Mercator 1569 world map facts for kids

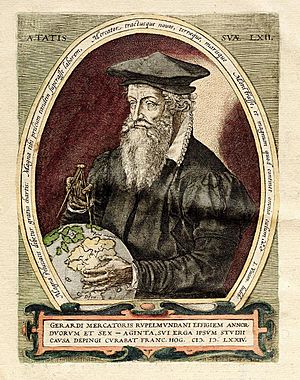

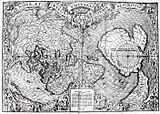

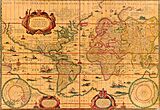

The Mercator world map of 1569 is a famous map created by Gerardus Mercator. Its full Latin title means "New and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation." This long title tells us that Mercator wanted to show all the known geography of the world at that time. He also wanted to make the map much more useful for sailors.

Mercator's special "correction" made this map revolutionary. It allowed sailors to plot a course with a constant compass bearing as a straight line. This is the main feature of the Mercator projection. Even though our knowledge of geography has changed a lot since 1569, Mercator's projection was a huge step forward in map-making. It changed how navigation maps were made and is still used today.

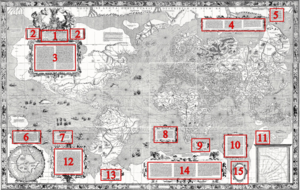

The map itself has a lot of writing on it. These writings, called legends or cartouches, explain many things. They include a dedication to Mercator's supporter and a copyright notice. They also talk about how to use the map for sailing. Some parts even describe imaginary places like the North Pole or a large southern continent. There are also smaller notes about magnetic poles, distances, and even myths about giants and cannibals.

Mercator used ideas from other mapmakers and his own earlier works. But he also said he learned a lot from new charts made by Portuguese and Spanish sailors. Before Mercator, world mapmakers often ignored the practical charts used by sailors. Sailors, in turn, didn't always use the more general world maps. But the Age of Discovery, starting in the late 1400s, brought these two types of map-making together. Mercator's map was one of the first results of this important combination.

Copies of the Map

Mercator's 1569 map was very large. It showed the round Earth flattened onto a flat surface. He printed it on eighteen separate sheets of paper. Each sheet was about 33 by 40 centimeters. When put together, the whole map measured about 202 by 124 centimeters.

We don't know exactly how many copies were printed, but it was likely hundreds. However, by the mid-1800s, only one copy was known to exist. This copy was in the National Library of France.

In 1889, a second copy was found in a library in Breslau. Sadly, both these maps were destroyed by fire in 1945. Luckily, copies had been made before then. A third copy was later found in Switzerland, at the University of Basel. The only other complete copy was found in 1932. It is now in the Maritime Museum Rotterdam.

Many paper copies of these maps have been made. Some are full-size, showing all the amazing details of Mercator's work. You can also find digital images of some of these maps online.

The Basel Map

The Basel map is considered the clearest of the surviving copies. It was printed in three separate rows, not as one big sheet. Full-size reproductions of this map have been made, allowing people to see all its details.

The Paris Map

The Paris copy is a single combined sheet. It is uncolored and in poor condition because it was shown many times. Digital images of this map are available online. These images are high-resolution, meaning you can zoom in and read even the smallest text.

The Breslau Map

After it was found in 1889, many copies of the Breslau map were made. These copies were printed on multiple sheets.

The Rotterdam Map

This copy is part of an atlas that Mercator made for his friend. He created it by cutting and reassembling parts of his original wall map. This allowed him to group areas like continents or oceans together. You can view these pages online, though the resolution is not as high as the Paris copy.

Old World Maps

Here are some world maps made before 1569. They show how map-making changed over time.

- Some world maps of the Renaissance up to 1569 — various projections

-

D. Ribeiro 1529 (Padrón Real)

Here are some regional maps from before 1569.

- Some regional maps before 1569

-

The Zeno map 1558

Key Features of Mercator's Map

Mercator's Projection

Mercator wanted his map to show locations accurately. He also wanted to show true directions and distances. He knew that older maps had problems. On those maps, lines of longitude and latitude often crossed at odd angles. This made shapes look wrong and distances hard to measure. Sailors found it difficult to use these maps for navigation.

Mercator's solution was clever. He made all lines of longitude parallel and straight. He also made them cross latitude lines at perfect right angles. To do this, he had to stretch the map more and more as it got closer to the poles. This stretching meant that areas near the poles look much larger than they are in reality. For example, Greenland looks huge on a Mercator map.

This stretching was important for sailors. It meant that a straight line on the map was a line of constant compass bearing. This is called a rhumb line. Sailors could simply draw a straight line from their starting point to their destination. Then they could follow that compass direction. This made long-distance navigation much easier.

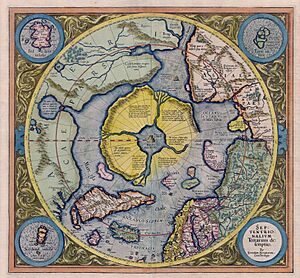

Mercator knew his map couldn't show the very poles. The stretching would become infinite there. So, he used a different type of map for the North Pole area.

It took many years for Mercator's projection to become popular. But by the late 1600s, it was widely used for sea charts.

- The first maps on the Mercator projection

Measuring Distances

Mercator's map also helped sailors measure distances. He explained the difference between a great circle and a rhumb line. A great circle is the shortest distance between two points on a sphere. A rhumb line is a path of constant compass bearing. Rhumb lines are usually longer than great circles, especially over long distances.

Mercator provided a special diagram on his map called the Organum Directorium. This "Diagram of Courses" helped sailors calculate rhumb line distances. They used a compass and a thread to find the distance. This was a big help for navigation at the time.

Prime Meridian and Magnetic Pole

Mercator believed the Prime Meridian (the 0-degree longitude line) should be where a compass needle points exactly north. He thought this was near the Cape Verde islands or the Azores. On his map, the prime meridian is labeled 360 degrees. Other meridians are labeled every ten degrees eastward.

He also tried to figure out the location of the magnetic pole. He used information about how compasses varied in different places. He showed two possible magnetic poles on his map. He did not show a south magnetic pole. At that time, people weren't sure how many magnetic poles the Earth had. Later, Mercator realized that magnetic direction changes over time. This meant his idea for the prime meridian wasn't perfect.

Geography on the Map

Mercator used many sources for his map. He looked at other world maps and regional maps. He also used new charts from Portuguese and Spanish sailors. He tried to combine all this information to make the most accurate map possible.

However, there are still big differences between Mercator's map and modern maps. Europe, the coast of Africa, and the eastern coast of the Americas are shown fairly well. But the further away from Europe, the more errors appear. For example, the western coast of South America is shown with a strange bulge. This mistake was later corrected on maps by other cartographers.

The Mediterranean Sea also has some errors. The Black Sea is shown too far north. The entire Mediterranean basin is stretched out too much from east to west.

Mercator's map also includes some mythical islands. These include Frisland and Brasil in the North Atlantic. He also showed a Strait of Anian between Asia and the Americas. This was a supposed shortcut to the spice islands. He based this on old writings, as these areas were not yet explored.

The North Pole region on the map looks very strange. It shows four channels where the sea rushes towards the pole. There, it supposedly disappears into a giant abyss. Mercator got this idea from a 14th-century English friar.

Mercator also believed in a large Southern continent, called Terra Australis. People thought this continent had to exist to balance the land in the Northern Hemisphere. This belief lasted until explorers sailed around Cape Horn and Australia.

The interiors of continents were mostly unknown back then. Mercator tried to fill them in with information from old texts. He wrote about the Asian Prester John and the courses of rivers like the Ganges, Nile, and Niger. He often quoted ancient writers like Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy. He also likely talked to travelers of his time.

Mercator himself was not a sailor. While his projection was a great idea, his map had some practical problems for navigation. It was hard to use because there wasn't good information about magnetic declination. Also, it was difficult to figure out longitude accurately at sea.

Because of these issues, Mercator's projection wasn't widely used for sea charts until the 1700s.

Decorative Features

- High resolution details

The map has a beautiful, detailed border. It shows the 32 points of the compass. The main directions (north, east, south, west) are written in several languages. This shows Mercator wanted sailors to use his map.

Mercator also decorated the open seas with ships and sea creatures. One striking figure might be Triton, a sea god. The unknown parts of the continents are mostly empty. Mercator added mountains, rivers, and cities based on what he thought might be there.

In South America, he drew an animal with a pouch for its young. He also showed cannibals. The giants in Patagonia might be based on real encounters. Spanish sailors, who were shorter, were surprised by tall native tribes. These images of South Americans are similar to those on maps by Diego Gutierrez.

Other figures on the map include:

- Prester John in Ethiopia.

- Two small "flute" players.

- The Zolotaia baba, a mythical idol.

Mercator also created the italic writing style used on the map. He believed it was much clearer than other styles. He even published a book showing how to write in italic script.

Map Texts

The map contains many detailed texts, called legends and minor texts. These provide explanations and information about the map's features and the geography of the world as understood by Mercator.

|

Links to the |

Summary of the Legends

- Legend 1: A dedication to Mercator's supporter, the Duke of Cleves.

- Legend 2: A poem praising the good rule of the Duke of Cleves.

- Legend 3: Mercator explains his goals for the map. He wanted to show accurate locations and distances for sailors. He also aimed to show countries' true shapes and respect ancient geographical knowledge.

- Legend 4: Discusses the Asian Prester John and the origins of the Tartars.

- Legend 5: Explains Mercator's idea for choosing the prime meridian based on where a compass points true north.

- Legend 6: Describes the North Pole regions, including the idea of four channels leading to an abyss.

- Legend 7: Mentions Ferdinand Magellan's journey around the world.

- Legend 8: Discusses the Niger and Nile rivers and their possible connection.

- Legend 9: Notes Vasco da Gama's voyage around Africa to India.

- Legend 10: Explains how to use the Organum Directorium (Diagram of Courses) to measure rhumb line distances.

- Legend 11: Discusses the Southern Continent (Terra Australis) and its relation to Java.

- Legend 12: Explains the difference between great circles and rhumb lines and how to measure rhumb lines.

- Legend 13: Refers to the 1493 papal decision that divided new lands between Spain and Portugal.

- Legend 14: Discusses the Ganges and the geography of Southeast Asia.

- Legend 15: A copyright notice protecting Mercator's work from being copied.

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |