Mapuche facts for kids

Lautaro, a hero of the Arauco War; Rayén Quitral, a famous singer; a modern Mapuche woman; Ceferino Namuncura, a blessed person in the Catholic Church.

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1,950,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Chile | 1,745,147 (2017) |

| Argentina | 205,009 (2010) |

| Languages | |

|

|

| Religion | |

| Catholicism, Evangelicalism, traditional Mapuche beliefs | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

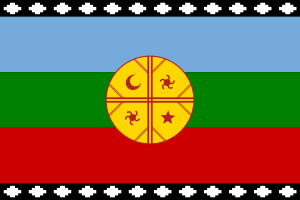

The Mapuche are a group of indigenous people living in south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina. This includes parts of a region called Patagonia. The word "Mapuche" refers to many different groups who share a similar way of life, religion, economy, and language, which is called Mapudungun.

Their influence once reached from the Aconcagua Valley to the Chiloé Archipelago. Later, they moved east into a land called Puelmapu, which is part of the Argentine pampa and Patagonia. Today, Mapuche people make up over 80% of the indigenous population in Chile. They are especially common in the Araucanía region. Many Mapuche have moved from the countryside to cities like Santiago and Buenos Aires to find work.

The Mapuche traditionally farmed the land. Their social groups were based on large families, led by a lonko or chief. During wars, different Mapuche groups would join together. They would choose a toki (meaning "axe-bearer") to lead them. Mapuche culture is famous for its beautiful textiles (woven fabrics) and silver jewelry.

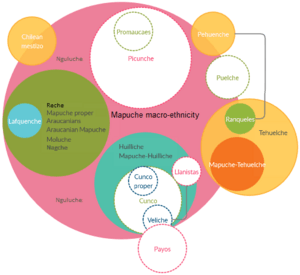

When the Spanish arrived, the Mapuche lived in valleys between the Itata and Toltén rivers. Further south, the Huilliche and Cunco lived down to the Chiloé Archipelago. In the 1600s, 1700s, and 1800s, some Mapuche groups moved east into the Andes mountains and the pampas. They mixed with or formed ties with other groups like the Poya and Pehuenche. Around the same time, groups from the pampa regions, like the Puelche, Ranquel, and northern Aonikenk, met the Mapuche. The Tehuelche adopted the Mapuche language and some of their culture. This process is known as Araucanization. During this time, Patagonia largely came under Mapuche control.

Mapuche people in Spanish-controlled areas, especially the Picunche, mixed with the Spanish during the colonial period. They formed a mixed-heritage population that lost its original indigenous identity. However, Mapuche society in Araucanía and Patagonia stayed independent until the late 1800s. At that time, Chile took control of Araucanía, and Argentina conquered Puelmapu. Since then, the Mapuche have become citizens of these countries. Today, many Mapuche communities are involved in the Mapuche conflict. This conflict is about land and indigenous rights in both Argentina and Chile.

Contents

What Does "Mapuche" Mean?

Historically, Spanish explorers in South America called the Mapuche people Araucanians. Some people now find this term offensive. However, others believe it is important because of the famous book La Araucana. This book, written by Alonso de Ercilla, tells the epic story of the Mapuche's long war against the Spanish Empire. The name "Araucano" likely came from the place name rag ko, which means "clayey water."

Scholars believe that in the early Spanish colonial period, different Mapuche groups (like the Moluche, Huilliche, and Picunche) called themselves Reche. This means "pure people" or "people of pure blood."

The name "Mapuche" is used in two ways. Sometimes it refers to all the Picunche, Huilliche, and Moluche or Nguluche from Araucanía. Other times, it refers only to the Moluche or Nguluche from Araucanía. "Mapuche" is a newer name that means "People of the Earth" or "Children of the Earth." "Mapu" means earth, and "che" means person. This name became popular after the Arauco War.

Mapuche people also identify themselves by the geography of their lands:

- Pwelche or Puelche: These are the "people of the east." They lived in Pwel mapu or Puel mapu, the eastern lands (Pampa and Patagonia in Argentina).

- Pikunche or Picunche: These are the "people of the north." They lived in Pikun-mapu, the "northern lands."

- Williche or Huilliche: These are the "people of the south." They lived in Willi mapu, the "southern lands."

- Pewenche or Pehuenche: These are the "people of the pewen/pehuen." They lived in Pewen mapu, "the land of the pewen (Araucaria araucana) tree."

- Lafkenche: These are the "people of the sea." They lived in Lafken mapu, "the land of the sea." They are also known as Coastal Mapuche.

- Nagche: These are the "people of the plains." They lived in Nag mapu, "the land of the plains." This area is near the Cordillera de Nahuelbuta mountains and the lowlands next to them. Their old name was Reche. Famous Mapuche leaders like Lef-Traru (known as Lautaro), Kallfülikan (known as Caupolicán), and Pelontraru (known as Pelantaro) were Nagche.

- Wenteche: These are the "people of the valleys." They lived in Wente mapu, "the land of the valleys."

Mapuche History

Ancient Times

Archaeological discoveries show that Mapuche culture existed in Chile and Argentina as far back as 600 to 500 BC. Their genes are different from other indigenous people in Patagonia. This suggests they might have come from a different place or were separated for a long time.

Stories say that troops from the Inca Empire reached the Maule River. They had a battle with the Mapuche between the Maule and Itata rivers. Most experts believe the Inca Empire's southern border was between Santiago and the Maipo River, or somewhere between Santiago and the Maule River. This means most Mapuche people were not ruled by the Incas.

When the Mapuche met the Incas, they learned about state organization for the first time. This contact helped them realize they were different from the invaders. It also helped unite them into loose groups, even though they didn't have a formal state.

When the first Spanish arrived in Chile, most indigenous people lived in the Mapuche heartland. This area stretched from the Itata River to Chiloé Island. Historian José Bengoa estimates that between 705,000 and 900,000 Mapuche lived there in the mid-1500s.

The Arauco War

The Spanish arrived in Mapuche territory after conquering Peru. In 1541, Pedro de Valdivia came to Chile from Cuzco and founded Santiago. The northern Mapuche tribes, like the Promaucaes and Picunches, fought the Spanish but were not successful.

In 1550, Pedro de Valdivia wanted to control all of Chile down to the Strait of Magellan. He began a campaign in south-central Chile to conquer more Mapuche land. Between 1550 and 1553, the Spanish built several cities in Mapuche lands. These included Concepción, Valdivia, Imperial, Villarrica, and Angol. They also built forts like Arauco, Purén, and Tucapel.

The Spanish efforts to take more land led to the Arauco War against the Mapuche. This was a long, on-and-off conflict that lasted almost 350 years. The Mapuche did not like being forced to work, which was common under Inca rule. They largely refused to serve the Spanish.

From 1550 to 1598, the Mapuche often attacked Spanish settlements in Araucanía. The war was mostly a series of smaller fights. The number of Mapuche people dropped a lot after they met the Spanish. Wars and diseases greatly reduced their population. Some also died working in Spanish gold mines.

In 1598, a group of warriors from Purén, led by Pelantaro, ambushed Martín García Óñez de Loyola and his soldiers. Almost all the Spanish died. After this, the Mapuche started a big uprising. They destroyed all the Spanish cities in their homeland south of the Biobío River.

In the years after the Battle of Curalaba, a general uprising happened among the Mapuches and Huilliches. Spanish cities like Angol, Imperial, Osorno, Santa Cruz de Oñez, Valdivia, and Villarrica were destroyed or left empty. Only Chillán and Concepción survived Mapuche attacks. Except for the Chiloé Archipelago, all Chilean land south of the Bíobío River became free from Spanish rule. During this time, the Mapuche Nation also crossed the Andes mountains. They took control of areas that are now the Argentine provinces of Chubut, Neuquen, La Pampa, and Río Negro.

Becoming Part of Chile and Argentina

In the 1800s, Chile grew quickly. Chile set up a colony at the Strait of Magellan in 1843. They settled Valdivia, Osorno, and Llanquihue with German immigrants. They also gained land from Peru and Bolivia in the war of the Pacific. Later, Chile also took over Easter Island.

Because of this growth, Chile began to conquer Araucanía for two main reasons. First, the Chilean government wanted its land to be continuous. Second, Araucanía was the only place left for Chilean farming to expand.

Between 1861 and 1871, Chile added several Mapuche territories in Araucanía. In January 1881, after defeating Peru in battles, Chile continued its conquest of Araucanía.

Some historians say that the Mapuche population dropped from half a million to 25,000 in one generation. This was due to the occupation and the hunger and diseases that came with it. The conquest of Araucanía forced many Mapuches to leave their homes and search for food and shelter. Some scholars also say that the new state education during this time negatively affected traditional Mapuche education.

After the occupation, the economy of Araucanía changed. It went from raising sheep and cattle to farming and wood production. The Mapuches lost much of their land. This led to serious erosion because they continued to raise many animals in smaller areas.

Modern Challenges

Land disputes and conflicts still happen in some Mapuche areas. This is especially true in northern Araucanía, around Traiguén and Lumaco. In 2003, a special commission suggested big changes in how Chile treats its indigenous people. More than 80% of these people are Mapuche. The commission recommended officially recognizing the political and land rights of indigenous peoples. They also suggested efforts to promote their cultural identities.

While Japanese and Swiss companies are involved in Araucanía's economy, the two main forestry companies are Chilean-owned. In the past, these companies planted huge areas with non-native trees like Monterey pine, Douglas firs, and eucalyptus. Sometimes, they replaced native Valdivian forests.

Chile exports wood to the United States, mostly from this southern region. This trade is worth around $600 million each year. A conservation group called Stand.earth has worked to protect these forests. As a result, companies like Home Depot have agreed to change their buying rules to help protect native forests in Chile. Some Mapuche leaders want even stronger protections for the forests.

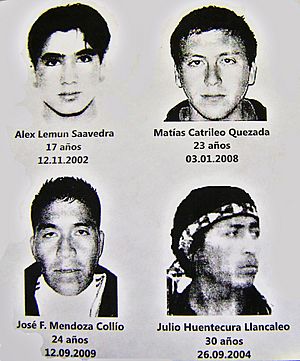

In recent years, crimes by Mapuche armed groups have been judged under anti-terrorism laws. These laws were first put in place by the military government of Augusto Pinochet to control political opponents. This law allows prosecutors to keep evidence from the defense for up to six months. It also lets witnesses hide their identity and give evidence from behind screens.

Oil drilling and fracking at the Vaca Muerta site in Neuquen, Argentina, have created waste dumps. This has polluted the environment near the town of Añelo. In 2018, the Mapuche sued Exxon, the French company TotalEnergies, and Pan American Energy over this pollution.

Mapuche Culture

When Europeans arrived, the Mapuche had a network of forts and defensive buildings. Ancient Mapuche also built ceremonial mounds, like those found near Purén. The Mapuche quickly learned to work with iron metal. (The Picunches already worked with copper). The Mapuche also learned horse riding and how to use cavalry in war from the Spanish. They also learned to grow wheat and raise sheep.

For 300 years, the Spanish colonies and the independent Mapuche regions lived side by side. During this time, the Mapuche developed a strong tradition of trading with the Spanish, Argentines, and Chileans. This trade was important for their silver-working tradition. Mapuche people made their jewelry from the many Spanish, Argentine, and Chilean silver coins they received. They also made headdresses with coins, called trarilonko.

Mapuche Languages

Mapuche languages are spoken in Chile and Argentina. The two main living branches are Huilliche and Mapudungun. While not directly related, some words from Quechua have influenced them. Experts believe only about 200,000 people in Chile speak Mapudungun fluently. The language gets little support in schools. However, in recent years, it has started to be taught in rural schools in the Bío-Bío, Araucanía, and Los Lagos Regions.

Mapuche speakers who also speak Chilean Spanish tend to use more impersonal pronouns when speaking Spanish.

Beliefs and Spirituality

A main idea in Mapuche beliefs is a creator called ngenechen. This creator has four parts: an older man, an older woman, a young man, and a young woman. They believe in worlds called the Wenu Mapu and Minche Mapu. Mapuche beliefs also include many spirits that live with humans and animals in nature. Daily events can lead to spiritual practices.

The most famous Mapuche ceremony is the Ngillatun, which means "to pray" or "general prayer." These ceremonies are often big community events that are very important spiritually and socially. Many other ceremonies are practiced, some for the public and some only for families.

The main groups of spirits in Mapuche beliefs are the Pillan and Wangulen (ancestor spirits), the Ngen (nature spirits), and the wekufe (evil spirits).

A very important person in Mapuche belief is the machi (shaman). This role is usually held by a woman. She learns from an older machi and has many qualities typical of shamans. The machi performs ceremonies to heal illnesses, ward off evil, influence weather, help with harvests, guide social interactions, and interpret dreamwork. Machis often know a lot about regional medicinal herbs. As nature has changed due to farming and forestry, this knowledge has decreased. However, the Mapuche people are working to bring it back in their communities. Machis also have a deep understanding of sacred stones and animals.

Like many cultures, the Mapuche have a deluge myth (epeu) about a great flood that destroys and recreates the world. This myth involves two opposing forces: Kai Kai (water, which brings death through floods) and Tren Tren (dry earth, which brings sunshine). In the flood, almost all people drown, and only one couple is left. A machi tells them they must give their only child to the waters. They do this, and it brings balance back to the world.

Part of Mapuche rituals involves prayer and animal sacrifice. These are needed to keep the balance of the world.

The Mapuche remember their long history of independence and resistance from 1540 (against the Spanish, then Chileans and Argentines). They also remember the treaties with the Chilean and Argentine governments in the 1870s. Memories, stories, and beliefs, often very local, are a big part of traditional Mapuche culture. This history of resistance continues today among some Mapuche. At the same time, many Mapuche in Chile identify as Chilean, and many in Argentina identify as Argentine.

Mapuche Textiles

One of the most famous Mapuche arts is their textiles (woven fabrics). The oldest evidence of textiles in southern South America comes from archaeological sites. These include the Pitrén Cemetery near Temuco, Chile, and the Alboyanco site in the Biobío Region, Chile. There is also the Rebolledo Arriba Cemetery in Neuquén Province, Argentina. Researchers have found fabrics made with complex techniques and designs, dating back to between AD 1300–1350.

Mapuche women were responsible for spinning and weaving. Knowledge of weaving techniques and local patterns was usually passed down within the family. Mothers, grandmothers, and aunts taught girls the skills they had learned from their elders. Women who were excellent weavers were highly respected. They helped their families economically and culturally. Weaving was so important that a man would pay a larger dowry for a bride who was a skilled weaver.

The Mapuche also used their textiles as an important extra product for trade. Many accounts from the 1500s describe them trading textiles with other indigenous peoples and with new Spanish settlements. This trade allowed the Mapuche to get goods they did not produce, like horses. The amount of fabric made by indigenous women and sold in Araucanía and northern Patagonia was very large. It was a vital source of income for families. Before European settlement, much of the fabric was clearly made for more than just family use.

Today, Mapuche fabrics are still used at home, as gifts, for sale, or for trade. Most Mapuche women and their families now wear clothes with modern designs made from factory-produced materials. However, they still weave ponchos, blankets, bands, and belts for regular use. Many fabrics are woven for trade, and this is an important source of income for families. Glazed pots are used to dye the wool. Many Mapuche women continue to weave fabrics following their ancestors' customs. They pass on their knowledge in the same way: within family life, from mother to daughter, and from grandmothers to granddaughters. This way of learning is based on watching and copying. Only rarely do students get direct instructions or help. Knowledge is passed on as the fabric is woven; the weaving and learning happen together.

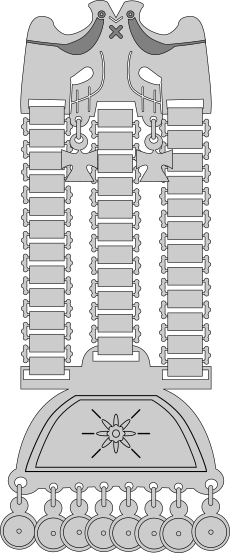

The Clava Hand-Club

The Mapuche use a traditional stone hand-club called a clava. It has a long, flat body. Another name for it is clava mere okewa. In Spanish, it can also be called a clava cefalomorfa. This club has special meaning and is a sign of importance carried by tribal chiefs. Many different types of clubs exist.

This object is linked to masculine power. It has a disk with a handle attached. The edge of the disk usually has a curved indentation. Often, a face is carved into the disk. The handle is round, usually wider where it connects to the disk.

Mapuche Silverwork

In the late 1700s, Mapuche silversmiths started making a lot of silver jewelry. This increase in silverwork might be linked to the 1726 parliament of Negrete. This meeting reduced fighting between the Spanish and Mapuches and allowed more trade between colonial Chile and the free Mapuches. With more trade, Mapuches began to accept silver coins as payment for their goods, usually cattle or horses. These coins, and silver coins from political agreements, were used as raw material by Mapuche metalsmiths (Mapudungun: rüxafe). Old Mapuche silver pendants often still had unmelted silver coins in them. This has helped modern researchers figure out when the pieces were made. Most of the Spanish silver coins came from mines in Potosí in Upper Peru.

The many different designs in silver jewelry show that they were made to identify different reynma (families), lof mapu (lands), and specific lonkos and machis. Mapuche silver jewelry also changed with fashion. However, designs linked to philosophical and spiritual ideas have not changed much.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Mapuche silverwork reached its peak in activity and artistic variety. All important Mapuche chiefs in the 1800s were believed to have at least one silversmith. By 1984, scholar Carlos Aldunate noted that there were no silversmiths left among the Mapuche.

Mapuche Literature

In the 1500s, Mapuche culture had an oral tradition, meaning stories were told, not written. Since then, a writing system for Mapudungun was created. Mapuche writings in both Spanish and Mapudungun have become popular. Today, Mapuche literature includes both oral traditions and writings in Spanish and Mapudungun. Famous Mapuche poets include Sebastián Queupul, Pedro Alonzo, Elicura Chihuailaf, and Leonel Lienlaf.

Mapuche and the Chilean State

After Chile became independent in the 1810s, other Chileans started to see the Mapuche as part of Chile. Before, they were seen as a separate people or nation. However, not everyone agreed. In the 1800s, Argentine writer and president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento shared his view:

Between two Chilean provinces (Concepción and Valdivia) there is a piece of land that is not a province. Its language is different, other people live there, and it can still be said that it is not part of Chile. Yes, Chile is the name of the country where its flag waves and its laws are obeyed.

Mapuche and the Argentine State

In the 1800s, Argentine authorities wanted to add the Pampas and Patagonia to their country. They knew the Puelmapu Mapuche had strong ties with Chile. This gave Chile some influence over the Pampas. Argentine authorities worried that if there was a war with Chile over Patagonia, the Mapuches would side with Chile.

Because of this, Estanislao Zeballos published a book in 1878 called La Conquista de quince mil leguas (The Fifteen Thousand League Conquest). This book was ordered by the Argentine Ministry of War. In it, Mapuches were presented as Chileans who would eventually return to Chile. So, Mapuches were indirectly seen as foreign enemies. This idea fit well with the plans of Nicolás Avellaneda and Julio Argentino Roca to expand into Puelmapu. However, calling Mapuches "Chileans" is not accurate because the Mapuche existed long before the modern state of Chile was formed. By 1920, Argentine Nationalism brought back the idea that Mapuches were Chileans. This was very different from what 20th-century scholars in Chile, like Ricardo E. Latcham and Francisco Antonio Encina, believed. They thought that the Mapuches came from east of the Andes before moving into what became Chile.

As late as 2017, Argentine historian Roberto E. Porcel wrote that many people who claim to be Mapuche in Argentina might actually be Mestizos (people of mixed heritage). He claimed they were encouraged by European supporters and "lack any right for their claims and violence." He also said they were "not most of them Araucanians" and "do not rank among our indigenous peoples."

Mapuche in Politics Today

In the 2017 Chilean general election, two Mapuche women were elected to the Chilean Congress for the first time. They were Aracely Leuquén Uribe from National Renewal and Emilia Nuyado from the Socialist Party.

Mapuche in Popular Culture

- The 2020 Chilean-Brazilian animated film Nahuel and the Magic Book features main characters, Fresia and Huenchur, whose clothing and tribe represent Mapuche culture.

- The video game Civilization VI includes the Mapuche as a playable group (in the Rise and Fall expansion). Their leader is Lautaro, a young Mapuche leader known for fighting against the Spanish in Chile. He developed tactics that the Mapuche continued to use for a long time.

- The novel "Inez of my Soul" by Isabel Allende tells the story of Pedro Valdivia's conquest of Chile. A large part of the book is about the Mapuche Conflict.

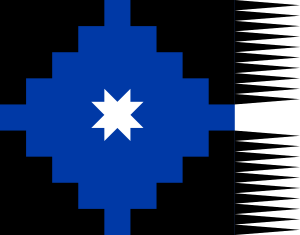

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pueblo mapuche para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo mapuche para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |