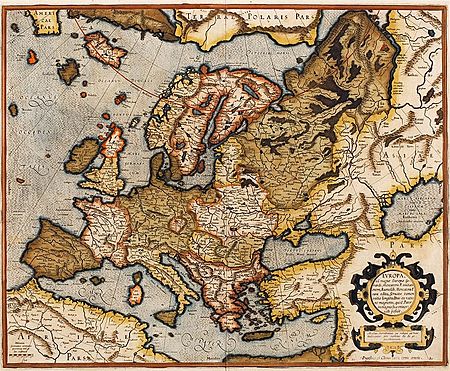

In 1554, Mercator published his long-awaited wall map of Europe. He had worked on it for over 12 years, gathering and comparing a huge amount of information. The result was a map with amazing detail and accuracy. It was praised by scholars everywhere and sold very well for many years.

Family and Collaborations

Mercator's sons grew up and joined his profession. His eldest son, Arnold, started making maps and later took over the family business. His third son, Rumold, worked in London, which helped Mercator get new information about discoveries from English explorers.

In 1564, Mercator published his map of Britain. This map was much more accurate than any before it. It was a politically sensitive map because it showed Catholic religious sites and left out Protestant ones. It was likely used as a guide for a planned invasion of England by Spain.

Mercator also took on a new challenge: surveying and mapping Lorraine. He traveled through difficult terrain with his son Bartholemew to collect the raw data. This trip was very hard on his health.

The Chronologia and Cosmographia

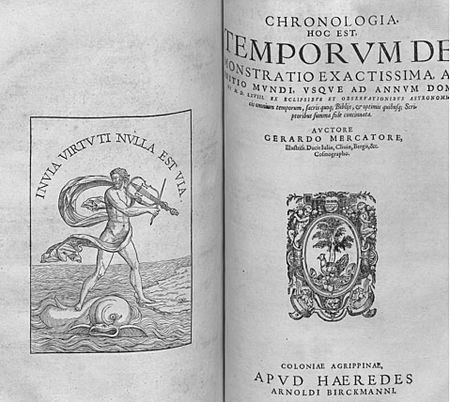

In 1569, Mercator published his Chronologia, a huge book listing all important events since the beginning of the world. He used the Bible and 123 other historical books to create it. He was the first to link historical dates of eclipses to mathematical calculations. This book was highly praised by scholars across Europe. However, the Catholic Church put it on their list of forbidden books because Mercator included information about Martin Luther.

The Chronologia was part of an even bigger project called Cosmographia, which was meant to describe the entire Universe. This grand plan included:

- The creation of the world.

- A description of the heavens (astronomy and astrology).

- A description of the Earth (modern and ancient geography).

- History of states.

- Chronology (which he had already completed).

The Famous Mercator Projection

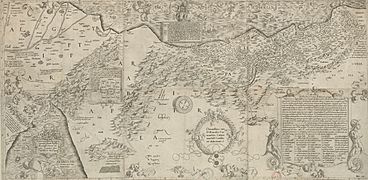

Also in 1569, Mercator published his most famous map: Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata (A new and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation). As explorers sailed the oceans, they needed better maps. Their old charts made their positions inaccurate after long voyages. Mercator's solution was to create a map where sailing courses of constant direction (rhumb lines) appeared as straight lines. This was revolutionary for navigation.

While the large wall map wasn't used on ships, the Mercator projection became the standard for marine charts worldwide within a hundred years. However, it distorts the size of landmasses at high latitudes (like Greenland looking much larger than it is), so it's not ideal for showing continents.

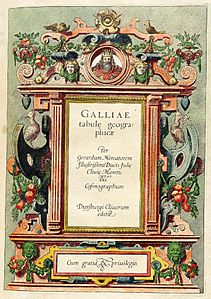

Ptolemy's Maps and the Atlas

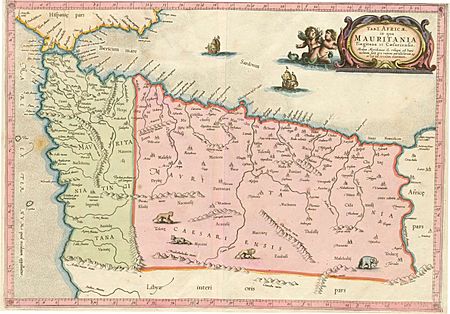

In 1578, Mercator published a new, improved version of Ptolemy's ancient maps. This was his way of honoring the ancient geographer who had inspired him. He carefully compared many old versions of Ptolemy's work to create the most accurate one.

By this time, his sons and grandsons were handling the practical work of making maps and globes. In 1585, he released a collection of 51 modern maps covering France, the Low Countries, and Germany. Sadly, his wife Barbara died in 1586, and his eldest son Arnold died the next year. This left only Rumold and Arnold's sons to continue the business.

In 1589, at 77, Mercator remarried Gertrude Vierlings. He also published a second collection of 22 maps covering Italy, Greece, and the Balkans. In the introduction to this collection, he mentioned Atlas, the mythical king, as his inspiration. A year later, Mercator had a stroke, which greatly weakened him. He worked with his family to finish his remaining maps and a new book on the Creation of the World. This last book was the culmination of his life's work. He died in 1594 after two more strokes.

Legacy

Mercator was buried in the church of St. Salvatore in Duisburg. His family quickly prepared his final work, the Atlas, for publication.

The full Atlas included all the maps from his previous collections, totaling 102 new maps by Mercator. His heirs added five introductory maps, including a world map by his son Rumold. This was the first time the word "Atlas" was used as the title for a collection of maps.

The Atlas wasn't an immediate success because it was incomplete (it didn't include Spain or detailed maps outside Europe). However, in 1604, Jodocus Hondius bought Mercator's copper plates. Hondius added many new maps and republished the Atlas under his own name, but he gave full credit to Mercator. Hondius was a great businessman, and under his guidance, the Atlas became a huge success. Many editions were published, making Mercator's maps widely known.

Mercator's greatest and most lasting legacy is the Mercator projection. His way of drawing maps, where constant sailing courses appear as straight lines, completely changed navigation, making it simpler and safer. While the projection is now less used for showing entire continents due to its distortions, it remains essential for nautical charts.

Mercator is honored in many ways today. There are statues of him in various cities, and his name is used for ships, buildings, and even an asteroid. On March 5, 2015, Google celebrated his 503rd birthday with a special Google Doodle.

There are two museums dedicated to Mercator:

- Kultur- und Stadthistorisches Museum, Duisburg, Germany.

- Mercator Museum (Stedelijke musea), Sint-Niklaas, Belgium.

Works

Globes and Instruments

- 1536 Gemma Frisius terrestrial globe. Mercator engraved the text for this globe, which was designed by Frisius.

- 1537 Gemma Frisius celestial globe. Mercator's name appeared equally with Frisius's on this globe of the stars.

- 1541/1551 Terrestrial and celestial globes. Mercator made these large globes. The terrestrial globe was special because it suggested that North America was separate from Asia. The celestial globe used the latest information from Copernicus. These globes were sold in large numbers.

Maps

- 1537 Holy Land map. Amplissima Terrae Sanctae descriptio ad utriusque Testamenti intelligentiam. (A description of the Holy Land for understanding both testaments.) This map showed the route of the Israelites.

- 1538 World Map (Orbis Imago). This was the first map to clearly show North and South America as separate continents.

- 1540 Flanders map. Flandria. This very accurate wall map was commissioned by merchants and dedicated to Emperor Charles V.

- 1554 Europe map. Europae descriptio. This large wall map was praised for its detail and accuracy.

- 1564 British Isles map. Anglia & Scotiae & Hibernie nova descriptio. This map was very accurate and showed Catholic religious sites.

- 1564 Lorraine map. A map commissioned by Duke René of Lorraine, which Mercator surveyed himself.

- 1569 World Map. Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata. This is Mercator's most famous map, introducing the Mercator projection for navigation.

- 1570–1572 Atlas of Europe. A unique collection of maps, some assembled from Mercator's earlier works.

- 1578 Ptolemy's Geographia. Mercator's updated and definitive version of Ptolemy's ancient maps.

- 1585 Atlas: France, Low Countries, Germany. The first collection of 51 modern maps by Mercator.

- 1589 Atlas: Italy, Balkans, Greece. A second collection of 23 modern maps.

- 1595 Atlas. Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura. (Atlas or cosmographical meditations upon the creation of the universe, and the universe as created.) Published after his death, this was the first time "Atlas" was used as a title for a map collection. It included all his previous maps and new ones, totaling 102 maps.

Books

- 1540 Literarum latinarum, quas italicas, cursorias que vocant, scribendarum ratio (How to write the Latin letters which they call italic or cursive). A manual on italic script.

- 1569 Chronologia (Chronology). A large book listing important historical events since the beginning of the world.

See also

In Spanish: Gerardus Mercator para niños

In Spanish: Gerardus Mercator para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |