France in the long nineteenth century facts for kids

In the history of France, the period from 1789 to 1914 is often called the "long 19th century." This time stretches from the start of the French Revolution all the way to World War I. It includes many different governments and big changes:

- French Revolution (1789–1792)

- French First Republic (1792–1804)

- First French Empire (1804–1814/1815)

- Bourbon Restoration (1814/1815–1830)

- July Monarchy (1830–1848)

- Second Republic (1848–1852)

- Second Empire (1852–1870)

- French Third Republic (1870–1940)

- Belle Époque (1871–1914)

Contents

- France's Changing Landscape and People

- The French Revolution (1789–1792)

- The First Republic (1792–1799)

- The First Empire (1804–1814)

- The Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830)

- The July Monarchy (1830–1848)

- The Second Republic (1848–1852)

- The Second Empire (1852–1870)

- The Third Republic (from 1870)

- Images for kids

France's Changing Landscape and People

How France's Borders Changed

When the French Revolution began, France was already close to its modern size. During the 19th century, it added areas like Savoy and Nice, and some smaller places.

France's borders grew a lot during the time of the Revolution and Napoleon's wars. But after Napoleon's defeat, these extra lands were given back. Savoy and Nice were finally added to France in 1860 after a war.

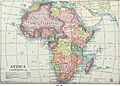

In 1830, France took over Algeria in North Africa. By 1848, Algeria became a full part of France. Later in the 1800s, France started building a huge overseas empire. This included places like French Indochina (today's Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos) and large parts of Africa. This led to competition with Britain.

After losing the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, France lost the regions of Alsace and parts of Lorraine to Germany. These areas were only returned to France after World War I.

How Many People Lived in France?

From 1795 to 1866, France was the second most populated country in Europe, after Russia. Globally, it was the fourth most populated. But unlike other European countries, France's population didn't grow much from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s. In 1789, about 28 million people lived in France. By 1850, it was 36 million, and by 1880, about 39 million. This slow growth was a big concern, especially as Germany's population and industry grew much faster.

Until 1850, most people lived in the countryside. But slowly, more people started moving to cities, especially during the Second Empire. France's industrial growth happened later than in England. In the 1830s, France had a small iron industry and not much coal. Most people were farmers.

New schools for engineers and better primary education helped prepare for industrial growth in later years. French railways started slowly in the 1830s and really grew in the 1840s. By 1848, more industrial workers were involved in politics. By 1914, the number of industrial workers grew from 23% to 39%. Still, France remained a mostly rural country, with 40% of people still farming in 1914.

In the 19th century, many people moved to France from Eastern Europe (like Germany, Poland, Russia) and from Mediterranean countries (like Italy and Spain). Many Belgian workers came to work in French factories, especially in textiles.

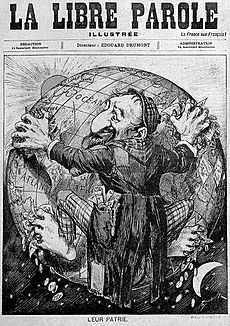

France was the first European country to give full rights to its Jewish population during the French Revolution. The Crémieux Decree of 1870 gave full citizenship to Jews in French Algeria. By 1872, about 86,000 Jews lived in France. Many tried to fit into French society, though the Dreyfus affair later showed that some French people were still against Jews.

Language and National Identity

At the start of the 19th century, France was a mix of different languages. People in the countryside spoke many regional languages. France only became a country with one main language by the end of the 1800s. This was largely thanks to education policies by Jules Ferry during the Third Republic. In 1870, about 33% of peasants couldn't read. By 1914, almost all French people could read and understand the national language.

Through education, social changes, and military service, the Third Republic helped turn France from a "country of peasants into a nation of Frenchmen." By 1914, most French people could read French, and fewer spoke regional languages. The power of the Catholic Church in public life also greatly decreased. People were actively taught a strong sense of national identity and pride.

France's Economy: A Slow Start

France's economy in the 19th century was shaped by the Napoleonic era, competition with Britain, and major wars. France's economic growth per person was a bit slower than Britain's. Also, Britain's population grew much faster, so its overall economy grew more quickly.

Historians describe France's economic growth in cycles:

- 1815–1840: Growth was uneven.

- 1840–1860: Fast growth.

- 1860–1882: Slowing down.

- 1882–1896: Stagnation (no growth).

- 1896–1913: Fast growth again.

Compared to other advanced countries between 1870 and 1913, France's growth per person was about average. But because its population grew so slowly, France's total economic growth was one of the lowest. French factories were often smaller and used older machines than those in other countries. Many people still worked from home or in small workshops. France didn't catch up to Britain and was even overtaken by countries like Belgium, Germany, and the United States.

The French Revolution (1789–1792)

The End of the Old System (to 1789)

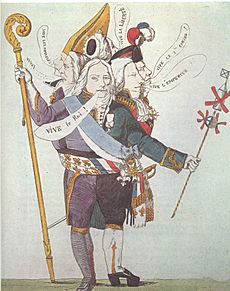

King Louis XVI (1774–1792) faced big money problems because of expensive wars. People were also unhappy with the special rights given to nobles and church leaders. These problems led to a meeting called the Estates-General in 1789.

On May 28, 1789, the Third Estate (common people) decided to act on their own. They declared themselves the National Assembly, meaning they represented "the People." When the king locked their meeting hall, they moved to a tennis court. There, they took the Tennis Court Oath on June 20, 1789, promising not to stop until France had a new constitution. Many clergy and nobles soon joined them.

On July 11, 1789, King Louis XVI fired his reform-minded minister, Necker. Many in Paris thought this was the start of a royal attack and began to rebel. On July 14, 1789, rebels attacked and seized the Bastille fortress, a symbol of royal power. The king and his supporters backed down.

After this violence, many nobles, called émigrés, fled France. Some of them started planning a civil war and tried to get other European countries to fight France. The idea of people having power spread across France. In the countryside, farmers burned records of their debts and even some castles, in what was called "la Grande Peur" (the Great Fear).

A King with Limited Power (1789–1792)

On August 4, 1789, the National Assembly ended feudalism. This meant nobles lost their special rights, and the Church could no longer collect a tax on crops. The Church's land, which was a lot, was taken by the state. New laws also ended monastic vows (promises made by monks and nuns). The Civil Constitution of the Clergy (July 12, 1790) made church leaders state employees and required them to swear loyalty to the constitution.

Inspired by the American Declaration of Independence, the Assembly published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen on August 26, 1789. This document stated important principles about human rights. The Assembly also divided France into 83 départements, which were easier to manage. They also removed old symbols of the monarchy, which made more conservative nobles unhappy and led more of them to leave France.

King Louis XVI didn't like the direction of the revolution. On June 20, 1791, the royal family tried to escape from Paris. But the king was recognized and brought back under guard. Most of the Assembly still wanted a king with limited power, not a republic. They reached a compromise where Louis XVI remained king but had very little real power. He had to swear an oath to the new constitution.

Meanwhile, other European countries became worried. The Holy Roman Emperor and the King of Prussia, along with the king's brother, issued the Declaration of Pillnitz. This statement said they supported Louis XVI and threatened to invade France if the revolutionaries didn't free him and dissolve the Assembly. This led France to declare war on Austria on April 20, 1792. Prussia joined Austria a few weeks later, starting the French Revolutionary Wars.

The First Republic (1792–1799)

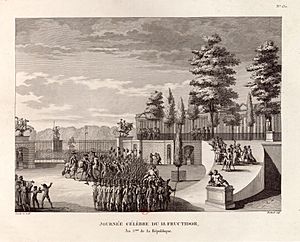

In the Brunswick Manifesto, the armies of Austria and Prussia threatened to harm the French people if they resisted the return of the monarchy. This made King Louis seem like he was working with France's enemies. He was arrested on August 10, 1792. On September 20, French revolutionary troops won their first big victory at the battle of Valmy. The First Republic was declared the next day. By the end of 1792, the French had taken over the Austrian Netherlands and parts of Germany.

On January 17, 1793, the king was found guilty of "conspiracy against public liberty" and sentenced to death. He was beheaded on January 21. This act led Britain and the Netherlands to declare war on France.

The Reign of Terror (1793–1794)

The first half of 1793 was difficult for the new French Republic. French armies were pushed out of Germany and the Austrian Netherlands. Prices rose, and poor workers, called sans-culottes, rioted. Some areas also saw anti-revolutionary actions. This led the radical Jacobins to take power. They were supported by the sans-culottes in Paris.

The government became much more extreme. They started the "levy-en-masse," which meant all healthy men aged 18 and older had to serve in the military. This allowed France to create much larger armies than its enemies, and the war started to turn in their favor.

The Committee of Public Safety came under the control of Maximilien Robespierre. The Jacobins then started the Reign of Terror. At least 1,200 people were executed, mostly by guillotine, for supposedly being against the revolution. In October, the queen was also beheaded. In 1794, Robespierre had both extreme radicals and moderate Jacobins executed. But this made him lose popular support. Georges Danton was executed for saying there were too many executions. There were even attempts to get rid of organized religion and replace it with a "Festival of Reason."

The Thermidorian Reaction (1794–1795)

On July 27, 1794, the French people rebelled against the extreme actions of the Reign of Terror. This event was called the Thermidorian Reaction. Moderate members of the Convention removed Robespierre and other leaders of the Committee of Public Safety. They were all executed without a trial. This ended the most extreme part of the Revolution. A new, more conservative constitution was approved in August 1795 and took effect in September.

The Directory (1795–1799)

The new constitution created the Directoire, a new government with two legislative bodies. It was more conservative and aimed to restore order, keeping the sans-culottes and lower classes out of politics.

By 1795, France had again conquered the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine, adding them to France. The Dutch Republic and Spain were defeated and became French allies. However, at sea, the French navy was no match for the British.

Napoleon Bonaparte was given command of an army to invade Italy in 1796. This young general defeated the Austrian and Sardinian forces. He even negotiated a peace treaty without the Directory's full approval. France's control over the Austrian Netherlands and the Rhine's left bank was recognized, as were the new republics Napoleon created in northern Italy.

Although the first war ended in 1797, a second war started in May 1798 when France invaded Switzerland and parts of Italy. Napoleon convinced the Directory to let him lead an expedition to Egypt. His goal was to cut off Britain's trade route to India. He left in May 1798 with 40,000 men. But the expedition failed when the British fleet, led by Horatio Nelson, destroyed most of the French ships in the Battle of the Nile. The French army was stuck in Egypt.

The Consulate (1799–1804)

Napoleon himself managed to escape back to France. In November 1799, he led a coup d'état and made himself First Consul, the most powerful leader. (His troops in Egypt surrendered to the British in 1801 and were sent back to France.)

By this time, the War of the Second Coalition was ongoing. France suffered several defeats in 1799. But once Napoleon returned, he began to turn the tide. In 1801, peace treaties were signed with Austria and Russia, and in 1802, with Britain.

The First Empire (1804–1814)

By 1802, Napoleon was named First Consul for life. His actions led to renewed war with Britain in 1803. The next year, he declared himself emperor in a grand ceremony at Notre Dame Cathedral. He even took the crown from the Pope and placed it on his own head. He gained more power and worked to rebuild France and its systems.

The First French Empire (1804–1814) was a time when France controlled and reorganized much of Europe through the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon also created the Napoleonic Code, a new legal system. His empire became more strict, limiting freedom of the press and assembly. Religious freedom was allowed, but Christianity and Judaism were the only officially recognized faiths. Napoleon also brought back a form of nobility, but it wasn't as grand as the old monarchy. Despite his strict rule, other European countries still saw him as a symbol of the Revolution.

By 1804, only Britain remained outside French control and actively encouraged resistance against France. In 1805, Napoleon gathered a huge army to invade Britain, but he never found the right moment to cross the sea. Three weeks later, the British destroyed the French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar. After this, Napoleon tried to defeat Britain through economic warfare. He started the Continental System, which blocked all trade with Britain for France's allies and controlled countries.

Portugal, a British ally, was the only European country that openly refused to join. After treaties in 1807, France invaded Portugal through Spain to close this gap in the Continental System. British troops arrived in Portugal, forcing the French to leave. Another invasion the next year brought the British back. Napoleon then decided to remove the Spanish king and put his brother, Joseph, on the throne. This caused the Spanish people to rebel, starting the Peninsular War. This war gave Britain a foothold in Europe and tied up many French resources, contributing to Napoleon's eventual defeat.

Napoleon was at his most powerful between 1810 and 1812. Most European countries were either his allies, under his control, or directly part of France. After defeating Austria in 1809, Europe was mostly peaceful for two and a half years, except for the war in Spain. Napoleon even married an Austrian princess, who gave birth to his son in 1811.

However, the Continental System failed. It hurt European countries more than Britain. Russia, in particular, was unhappy with the trade ban. In 1812, Russia reopened trade with Britain, which led to Napoleon's invasion of Russia. This disastrous campaign caused all the countries under French rule to rise up. In 1813, Napoleon had to force younger boys and less fit men into his army. The quality of his troops declined, and people in France grew tired of war. The allies also had many more soldiers.

Throughout 1813, the French were pushed back. By early 1814, British troops were in France. Allied armies reached Paris in March, and Napoleon gave up his title as emperor. Louis XVIII, the brother of Louis XVI, became king. France received a fair peace deal, returning to its 1792 borders and not having to pay war damages.

After 11 months in exile on the island of Elba, Napoleon escaped and returned to France. He was welcomed with great excitement. Louis XVIII fled Paris. But Napoleon couldn't bring back the extreme revolutionary ideas that would have given him mass support. The excitement faded, and since the allies refused to negotiate, he had to fight. At Waterloo, Napoleon was completely defeated by the British and Prussians. He gave up his title again and was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821.

The Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830)

Louis XVIII was put back on the throne a second time by the allies in 1815, ending over two decades of war. He promised to rule as a king with limited power under a constitution. After Napoleon's brief return in 1815, a harsher peace treaty was forced on France. It returned to its 1789 borders and had to pay war damages. Allied troops stayed in France until the money was paid. There were some purges of Napoleon's supporters from the government and military, and a short "White Terror" in southern France killed about 300 people. Otherwise, the change was mostly peaceful.

Even though the old ruling class returned, they didn't get back their lost lands. They couldn't reverse most of the big changes that had happened in French society and the economy. Economic changes, which started before the revolution, had grown stronger during the years of unrest. Power had shifted from noble landowners to city merchants. Napoleon's reforms, like the Napoleonic Code and efficient government, also stayed in place. These changes created a strong central government that was financially stable. France quickly paid off its war debts, and the foreign troops left quietly.

In 1823, France sent troops to Spain to help King Ferdinand VII during a civil war. The French troops quickly took Madrid from the rebels and left. Despite worries, France showed no signs of returning to an aggressive foreign policy and was accepted back into the group of major European powers in 1818.

Louis XVIII mostly accepted that France had changed a lot. However, he faced pressure from extreme royalists, called the Ultras, who wanted to undo more of the revolution's changes. In 1815, the Ultras, who controlled the parliament, banished anyone who had voted for Louis XVI's death. Louis XVIII had to dissolve this parliament in 1816 because he feared a popular uprising. Liberals then governed until 1820, when the king's nephew, a supporter of the Ultras, was assassinated. This brought the Ultras back to power.

Louis XVIII died on September 16, 1824, and his brother, Charles X of France, became king. Charles X followed the "ultra" conservative path but was less skilled at building support. He severely limited freedom of the press. He also paid money to the families of nobles whose property had been taken during the Revolution. In 1830, unhappiness with these changes and Charles X's choice of an extreme Ultra as prime minister led to his overthrow.

The Restoration period didn't bring back the old system completely. Too much had changed. The ideas of equality and freedom from the revolution remained strong. The economic changes had made urban merchants more powerful than noble landowners. Napoleon's administrative reforms, like the Napoleonic Code, also stayed. France became a respected major power again. There was a new focus on helping others and on religious devotion. France also began to rebuild its overseas empire on a small scale.

The July Monarchy (1830–1848)

Charles X was overthrown in an uprising in Paris, known as the 1830 July Revolution (or "Les trois Glorieuses" - The three Glorious days - of July 27, 28, and 29). Charles had to flee, and Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, a cousin of Louis XVI, became king. Louis-Philippe ruled as "King of the French" instead of "King of France," showing that his power came from the people, not from God. He also brought back the Tricolor flag, a symbol of the revolution, instead of the white Bourbon flag. The July Monarchy (1830–1848) was a time when the wealthy middle class had the most political power. Louis-Philippe understood that these rich citizens had put him in power, and he kept their interests in mind.

Louis-Philippe, who had once supported liberal ideas, avoided the grand style of the old kings and surrounded himself with merchants and bankers. However, the July Monarchy was still a time of unrest. Many royalists wanted to bring back the Bourbons. On the other side, republicans and socialists remained strong forces. Towards the end of his rule, Louis-Philippe became very rigid. His prime minister, François Guizot, became very unpopular, but Louis-Philippe refused to remove him. This led to the Revolutions of 1848, which ended the monarchy and created the Second Republic.

In the early years of his rule, Louis-Philippe seemed to support reforms. The government's power came from the Charter of 1830, which promised religious equality, a stronger National Guard, electoral reform, and less royal power. However, many of these policies actually helped the government and the wealthy middle class, rather than truly promoting equality for all French people. So, while the July Monarchy appeared to be moving towards reform, it was often just an illusion.

During the July Monarchy, the number of people who could vote roughly doubled, from 94,000 to over 200,000 by 1848. But this was still less than one percent of the population. Since voting rights were based on how much tax you paid, only the wealthiest could vote. This meant the wealthy middle class gained more power in parliament. This also prevented radical groups from gaining power.

The reformed Charter of 1830 limited the king's power, taking away his ability to propose laws and limiting his executive power. However, Louis-Philippe still believed the king should be more than just a figurehead. He was very active in politics. He appointed Casimir Pierre Perier, a conservative banker, as prime minister. Perier helped shut down many republican secret societies and labor unions. He also oversaw the breaking up of the National Guard when it seemed too supportive of radical ideas. He did all this with the king's approval.

This conservative trend continued under Perier and the Minister of the Interior, François Guizot. The monarchy quickly realized that radical and republican ideas threatened it. So, in 1834, they made the term "republican" illegal. Guizot closed republican clubs and publications. Republicans in the government were pushed out. Louis-Philippe, not trusting the National Guard, increased the size of the army to ensure its loyalty.

There were always two groups in the government: liberal conservatives like Guizot and liberal reformers like Adolphe Thiers. But the reformers never gained much power. Guizot's government was known for cracking down on republicanism and dissent. It also had pro-business policies, including tariffs that protected French businesses. The government gave railway and mining contracts to its wealthy supporters and even helped pay for some of the start-up costs. Workers had no legal right to form unions or ask for better pay or hours. So, the July Monarchy generally hurt the lower classes. Guizot famously told those who couldn't vote to "enrichissez-vous" – enrich yourself. The king himself wasn't very popular by the mid-1840s and was often called the "crowned pear" because of his appearance.

There was a lot of admiration for Napoleon during this time. In 1841, his body was brought from Saint Helena and given a grand reburial in France.

Louis-Philippe followed a peaceful foreign policy. Shortly after he became king in 1830, Belgium revolted against Dutch rule and became independent. The king refused to intervene there or in any other military actions outside France. The only exception was a war in Algeria, which Charles X had started just before he was overthrown. Louis-Philippe's government decided to continue the conquest of Algeria, which took over a decade. By 1848, Algeria was declared a part of France.

The Second Republic (1848–1852)

The Revolution of 1848 had a big impact across Europe. Popular revolts against strict governments broke out in Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Italy. Economic problems and bad harvests in the 1840s added to the unhappiness.

In February 1848, the French government banned political fundraising dinners where critics of the government met. This led to protests and riots in Paris. An angry crowd went to the royal palace, and the king gave up his throne and fled to England. The Second Republic was then declared.

The revolution in France brought together groups with very different goals. The middle class wanted voting reforms. Socialist leaders wanted a "right to work" and national workshops (a kind of social welfare). Moderates wanted a middle ground. Tensions grew, and in June 1848, a working-class uprising in Paris killed 1,500 workers and ended the dream of a social welfare constitution.

The constitution of the Second Republic, approved in September 1848, had problems. It didn't allow for easy solutions when the President and the Assembly disagreed. In December 1848, Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, was elected President. In 1851, using the excuse of political deadlock, he staged a coup d'état. Finally, in 1852, he declared himself Emperor Napoléon III of the Second Empire.

The Second Empire (1852–1870)

France was ruled by Emperor Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870. His government was strict in its early years, limiting freedom of the press and public meetings. This era saw a lot of industrial growth, city development (including the huge rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann), and economic success. However, Napoleon III's foreign policies would lead to disaster.

In 1852, Napoleon said, "The Empire is peace," but he didn't follow a peaceful foreign policy for long. Just months after becoming president in 1848, he sent French troops to stop a short-lived republic in Rome, and they stayed there until 1870. France's overseas empire grew, gaining land in Indochina, West and Central Africa, and the South Seas. This was helped by new large banks in Paris that funded overseas expeditions. The Suez Canal was opened by Empress Eugénie in 1869, a great achievement by a Frenchman. Still, Napoleon III's France was behind Britain in colonial matters. His efforts to outdo Britain and America in other parts of the world ended badly.

In 1854, the emperor allied with Britain and the Ottoman Empire against Russia in the Crimean War. Afterward, Napoleon got involved in Italian independence. He wanted to make Italy "free from the Alps to the Adriatic" and fought a war with Austria in 1859. After French victories, France and Austria signed a peace treaty. Austria gave Lombardy to Napoleon III, who then gave it to Victor Emmanuel. In exchange for France's help, Piedmont gave its regions of Nice and Savoy to France in 1860.

Napoleon then turned his attention to the Western Hemisphere. He supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War until Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862. Since this made it impossible to support the South without also supporting slavery, the emperor backed off. However, he was also involved in Mexico, which had refused to pay back loans from France, Britain, and Spain. These three countries sent an expedition to Mexico in 1862. Britain and Spain soon left when they realized Napoleon's full plans. French troops occupied Mexico City in 1863 and set up a puppet government led by the Austrian archduke Maximilian, who was declared Emperor of Mexico. This went against the Monroe Doctrine, but Napoleon thought the United States was too busy with its Civil War to react. The French could never fully defeat the forces of the ousted Mexican president Benito Juárez. In 1865, the American Civil War ended. The United States, with a huge, experienced army, demanded that the French leave or prepare for war. They quickly left, but Maximilian tried to stay in power. He was captured and shot by the Mexicans in 1867.

Public opinion became important as people grew tired of the strict government in the 1860s. Napoleon III began to ease censorship and allow more public meetings and the right to strike. As a result, radical ideas grew among industrial workers. Unhappiness with the Second Empire spread quickly as the economy started to decline. Napoleon's risky foreign policy was also criticized. To calm the liberals, Napoleon proposed a fully parliamentary government in 1870, which gained huge support. However, he never got to implement this, because by the end of the year, the Second Empire had collapsed.

Napoleon's focus on Mexico prevented him from getting involved in wars in 1864 and 1866, which saw Prussia become the main power in Germany. After these wars, tensions between France and Prussia grew, especially in 1868 when Prussia tried to put a German prince on the Spanish throne.

The Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck provoked Napoleon into declaring war on Prussia in July 1870. French troops were quickly defeated. On September 1, the main French army, with the emperor, was trapped at Sedan and forced to surrender. A republic was quickly declared in Paris, but the war continued. Since it was clear Prussia would demand land, the temporary government vowed to keep fighting. The Prussians surrounded Paris, and new French armies failed to break the siege. Paris faced severe food shortages, to the point where even zoo animals were eaten. In January 1871, as the city was being bombed, King William of Prussia was declared Emperor of Germany at Versailles. Soon after, Paris surrendered. The peace treaty was harsh. France gave Alsace and Lorraine to Germany and had to pay 5 billion francs in damages. German troops would stay in France until the money was paid. Meanwhile, the defeated Napoleon III went into exile in England, where he died in 1873.

The Third Republic (from 1870)

The Third Republic began with France occupied by foreign troops, its capital in a socialist uprising (the Paris Commune), and two regions (Alsace-Lorraine) taken by Germany. Feelings of national guilt and a desire for revenge were major concerns for France for the next two decades. Yet by 1900, France had rebuilt many economic and cultural ties with Germany, and few French people still dreamed of "revenge." No French political party even mentioned Alsace-Lorraine in its plans anymore.

Napoleon's rule ended suddenly when he declared war on Prussia in 1870. He was defeated and captured at Sedan. He gave up his throne on September 4, and the Third Republic was declared that same day in Paris.

The French legislature established the Third Republic, which lasted until the military defeat of 1940. On September 19, the Prussian army arrived in Paris and surrounded the city. The city suffered from cold and hunger; Parisians even ate animals from the zoo. In January, the Prussians began bombing the city. Paris finally surrendered on January 28, 1871. The Prussians briefly occupied the city and then took positions nearby.

The Paris Commune (1871)

A revolt broke out on March 18 when radical soldiers from the Paris National Guard killed two French generals. French government officials and the army quickly moved to Versailles. A new city council, the Paris Commune, dominated by anarchists and radical socialists, was elected and took power on March 26. It tried to put in place a bold and radical social program.

The Commune proposed separating the Church and the state, making all Church property state property, and removing religious teaching from schools. Churches could only continue religious activities if they kept their doors open for public political meetings in the evenings. Other planned laws aimed to make further education and technical training free for everyone. However, these programs were never fully carried out due to lack of time and resources. The Vendôme Column, a symbol of Napoleon's empire, was pulled down.

The Paris Commune only held power for two months. Between May 21 and 28, the French army recaptured the city in fierce fighting, known as "la semaine sanglante" or "bloody week." During the street fighting, the Communards were greatly outnumbered. They lacked good leaders and had no plan for defending the city, so each neighborhood had to defend itself. Their military commander died on May 26. In the final days, the Communards set fire to important government buildings and executed hostages, including the archbishop of Paris.

The army lost 837 dead and 6,424 wounded from April through Bloody Week. Nearly 7,000 Communards were killed in battle or executed by firing squads afterward. About 10,000 Communards escaped and went into exile. Forty-five thousand prisoners were taken after the Commune fell. Most were released, but 23 were sentenced to death, and about 10,000 were sent to prison or exiled to colonies. All prisoners and exiles were pardoned in 1879 and 1880, and most returned to France, where some were elected to parliament.

Royalist Control (1871–1879)

So, the Republic was born from two defeats: against the Prussians and against the revolutionary Commune. The suppression of the Commune was very bloody. Thousands were killed, imprisoned, or exiled. Paris remained under military rule for five years.

Besides these defeats, the Republican movement also had to face those who wanted to bring back the old system. Both the Legitimist and Orléanist royalists rejected republicanism. They saw it as going against France's traditions and religion. This struggle lasted until at least 1877, which finally led to the resignation of the royalist Marshal MacMahon in January 1879. The death of Henri, comte de Chambord in 1883, who refused to give up the old royal symbols, convinced many Orleanists to support the Republic. Most Legitimists left politics or became less important.

The "Radicals" (1879–1914)

The early Republic was led by pro-royalists, but republicans (called "Radicals") and supporters of Napoleon fought for power. From 1879 to 1899, moderate republicans and former "radicals" (like Léon Gambetta) gained power. These were called the "Opportunists." Their control allowed for the 1881 and 1882 Jules Ferry laws on free, mandatory, and non-religious education.

However, the moderates became deeply divided over the Dreyfus affair. This allowed the Radicals to gain power from 1899 until World War I. During this time, crises like the potential "Boulangist" coup in 1889 showed how fragile the republic was. The Radicals' policies on education (ending local languages, mandatory schooling), military service, and controlling workers helped reduce internal disagreements and regional differences. Their involvement in the Scramble for Africa and gaining overseas lands (like French Indochina) created ideas of French greatness. Both these processes changed France from a country of different regions into a modern nation-state.

In 1880, Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue, Karl Marx's son-in-law, created the first Marxist party in France. Later, different socialist groups formed and eventually united in 1905 into the "French section of the Second International" (SFIO).

Bismarck had supported France becoming a republic in 1871, knowing it would isolate the defeated nation among mostly monarchical European countries. To break this isolation, France worked hard to win over Russia and the United Kingdom. First, through the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, then the 1904 Entente Cordiale with the U.K., and finally, with the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907, this became the Triple Entente. This alliance eventually led France and the U.K. to enter World War I as allies when Germany declared war on Russia.

Distrust of Germany, faith in the army, and anti-Jewish feelings among some French people combined to make the Dreyfus affair a very serious political scandal. This was the unfair trial and conviction of a Jewish military officer for treason. The nation was split between those who supported Dreyfus and those who were against him. Far-right Catholic activists made the situation worse, even when proof of Dreyfus's innocence came out. The writer Émile Zola published a strong article about the injustice and was himself convicted of libel. Once Dreyfus was finally pardoned, the progressive government passed the 1905 laws on laïcité, which completely separated church and state and took away most of the churches' property rights.

The period at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century is often called the Belle Époque (Beautiful Era). It's known for cultural innovations and popular entertainment (like cabaret, cancan, cinema, and new art forms like Impressionism and Art Nouveau). However, France was still divided internally by religion, class, regional differences, and money. Internationally, France sometimes came close to war with other powerful nations, including Great Britain. Yet, from 1905 to 1914, the French repeatedly elected left-wing, peaceful parliaments, and French diplomacy worked to solve problems peacefully. France was caught unprepared by Germany's declaration of war in 1914. The human and financial costs of World War I would be terrible for the French.

Images for kids

-

A 1910 map showing French control in much of North and West Africa as well as Madagascar

-

Contemporary illustration of Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand's trek across Africa

-

Claude Monet, Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), 1872

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |