Cueva de las Manos facts for kids

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

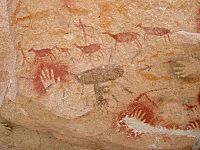

Hands, stenciled at the Cave of the Hands

|

|

| Official name | Cueva de las Manos, Río Pinturas |

| Location | Santa Cruz, Argentina |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Inscription | 1999 (23rd Session) |

| Area | 600 ha (1,500 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 2,331 ha (5,760 acres) |

Cueva de las Manos means Cave of the Hands in Spanish. It is a famous cave in Santa Cruz, Argentina. This amazing place is known for its hundreds of ancient paintings of hands. These handprints were made by spraying paint onto the rock walls.

The artwork was created by people who lived there long ago, between about 7,300 BC and 700 AD. This time is known as the Archaic period in South America, before Christopher Columbus arrived. Scientists figured out the age of the paintings by studying bone pipes used for spraying paint. They also used methods like radiocarbon dating and looking at layers of rock and dirt.

Many experts believe this site shows us the best evidence of early hunter-gatherer groups in South America. A famous Argentine archaeologist, Carlos J. Gradin, and his team studied the cave for 30 years, starting in 1964. Cueva de las Manos is now a National Historic Monument in Argentina. It is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which means it's important for everyone to protect.

Contents

Where is the Cave of the Hands?

Cueva de las Manos is not just one cave. It's a main cave and many other rock art spots around it. The cave sits at the bottom of a tall cliff in the Pinturas River Canyon. This area is a remote part of Patagonia.

It's about 165 kilometers (103 mi) south of Perito Moreno, a town in northwest Santa Cruz. The cave is part of both Perito Moreno National Park and Cueva de las Manos Provincial Park.

What was the climate like?

Long, long ago, when ancient people lived here, the canyon had a special climate. It was a bit warmer and wetter, allowing grasslands to grow. Many animals lived there, and people found plants for food and medicine.

Today, the area is a cold and dry steppe, like a grassy plain. It doesn't get much rain. But the canyon walls help block the strong winds, making winters a bit less harsh. The average temperature is 8 °C (46 °F). It can get as hot as 38 °C (100 °F) in summer and as cold as −10 °C (14 °F) in winter.

How to visit the cave

In ancient times, people reached the canyon through paths from higher up. Today, there are gravel roads leading to the site. One road is 46 km (29 mi) from the south, near Bajo Caracoles. There are also two roads from Ruta 40 further north. One of these ends with a 4 km (2.5 mi) walking trail.

History of the Ancient Artists

When people lived at Cueva de las Manos, the Pinturas and Deseado Rivers flowed into the Atlantic Ocean. These rivers brought water for large groups of guanacos, which are like small llamas. This made the area a great place for ancient people to live and hunt.

Over time, as ice fields melted, the rivers changed direction. The water levels in the Pinturas and Deseado rivers dropped. This led to people slowly leaving the Cueva de las Manos area.

Archaeologists have found old tools here, like spear points and bola stones. They also found bones from guanacos, pumas, foxes, and birds. Guanacos were the main food source for these people. They hunted them using bolas, ambushes, and by driving the animals into narrow areas. The cave art actually shows these hunting methods.

The people living in Patagonia long ago were hunter-gatherers. This means they hunted animals and gathered plants for food. Their artwork clearly shows this way of life. Scientists also found obsidian near the cave, which is not natural to the area. This suggests that these ancient groups traded with people from far away.

Around 7,500 BC, Cueva de las Manos became an important stop for nomadic groups. They moved seasonally between the Pinturas Canyon, the high plains, and the forests near the Andes mountains. They followed the seasons to find the best plants and to hunt newborn guanacos, whose furs were very valuable. The best time to find newborn guanacos near the cave was around November.

The earliest rock art at the site was made around 7,300 BC. Cueva de las Manos has the oldest art of this kind in the region. The cave was last used by people around 700 AD. These last cave dwellers might have been ancestors of the Tehuelche tribes.

Modern studies and protection

The site was first written about in 1941 by an Italian explorer, Father Alberto Maria de Agostini. Later, in 1949, the La Plata Museum sent an expedition to study it. But the most important research began in 1964 with archaeologist Carlos Gradin. His work helped us understand the different styles of art in the cave.

Cueva de las Manos became a National Historic Monument in Argentina in 1993. In 1999, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This means it's recognized as a very important place for all of humanity. In 2015, an environmental group bought the land. Then, in 2018, it became a provincial park. By 2020, the land was given to the state to protect it even more.

The Cave's Structure

The cave is carved into the canyon walls, which are made of volcanic rocks. These rocks formed about 150 million years ago during the Jurassic period. The Pinturas River slowly carved out the cave and overhangs over millions of years. The river wore away softer rocks, leaving the stronger ones behind. The cave itself is at a crack in the rock face that the river eroded more deeply.

The main cave is about 20 m (66 ft) deep. It also includes two rock overhangs and the walls on either side of the entrance. The entrance faces northeast and is about 15 m (50 ft) tall and 15 m (50 ft) wide. The paintings inside the cave cover a large area, about 60 m × 200 m (200 ft × 650 ft). The cave floor slopes upwards, so the height inside gets lower, eventually reaching about 2 m (6 ft 7 in).

Amazing Artwork

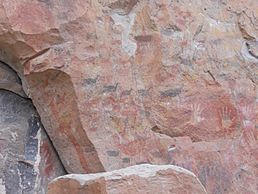

Cueva de las Manos is famous for its hundreds of hand paintings. These hands are stenciled in many layers on the rock walls. This art is some of the most important in the Americas, and the most well-known rock art in the Patagonia region. The art dates from about 7,300 BC to 700 AD. Some experts believe these are the oldest known cave paintings in South America.

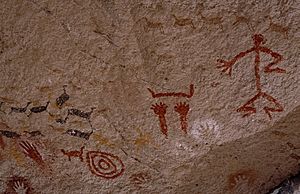

The artwork covers the inside of the cave and the cliffs outside. The paintings show three main things: people, the animals they hunted, and human hands. The people depended on hunting guanacos to survive, and you can see how important these animals were in their art.

Different groups of people lived in the cave over thousands of years. Scientists can tell the age of the paintings by studying bone pipes used to spray paint. They also use radiocarbon dating on the paint itself and look at the layers of rock. Chemical tests on the paints and studying how the art styles overlap prove the art is real. Experts say it's the "best material evidence of early hunter-gatherer groups in South America."

Art styles and forms

The earliest paintings in the cave looked very realistic, like the actual animals or people. Over time, the art became more abstract, meaning it looked less like real life and more like symbols.

There are over 2,000 handprints in and around the cave. Most of them are "negative" prints, made by spraying paint around a hand placed on the wall. There are many more left hands than right hands. This suggests that most artists held the spray pipe with their right hand. Some handprints are missing fingers. This could be from injuries or even a form of sign language.

The rock walls have different depths, which changes how the art looks depending on where you stand. Many handprints are painted on top of each other, creating layers of color. But there are also many single hands placed carefully.

Besides hands, you can see drawings of people, guanacos, rheas (large birds), wild cats, deer, and other animals. There are also geometric shapes, zigzag patterns, sun symbols, and hunting scenes. The hunting scenes show different ways people hunted, like driving animals into traps. You can also see red dots on the ceilings. These were probably made by dipping hunting bolas in paint and throwing them upwards.

The animals shown in the artwork, especially the guanacos, still live in the area today. The repeated scenes of hunters surrounding guanacos suggest this was their main hunting method.

What does the art mean?

We don't know much about the culture of these artists, except for their tools and what they hunted. Modern researchers can only guess about their daily life and beliefs. But the fact that so many people added to the artwork for thousands of years shows the cave was very important to them. The art tells us that these people had a symbolic side to their culture.

The artwork helped people remember their history and traditions. Earlier groups influenced later ones, creating a story that lasted for thousands of years. The art shows important parts of their hunter-gatherer life, like the birth cycles of guanacos and group hunting. The cave was also a special place where groups returned seasonally to create art, almost like a ritual.

Why did they make the art?

The exact reason for this art is unknown. Some think it might have been for religious ceremonies or just for decoration. Some scholars believe the handprints show a human desire to be remembered. But others disagree, suggesting it might be linked to ancient shamanism or ceremonies we'll never fully understand.

Another idea is that the art marked territories between different groups. It might have also been part of "hunting magic," meant to help them find more animals to hunt. No matter the exact reason, the fact that so many people gathered here to create art for such a long time shows its huge cultural importance.

What materials did they use?

The artists used different minerals to make their paints. They used iron oxides for reds and purples, kaolin for white, and a mineral called natrojarosite for yellow. They also used manganese oxide for black and sometimes copper oxide for green. Other materials found include haematite, goethite, quartz, and calcium oxalate. They used Gypsum to help the paints stick better to the rock.

Different art styles over time

Experts have divided the art into four main styles: A, B, B1, and C. These are also known as Río Pinturas I, II, III, and IV. The first two styles help us see the difference between guanacos painted in motion (style A) and those painted standing still (style B).

Style A: The earliest art

Style A (Río Pinturas I) is the oldest art in the cave, from around 7,300 BC. This style is very realistic and shows movement. It includes colorful, active hunting scenes and negative handprints. The artists used the natural bumps and grooves in the rock to create parts of their art, like showing ravines in the landscape. The hunters in these scenes likely traveled long distances and used ambush tactics to hunt guanacos.

Since 2010, Style A has been divided into five smaller groups based on color. A1 (Ochre series) uses mostly ochre and some red. A2 (Black series) is mainly black with some dark purple. A3 (Red series) uses mostly red. A4 (Purplish/Dark Red series) uses purplish red and dark red. A5 (White/Yellow series) uses mostly white and yellow-ochre. In terms of layers, A2 usually covers A1, A3 covers A1 and A2, and so on. A1 is the oldest, and A5 is the youngest.

The Black series (A2) brought new ideas to the art. It introduced views from above and showing important figures larger. It also used contrasting colors like black and dark purple to make different parts of the art stand out. Many of these ideas influenced hunting scenes until about 5,400 BC.

Style A ended around 4,770 BC, likely because of a big eruption of the Hudson volcano. This eruption probably caused people to leave the Río Pinturas area.

Styles B and B1: New groups, new art

A new group of people created the art of styles B (Río Pinturas II) and B1 (Río Pinturas III). This period lasted from about 5,000 BC to 1,300 BC. Instead of lively hunting scenes, you see guanacos standing still, often with large bellies, possibly pregnant. These pregnant guanacos were first shown in the Black series of Style A. Style B also includes large groups of layered handprints (about 2,000 of them!) in many colors. You might also see rare prints of human and animal footprints.

In Style B1, the shapes become simpler and more stylized. This group includes hand stencils, bola marks, and patterns made of dots.

Style C: Abstract designs

Style C, or Río Pinturas IV, began around 700 AD. This is the last art style found in the cave. It focuses on abstract geometric shapes. You'll see simple outlines of animals and people, along with circles, zigzag patterns, dots, and more hands layered on top of older ones. The main color used in this style is red.

Importance and Protection

Every February, the nearby town of Perito Moreno holds a festival to celebrate the caves called Festival Folklórico Cueva de las Manos.

Many tourists from all over the world visit the cave. Since it became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999, the number of visitors has quadrupled. In 2020, about 8,000 people visited each year. This popularity brings new challenges for protecting the site. The biggest threat is graffiti, along with people taking pieces of painted rock or touching the paintings.

To protect the cave, it has been fenced off, and a boardwalk was built to guide visitors. Visitors must go with a tour guide. There are also walking trails, a guide lodge, and a parking lot. Experts from Argentina's National Institute of Anthropology and Latin American Thought (INAPL) helped build these facilities. Programs are also in place to teach tourists and local guides about protecting the site. The rock art is even being recorded in 360° video for a virtual reality experience.

Despite these efforts, some people say the local and national governments, and UNESCO, need to do more to protect the site. They say more staff and a permanent archaeologist are needed at the cave.

See also

In Spanish: Cueva de las Manos para niños

In Spanish: Cueva de las Manos para niños