Jules Dumont d'Urville facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jules Dumont d'Urville

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 23 May 1790 Condé-sur-Noireau, France |

| Died | 8 May 1842 (aged 51) Meudon, France |

| Buried |

Montparnasse Cemetery

|

| Allegiance | France |

| Service/ |

Navy |

| Rank | Rear Admiral |

| Commands held | Astrolabe |

| Spouse(s) | Adèle Pepin |

| Relations | Gabriel Charles François Dumont |

Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville (born May 23, 1790 – died May 8, 1842) was a famous French explorer and naval officer. He explored many parts of the world, including the southern and western Pacific, Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica.

Jules was also a botanist (someone who studies plants) and a cartographer (someone who makes maps). He discovered many new plants and seaweeds. Some places, like D'Urville Island in New Zealand, are named after him.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Jules Dumont d'Urville was born in Condé-sur-Noireau, a town in Lower Normandy, France. His father passed away when Jules was only six years old. After this, his uncle, the Abbot of Croisilles, Calvados, helped raise him.

From a young age, Jules was very smart and loved to learn. His uncle taught him Latin, Greek, and philosophy. When he was older, Jules studied at a school in Caen. There, he read many books about famous explorers like Bougainville, Cook, and Anson. These stories made him dream of exploring the world himself.

At 17, Jules wanted to join the navy. He tried to get into a special school but didn't pass the physical tests. So, he decided to simply enlist in the navy instead.

In 1807, Jules joined the Naval Academy in Brest. He was a quiet and serious student, more interested in learning than in playing around. He quickly became a top student.

During this time, the French navy was not as strong as the British navy. Many French ships were stuck in port. This gave Jules a lot of time to study. He learned many languages, including English, German, Italian, Russian, Chinese, and even Hebrew. Later, during his travels, he would learn many different dialects from the islands of Polynesia and Melanesia.

While ashore in Toulon, he also studied botany (plants) and entomology (insects). He would go on long trips into the hills to collect specimens.

In 1814, Jules finally got to sail in the Mediterranean Sea. In 1815, he married Adèle Pepin.

Discovering the Venus de Milo

In 1819, Jules sailed on a ship called Chevrette. Their mission was to map the islands of Greece. While they were near the island of Milos, a local French official told Jules about a marble statue that had just been found.

This statue, now known as the famous Venus de Milo, was very old and beautiful. Jules immediately saw how important it was. He wanted to buy it, but his ship was too small to carry such a large statue. So, he wrote to the French ambassador in Constantinople to tell him about the discovery.

Thanks to Jules's quick thinking, the French ambassador bought the statue. It was then brought to France and placed in the Louvre Museum in Paris. For his part in this discovery, Jules was made a Chevalier (knight) of the Légion d'honneur and promoted to lieutenant.

Voyage of Coquille

After his trip on Chevrette, Jules met another naval officer named Louis Isidore Duperrey. They both wanted to explore the Pacific Ocean. France had lost some of its power in that area during the Napoleonic Wars. They hoped to regain some influence by exploring new lands.

On August 11, 1822, a ship called Coquille sailed from Toulon. Its goal was to gather scientific and strategic information about the Pacific. Duperrey was the commander, and Jules was his second-in-command.

During this voyage, Jules made an amazing discovery: the Adélie penguin. He named it after his wife, Adèle.

The ship returned to France in March 1825. Jules and the ship's doctor, René-Primevère Lesson, brought back a huge collection of animals and plants. They had collected specimens from the Falkland Islands, Chile, Peru, the Pacific islands, New Zealand, New Guinea, and Australia.

Jules was now 35 years old and had collected more than 3,000 plant species. About 400 of these were completely new to science! He also brought back over 1,200 insect specimens, including 300 new species. Scientists like Georges Cuvier and François Arago praised his work.

Jules also left his mark on New Zealand's plant life. Several plants and seaweeds are named after him, such as the Durvillaea seaweed and the Hebe urvilleana shrub.

First Voyage of Astrolabe

Soon after returning from the Coquille voyage, Jules suggested a new expedition. He wanted to be the commander this time. His idea was approved, and the ship Coquille was renamed Astrolabe. This was in honor of one of the ships of another famous explorer, La Pérouse.

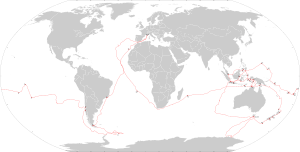

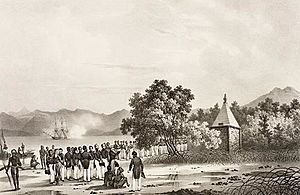

The Astrolabe left Toulon on April 22, 1826. It was a journey around the world that would last almost three years.

During this trip, the Astrolabe sailed along the coast of southern Australia. Jules created new, detailed maps of the South Island of New Zealand. He explored the Marlborough Sounds and sailed through the tricky French Pass. He also mapped D'Urville Island, which had previously been thought to be part of the mainland.

The ship then sailed up the east coast of New Zealand's North Island, making more detailed maps. After getting supplies in the Bay of Islands, they sailed to Tonga.

The Astrolabe also visited Fiji. Jules then made the first maps of the Loyalty Islands (part of New Caledonia). He explored the coasts of New Guinea. A very important discovery was finding the site where La Pérouse's ships had been shipwrecked in Vanikoro (part of the Solomon Islands). Jules collected many remains from La Pérouse's boats.

The journey continued with mapping parts of the Caroline Islands and the Moluccas. The Astrolabe returned to Marseille on March 25, 1829. They brought back a huge amount of maps and scientific collections. These discoveries greatly influenced how scientists understood these regions. After this expedition, Jules created the terms Micronesia and Melanesia to describe different island groups in the Pacific.

Jules's health was not good after these long voyages. He suffered from kidney and stomach problems. He also had painful attacks of gout.

After a short time with his family, Jules returned to Paris. He was promoted to captain and put in charge of writing a report about his travels. This report was published in many volumes between 1832 and 1834.

Second Voyage of Astrolabe

In 1837, Jules suggested another expedition to the Pacific. King Louis-Philippe approved the plan. However, the King added a new goal: the expedition should try to reach the South Magnetic Pole and claim it for France. This made France part of a big international race to explore the polar regions, along with the United States and the United Kingdom.

Jules was not very interested in polar exploration at first. He preferred warmer places. But he soon realized this was a chance to achieve something very important. Two ships, Astrolabe and Zélée (commanded by Charles Hector Jacquinot), were prepared for the voyage in Toulon.

First Contact with Antarctica

The Astrolabe and Zélée sailed from Toulon on September 7, 1837. Their goals included exploring the Weddell Sea, passing through the Strait of Magellan, visiting new British colonies in Western Australia, and sailing to New Zealand.

Early in the trip, some crew members got into trouble in Tenerife. There were also problems with food, and some crew members got sick. In November, the ships reached the Strait of Magellan.

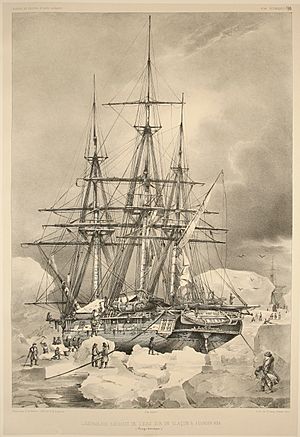

On January 1, 1838, the ships found themselves stuck in a lot of ice. For the next two months, Jules tried hard to find a way through the ice. The crew worked for five days straight to clear a path.

After reaching the South Orkney Islands, the expedition headed towards the South Shetland Islands and the Bransfield Strait. They found land that was only roughly mapped. Jules named some of it Terre de Louis-Philippe (now called Graham Land).

Conditions on board became very difficult. Many crew members showed signs of scurvy, a serious illness caused by lack of Vitamin C. The ships were also smoky and smelly. By the end of February 1838, Jules decided they could not go further south. He steered the ships towards Talcahuano, in Chile, where the sick crew members could get help.

Pacific Explorations

During their months in the Pacific, the ships visited many islands in Polynesia. The crews often socialized with the islanders.

While sailing from the East Indies to Tasmania, some crew members died from tropical fevers and dysentery. For Jules, the hardest moment was when he received a letter from his wife. It told him that his second son had died from cholera. His wife begged him to come home. Jules's own health was also getting worse with more attacks of gout and stomach pains.

On December 12, 1839, the two ships arrived in Hobart, Tasmania. The sick were treated there. Jules met John Franklin, the Governor of Tasmania and a famous Arctic explorer. Franklin told him that American expedition ships were in Sydney, also planning to sail south.

Jules decided to continue his Antarctic journey with only the Astrolabe, but Captain Jacquinot convinced him to take both ships. The Astrolabe and Zélée left Hobart on January 1, 1840. Jules's plan was simple: head south if the wind allowed.

Reaching Antarctica

On January 16, 1840, at 60°S latitude, they saw their first iceberg. Two days later, the ships were surrounded by ice. On January 20, the expedition crossed the Antarctic Circle. This was a big moment, celebrated like crossing the Equator. That same afternoon, they sighted land!

The two ships slowly sailed west, following ice walls. On January 22, some crew members landed on a small island near the icy coast. They raised the French flag. Jules named the archipelago Pointe Géologie and the land beyond it Adélie Land. He named Adélie Land after his wife.

In the following days, the expedition continued west. They also did experiments to find the approximate position of the South Magnetic Pole. On January 30, 1840, they saw the American ship Porpoise, but they couldn't communicate. On February 1, Jules decided to turn north towards Hobart.

They arrived in Hobart 17 days later. There, they saw the ships of James Clark Ross’s British expedition to Antarctica, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus.

On February 25, the ships sailed to the Auckland Islands. They took magnetic measurements and left a plate announcing their discovery of the South Magnetic Pole. They returned to France via New Zealand, the Torres Strait, Timor, Réunion, and Saint Helena. They arrived back in Toulon on November 6, 1840. This was the last French exploration expedition of its kind.

Return to France

When Jules returned, he was promoted to rear admiral. He also received the Gold Medal of the Société de Géographie (Geographical Society of Paris) and later became its president. He then started writing the report of his expedition, called Voyage au pôle Sud et dans l'Océanie. This huge report was published in 24 volumes, plus seven more volumes with illustrations and maps.

Tragic Death and Legacy

On May 8, 1842, Jules Dumont d'Urville and his family were on a train from Versailles to Paris. The train's engine went off the tracks near Meudon. The train caught fire, and Jules, his wife, and their two children all died in the flames. This was the first major railway disaster in France, known as the Versailles rail accident.

Jules was buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. This tragedy led to important safety changes, like stopping the practice of locking passengers in their train compartments in France.

Jules Dumont d'Urville was a very important explorer. Many places are named after him, including:

- The D'Urville Sea off Antarctica

- D'Urville Island, Antarctica in Antarctica

- D'Urville Wall on the David Glacier in Antarctica

- Cape d'Urville in Western New Guinea

- Mount D'Urville on Auckland Island

- D'Urville Island in New Zealand

- The Dumont d'Urville Station, a French research base in Antarctica

- A street in Paris, Rue Dumont d'Urville

- A school in Caen, Lycée Dumont D'Urville

Jules himself named Pepin Island and Adélie Land in Antarctica after his wife, Adèle. He also named Croisilles Harbour after his mother's family.

A French naval transport ship and a sloop (a type of ship) have also been named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Jules Dumont D'Urville para niños

In Spanish: Jules Dumont D'Urville para niños