Georges Cuvier facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

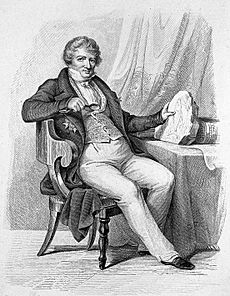

The Baron Cuvier

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier

23 August 1769 |

| Died | 13 May 1832 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Georges Cuvier |

| Known for | Le Règne Animal; establishing the fields of stratigraphy and comparative anatomy, and the principle of faunal succession in the fossil record; making extinction an accepted scientific phenomenon; opposing theories of evolution; popularizing catastrophism |

| Parents |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history, paleontology, anatomy |

| Institutions | Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Collège de France |

| Influences | Conrad Gessner, Buffon, Abraham Gottlob Werner |

| Influenced | Louis Agassiz, Richard Owen |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Cuvier |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Cuvier |

Georges Cuvier (born Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier; August 23, 1769 – May 13, 1832) was a famous French naturalist and zoologist. Many people call him the "founding father of paleontology." He was a very important scientist in the early 1800s.

Cuvier helped create the fields of comparative anatomy and paleontology. He did this by comparing living animals with fossils. His work is seen as the start of vertebrate paleontology, which studies the fossils of animals with backbones. He also improved Linnaean taxonomy, which is a way to classify living things. He added fossils and living species to this system.

Cuvier is also known for proving that extinction is real. At the time, many scientists thought extinction was just a guess. In his book Essay on the Theory of the Earth (1813), Cuvier suggested that species died out because of big, sudden events like floods. This made him a key supporter of catastrophism in geology. He also studied the layers of rock in the Paris basin with Alexandre Brongniart. This work helped create the basic rules of biostratigraphy, which uses fossils to tell the age of rock layers.

Among his many discoveries, Cuvier found that elephant-like bones from North America belonged to an extinct animal he called a mastodon. He also identified a huge skeleton from Argentina as Megatherium, a giant, ancient ground sloth. He named the flying reptile Pterodactylus. He also suggested that reptiles, not mammals, ruled the Earth in prehistoric times.

Cuvier disagreed with early ideas about evolution, especially those from Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Cuvier believed there was no proof for evolution. Instead, he thought life forms were created and then destroyed by global events like floods. His most famous book is Le Règne Animal (The Animal Kingdom), published in 1817. In 1819, he was given the title of Baron for his science work. He died in Paris during a cholera outbreak.

Contents

Georges Cuvier's Life Story

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier was born in Montbéliard. His family had lived there since the Reformation. His mother, Anne Clémence Chatel, taught him very well when he was young. He was always the best student in his class. He learned Latin and Greek easily. He also excelled in math, history, and geography.

When he was 10, Cuvier found a book called Historiae Animalium by Conrad Gessner. This book made him very interested in natural history. He then started reading books by the Comte de Buffon. He remembered so much that by age 12, he knew a lot about animals.

Cuvier spent four more years at the Caroline Academy in Stuttgart. He did very well in all his classes. He learned German quickly and even won a prize for it. His German education introduced him to the work of geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner. Werner's ideas about studying rocks helped shape Cuvier's own scientific methods.

In 1788, Cuvier became a tutor in Normandy. There, he started comparing fossils with living animals. He met Henri Alexandre Tessier, a famous agronomist who was hiding from the Reign of Terror. Tessier introduced Cuvier to other leading naturalists in Paris. In 1795, at age 26, Cuvier moved to Paris. He became an assistant at the Jardin des Plantes, a famous natural history museum. Later, he became a professor of comparative anatomy there.

In 1796, Cuvier gave his first important talk about paleontology. He studied bones from Indian and African elephants, as well as mammoth fossils. He showed that African and Indian elephants were different species. He also proved that mammoths were a separate, extinct species. He identified another fossil, the "Ohio animal," as a new, extinct species. Years later, he named it the "mastodon."

In another paper from 1796, he described a large skeleton found in Paraguay. He named it Megatherium. He realized it was another extinct animal, a giant ground sloth. These two papers were a huge step forward for paleontology and comparative anatomy. They also proved that extinction was a real thing.

Cuvier became a professor at the Collège de France in 1799. He was also a permanent secretary for the Academy of Sciences. He traveled to study public education. He was elected to important scientific groups like the Royal Society and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Cuvier focused on three main areas:

- The structure and classification of mollusks (like snails and clams).

- The anatomy and classification of fish.

- Fossil mammals and reptiles.

Cuvier held many important positions during his life. He was an advisor to Napoleon. He was also president of the Council of Public Instruction. He was a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. He was a Peer of France and a minister under King Louis Philippe. He was a devoted Lutheran and helped found the Parisian Bible society.

Cuvier's Scientific Ideas

Why Cuvier Disagreed with Evolution

Cuvier did not believe in the idea of evolution. He especially disagreed with ideas from Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. These scientists thought that animals slowly changed over time. Cuvier's studies of fossils showed him that animal forms did not gradually change. Instead, they appeared suddenly and then stayed the same until they died out.

Cuvier also studied mummified cats and birds from ancient Egypt. These animals were thousands of years old. He found they were exactly the same as living cats and birds. This supported his idea that life forms did not evolve slowly. He argued that if no change happened in thousands of years, it wouldn't happen over much longer times either.

Cuvier believed that new fossil forms appeared suddenly in the rock record. Then, they stayed the same until they became extinct. He thought this happened because of big disasters, like the flood mentioned in the Bible. Later, some people used Cuvier's ideas to support creationism. However, Cuvier also believed in extinction, which was a new idea at the time.

Cuvier's strong opinions made other scientists hesitant to talk about evolution. This lasted until Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species many years after Cuvier's death.

How Cuvier Proved Extinction

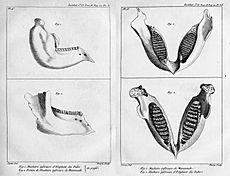

Early in his career, Cuvier published studies of fossil bones. He argued that these bones belonged to large, extinct animals. His first papers identified mammoth and mastodon fossils as extinct species. He also identified the Megatherium as a giant, extinct sloth. He used the structure of their jaws and teeth as key evidence.

Cuvier explained his method: "The form of the tooth leads to the form of the condyle... the thoughtful professor... can reconstruct the entire animal." In simple terms, he believed that every part of an animal's body was connected. By studying one bone, he could figure out what the rest of the animal looked like. He used his huge knowledge of animal anatomy and the museum's collections.

Before Cuvier, many people thought that no animal species had ever died out. They believed that fossils of animals like mammoths were just remains of animals still living in warmer places. Cuvier's studies of elephant fossils from Paris showed they were very different from living elephants. He thought it was silly to believe such huge animals could be hiding somewhere.

His repeated findings of unknown, extinct species, along with rock evidence, led Cuvier to believe that Earth had gone through sudden changes. These changes caused some species to die out.

Other scientists like Darwin and Charles Lyell disagreed with Cuvier's idea of sudden extinction. They thought extinction was a slow process, like the gradual changes on Earth. However, Cuvier's idea of sudden extinction is still true for mass extinction events. These are times when many species die out quickly due to things like volcanoes or asteroids. Cuvier's early work clearly showed that extinction was a real natural process.

Catastrophism: Earth's Big Changes

Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he studied were from species that had died out. In his 1796 paper on elephants, he wrote: All of these facts... seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.

Cuvier thought that humans were not the cause of animal extinction. Instead, he proposed that big natural disasters caused these extinctions. He became a strong supporter of catastrophism. This idea says that many of Earth's features and the history of life can be explained by sudden, catastrophic events. Over time, Cuvier believed there wasn't just one disaster, but several. Each one led to new groups of animals appearing. He wrote about these ideas in his book Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes (Researches on quadruped fossil bones) in 1812.

Cuvier also worked with Alexandre Brongniart to study the rocks around Paris. They used stratigraphy, which is the study of rock layers. They found that these rocks contained fossils of mollusks, mammals, and shells. From this, they concluded that many environmental changes happened quickly. But Earth was often calm for long periods between these sudden events.

After Cuvier's death, catastrophism became less popular. Scientists like Charles Lyell supported uniformitarianism, which says that Earth's features are formed by slow, ongoing forces. However, in recent times, there's been more interest in mass extinctions. This has brought new attention to Cuvier's ideas.

Stratigraphy: Reading Earth's Layers

Cuvier worked with Alexandre Brongniart for several years. They wrote a book about the geology of the Paris region. They published a first version in 1808 and the final one in 1811.

In this book, they identified specific fossils in different rock layers. They used these fossils to understand the layers of sedimentary rock in the Paris basin. They realized that these layers were laid down over a long time. They saw that different animals lived at different times, a concept called faunal succession. They also found that the area was sometimes under seawater and sometimes under fresh water. This work, along with similar studies by William Smith in England, helped create the science of stratigraphy. This was a major step in the history of paleontology and geology.

The Age of Reptiles

In 1800, Cuvier was the first to correctly identify a fossil from Bavaria as a small flying reptile. He named it the Ptero-Dactyle in 1809. This was the first known pterosaur. In 1808, Cuvier identified a fossil from Maastricht as a giant marine lizard, the first known mosasaur.

Cuvier correctly guessed that there was a time when reptiles, not mammals, were the main animals on Earth. This idea was proven true after his death. Many amazing fossil finds, like those by Mary Anning, showed the first ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and dinosaurs.

The Principle of Correlation of Parts

In a paper from 1798, Cuvier explained his "principle of the correlation of parts." He wrote:

- If an animal's teeth are such as they must be, in order for it to nourish itself with flesh, we can be sure... that the whole system of its digestive organs is appropriate for that kind of food...

This means that all the organs in an animal's body are connected and depend on each other. An animal can only survive if all its body parts work together. For example, an animal with teeth for eating meat must also have a digestive system for meat. Its bones and muscles must also be suited for hunting.

How This Idea Was Used

Cuvier believed this principle helped scientists rebuild fossils. Fossils were often found as scattered pieces. By understanding how body parts are connected, scientists could put the bones together correctly. This prevented them from mixing bones from different animals.

This principle also helped Cuvier prove extinction. If a fossil skeleton was correctly rebuilt, he could compare it to living animals. If it was clearly different, it proved the animal was an extinct species.

Cuvier also thought his principle could predict things. For example, when he found a fossil that looked like a marsupial, he correctly guessed it would have certain bones in its pelvis, just like living marsupials.

The Impact of This Principle

Cuvier hoped his ideas would make natural history as scientific as physics or chemistry. He wanted to find laws for anatomy, just like Isaac Newton found laws for physics. He saw his principle as a big step in that direction.

Even though Cuvier sometimes exaggerated the power of his principle, the basic idea is very important in comparative anatomy and paleontology. It helps scientists understand how animals are built and how they lived.

Cuvier's Scientific Work

Comparative Anatomy and Classification

At the Paris Museum, Cuvier studied how animals are classified based on their anatomy. He believed that classification should be based on how organs work together. He called this "functional integration." He put these ideas in his 1817 book, The Animal Kingdom.

Cuvier thought that function was more important than form in classifying animals. He focused on how organs work and how an animal's body works in its environment. He published these ideas in Leçons d'anatomie comparée (Lessons on Comparative Anatomy) and The Animal Kingdom.

Cuvier created four main groups, or "branches," to classify animals. He also divided animals into vertebrates (with backbones) and invertebrates (without backbones). He further divided invertebrates into groups like Mollusca, Radiata, and Articulata. He believed that species could not change from one group to another. This idea was called transmutation. He argued that if an organism changed its physical traits, it would not be able to survive as well. This is why he often disagreed with Lamarck's ideas.

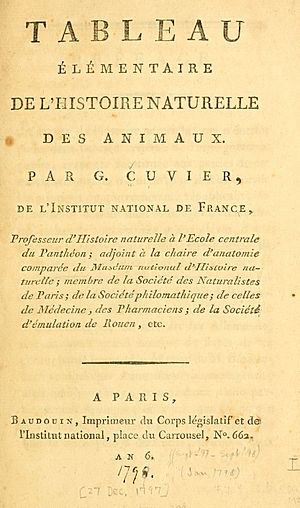

In 1798, Cuvier published his first independent work, Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux. This book was a summary of his lectures and laid the foundation for his classification of the animal kingdom.

Mollusks

Cuvier grouped snails, cockles, and cuttlefish into one category called mollusks. Even though these animals looked different, he noticed a pattern in their overall body structure.

Cuvier started studying mollusks when he first saw the sea in Normandy. His papers on mollusks appeared from 1792 to 1815. They were later collected in a book called Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques in 1817.

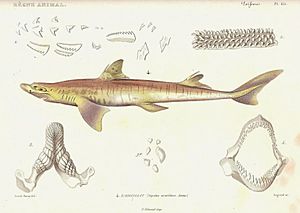

Fish

Cuvier's research on fish began in 1801. It led to the book Histoire naturelle des poissons, which described 5,000 species of fish. He worked on this project with Achille Valenciennes from 1828 to 1831.

Paleontology and Osteology

In paleontology, Cuvier published many papers about the bones of extinct animals. He also studied the skeletons of living animals to understand fossil forms better.

He wrote about the bones of living animals like the Rhinoceros Indicus, the tapir, the hippopotamus, and the sloths.

He did even more work on fossils. He studied extinct mammals from the Eocene beds near Paris. These included fossil species of hippopotamus, Palaeotherium, a marsupial, the Megalonyx, the Megatherium, the cave hyena, the pterodactyl, the cave bear, the mastodon, and extinct species of elephant. If he needed to identify a fossil animal, and the anatomy of living animals was not well known, he would first study the living species in detail. Cuvier essentially created and established the study of fossil Mammals.

Cuvier's main paleontology and geology findings were published in two works: Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes (1812) and Discours sur les revolutions de la surface du globe (1825). In the second book, he explained his scientific theory of Catastrophism.

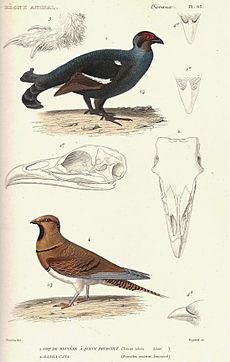

The Animal Kingdom (Le Règne Animal)

Cuvier's most famous work was his Le Règne Animal. It was first published in 1817. A second edition came out in 1829–1830. In this important book, Cuvier shared his lifetime of research on the structure of living and fossil animals. His friend Pierre André Latreille helped him with the section on insects, but Cuvier wrote the rest himself. The book was translated into English many times.

Official and Public Work

Besides his own scientific research, Cuvier did a lot of work as a secretary for the National Institute. He also worked in public education. In 1808, Napoleon appointed him to the council of the Imperial University. He led groups that checked on higher education in areas added to France. He published three reports on this work.

As secretary of the Institute, he wrote many éloges historiques (historical praises) for scientists who had died. He also wrote reports on the history of physical and natural sciences. The most important was Rapport historique sur le progrès des sciences physiques depuis 1789, published in 1810.

After Napoleon's fall, Cuvier kept his important roles. He became chancellor of the university. He also oversaw Protestant theology as a Lutheran. In 1819, he became president of the interior committee, a role he held until his death. In 1826, he received the Legion of Honour. He was later appointed president of the council of state.

How Georges Cuvier is Remembered

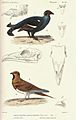

Cuvier is honored by having several animals named after him. These include:

- Cuvier's beaked whale

- Cuvier's gazelle

- Cuvier's toucan

- Cuvier's bichir

- Cuvier's dwarf caiman

- Galeocerdo cuvier (tiger shark)

- Anolis cuvieri (a lizard)

- Oplurus cuvieri (a reptile)

- The fish Hepsetus cuvieri, also known as the African pike.

Some extinct animals are also named after him, like the giant sloth Catonyx cuvieri.

Cuvier Island in New Zealand was named after him by Jules Dumont d'Urville.

Cuvier is mentioned in famous books. In Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue, he is said to have described the orangutan. Arthur Conan Doyle also refers to Cuvier in The Five Orange Pips. In that story, Sherlock Holmes compares his own methods to Cuvier's.

Cuvier's Main Works

- Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux (1797–1798)

- Leçons d'anatomie comparée (5 volumes, 1800–1805)

- Essais sur la géographie minéralogique des environs de Paris, with Alexandre Brongniart (1811)

- Le Règne animal distribué d'après son organisation (4 volumes, 1817)

- Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes (4 volumes, 1812)

- Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques (1817)

- Éloges historiques des membres de l'Académie royale des sciences (3 volumes, 1819–1827)

- Théorie de la terre (1821)

- Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe (1822)

- Histoire des progrès des sciences naturelles depuis 1789 (5 volumes, 1826–1836)

- Histoire naturelle des poissons (11 volumes, 1828–1848), continued by Achille Valenciennes

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Georges Cuvier para niños

In Spanish: Georges Cuvier para niños

- Frédéric Cuvier, Georges Cuvier's younger brother, also a naturalist.

- History of paleontology for more about Cuvier's scientific ideas.

- List of works by James Pradier

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |