Tehuelche people facts for kids

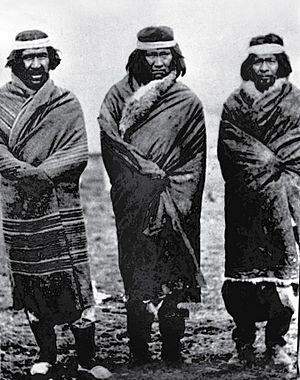

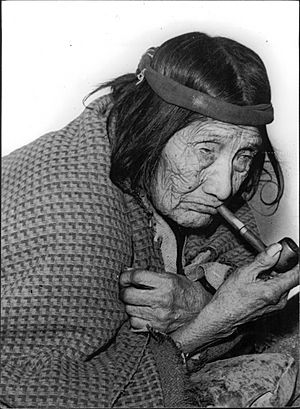

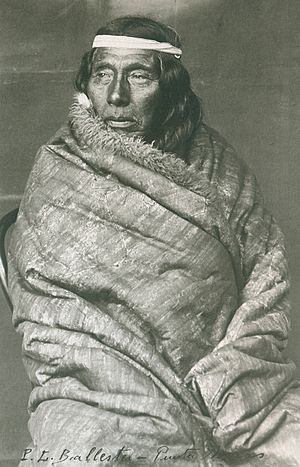

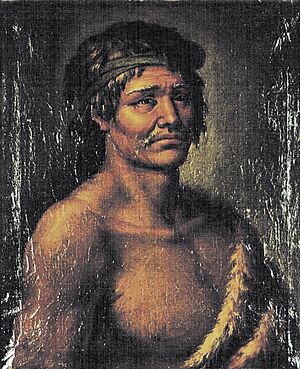

Mulato, a Tehuelche Chief.

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 27,813 (2010 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Argentina, Chile (historically) | |

| Languages | |

|

|

| Religion | |

| Animism (originally) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Haush, Mapuche, Selknam, Teushen |

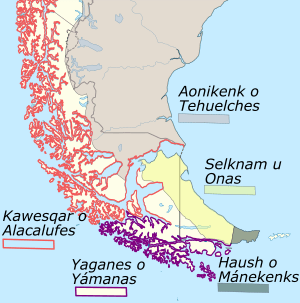

The Aónikenk people, also known as the Tehuelche, are an indigenous people from Patagonia in South America. Today, members of this group live near the borders of southern Argentina and Chile.

The name "Tehuelche" is sometimes used broadly. It can refer to several native groups from Patagonia and the Pampas region. These groups shared similar ways of life, lived close to each other, and had related languages.

Contents

What Does the Name Tehuelche Mean?

When Ferdinand Magellan's expedition arrived in 1520, they met native people in San Julian Bay. A historian on the trip, Antonio Pigafetta, called them "Patagoni."

Later, in 1535, another historian, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, wrote that the Spanish called them "Patagones" because of their "big feet." This idea was also shared by Francisco López de Gómara in 1552. Some people think Magellan might have been inspired by a dog-headed monster named "Pathogan" from a book.

The most common idea is that "Tehuelche" comes from the Mapuche language. It might mean "brave people," "rugged people," or "barren land people." Another idea is that it came from one of their groups, the Tueshens, combined with the Mapuche word "che," meaning "people."

How Tehuelche Groups Were Classified

It can be confusing to classify the native groups of the Pampas and Patagonia. Many different names were used for them. It's hard to create one clear classification for several reasons:

- Some groups died out.

- They lived across huge areas, making it hard for early explorers to meet everyone.

- They moved long distances with the seasons. This made Europeans think there were more people or that languages spread further than they did.

- The Mapuche people from the west also moved into the area. They mixed with and influenced many groups, changing their cultures. This is called the Araucanization of Patagonia.

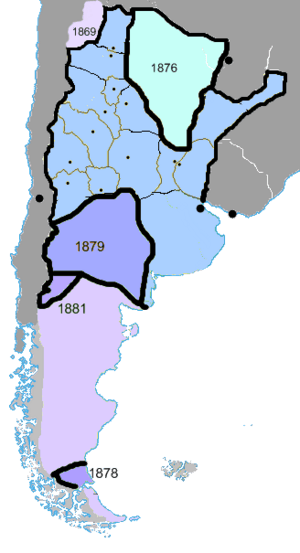

- Later, the Argentine Army's Conquest of the Desert almost wiped out these native communities.

Because of all these changes, experts don't always agree on how to classify the Tehuelche people.

In the 1800s, explorers like Ramón Lista and George Chaworth Musters called them "tsóneka" or "chonik." Most experts agree that the Chubut river divided them into two main groups: the "Southern Tehuelche" and the "Northern Tehuelche."

- The Southern Tehuelche lived south towards the Strait of Magellan.

- The Northern Tehuelche lived north towards the Colorado River (Argentina) and Rio Negro.

There's still some debate about whether a separate "Pampas" group existed and how they related to the Mapuche.

Different Ways to Classify Tehuelche Groups

Over time, different researchers tried to classify the Tehuelche people.

- Thomas Falkner (1774): An English Jesuit, Falkner described groups like the "Tehuelhets" or "Patagones." He said they lived from the Rio Negro to the Strait of Magellan.

- Milcíades Vignati (1936): Vignati suggested groups like the "Gününa-küne" (or "Tuelches") in the north, "Serranos" in the middle, and "Aônükün'k" (or "Patagones") in the south.

- Federico Escalada (1949): Escalada, a military doctor, divided the Tehuelche into five main groups based on their languages. He called their shared language "Ken."

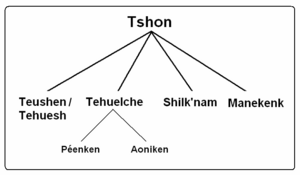

* Dry Land Tehuelche: * "Guénena-kéne": The northern group, living along rivers in North Patagonia. They spoke the Puelche language. * "Aóni-kénk": The southern group, from the Strait of Magellan to the Chubut River. They spoke the Tehuelche language. * "Chehuache-kénk": The western group, living in the valleys of the Andean Mountains. They spoke Teushen. * Island Tehuelche (on Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego): * "Selknam": Also known as the Onas, living in the northern part of the island. * "Man(e)kenk": Also known as the Haush, living in the eastern part of the island.

- Rodolfo Casamiquela (1960s-1980s): This Argentine historian and paleontologist also classified the Tehuelche. He suggested:

* "Southern Southern Tehuelche" or "Aónik'enk": Nomadic hunters from the Strait of Magellan to the Santa Cruz River. * "Northern Southern Tehuelche" or "Mech'arn": Lived around the Chico and Chalía rivers in Santa Cruz. * "Southern Northern Tehuelche": Also called "Pampas" or "mountain-dwellers." They lived between the Chubut and Río Negro rivers. * "Northern Northern Tehuelche": Included the "Puelches" from north of Neuquén and the "Querandí" group.

Languages of the Tehuelche People

The different groups called "Tehuelche" spoke several languages. Experts have different ideas about how many there were and how they were related. Most agree on six main languages: Teushen, Aoenek’enk, Selknam, Haush, Gününa küne, and Querandí.

The Aonekkenk language is closely related to Teushen. These are also related to the languages of Tierra del Fuego (Selknam and Haush). The Gününa küne language is more distantly related.

Until the 1800s, these languages were known:

- The Gününa küne group spoke Puelche (also called Gününa yajüch). Its relationship to other languages is still debated.

- The "Tshoneka centrales" spoke a language called Pän-ki-kin (Peénkenk). They lived in Neuquén, Río Negro, and northern Chubut.

In central Patagonia, there was an old language called Tehuesh (or Teushen). It was a mix between Penkkenk and Aonekkenk. This language was slowly replaced by Aonekkenk. Many place names in the central plateau still come from Tewsün roots. For example, the name of the Chubut Province comes from the word "chupat."

Today, the Aonekken ("people of the South") speak the Tehuelche language. This is the most studied language of the group and the only one still used. Some people are working to bring the language back to life through a program called "Kkomshkn e wine awkkoi 'a'ien" ("I am not ashamed of speaking Tehuelche").

Studying the Gününa Yajüch Language

Many people have studied the Gününa yajüch language:

- In 1864, Hunziker recorded words and phrases.

- In 1865, explorer Jorge Claraz collected names, words, and sentences while traveling.

- In 1913, Lehmann Nitsche used this data to compare Tehuelche languages.

- In 1925, Harrington collected words from bilingual speakers. He published them in 1946, saying the speakers called their language Gününa yájitch or Pampa.

- In the 1950s, Casamiquela collected words, songs, and prayers from elders.

- In 1960, Ana Gerzenstein studied its sounds.

- In 1991 and 2005, José Pedro Viegas Barros described its grammar and sounds.

Sadly, Puelche is now an extinct language. The last speaker, José María Cual, died in 1960.

Tehuelche Social Organization

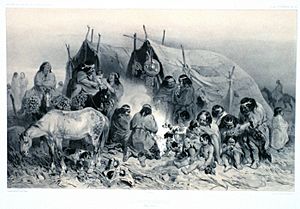

Tehuelche groups were nomadic, meaning they moved around. They usually followed specific paths, often moving from west to east and back. Each season, they had special places to set up their camps. They called these aik or aiken, and the Spanish called them tolderías.

Each group was made up of different families. They had their own hunting and gathering areas. The borders of these areas were marked by natural features like hills or hollows. If a group needed resources from another group's land, they had to ask permission. If they didn't, it could lead to war.

Tehuelche families were very organized. Men were usually the leaders, and women had a different role. Fathers would often offer their daughters for marriage in exchange for goods. A man could have two or three wives, depending on his standing in the group.

Tehuelche Beliefs

The Tehuelche people did not have a formal religion with churches or priests. However, they had many beliefs, myths, and rituals. Shamans were important figures who told stories and performed healing with the help of spirits.

The Tehuelche believed in many Earth spirits. They also believed in a supreme god, Kóoch, who created the world but did not interfere in daily life. One myth says Kóoch brought order to the world from chaos. The Selknam people, who were related, had a similar myth about a creator god named Kénos'. In Tehuelche myths, a hero named El-lal created humans and taught them how to use bows and arrows. The Tehuelche also believed in an evil spirit called Gualichu.

History of the Tehuelche

Ancient Times

The ancestors of the Tehuelche likely created the amazing rock art at Cueva de las Manos. This art was made between 13,000 and 9,000 years ago, and up until about 700 A.D.

Around 6,000 years ago, a new style of tools appeared, called the Toldense industry. These included spear points and knives. Later, between 7,000 and 4,000 B.C., the Casapedrense industry developed, with more stone tools made from thin pieces. This suggests they became very good at hunting guanaco, which continued to be important for the Tehuelche.

From these ancient times until Europeans arrived in the early 1500s, the Tehuelche were hunter-gatherers. They moved with the seasons to follow guanaco herds. In winter, they stayed in lower areas like meadows and lake shores. In summer, they moved to the central plateaus of Patagonia or the Andes mountains. Mount Fitz Roy was one of their sacred places.

European Arrival

On March 31, 1520, Ferdinand Magellan's Spanish expedition landed in San Julián Bay. Here, they met Tehuelche groups. The expedition's scribe, Antonio Pigafetta, called them "Patagones." He described them as a mythical tribe of Patagonian giants.

Before meeting them, the explorers were amazed by their large footprints. The animal furs they wore as shoes made their feet look even bigger. Europeans in the 1500s were shorter, averaging about 165 cm (5 feet, 5 inches). Some reports said Patagonian men were over 2 meters (6 feet, 7 inches) tall, while others said around 183 cm (6 feet). So, the Europeans might have called them "Patones" (meaning 'large footed').

The arrival of the Spanish changed the lives of native peoples. Diseases like measles, smallpox, and the flu spread among the Tehuelche. These diseases greatly reduced their population, especially the northern Gennakenk group.

Influence from the Mapuche People

Starting in the 1700s, there was a lot of trade between the native people of the Pampas, Northern Patagonia, and the Andes. Important trade fairs, like the "Poncho fairs," were held. Here, people exchanged goods like livestock, farm products, and clothing such as ponchos. These trade fairs led to cultural exchanges and movements of people between different groups, including the Tehuelche, Ranquel, and Mapuche people.

While trade started peacefully, the Mapuche began to have a big cultural influence on the Tehuelche. This is known as "Mapuchization" or "Araucanization of Patagonia". Many Tehuelche and Ranquel people adopted Mapuche customs and their language. In turn, the Mapuche adopted some Tehuelche ways of life. Over time, the differences between the groups became less clear. Their descendants often call themselves Mapuche-Tehuelche people.

In the early 1700s, Chief Cangapol was a very important leader. His people were known as the "Mountain Pampas." They even teamed up with the Mapuche to attack Buenos Aires in 1740.

There were also conflicts between different native groups. By 1820, there was fighting between the Patagones and Pehuenches. Later, in 1828, a royalist army attacked Tehuelche groups.

The Tehuelche people south of the Río Negro had a female chief named María la Grande. Her successor, Casimiro Biguá, was the first Tehuelche chief to sign treaties with the Argentine government. His sons, Papón and Mulato, later lived on a reserve in southern Chile.

The Tehuelche also lived alongside Welsh immigrants who settled in Chubut in the late 1800s. Their relationship was generally peaceful.

Before they had horses, Tehuelche life was similar to the Ona people of Tierra del Fuego. But after 1570, when the Spanish introduced horses, everything changed. Horses became very important for their daily lives. Like the native groups of the North American Great Plains, the Tehuelche used horses to hunt guanaco and rhea (ñandú or choique). They also hunted South Andean deer, deer, Patagonian mara, and even puma and jaguar. They ate some plants too, and later learned to farm a little. Their groups usually had between 50 and 100 members.

The horse, especially the mare, became a main part of the Tehuelche diet, even more important than guanacos. The Selknam of Tierra del Fuego did not rely on horses as much. The new mobility from horses changed their traditional territories and movement patterns. Before the 1600s, they mostly moved east-west to hunt guanacos. But with horses, they started moving north-south, creating large trade networks.

Forced Exhibitions

In the late 1800s, some Tehuelche people were taken from their homes and displayed against their will in countries like Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, France, and England. For example, a chief named Pitioche, his wife, and child were captured and exhibited. These sad events are described in the book Zoológicos humanos (Human Zoos).

Reservations in Santa Cruz

To help gather the Tehuelche tribes, the Camusu Aike reservation was created in Santa Cruz Province in 1898.

In 1922, President Hipólito Yrigoyen created more reserves. However, some of these were later taken away from the Tehuelche people.

Famous Tehuelche People

- Inacayal

- Salpul

Tehuelche People Today

An old census from 1966-1968 showed that only a few Tehuelche descendants still spoke the Tehuelche language. The groups who kept most of their culture lived in the central plateau of Santa Cruz Province, though they had mixed with other groups.

The 2004-2005 "Complementary Survey of Indigenous Peoples" found that 4,351 people in Chubut and Santa Cruz Provinces were first-generation descendants of Tehuelche people. Another 1,664 considered themselves Tehuelche in Buenos Aires, and 4,575 in other parts of Argentina. In total, 10,590 people in Argentina identified as Tehuelche.

The 2010 National Population Census in Argentina found 27,813 people who identified as Tehuelche across the country. Many live in Chubut, Buenos Aires Province, Santa Cruz, and Río Negro.

Today, there are Tehuelche settlements in Santa Cruz Province:

- Camusu Aike Territory: Northwest of Río Gallegos.

- Lago Cardiel Lot 6: Near Gobernador Gregores City.

- Lago Cardiel Lot 28 bis: Also near Gobernador Gregores City.

- Cerro Índice: Southeast of Viedma Lake.

- Copolque (or Kopolke): Near Las Heras.

Some people in these settlements speak Aonekko 'a'ien, but most speak Spanish.

There are also two reservations in Chubut Province:

- El Chalía: In the Río Senguer Department, with about 80 residents.

- Loma Redonda: Between Río Mayo and Alto Río Senguer, with about 30 residents.

Most people in these Chubut reservations speak Spanish. Some are bilingual in Spanish and Mapudungun. In 1991, only two elderly women remembered the Aonek'o 'a'ien language there.

Since 1995, Argentina's National Institute of Indigenous Affairs (INAI) has recognized the legal status of native communities. This includes Tehuelche communities in Santa Cruz and mixed Mapuche-Tehuelche communities in Chubut, Río Negro, Buenos Aires, and Santa Cruz.

Mapuche-Tehuelche Communities

In Chubut Province, there are mixed communities of Mapuche and Tehuelche people. They call themselves Mapuche-Tehuelche. Some of these communities include:

- Huanguelen Puelo Community (Puelo Lake)

- Motoco Cárdenas Community (Puelo Lake)

- Cayún Community (Puelo Lake)

- Vuelta del Río Community (Cushamen Indigenous Reserve)

- Emilio Prane Nahuelpan Community (League 4)

- Enrique Sepúlveda Community (Buenos Aires Chico)

- Huisca Antieco Community (Alto Río Corinto)

- Blancura y Rinconada Community

- Blancuntre-Yala Laubat Community

- Traquetren Community

- Auke Mapu Community

- Pocitos de Quichaura Community

- Paso de Indios Community (Paso de Indios)

- Katrawunletuayiñ Community (Rawson)

- Tramaleo Loma Redonda Community

- Laguna Fría-Chacay Oeste Community

- Mallin de los Cuales Community (Gan Gan)

- Mapuche Tehuelche Pu Fotum Mapu Community (Puerto Madryn)

- Esteban Tracaleu Community

- Loma Redonda – Tramaleu Community

- Taguatran Community

- Tewelche Mapuche Pu Kona Mapu Community (Puerto Madryn)

- Mapuche Tehuelche Indigenous group "Gnechen Peñi Mapu" (Puerto Madryn)

- Sierras de Huancache Community

- Bajada de Gaucho Senguer Community

- Willi Pu folil Kona Community

- "Namuncurá-Sayhueque" Community (Gaiman)

- Mariano Epulef Community

- El Molle Community

- Nahuel Pan Community

- Río Mayo Community (Mayo River)

- Himun Community Organization

- Rincón del Moro Community

- Escorial Community

- Rinconada Community

- Cushamen Centro Community

- Mapuche Tehuelche Trelew Community (Trelew)

- Pampa de Guanaco Community

- Sierra de Gualjaina Community

- Bajo la Cancha Community

- Arroyo del Chalía Indigenous Community

- Caniu Community (Buenos Aires Chico – El Maitén, Chubut)

There are also four urban Mapuche-Tehuelche communities in Santa Cruz: in Caleta Olivia (Fem Mapu), Gallegos River (Aitué), in Río Turbio (Willimapu), and in Puerto Santa Cruz (Millanahuel).

The Cushamen indigenous reserve in Chubut was created in 1889. It was meant for Chief Miguel Ñancuche Nahuelquir's tribe, who were moved from the Neuquén mountains. This reserve covers a large area and is home to 400 Mapuche-Tehuelche families.

Tehuelche in Chile

The Tehuelche group is almost gone in Chile. In 1905, a smallpox outbreak killed Chief Mulato and others in his tribe near Punta Arenas. The few survivors went to Argentina, possibly to the Cumusu Aike reserve. Their memory lives on in the name Villa Tehuelches, a town in Chile.

See also

In Spanish: Tehuelches para niños

In Spanish: Tehuelches para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |