July Monarchy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of France

Royaume de France (French)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1830–1848 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Anthem: La Parisienne

("The Parisian") |

|||||||||

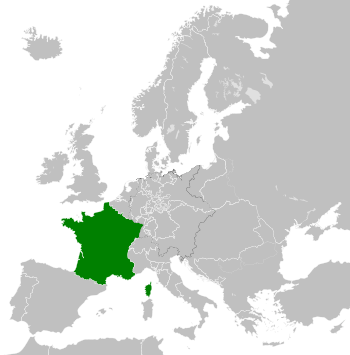

The Kingdom of France in 1839

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||

| Demonym(s) | French | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

|

• 1830–1848

|

Louis Philippe I | ||||||||

|

• 1848

|

Louis Philippe II (disputed) |

||||||||

| President of the Council of Ministers | |||||||||

|

• 1830 (first)

|

Jacques Laffitte | ||||||||

|

• 1848 (last)

|

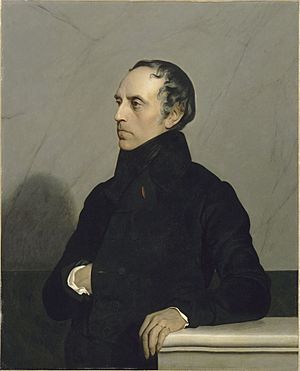

François Guizot | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

| Chamber of Peers | |||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 26 July 1830 | |||||||||

|

• Constitution adopted

|

7 August 1830 | ||||||||

| 23 February 1848 | |||||||||

| Currency | French franc | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | France Algeria |

||||||||

The July Monarchy was a period in France when the country was a constitutional monarchy. This means it had a king, but his power was limited by a constitution and a parliament. It officially began on July 26, 1830, after the July Revolution. This revolution removed the previous king, Charles X, who was from the main House of Bourbon.

The new king was Louis Philippe I. He was from a different, more liberal branch of the Bourbon family, called the House of Orléans. He called himself "King of the French" instead of "King of France." This showed that his power came from the people, not from a divine right. He promised to find a "middle way" between old conservative ideas and new radical ones.

During the July Monarchy, wealthy business people, known as the bourgeoisie, had a lot of power. The government often followed conservative rules, especially when François Guizot was a key minister. King Louis-Philippe also worked to be friends with the United Kingdom and expanded France's colonies, like in Algeria. By 1848, his popularity dropped, and he had to step down. This led to another revolution and the end of the monarchy.

Contents

- Understanding the July Monarchy

- Historical Context: Before the July Monarchy

- Starting the New Government (August – November 1830)

- The Laffitte Government (November 1830 – March 1831)

- The Casimir Périer Government (March 1831 – May 1832)

- Strengthening the Government (1832–1835)

- Moving Towards Parliament (1835–1840)

- The Guizot Government (1840–1848)

- End of the Monarchy

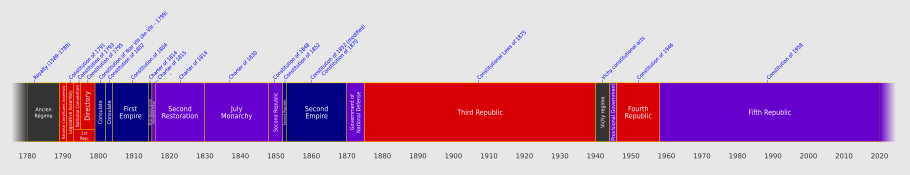

- Timeline of French Constitutions

- See Also

Understanding the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (1830–1848) was a time when the rich middle class, the haute bourgeoisie, had the most influence. It marked a change from the old royal supporters, called Legitimists, to the Orléanists. The Orléanists were more open to the changes that came from the French Revolution of 1789.

King Louis-Philippe was crowned "King of the French." This showed he accepted that the people had power. He tried to be less formal than the previous kings. He surrounded himself with merchants and bankers.

However, this period was not always peaceful. Some people, the Legitimists, wanted the old Bourbon kings back. On the other side, Republicans and Socialists wanted more changes. Later in his rule, King Louis-Philippe became less flexible. He refused to remove his unpopular minister, François Guizot. This led to growing problems and eventually the Revolution of 1848, which ended his rule and started the Second Republic.

In the early years, Louis-Philippe seemed to support reforms. The government's power came from the Charter of 1830. This document promised equal rights for Catholics and Protestants. It also aimed to give more power to citizens through the National Guard and changes to voting rules. However, many of these changes actually helped the government and the wealthy middle class. They didn't truly give more power to all French people.

The number of men allowed to vote roughly doubled during this time. It went from 94,000 under Charles X to over 200,000 by 1848. But this was still only about one percent of the population. Voting was based on how much tax a person paid. This meant that mostly wealthy merchants could vote. This system helped Louis-Philippe's supporters and gave him more control over the French Parliament.

The Charter of 1830 also limited the king's power. It took away his ability to propose laws and limited his executive power. But Louis-Philippe believed the king should be more than just a figurehead. He was very involved in making laws. He appointed Casimir Pierre Perier, a conservative banker, as his first prime minister. Perier worked to shut down Republican groups and labor unions. He also reduced the power of the National Guard when it seemed to support radical ideas.

Perier and François Guizot made the July Monarchy more conservative. They saw radical and republican ideas as a threat. In 1834, the government even made the word "republican" illegal. Guizot closed republican clubs and newspapers. The king also increased the size of the army to ensure its loyalty.

There were always two main groups in the government. One was the liberal conservatives, like Guizot, called the "Party of Resistance." The other was the liberal reformers, like the journalist Adolphe Thiers, called the "Party of Movement." The reformers never gained full control. Guizot's time in power was known for cracking down on dissent. He also supported policies that helped businesses, like protective taxes. These policies benefited the wealthy supporters of the government. Workers had no right to form unions or ask for better pay. Guizot famously told those who couldn't vote to "enrich yourselves" (enrichissez-vous).

Louis-Philippe was brought to power by an alliance of ordinary Parisians, Republicans, and the liberal middle class. But by the end of his rule, he was overthrown by similar citizen uprisings in 1848. This led to the creation of the Second Republic.

After Louis-Philippe was removed and went into exile, some people still wanted the Orléans family back on the throne. But the July Monarchy was the last time a Bourbon or Orléans king ruled France.

Historical Context: Before the July Monarchy

After Napoléon Bonaparte was removed in 1814, the old Bourbon royal family was put back on the French throne. This period was called the Bourbon Restoration. It was a time of conservative rule, and the Catholic Church regained power. Louis XVIII ruled from 1814 to 1824. His brother, Charles X, took over in 1824. Charles X was even more conservative.

Even with the Bourbons back, France had changed a lot since the Revolution. Ideas of equality and freedom were still strong. Economic changes had also shifted power from noble landowners to city merchants. Napoleon's reforms, like the Napoleonic Code, also remained. These changes created a strong central government, very different from the old system.

Louis XVIII generally accepted these changes. But he faced pressure from extreme royalists who wanted to go back to the old ways. His brother, Charles X, was much more conservative. He tried to give back to the aristocrats what they had lost in the revolution. He also limited freedom of the press and increased the Church's power.

In 1830, people were unhappy with Charles X's strict rule. His choice of a very conservative minister, Prince de Polignac, led to an uprising in Paris. This event was the 1830 July Revolution. Charles X was forced to leave. Louis-Philippe, from the Orléans family, became king. He ruled as "King of the French," showing a new relationship between the ruler and the people.

Starting the New Government (August – November 1830)

New Symbols and Ideas

On August 7, 1830, the old constitution was updated. The part that linked the king to the old system was removed. The "King of France" became the "King of the French." This meant the king's power came from the nation, not from God. Laws supporting Catholicism and limiting free speech were removed. The revolutionary tricolor flag was brought back.

Louis-Philippe took an oath to this new constitution on August 9. This was the start of the July Monarchy. Two days later, the first government was formed. It included people who had opposed Charles X, like Casimir Perier and Jacques Laffitte. Their main goal was to bring back order while still respecting the revolutionary spirit that brought them to power.

Louis-Philippe chose the symbols of his family, the House of Orléans, as the new state symbols. He was very happy when the Parisian National Guard cheered for this change. The government also decided to help people who were hurt during the revolution. They gave money to orphans, widows, and injured people. They also created a special medal for the July Revolutionaries.

Ministers no longer used fancy titles like "Monseigneur." They were simply called "Monsieur le ministre." The king's oldest son, Ferdinand-Philippe, became the "Prince Royal." His sisters were called "princesses of Orléans," not "of France." This showed that the old idea of a "King of France" was gone.

Unpopular laws from the previous period were removed. This included a law that had banished people who voted for the death of Louis XVI. The Church of Sainte-Geneviève became a secular building again, called the Panthéon. The government also reduced funding for the Catholic Church.

Ongoing Problems

Public unrest continued for three months. The government struggled to stop it. This was partly because the National Guard was led by Lafayette, a Republican leader. Republicans formed clubs, like during the 1789 Revolution. Some of these were secret groups that wanted political and social changes. Strikes and protests happened all the time.

To help the economy and restore order, the government spent money on public works, like roads. They also helped struggling businesses with loans. These funds mostly went to large businesses that supported the new government.

The death of the Prince of Condé in August 1830 caused a scandal. Some people accused Louis-Philippe of being involved. They claimed he wanted his son to inherit the Prince's wealth.

Removing Old Supporters

The government removed all officials who supported the old Legitimist regime. Many people who had worked for Napoleon's First Empire, and had been removed earlier, now returned to government jobs. The Minister of the Interior, Guizot, replaced many local officials. The Minister of Justice also removed many public prosecutors. In the army, generals loyal to Charles X were replaced.

In the Parliament, a quarter of the seats were re-elected in October. This led to the defeat of the Legitimists. However, these changes didn't bring entirely new people into power. Landowners, civil servants, and professionals still held most positions.

Two Political Groups: Resistance and Movement

Two main political groups emerged during this time: the "Party of Movement" and the "Party of Resistance." The Movement Party wanted reforms and supported nationalist movements across Europe. Their newspaper was Le National. The Resistance Party was conservative. They wanted peace with other European kings. Their newspaper was Le Journal des débats.

A major issue was the trial of Charles X's former ministers. People on the left wanted them punished severely. But Louis-Philippe feared this would lead to more violence. The Parliament decided to charge the ministers. They also asked the king to propose a law to end the death penalty for political crimes. This made some people angry, and protests happened in October.

After these riots, Interior Minister Guizot asked the Paris official, Odilon Barrot, to resign. Barrot had criticized the Parliament. This led to other ministers resigning. Jacques Laffitte, a leader of the Movement Party, then became the new prime minister in November 1830.

The Laffitte Government (November 1830 – March 1831)

Louis-Philippe didn't fully trust Laffitte. He secretly promised not to support him. But Laffitte believed the king would back him.

The trial of Charles X's former ministers happened in December 1830. Rioters demanded their death. But the ministers were sentenced to life in prison. The National Guard helped keep order in Paris. This showed the Guard was a key protector of the new government.

Because the National Guard became so important, Lafayette had to resign. This also led to the Justice Minister's resignation. To avoid relying only on the National Guard, the king asked Marshal Soult, the new Minister of War, to reorganize the army. In February 1831, Soult proposed reforms, including the creation of the Foreign Legion.

The government also passed reforms requested by the Movement Party. A law in March 1831 allowed local councils to be elected. This greatly increased the number of people who could vote in local elections. Another law in April 1831 lowered the income needed to vote in national elections. This increased the number of national voters from under 100,000 to 166,000. Still, only about one in 170 Frenchmen could vote.

February 1831 Riots

Despite these reforms, Paris saw more riots in February 1831. These riots led to Laffitte's government falling. The riots started after a funeral service for the Duke of Berry, who had been killed in 1820. This event turned into a political protest for the old royal family. Rioters attacked churches for two days. The unrest spread to other cities.

The government did not strongly suppress the riots. Officials like the Paris prefect and police chief remained passive. This angered Guizot. The government even arrested the Archbishop of Paris and other priests, accusing them of causing the protests.

To calm things down, Laffitte suggested removing the fleur-de-lys, a symbol of the old monarchy, from state symbols. Louis-Philippe reluctantly agreed. This new defeat for the king sealed Laffitte's fate.

On February 19, 1831, Guizot criticized Laffitte in Parliament. Laffitte offered to resign, but the king waited. Meanwhile, some officials were replaced. The economy was also in a bad state.

Louis-Philippe finally tricked Laffitte into resigning. He had his Foreign Affairs Minister show Laffitte a note about Austria possibly intervening in Italy. Laffitte, feeling betrayed, resigned. Most of his ministers had already planned to join the next government.

The Casimir Périer Government (March 1831 – May 1832)

The king then brought the "Party of Resistance" to power. He wasn't very fond of their leader, Casimir Pierre Périer, a banker. Périer became prime minister on March 13, 1831. The king wanted Périer to restore order and take responsibility for unpopular decisions.

Périer set conditions for the king. He insisted that the prime minister would be more important than other ministers. He also said the king's son, the Prince Royal, would no longer attend cabinet meetings. Périer also wanted to boost the king's image. He asked Louis-Philippe to move from his family home to the royal palace.

Périer announced his government's principles on March 18, 1831. He said the July Revolution was about resisting aggression, not starting uprisings. He also promised a peaceful foreign policy. Parliament largely supported his government. Périer made sure his cabinet worked together and disciplined those who disagreed. He stopped the government from getting involved in labor disputes, favoring employers instead.

Worker Protests and Government Response

In March 1831, a group started a national organization to fight against any return of the old Bourbon kings. Many Republican leaders supported it. Périer's government banned civil servants from joining this group, saying it challenged the state.

In April 1831, the government took unpopular actions. Several important people were dismissed. When a court acquitted some young Republicans arrested during the December 1830 troubles, new riots broke out. But Périer used the military and National Guard to break up the crowds. In May, the government used water hoses for crowd control for the first time.

Another riot in Paris in June 1831 turned into a battle with the National Guard and army. The biggest unrest happened in Lyon with the Canuts Revolt in November 1831. The Canuts, who were silk workers, took control of the city. Périer sent 20,000 soldiers to Lyon, who restored order peacefully.

Civil unrest continued in other cities too. In March 1832, a protest in Grenoble turned violent. The government dissolved the National Guard there and brought back the army. Republican plots also threatened the government. The police, organized during the French First Empire, were everywhere. The strength of the opposition made the Prince Royal lean more to the right.

Elections of 1831

In May 1831, Louis-Philippe visited Normandy and Picardy, where he was well received. He also traveled to the east, where there were more Republican and Bonapartist activities. He firmly rejected calls for changes like abolishing noble titles or intervening in Poland.

On May 31, 1831, Louis-Philippe dissolved the Parliament and called for new elections. The elections took place in July. The results were not what the king wanted. More than half of the previous members were re-elected. The Legitimists got 104 seats, the Orléanist Liberals 282, and the Republicans 73.

On July 23, 1831, the king outlined Périer's program: strict enforcement of the constitution at home and protecting France's interests abroad. The Parliament elected a government supporter as its president. But a Republican leader became the first vice president. Périer felt his majority was not strong enough and decided to resign.

However, when William I of the Netherlands invaded Belgium in August 1831, Périer had to stay in power to help Belgium. During debates about intervening in Belgium, some members asked for France to help Poland. Périer also agreed to abolish hereditary noble titles, a demand from the Left. A law in March 1832 set the king's annual allowance at 12 million francs. Another law in April 1832 reformed the criminal code.

The 1832 Cholera Epidemic

A cholera outbreak reached Paris around March 1832. It killed over 13,000 people in April alone. The disease caused panic. People suspected poisoners, and beggars protested against public health measures.

The cholera also affected the royal family and ministers. Casimir Périer visited patients and caught the disease. He died on May 16, 1832.

Strengthening the Government (1832–1835)

King Louis-Philippe was not sad about Périer's death. He felt Périer took all the credit for successes. The king was in no hurry to find a new prime minister.

The government faced attacks from all sides. The Legitimist Duchess of Berry tried to start an uprising in southern France. Republicans led an uprising in Paris in June 1832 during a funeral. General Georges Mouton crushed this rebellion. This double victory helped strengthen the July Monarchy. Also, the death of Napoleon's son in July 1832 weakened the Bonapartist opposition.

Louis-Philippe's daughter married the King of the Belgians in August. This royal marriage strengthened France's position abroad.

First Soult Government

Louis-Philippe appointed Marshal Soult as prime minister in October 1832. Soult was supported by a group of powerful politicians: Adolphe Thiers, the duc de Broglie, and François Guizot. Soult promised to continue Périer's policies: "order at home" and "peace abroad." He also spoke against both Legitimist and Republican opposition.

The new Interior Minister, Adolphe Thiers, had a success in November 1832. He arrested the rebellious Duchess of Berry. She was later sent to Palermo.

The new parliamentary session in November 1832 was a success for the government. Their candidate was easily elected as President of the Chamber. In Belgium, Marshal Gérard helped the new Belgian monarchy by taking back a key fortress.

Louis-Philippe then visited different parts of France. He met the victorious Marshal Gérard and his soldiers. He also visited Normandy, where Legitimist troubles continued. To gain public support, the government took popular actions. They started public works, like finishing the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. They also put Napoleon's statue back on the Colonne Vendôme. The Minister of Public Instruction, François Guizot, passed a law in June 1833. This law created an elementary school in every town.

A change in ministers happened after the Duke de Broglie resigned in April 1834. He disagreed with Parliament over a treaty with the United States. This was good for the king, as he didn't like Broglie.

April 1834 Uprisings

New laws restricting public criers and associations led to violent unrest in France in February and April 1834. On April 9, the Second Canut Revolt exploded in Lyon. Interior Minister Adolphe Thiers allowed the city to be taken by insurgents, then retook it on April 13.

Republicans tried to spread the uprising to other cities, but failed. The biggest danger was in Paris. Thiers had 40,000 soldiers there. He also arrested 150 Republican leaders and banned their newspaper. Despite this, barricades were set up on April 13. This led to harsh repression, including a massacre in one house.

To show support for the monarchy, both parts of Parliament met. Louis-Philippe canceled his birthday celebration and gave the money to orphans and the injured. He also ordered Marshal Soult to tell people about these events to gain support for increasing the army.

Over 2,000 people were arrested after the riots. Their cases went to the Chamber of Peers. The Republican movement was severely weakened. Parliament also voted to increase the army to 360,000 men and passed a strict law on military weapons.

1834 Elections

Louis-Philippe decided to dissolve Parliament and hold new elections in June 1834. The results were not as good as he hoped. Republicans were almost gone, but the Opposition still had about 150 seats. A new group, the Tiers-Parti, could sometimes vote against the government. The new Parliament re-elected a government supporter as its president. But they also voted for an address to the king that criticized him. The king then suspended Parliament until the end of the year.

Short-Lived Governments (July 1834 – February 1835)

Thiers and Guizot, who were very powerful, decided to remove Marshal Soult. They used an issue about French land in Algeria to make him resign in July 1834. Marshal Gérard replaced him. But Gérard also resigned in October 1834 over the issue of amnesty for the 2,000 prisoners from April. Louis-Philippe and the conservatives opposed the amnesty.

Gérard's resignation led to a four-month government crisis. Louis-Philippe tried to form a government from the Tiers-Parti. But after several failed attempts, he appointed a figure from the First Empire, the duc de Bassano, as prime minister. Bassano was in debt, and his creditors tried to seize his salary. All his ministers resigned three days later. This government became known as the "Three Days Ministry." Louis-Philippe then appointed Marshal Mortier as prime minister.

Mortier's government won a vote of confidence in December 1834. But Mortier resigned two months later, in February 1835, due to health reasons. The opposition said his government had no real leader and that Mortier was just Louis-Philippe's puppet. The phrase "the king reigns but does not rule" was now used against Louis-Philippe.

Moving Towards Parliament (1835–1840)

The debates about Mortier's resignation focused on the power of Parliament. Louis-Philippe wanted to control his own policies, especially in military and foreign affairs. He also wanted to lead the government directly, sometimes bypassing the prime minister. But many members of Parliament believed ministers should be led by someone who had the support of the majority in Parliament. The constitution did not clearly define the role of the prime minister.

The Broglie Ministry (March 1835 – February 1836)

Parliament decided to support Victor de Broglie as prime minister. This was mainly because Louis-Philippe disliked him. After a three-week crisis, the king had to accept Broglie and his conditions.

The new government was led by Broglie (Foreign Affairs), Guizot (Public Instruction), and Thiers (Interior). Broglie's first act was to get Parliament to approve a treaty with the United States that they had rejected before. He also won a vote on secret funds, which showed he had strong support.

Trial of the April Insurgents

Broglie's most important task was the trial of the April insurgents. It began in May 1835. Out of 2,000 prisoners, only 164 were convicted. Many of them escaped through a tunnel. The sentences were mild: some were deported, many got short prison terms, and some were acquitted.

The Fieschi Attack (July 1835)

The trial of the insurgents made Republicans seem radical. This worried the public. The Fieschi attack in July 1835 further scared people. It happened during a National Guard review by Louis-Philippe.

A special gun with 25 barrels was fired at the king from a window. The king was only slightly hurt. His sons were unharmed. But Marshal Mortier and ten other people were killed. Many others were injured.

The attackers, Giuseppe Fieschi and two Republicans, were arrested. They were sentenced to death and executed in February 1836.

The September Laws

The Fieschi attack shocked France. Public opinion was ready for strong measures against Republicans.

Three new laws were passed in August 1835. The first strengthened the powers of judges and prosecutors against rebels. The second changed jury rules, making it easier to get a guilty verdict. The third law limited freedom of the press. It aimed to stop discussions about the king, the royal family, and the monarchy. This law caused heated debates but was approved.

Strengthening the Government

These three laws were put into effect on September 9, 1835. They showed the success of the "Resistance" policy against Republicans. The July Monarchy was now more secure. Discussions about its right to rule were outlawed. The opposition could only debate how to interpret the constitution and push for more parliamentary power. Calls for more people to vote became more common.

The Broglie government eventually fell over a financial issue. The Finance Minister wanted to reduce interest on government bonds. This was unpopular with the wealthy supporters of the government. The Parliament voted against the government's stance. This was the first time a government fell because Parliament voted against it. This was a victory for the idea of parliamentary government.

The First Thiers Government (February – September 1836)

Louis-Philippe then decided to try a parliamentary approach. He wanted to get rid of the conservative ministers like Broglie and Guizot. He appointed Adolphe Thiers as prime minister in February 1836. The king hoped Thiers would distance himself from the liberals. He also wanted Thiers to use up his popularity in government.

Thiers' main goal was to arrange the Duke of Orléans' marriage to an Austrian archduchess. The king was very keen on this marriage after the Fieschi attack. Thiers wanted to make a big change in European alliances. But Austria's leaders didn't want an alliance with the Orléans family, as they thought France was too unstable.

Another assassination attempt on Louis-Philippe in June 1836 confirmed Austria's fears. These setbacks upset Thiers. The inauguration of the Arc de Triomphe in July 1836, meant to be a grand national event, happened quietly without the king present.

To regain popularity and get back at Austria, Thiers considered military action in Spain. But Louis-Philippe strongly opposed this. This disagreement led to Thiers' resignation. This showed that the government could still fall due to disagreements with the king, not just Parliament.

The Two Molé Governments (September 1836 – March 1839)

Count Molé formed a new government in September 1836. It included conservative ministers like Guizot. Molé immediately took some popular actions. He improved prisons, ended public chain gangs, and pardoned 52 political prisoners. In October 1836, the inauguration of the Luxor Obelisk in Paris was a public success for the king.

1836 Bonapartist Uprising

In October 1836, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte tried to start an uprising in Strasbourg. It was quickly stopped, and he was arrested. The king wanted to avoid a public trial. He sent Louis-Napoléon to the United States without legal proceedings. The other plotters were acquitted in January 1837.

New Laws and Challenges

In January 1837, the War Minister proposed a law to separate trials for civilians and non-civilians during insurrections. The opposition rejected it. Louis-Philippe decided to keep the Molé government, even though it lacked strong parliamentary support. The new government was seen as the "Cabinet of the castle" and expected to fail.

The Duke of Orléans' Wedding

However, Molé surprised his critics by announcing the upcoming wedding of the Prince Royal, Ferdinand Philippe, to the Duchess Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Parliament then approved increased allowances for the Duke of Orléans and the Queen of the Belgians.

Molé's government gained Parliament's confidence. In May 1837, a general amnesty was granted to all political prisoners. Crosses were put back in courts, and a church closed since 1831 was reopened. To show that order was restored, the king reviewed the National Guard. The Duke of Orléans' wedding was celebrated in May 1837.

A few days later, in June, Louis-Philippe opened the Château de Versailles. Its restoration, which he personally funded, was meant to create a Museum of the History of France. It would display the military glories of the Revolution, the Empire, and the old monarchy side by side, symbolizing national unity.

1837 Elections

Molé's government seemed stable, helped by a good economy. The king and Molé decided to dissolve Parliament again in October 1837. To influence the elections, Louis-Philippe ordered a military expedition in Algeria. This was a success.

However, the November 1837 elections did not meet the king's hopes. Only a little over half of the members supported the government. There were also Legitimists, Republicans, and other opposition groups. This meant the Parliament was divided.

Molé's government faced pressure, especially from Adolphe Thiers. But with help from conservatives, Molé got a favorable vote for the address to the king in January 1838. Molé's cabinet seemed to be controlled by the conservatives, just as Guizot was distancing himself from Molé.

In May 1838, Parliament rejected the government's railway plan. In December 1838, a government supporter was elected President of the Chamber by a very small margin. A group of opposition leaders had formed a coalition. But Parliament still voted for a generally favorable address to the king.

1839 Elections

Facing a weak majority, Molé resigned in January 1839. Louis-Philippe tried to refuse his resignation, then asked Marshal Soult to form a government. Soult agreed, on the condition of holding new elections. The opposition criticized this, comparing it to Charles X's actions in 1830. Thiers even compared Molé to one of Charles X's unpopular ministers.

The March 1839 elections were a disappointment for the king. The opposition coalition gained more seats. Molé resigned again in March, and Louis-Philippe had to accept it.

Second Soult Government (May 1839 – February 1840)

After Molé's fall, Louis-Philippe asked Marshal Soult again. Soult tried to form a government with the three main opposition leaders, but they refused. This forced the king to delay the opening of Parliament. Thiers also refused to work with some other leaders. Finally, Louis-Philippe formed a temporary, neutral government in March 1839.

Parliament opened in April in a tense atmosphere. A large crowd gathered, singing and rioting. The left-wing press accused the government of causing trouble. Thiers supported Odilon Barrot for President of the Chamber. But some of Thiers' friends were disappointed with him. Another candidate won, showing that the opposition coalition had broken apart.

The government still struggled to form a new cabinet. Then, on May 12, 1839, a secret Republican group organized an uprising in Paris. It failed, and the plotters were arrested. This allowed Louis-Philippe to form a new government on the same day, led by Marshal Soult.

The new government easily passed its budget. Parliament went on break in August. When it reopened in December, it voted for a favorable address to the government. However, Soult's government fell in February 1840. This happened when Parliament voted against a proposed allowance for the Duke of Nemours, who was about to get married.

The Second Thiers Cabinet (March – October 1840)

Soult's fall forced the king to appoint Adolphe Thiers, a key figure from the left. Thiers wanted to firmly establish parliamentary government. He believed the king should "reign but not rule." He formed his government in March 1840.

Relations with the king were difficult from the start. Louis-Philippe tried to embarrass Thiers by suggesting he promote a friend, which would expose Thiers to criticism. Thiers delayed the promotion.

Thiers' government was generally conservative, protecting the interests of the wealthy. He supported a proposal to convert government bonds, which was a left-wing idea. But he knew Parliament's upper house would reject it, which they did. In May 1840, Thiers strongly rejected universal suffrage and social reforms. He argued against linking voting reform with social changes.

Thiers also supported the wealthy by renewing the Banque de France's special privileges. He also approved government money for steamship lines and railway companies.

Return of Napoleon's Ashes

While Thiers favored the wealthy, he also tried to appeal to the public's desire for glory. In May 1840, the Interior Minister announced that the king had decided to bring Napoleon's remains back to France. They would be placed in the Invalides. The British government agreed to this.

This announcement created a wave of patriotism. Thiers saw it as a way to honor the Revolution and the Empire. Louis-Philippe, though hesitant, wanted to gain some of Napoleon's glory for himself. Prince Louis-Napoléon tried to use this opportunity to start an uprising in August 1840. But his attempt failed, and he was arrested.

His trial happened in September and October 1840. Most people were more interested in another trial happening at the same time. Louis-Napoléon was sentenced to life in prison.

Colonization of Algeria

The conquest of Algeria, which started earlier, faced resistance from Abd-el-Kader. Thiers pushed for colonizing more of the country. He convinced the king, who saw Algeria as a place for his son to gain military fame. General Bugeaud, known for his harsh methods, was appointed governor general in December 1840.

Middle East Affairs and Thiers' Fall

Thiers supported Muhammad Ali Pasha, the ruler of Egypt. Muhammad Ali wanted to create a large Arab Empire. Thiers tried to help him make a deal with the Ottoman Empire without involving other European powers. However, the British Foreign Minister, Lord Palmerston, found out. He quickly negotiated a treaty with Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia to solve the "Eastern Question."

When the London Convention was revealed in July 1840, it caused a patriotic uproar in France. France felt left out of an area where it had influence. Thiers tried to appeal to patriotic feelings by mobilizing part of the army and starting work on Paris's fortifications. But France remained passive when the British navy acted in Lebanon. Muhammad Ali was then removed as ruler by the Ottoman Sultan.

After long talks, a compromise was reached in October 1840. France would not support Muhammad Ali's claims in Syria, but insisted Egypt remain independent. Britain then recognized Muhammad Ali's rule in Egypt. This brought things back to how they were in 1832. But the break between Thiers and Louis-Philippe was final. Thiers and his ministers resigned in October 1840. Louis-Philippe then called Marshal Soult and Guizot back to Paris.

The Guizot Government (1840–1848)

When Louis-Philippe brought Guizot and his conservative group to power, he probably thought it would be temporary. But Guizot's government stayed together and gained the king's trust. Guizot became his favorite prime minister.

Guizot arrived in Paris in October 1840. He took the role of Foreign Affairs Minister and let Soult be the official prime minister. This pleased the king. Guizot was confident he could control the old Marshal Soult. Since the center-left had refused to join, Guizot's government was made up only of conservatives.

The July Column was built to honor the 1830 Revolution. The Middle East issue was settled by a treaty in 1841. This helped France and Britain become friends again. It also increased public support for colonizing Algeria.

Both the government and Parliament were supporters of the Orléans monarchy. They were divided into different groups. Odilon Barrot's group wanted more people to vote. Thiers' group wanted to limit the king's power. The conservatives, led by Guizot and Molé, wanted to keep the system as it was.

Guizot refused any reforms, including allowing more people to vote. He believed the monarchy should favor the "middle classes." These were people who owned land, worked hard, and saved money. His famous saying was: "Get rich through work and savings and then you will be electors!" (« Enrichissez-vous par le travail et par l'épargne et ainsi vous serez électeur ! »). Guizot was helped by a good economy, with growth of about 3.5% per year from 1840 to 1846. The transport network grew quickly. A law in 1842 organized the national railway network, which expanded greatly. This showed that the Industrial Revolution had fully arrived in France.

A System Under Threat

This period of industrial growth also brought a new problem: pauperism. This meant many people were very poor, especially workers. They had long working days, low pay, and no right to form unions. Many people were beggars or relied on charity. The only social law passed during the July Monarchy was in 1841. It banned child labor for children under eight and night work for those under 13. But this law was rarely enforced.

Some Christians proposed a "charitable economy." Ideas of Utopian Socialism also spread. Other thinkers discussed socialist revolutions or mutualism. Meanwhile, Liberals believed in a free market and ending tariffs.

Final Years (1846–1848)

The harvest in 1846 was bad in France and other parts of Europe. This caused wheat prices to rise, leading to a food shortage. People had less money to buy other things. This led to a crisis of too many goods being produced. Factories laid off many workers, and people withdrew their savings, causing a banking crisis. Many businesses went bankrupt, and stock prices fell. The government imported wheat, which hurt the country's trade balance. Public works projects stopped.

In Britain, the government changed, bringing in ministers who were seen as a threat to France. Guizot's efforts to be friends with Britain were undone by a dispute over Spanish royal marriages.

Workers' protests increased. There were riots in 1847. In the industrial city of Roubaix, 60% of workers were unemployed.

Since the right to form groups was limited and public meetings were banned after 1835, the opposition was restricted. To get around this, people used funerals and banquets as excuses for public gatherings. Towards the end of the monarchy, a series of banquets took place in major cities. Louis-Philippe reacted strongly and banned the final banquet in January 1848. This ban led to the February 1848 Revolution.

End of the Monarchy

After some unrest, the king replaced Guizot with Thiers, who supported using force. But the king was met with hostility from his own troops. He decided to step down in favor of his grandson, Philippe d'Orléans. He made his daughter-in-law, Hélène de Mecklembourg-Schwerin, regent. But his actions were too late. The Second Republic was declared on February 26, 1848.

Louis-Philippe, who called himself the "Citizen King," believed his power came from the people. But he didn't realize that the French people wanted more people to be able to vote.

Even though the end of the July Monarchy brought France close to civil war, it was also a time of great artistic and intellectual creativity.

Timeline of French Constitutions

See Also

- France during the nineteenth century

- Liberalism and radicalism in France

- French art of the 19th century

- French literature of the 19th century

- History of science

- Politics of France

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |