Patagonia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Patagonia

|

|

|---|---|

|

Region of South America

|

|

|

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,043,076 km2 (402,734 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,999,540 |

| • Density | 1.916965/km2 (4.964916/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Patagonian |

| Demographics | |

| • Languages | Chilean Spanish, Rioplatense Spanish, English, Mapudungun, Welsh |

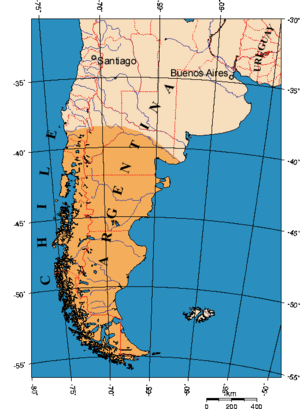

Patagonia is a huge area at the southern tip of South America. It is shared by two countries: Argentina and Chile. This region is known for its amazing natural beauty. You can find the southern Andes Mountains, clear lakes, deep fjords, and massive glaciers in the west. To the east, there are dry deserts, flat tablelands, and grassy steppes.

Patagonia is surrounded by water. The Pacific Ocean is to its west, and the Atlantic Ocean is to its east. Important waterways like the Strait of Magellan, the Beagle Channel, and the Drake Passage connect these oceans to the south.

The Colorado and Barrancas rivers usually mark the northern border of Argentine Patagonia. Sometimes, the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego is also included as part of Patagonia. In Chile, the northern border is often considered to be at the Huincul Fault in the Araucanía Region.

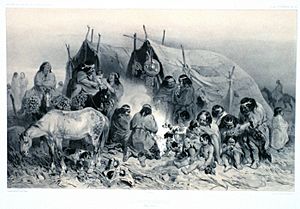

When the Spanish first arrived, many different native tribes lived in Patagonia. Some groups in the northwest grew crops. Most people, however, were hunter-gatherers. They traveled on foot in eastern Patagonia or used dugout canoes and dalcas in the western fjords. Later, native groups in northeastern Patagonia learned to ride horses.

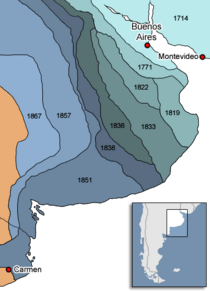

At first, Spain mainly wanted to keep other European countries away from Patagonia. But later, independent Chile and Argentina slowly started to settle the area in the 1800s and early 1900s. This led to a big decrease in the native populations. Their way of life and homes were changed. At the same time, thousands of people from Europe, Argentina, and Chile moved to Patagonia. There were often border disputes between Argentina and Chile in the 1900s. Today, most of these disagreements have been solved, except for a small part along the Southern Patagonian Ice Field.

Today, the economy in eastern Patagonia focuses on sheep farming and getting oil and gas from the ground. In western Patagonia, fishing, salmon farming, and tourism are very important. Patagonia has a rich mix of cultures, including Criollo, Mestizo, Indigenous, and European influences.

Contents

Understanding the Name Patagonia

The name Patagonia comes from the word patagón. In 1520, Ferdinand Magellan used this word to describe the native tribes he met. His expedition thought these people were giants. Today, we believe these "Patagons" were the Tehuelche, who were generally taller than Europeans at that time.

One idea from Argentine researcher Miguel Doura suggests the name Patagonia might come from an ancient Greek region called Paphlagonia. This place was possibly home to a character named "Patagon" in old adventure stories printed in 1512. This was 10 years before Magellan reached these southern lands.

There are also many place names in the Chiloé Archipelago that come from the Chono language. Even though the main native language there when the Spanish arrived was Mapudungun. Some theories explain this by saying the Cuncos moved to Chiloé Island long ago. They were pushed south by other tribes. Even some volcanoes in western Patagonia, outside traditional Huilliche land, have names from the Huilliche language.

In Chubut Province, modern place names come from native peoples, Welsh settlers, and names linked to the "project of the Argentine state."

People and Land Area

Patagonia covers a huge area. About 10% is in Chile, and 90% is in Argentina.

Major Cities in Patagonia

Here are some of the biggest cities in Patagonia:

| City | Population | Province / Region | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuquén | 377,500 (Metropolitan area) | Neuquén Province | Argentina |

| Temuco | 277,529 (Metropolitan area) | Araucanía Region | Chile |

| Comodoro Rivadavia | 182,631 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

| Puerto Montt | 169,736 (Metropolitan area) | Los Lagos Region | Chile |

| Valdivia | 150,048 | Los Ríos Region | Chile |

| Osorno | 147,666 | Los Lagos Region | Chile |

| Punta Arenas | 123,403 | Magallanes Region | Chile |

| General Roca | 120,883 | Río Negro Province | Argentina |

| Puerto Madryn | 115,353 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

| San Carlos de Bariloche | 112,887 | Río Negro Province | Argentina |

| Santa Rosa | 103,241 | La Pampa Province | Argentina |

| Trelew | 97,915 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

| Río Gallegos | 95,796 | Santa Cruz Province | Argentina |

| Viedma | 80,632 | Río Negro Province | Argentina |

| Ushuaia | 77,819 | Tierra del Fuego Province | Argentina |

| Río Grande | 67,038 | Tierra del Fuego Province | Argentina |

| Coyhaique | 49,667 | Aysén Region | Chile |

| Esquel | 34,900 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

Patagonia's Amazing Landscapes

Most of Argentine Patagonia is made up of flat, steppe-like plains. These plains rise in steps, like huge terraces, each about 100 meters (330 feet) higher than the last. They are covered with a lot of shingle (small stones) and have very little plant life. In the low areas of the plains, you can find ponds or lakes with fresh or salty water.

As you move towards Chile, the shingle changes to porphyry, granite, and basalt rocks from volcanoes. Here, you'll see more animals and plants. The plants are much greener, mainly southern beech trees and conifers. The western Andes mountains get a lot of rain. The cold ocean temperatures also create cold, wet air. This leads to the huge ice fields and glaciers, which are the largest outside of Antarctica in the Southern Hemisphere.

Many valleys cut across the plateau. Some of the main ones are the Gualichu, Maquinchao, Valcheta, Senguerr, and Deseado River. Some of these valleys used to be ancient paths between the oceans. Other valleys hold large lakes, like Musters and Colhue Huapi.

Across much of Patagonia east of the Andes, volcanic eruptions have created flat areas of basalt lava over millions of years. Older lava plains are found at higher elevations than newer ones.

Over time, melting ice and changes in the Earth's crust have carved out deep valleys. These valleys often separate the flat plateau from the first tall hills, which are called the pre-Cordillera. West of these hills, another long valley runs along the base of the snowy Andes mountains. This last valley has the richest and most fertile land in Patagonia. Lakes along the Andes, like Lake Argentino and Lake Fagnano, were also formed by ice streams. Even coastal bays like Bahía Inútil were shaped this way.

How Patagonia's Land Was Formed

Geologists believe the Huincul Fault is the geological boundary of Patagonia. This fault line marks a big change in the types of rocks found. The ages of the bedrock change suddenly across this fault.

Scientists have different ideas about how Patagonia's landmass was formed. Some, like Víctor Alberto Ramos, think Patagonia was once a separate piece of land (a "terrane") that broke away from Antarctica. They believe it then joined South America about 250 to 270 million years ago. However, a 2014 study by Robert John Pankhurst and his team suggests that Patagonia likely formed closer to South America.

Ancient deposits from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras have shown amazing vertebrate fossils. For example, the skull of an ancient turtle called Niolamia was found. It looks almost exactly like a turtle found in Australia, showing a past connection between these continents. Fossils of Argentinosaurus, possibly the largest dinosaur ever, have been found in Patagonia. A model of the Piatnitzkysaurus dinosaur is even at the Trelew airport!

The Los Molles Formation and Vaca Muerta formation in the Neuquén basin are also very important. They contain huge amounts of oil and gas. Other interesting fossils from Patagonia include giant flightless birds and a very large mammal called Pyrotherium. Many fossils of cetaceans (like whales and dolphins) have also been found in ancient marine rocks.

During the Oligocene and early Miocene periods, large parts of Patagonia were covered by the sea. This might have temporarily connected the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. This connection would have been through narrow, shallow seas that formed channels. About 14 million years ago, the Antarctic Plate began to slide under South America. This caused the land to lift up by about 1 kilometer (0.6 miles), which made the sea retreat from Patagonia.

How Patagonia is Divided

Patagonia is split between two countries: Chile (10%) and Argentina (90%). Both countries have different ways of dividing their parts of Patagonia. Argentina has provinces and departments. Chile has regions, provinces, and communes. Argentine provinces have their own elected leaders and lawmakers. Chilean regions have leaders appointed by the government.

The Argentine provinces in Patagonia are La Pampa, Neuquén, Río Negro, Chubut, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego. The very southern part of Buenos Aires Province can also be seen as part of Patagonia.

In Chile, the two regions fully in Patagonia are Aysén and Magallanes. Palena Province, which is part of the Los Lagos Region, is also in Patagonia. Some definitions also include the Chiloé Archipelago, the rest of the Los Lagos Region, and part of the Los Ríos Region as part of Patagonia.

Patagonia's Climate and Weather

Overall, Patagonia has a cool and dry climate. The east coast is warmer than the west, especially in summer. This is because a warm ocean current reaches the east coast, while the west coast has a cold current. However, winters are colder on the inland plains east of the mountains and further south on the southeast coast.

For example, in Puerto Montt, Chile, the average yearly temperature is 11°C (52°F). In Bahía Blanca, Argentina, just north of Patagonia, the average is 15°C (59°F), but temperatures can swing much more widely. In Punta Arenas, in the far south, the average is 6°C (43°F).

The winds mostly blow from the west. This means the western side of the Andes gets a lot more rain than the eastern side. This is called a rainshadow effect. The western islands near Torres del Paine can get 4,000 to 7,000 mm (157 to 276 inches) of rain each year. But the eastern hills get less than 800 mm (31 inches), and the plains can get as little as 200 mm (8 inches).

Rainfall changes a lot with the seasons in northwestern Patagonia. For example, Villa La Angostura in Argentina gets a lot of rain and snow in May, June, and July. But in February and March, it gets much less. The total for the city is 2074 mm (82 inches), making it one of the rainiest places in Argentina. Further west, some areas get over 4,000 mm (157 inches), especially on the Chilean side. In the northeast, most rain falls from summer thunderstorms, but totals are low, barely reaching 500 mm (20 inches).

The Patagonian west coast, which is only in Chile, has a cool ocean climate. Summer temperatures range from 14°C (57°F) in the south to 19°C (66°F) in the north. It rains a lot, from 2,000 to over 7,000 mm (79 to 276 inches) in some small areas. Snow is rare on the northern coast but more common in the south. Frost is usually not very strong.

Right east of the coast are the Andes mountains. They have deep fjords in the south and deep lakes in the north. Temperatures change with how high up you are. The tree line (where trees stop growing) is around 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) in the north. It drops to only 600–800 meters (1,970–2,620 feet) in Tierra del Fuego. Rainfall also changes quickly as you go east. For example, Laguna Frías in Argentina gets 4,400 mm (173 inches) of rain yearly. Bariloche, about 40 km (25 miles) east, gets about 1,000 mm (39 inches). Its airport, another 15 km (9 miles) east, gets less than 600 mm (24 inches).

The eastern slopes of the Andes are home to several Argentine cities. These include San Martín de los Andes, Bariloche, El Bolsón, Esquel, and El Calafate. Summers here are milder, and winters are much colder with frequent snow.

East of these areas, the weather gets much tougher. Rain drops to between 150 and 300 mm (6 to 12 inches). The mountains no longer block the wind, and temperatures become more extreme. Maquinchao, a few hundred kilometers east of Bariloche, has summer days that are usually about 5°C (9°F) warmer. But winter temperatures are much more extreme, with records as low as −35°C (−31°F). The plains in Santa Cruz province and parts of Chubut often have snow cover all winter. In Chile, the city of Balmaceda is known for being the coldest place in the country, with temperatures sometimes falling below −20°C (−4°F).

The northern Atlantic coast has warm summers and mild winters. Rainfall is very low. Further south in Chubut, the weather gets a bit colder. Comodoro Rivadavia has summer temperatures of 24 to 28°C (75 to 82°F) and winters around 10°C (50°F). But as you move south to Santa Cruz, there's a big drop in temperature. Río Gallegos, in the south of the province, has cooler summers and colder winters. Snowfall is common despite the dryness. Rio Gallegos is also one of the windiest places on Earth.

Tierra del Fuego is very wet in the west, quite damp in the south, and dry in the north and east. Summers are cool and often cloudy in the south, and very windy. Winters are dark and cold. In the east and north, winters are much harsher, with cold snaps bringing temperatures down to −20°C (−4°F) in places like Rio Grande. Snow can even fall in the summer in most areas.

Animals of Patagonia

The most common mammals on the Patagonian plains are the guanaco (a type of llama), the cougar, the Patagonian fox, the Patagonian hog-nosed skunk, and the Magellanic tuco-tuco (a rodent that lives underground).

The Patagonian steppe is one of the last places where you can find many guanacos and Darwin's rheas (large birds similar to ostriches). Native people used to hunt them for their skins using boleadoras (throwing weapons). Before guns and horses, these animals were the main food source for the natives. Vizcachas (rodents) and the Patagonian mara (a large rodent) are also common in the steppe and northern grasslands.

Bird life is rich here. The crested caracara (a type of falcon) is a common sight. You can see austral parakeets as far south as the Strait of Magellan. Even green-backed firecrowns, a type of hummingbird, can be seen flying in the snow. One of the world's largest birds, the Andean condor, also lives in Patagonia. Many waterfowl, like the Chilean flamingo, the upland goose, and unique steamer ducks, are found here.

Important marine animals include the southern right whale, the Magellanic penguin, the killer whale, and elephant seals. The Valdés Peninsula is a World Heritage Site. It is important for protecting marine mammals.

Patagonia's freshwater fish are not as many as in other similar places. The Argentine part has 29 freshwater fish species, with 18 being native. Some fish, like several types of trout and common carp, were brought here from other places. Native fish include Aplochiton and Galaxias, temperate perches, catfish, and Neotropical silversides. Patagonia also has a very unusual crustacean called the aeglid.

Patagonia's History

Early Human Life (10,000 BC – AD 1520)

People have lived in Patagonia for thousands of years. Some of the oldest findings date back to at least 13,000 BC. More certain evidence shows human activity around 10,000 BC. For example, at Monte Verde in Chile, there's evidence from about 12,500 BC. It would have been hard to live there during the ice age because of the ice and melting water.

The region seems to have been lived in continuously since 10,000 BC. Different cultures and groups of people moved through the area. Many ancient sites have been found. These include caves like Cueva del Milodon in southern Patagonia and Tres Arroyos on Tierra del Fuego. These sites support the early dates of human life. Evidence of campfires, stone tools, and animal remains from 9400–9200 BC have been found east of the Andes.

The Cueva de las Manos (Cave of the Hands) in Santa Cruz, Argentina, is a famous site. This cave has amazing wall paintings, especially many handprints. These paintings are thought to be from around 8000 BC.

Based on old tools, hunting guanaco and rhea (a large bird) were the main food sources for tribes on the eastern plains. It's not clear if large animals like ground sloths and horses were already gone before humans arrived. It's also not clear if early humans had domestic dogs. Bolas (throwing weapons) are often found and were used to catch guanaco and rhea. People also lived along the Pacific coast, using boats. The last groups to do this were the Yaghan and Kaweshqar people.

The native peoples of the region included the Tehuelches. Their numbers and way of life changed a lot after Europeans arrived. The Tehuelches included different groups like the Gununa'kena in the north and the Aonikenk in the far south. On Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, the Selk'nam and Haush lived. In the southern islands, the Yámana and Kawéskar lived. The Chono people lived in the northern Patagonian islands. These groups had different ways of life, body decorations, and languages when Europeans first met them.

Towards the end of the 1500s, Mapuche-speaking farmers moved into the western Andes. From there, they spread across the eastern plains and south. They became very powerful and came to rule over other peoples in the region. Today, the Mapuche are the main native community.

First European Explorers (1520–1669)

Some explorers, like Amerigo Vespucci, might have reached Patagonia as early as 1502. However, his descriptions were not very accurate.

The first detailed description of Patagonia's coast might come from a Portuguese voyage in 1511–1512. This expedition reached the San Matias Gulf, at 42°S. They explored the gulf and saw the continent on the southern side.

The Atlantic coast of Patagonia was fully explored in 1520 by a Spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan. As he sailed along the coast, he named many places, like San Matías Gulf and Cape Virgenes. Magellan's ships spent a difficult winter at Puerto San Julián. During this time, they met the local people, likely Tehuelche people. Magellan's reporter, Antonio Pigafetta, described them as giants called Patagons.

In 1529, the Spanish Crown gave the territory to Governor Simón de Alcazaba y Sotomayor. This area was called the Governorate of New Léon. It was later redefined in 1534 to include the southernmost part of South America and the islands towards Antarctica.

Rodrigo de Isla, sent inland in 1535, was likely the first European to cross the great Patagonian plain. He might have even crossed the Andes to the Pacific coast if his men had not rebelled.

Pedro de Mendoza founded Buenos Aires but did not go south. Other explorers like Alonso de Camargo (1539), Juan Ladrilleros (1557), and Hurtado de Mendoza (1558) helped map the Pacific coasts. Francis Drake's voyage in 1577 was famous. But the best descriptions of Patagonia's geography came from Spanish explorer Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (1579–1580). He carefully mapped the southwest region. The settlements he founded were later abandoned. One was so desolate that Thomas Cavendish called it Port Famine in 1587.

After the route around Cape Horn was discovered, Spain lost interest in southern Patagonia until the 1700s. Then, they set up coastal settlements like Carmen de Patagones.

In 1669, John Davis explored the area around Puerto Deseado. In 1670, Sir John Narborough claimed it for King Charles II of England. But the English did not try to settle there.

Stories of Patagonian Giants

The first European explorers in Patagonia noticed that the native people were taller than average Europeans. This made some believe that Patagonians were giants.

Antonio Pigafetta, who wrote about Magellan's journey, said Magellan called the people Patagão or Patagón. He also named the region "Patagonia." While Pigafetta didn't explain the name, many thought it meant "land of the big feet." However, it's more likely that the name came from a character named "Patagón" in a popular Spanish adventure novel from 1512. Magellan probably thought the native people, dressed in animal skins and eating raw meat, were like the wild Patagón in the book.

Pigafetta's reports of meeting people 9 to 12 feet tall made Europeans believe in Patagonian giants. Other explorers, like Sir Francis Drake, seemed to confirm these stories. Early maps of the New World sometimes even wrote "region of the giants" in the Patagonian area.

The belief in giants continued for 250 years. It was revived in 1767 when an anonymous report was published about Commodore John Byron's voyage. This report claimed to prove the giants existed. It became a huge bestseller.

However, the excitement about Patagonian giants died down a few years later. In 1773, John Hawkesworth published official journals from explorers like James Cook and John Byron. These journals showed that the people Byron met were no taller than 6 feet 6 inches (2 meters). They were very tall but not giants. Interest in the giants faded, but some people still believed in them even into the 1900s.

Spanish Outposts and Scientific Exploration (1764–1842)

Spain failed to settle the Strait of Magellan. So, the Chiloé Archipelago became important for protecting western Patagonia from other countries. Valdivia and Chiloé were key places where Spain gathered information about Patagonia.

To stop enemies from getting help from native people, Spanish leaders ordered the Guaitecas Archipelago to be emptied. Most of the native Chono moved to the Chiloé Archipelago. Some moved south, leaving the area empty in the 1700s.

In the late 1700s, European knowledge of Patagonia grew. Explorers like John Byron (1764–1765), Samuel Wallis (1766), and Louis Antoine de Bougainville (1766) made voyages. Thomas Falkner, a Jesuit who lived there for nearly 40 years, published his Description of Patagonia (1774). Francisco Viedma founded El Carmen (now Carmen de Patagones). Antonio settled the San Julian Bay area and founded Floridablanca (1782). Basilio Villarino traveled up the Rio Negro (1782).

Two important hydrographic surveys of the coasts were done. The first (1826–1830) included HMS Adventure and HMS Beagle. The second (1832–1836) was the voyage of the Beagle with Charles Darwin. Darwin spent a lot of time exploring Patagonia on land. He rode with gauchos in Río Negro and joined an expedition up the Santa Cruz River.

Independence and Colonization (1843–1902)

During the independence wars, there were rumors that Spanish troops would come to Patagonia. In 1820, Chilean leader José Miguel Carrera teamed up with the native Ranquel people to fight rivals in Buenos Aires.

The last royalist group in Argentina and Chile, the Pincheira brothers, moved into northern Patagonia. This group was made of Spanish, Mestizos, and native people. They allied with the Ranqueles and Boroanos tribes. In Patagonia, far from the control of Chile and Argentina, the Pincheira brothers set up camps. From there, they raided the new republics.

In the early 1800s, the araucanization of native people in northern Patagonia grew. Many Mapuches moved to Patagonia to live as nomads, raising cattle or raiding the Argentine countryside. The stolen cattle were taken to Chile through mountain passes and traded for goods, especially alcohol. The main trade route was called Camino de los chilenos. To stop the raids, Argentina built a trench called the Zanja de Alsina in the 1870s.

In the mid-1800s, Argentina and Chile began to expand aggressively into the south. This led to more conflicts with the native peoples. In 1860, a French adventurer, Orelie-Antoine de Tounens, declared himself king of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia of the Mapuche.

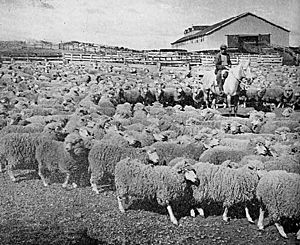

Following instructions from Bernardo O'Higgins, Chilean president Manuel Bulnes sent an expedition to the Strait of Magellan. They founded Fuerte Bulnes in 1843. Five years later, the Chilean government moved the main settlement to Punta Arenas, the oldest permanent settlement in Southern Patagonia. This helped Chile claim the Strait of Magellan. In the 1860s, sheep from the Falkland Islands were brought to the area. Sheep farming grew to be the most important part of the economy in southern Patagonia.

George Chaworth Musters traveled with a group of Tehuelches in 1869. He went from the strait to the northwest, learning a lot about the people and their way of life.

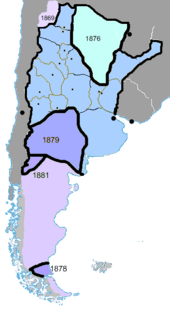

The Conquest of the Desert and the 1881 Treaty

Argentine leaders worried that the strong ties between the araucanized tribes and Chile would give Chile influence over the plains. They feared that in a war with Chile over Patagonia, the natives would side with the Chileans. This could bring the war close to Buenos Aires.

The decision to carry out the Conquest of the Desert was likely sped up by an attack in 1872. Cufulcurá and his 6,000 followers attacked cities in Argentina. They killed 300 people and took 200,000 cattle. In the 1870s, the Conquest of the Desert was a controversial campaign by the Argentine government. It was led mainly by General Julio Argentino Roca. The goal was to control or, some say, remove the native peoples of the south.

In 1885, a mining group led by Julius Popper landed in southern Patagonia. They found gold near Tierra del Fuego. This opened up the area to more prospectors. European missionaries and settlers arrived throughout the 1800s and 1900s. This included the Welsh settlement in the Chubut Valley. Many Croatians also settled in Patagonia.

In the early 1900s, the border between Argentina and Chile in Patagonia was set with help from the British crown. Many changes have been made since then. The last conflict was solved in 1994. It gave Argentina control over the Southern Patagonia Icefield, Cerro Fitz Roy, and Laguna del Desierto.

Until 1902, many people in Patagonia were natives of the Chiloé Archipelago (Chilotes). They worked as laborers on large sheep farms. Their social status was below that of the gauchos and the landowners.

Around 1902, when the borders were drawn, Argentina expelled many Chilotes. They feared that having a large Chilean population in Argentina could threaten their future control. These workers founded the first Chilean settlement inland in what is now the Aysén Region, called Balmaceda. Since there wasn't good grassland on the forest-covered Chilean side, the immigrants burned down the forest. These fires could last for more than two years.

Patagonia's Economy

The main economic activities in Patagonia have been mining, whaling, and raising livestock (especially sheep). There is also farming (wheat and fruit) near the Andes in the north. After oil was found near Comodoro Rivadavia in 1907, oil production became very important.

Energy production is also a key part of the local economy. Railways were planned to cover Argentine Patagonia to help the oil, mining, farming, and energy industries. A line was built connecting San Carlos de Bariloche to Buenos Aires. Parts of other lines were built to the south. Today, only a few lines are still used. These include La Trochita in Esquel and the Train of the End of the World in Ushuaia, which are both heritage lines.

In the western, forest-covered Patagonian Andes and islands, wood logging has always been important. It helped people settle areas like the Nahuel Huapi and Lácar lakes in Argentina and the Guaitecas Archipelago in Chile.

Sheep Farming

Sheep farming started in the late 1800s and became a main economic activity. It was at its peak during the First World War. But then, world wool prices dropped, which hurt sheep farming in Argentina. Today, about half of Argentina's 15 million sheep are in Patagonia. This percentage is growing as sheep farming disappears in the northern grasslands. Chubut (mainly Merino sheep) is the top wool producer, with Santa Cruz (Corriedale and some Merino) second.

Sheep farming improved in 2002 when the Argentine peso lost value and there was more demand for wool globally. However, there isn't much investment in new slaughterhouses. Also, rules about plant and animal health often limit the export of sheep meat. Large valleys in the Andes provide good grazing land. The dry, cool weather in the south is good for raising Merino and Corriedale sheep.

Other livestock include small numbers of cattle, pigs, and horses. Sheep farming provides a small but important number of jobs in rural areas where there are not many other jobs.

Tourism in Patagonia

In the second half of the 1900s, tourism became more and more important to Patagonia's economy. At first, it was a remote place for backpackers. Now, more wealthy visitors, cruise passengers going around Cape Horn or to Antarctica, and adventure travelers come here.

Main tourist spots include the Perito Moreno glacier, the Valdés Peninsula, the Argentine Lake District, and Ushuaia and Tierra del Fuego. Ushuaia is also a starting point for trips to Antarctica, bringing even more visitors. Tourism has created new markets for traditional crafts like Mapuche handicrafts, guanaco textiles, and sweets.

Because of more tourism, foreigners have bought large areas of land. These purchases are often for prestige rather than for farming. Buyers have included famous people like Sylvester Stallone, Ted Turner, and Christopher Lambert. The largest landowner is Luciano Benetton. His company has brought new methods to the sheep-rearing industry. It has also supported museums and community facilities. However, it has faced criticism, especially for how it treats local Mapuche communities.

Energy Production

Because there is little rainfall in farming areas, Argentine Patagonia has many dams for irrigation. Some of these dams also produce hydropower (electricity from water). The Limay River has five dams that generate hydroelectricity. These dams, along with the Cerros Colorados Complex on the Neuquén River, produce more than a quarter of Argentina's total hydroelectric power.

Coal is mined in the Rio Turbio area and used to make electricity. Patagonia's strong winds have made the area Argentina's main source of wind power. There are plans to greatly increase wind power generation.

Patagonian Food

Argentine Patagonian food is similar to the food in Buenos Aires, with grilled meats and pasta. However, it uses more local ingredients and fewer imported products. Lamb is seen as the traditional Patagonian meat. It is grilled for several hours over an open fire. Some guidebooks say that game meat, especially guanaco and introduced deer and boar, are popular in restaurants. However, since the guanaco is a protected animal, it is not commonly found in restaurants.

Trout and centolla (king crab) are also common. But too much fishing of centolla has made it harder to find. In the area around Bariloche, there is a strong Alpine cuisine tradition. You can find chocolate shops and even fondue restaurants. Tea rooms are popular in the Welsh communities of Gaiman and Trevelin, and in the mountains. Since the mid-1990s, winemaking has had some success in Argentine Patagonia, especially in Neuquén.

Images for kids

-

Ainsworth Bay and Marinelli Glacier, Chile.

See also

In Spanish: Patagonia para niños

In Spanish: Patagonia para niños