Jacques Necker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacques Necker

|

|

|---|---|

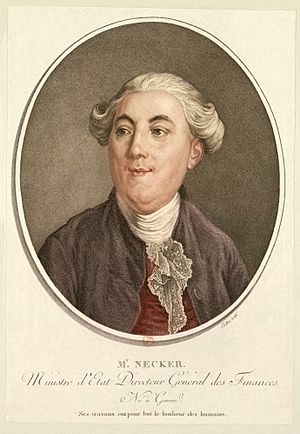

Portrait by Joseph Duplessis, c. 1781

|

|

| Chief Minister of the French Monarch | |

| In office 16 July 1789 – 3 September 1790 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Baron of Breteuil |

| Succeeded by | Count of Montmorin |

| In office 25 August 1788 – 11 July 1789 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Archbishop de Brienne |

| Succeeded by | Baron of Breteuil |

| Controller-General of Finances | |

| In office 25 August 1788 – 11 July 1789 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Charles Alexandre de Calonne |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Foullon de Doué |

| Director-General of the Royal Treasury | |

| In office 29 June 1777 – 19 May 1781 |

|

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Louis Gabriel Taboureau des Réaux |

| Succeeded by | Jean-François Joly de Fleury |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 September 1732 Geneva, Republic of Geneva |

| Died | 9 April 1804 (aged 71) Geneva, Léman, France |

| Spouse |

Suzanne Curchod

(m. 1764; died 1794) |

| Children | Germaine Necker |

| Signature |  |

Jacques Necker (born September 30, 1732 – died April 9, 1804) was a banker and important government official from Geneva. He worked as the finance minister for King Louis XVI in France. Necker wanted to make changes, but his new ideas sometimes made people unhappy. He believed in a monarchy where the king's power was limited by laws. He was also an expert in how countries manage their money.

Necker was in charge of France's money from 1777 to 1781. He is famous for doing something no one had done before: in 1781, he showed the public France's budget. This was a big deal because, in a country ruled by an absolute king, money matters were always kept secret. Necker was fired a few months later. By 1788, France was in a huge money crisis because of its debts. So, Necker was called back to work for the king. But he was fired again on July 11, 1789. This firing helped cause the Storming of the Bastille, a major event in the French Revolution. Just two days later, the king and the assembly asked Necker to return. He came back to France as a hero and tried to speed up tax reform. But the new assembly didn't agree with him. He resigned in September 1790, and by then, most people didn't care much.

Contents

Early Life and Banking Career

Jacques Necker was born in Geneva on September 30, 1732. His father was a lawyer and a professor. After studying in Geneva, Necker moved to Paris in 1748. He started working as a clerk in a bank. He quickly learned Dutch and English. One day, he filled in for a senior clerk and made a lot of money very quickly by trading on the stock market.

In 1762, Necker became a partner in the bank. He was very good at making money. For example, before the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, he bought British bonds and wheat. He sold them later for a big profit.

Necker fell in love with Suzanne Curchod, who was a governess. They married in 1764. In 1766, they had a daughter named Anne Louise Germaine. She later became a famous writer known as Madame de Staël.

Madame Necker wanted her husband to get a public job. So, he became a director of the French East India Company. This company was involved in a big political debate at the time. Necker showed his financial skills by managing the company well. He even wrote a paper in 1769 to defend the company. The company went bankrupt in 1769, and Necker bought its ships and goods.

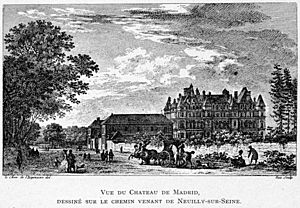

From 1768 to 1776, Necker loaned money to the French government. His wife convinced him to sell his share in the bank in 1772. In 1773, Necker won an award for a paper praising Jean-Baptiste Colbert, a minister of Louis XIV. Necker had become very wealthy. He even owned a summer home called Château de Madrid.

In 1775, Necker wrote a book where he disagreed with economists called physiocrats. These economists believed in "laissez-faire" policies, meaning the government should not interfere with the economy. Necker questioned these ideas, especially those of Turgot, who was the finance minister. Turgot was fired in May 1776. On October 22, 1776, Necker was appointed "Director of the Royal Treasury." Because he was Protestant, he could not be the "Controller-General of Finances."

Necker as Finance Minister of France

On June 29, 1777, Necker became the director-general of the royal treasury. He refused to take a salary. He became popular by trying to make taxes fairer. He got rid of some taxes and set up pawnshop-like places to help people borrow money. Necker tried to fix the country's messy budget. He cut down on unnecessary jobs and pensions. He and his wife also worked to improve hospitals and prisons. In April 1778, he even gave 2.4 million livres of his own money to the royal treasury.

Necker wanted to create local assemblies to help reform the old system of government. He succeeded in setting up these assemblies in a few areas, with an equal number of members from the common people.

His main financial strategy was to use loans to pay off France's debt instead of raising taxes. He also brought back the collection of indirect taxes by private companies, but he made sure they were watched more closely. The American Revolutionary War was popular in France, but Necker worried about its cost. France was paying for the war mostly with loans. He warned that this would hurt the French budget. The ministers of War and Navy didn't like him. In September 1780, Necker offered to resign, but the King refused.

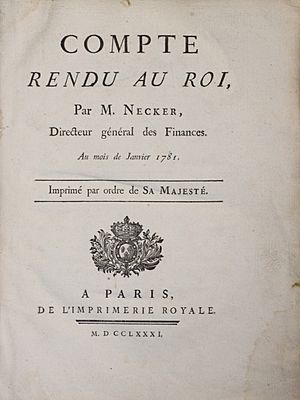

The Compte rendu au roi (Report to the King)

By 1781, France was in financial trouble. As director-general, Necker was blamed for the high debt from the American Revolution. Some people attacked him for being foreign, for his religion, and for his economic choices. Necker decided to make the country's financial report, called the Compte rendu au roi, public. This was a very bold move.

In this report, Necker showed the government's income and spending. It was the first time royal finances were made public. He wanted to inform the public and get them interested in how the government spent money. Before this, people didn't think government money was their business. But the Compte rendu changed that.

Some powerful people, like Maurepas and Vergennes, were jealous or thought Necker was a revolutionary. Necker said he would resign unless he was given the full power of a minister and a seat on the King's Council. Maurepas and Vergennes said they would resign if that happened. So, Necker was fired on May 19, 1781. Many people were sad to see him go. Even other European leaders, like Joseph II and Catherine the Great, expressed their support.

After being fired, Necker bought an estate in Coppet, Switzerland. He spent his retirement writing about law and economics. His most famous work from this period was Traité de l'administration des finances de la France (1784). This book was very popular, selling 80,000 copies.

The Necker family returned to Paris. France was facing national bankruptcy. The new finance minister, Calonne, called an Assembly of notables to try and force through tax reforms. This assembly had not met since 1626. Calonne claimed Necker's financial reports were false and misleading. He said Necker was to blame for the deficit because he hadn't raised taxes. However, Calonne himself got into financial trouble and was fired in April 1787. Necker then publicly defended himself against Calonne's accusations. Two days later, King Louis XVI banished Necker from Paris for this public argument.

After two months, Necker was allowed to return. He published more writings about his financial report. The next finance minister, Loménie de Brienne, resigned after only fifteen months.

On September 7, 1788, Paris was facing a food shortage. Necker stopped the export of grain and bought a lot of wheat. He tried to solve the problem, but it was very difficult. In 1788, Necker was fired again. Queen Marie-Antoinette took credit for convincing the king to do this, believing Necker would reduce the king's power.

But on August 25 or 26, Necker was called back to office. This time, he insisted on being called the Controller-General of Finances and having access to the royal council. He was also appointed Chief minister of France. He immediately reversed a decision that forced bondholders to accept paper money instead of real money. This made government bonds go up in value. He also banned the export of grain again.

Necker tried to get loans from Dutch bankers to help France's debt. He wanted a more limited monarchy, similar to England's system. Some historians believe Necker helped weaken the old system, but he couldn't stop the revolution from happening.

The Only Non-Noble Minister

Necker managed to double the number of representatives for the Third Estate (the common people). This meant the Third Estate had as many deputies as the other two groups (nobles and clergy) combined. On May 5, 1789, Necker gave a three-hour speech to the Estates-General. He talked about France's financial problems, the idea of a constitutional monarchy, and the need for reforms. He asked the representatives to put aside their own interests and think about the good of the whole country.

Necker seemed to think the Estates-General was there to help the government, not to change it completely. Two weeks later, he tried to convince the king to adopt a constitution like England's. He strongly advised the king to make necessary changes before it was too late. Necker warned the king that if the nobles and clergy didn't give in, the Estates-General would fail, taxes wouldn't be paid, and the government would go bankrupt.

On June 17, 1789, the new National Assembly declared all existing taxes illegal. Necker was very worried about this. On July 11, the king told Necker to leave the country right away. When people heard this news the next day, they were furious. Crowds carried statues of Necker through the streets. This anger, along with the fear of a counter-revolution, led citizens to take up arms and storm the Bastille on July 14.

The king and the Assembly quickly called the very popular Necker back to his position on July 16. Necker returned, knowing he was going back into a difficult situation. His replacement, Joseph Foullon de Doué, had been executed on July 22. Necker's return to Versailles on July 29 was celebrated. He asked for a pardon for Baron de Besenval, who had been imprisoned.

On August 4, 1789, the National Assembly abolished Feudalism. Necker noted that tax collectors were struggling.

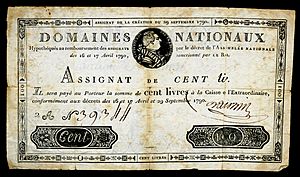

Assignats (Paper Money)

Necker found himself powerless as tax money quickly dried up. The country's credit system was ruined. By September, the treasury was empty. Some people, like Marat, even accused Necker of causing a famine by buying up all the grain.

Talleyrand, a bishop, suggested that "national goods" (like church property) should be given back to the nation. In November 1789, church properties were taken by the government. Necker wanted to borrow from a private bank and turn it into a national bank, like the Bank of England, but this failed. It looked like the country would go bankrupt.

On December 21, 1789, a decree was passed to issue 400 million assignats. These were like certificates of debt, worth 1,000 livres each, with interest. They were backed by the sale of national properties. Once an assignat was used to buy property, it was supposed to be destroyed.

In January 1790, Necker tried to have Jean-Paul Marat arrested for supporting the poor. Marat had to flee to London. In March 1790, the management of church property was given to local governments. People started pushing for more assignats to be issued, in smaller amounts, to be used as regular money. On April 17, 1790, new notes of 200 and 300 livres were declared legal tender (official money), but their interest rate was lowered. The idea was that assignats would make up for the lack of coins and help businesses.

In May 1790, feudal and church properties were sold using assignats. Some people, especially those who supported the king, were against this. Many taxes from the previous year still hadn't been collected. Necker asked his banker friends in Geneva to help pay the government's debts, but the Assembly refused. Necker was constantly attacked by newspapers and politicians. Mirabeau, a powerful figure, accused Necker of trying to control all finances.

By the end of August, the government was in trouble again. The money from the first assignats was gone. The Assembly decided to issue another 1.9 billion assignats. Necker tried to stop this, saying it would cause terrible problems. He suggested other ways to raise money. But he was not supported by Mirabeau, who wanted "national money." Necker resigned on September 3. He had managed to reduce the new issue of assignats from 1.9 billion to 800 million, but the constant attacks led to his resignation. He didn't resign because the assignats became legal tender, but because of the large amount issued and the loss of trust in parliament.

The Assembly decided to take direct control of the public treasury. Necker predicted that the paper money would soon become worthless. His efforts to keep the financial situation stable failed. His popularity disappeared, and he resigned with a damaged reputation. He left two million livres in the public treasury.

Retirement

Necker was suspected of being against the revolution. He traveled to Coppet Castle in Switzerland. There, he spent his time studying economics and law. In late 1792, he wrote a paper about the trial of King Louis XVI. The Neckers were not very welcome in Geneva. Many French people who had left France thought they were too revolutionary. Many Swiss revolutionaries thought they were too conservative.

Necker's name was put on a list of "Émigrés" (people who had fled France). This meant he didn't get any interest on the money he had left in the French treasury. His house in Paris and his estate were taken by the French government. His wife, Madame Necker, became mentally ill. She had always thought she was sick and wanted to be embalmed and displayed after her death.

Necker continued to live under the care of his daughter, Germaine. By 1794, France was flooded with fake assignats. But Necker's time as a major political figure was over. His books had little political impact in France, though they were read abroad. In 1795, Germaine moved to Paris, but she often returned to Coppet and started a famous intellectual group there.

In March 1798, the French army invaded Switzerland. Necker was treated with respect when the army passed his home. In July 1798, his name was removed from the list of Émigrés. His house in Paris was sold. In June 1800, Necker met with Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon told him about his plans to bring back a monarchy in France. Necker's book, "Last Views on Politics and Finance" (1802), upset Napoleon. Napoleon even threatened to exile Madame de Staël from Paris because of her father's book.

Even though Necker had never been a republican, he later thought about creating a strong republic in France. He predicted that a certain government body would be removed, which later happened. His claim for the two million livres he left in the treasury was not recognized by the government. Necker was buried next to his wife in the garden of Coppet Castle.

Some historians believe that Necker has not been treated fairly by history. His statues were destroyed during the revolution, just like those of other temporary popular figures.

Family Life

In 1786, Necker's daughter Germaine married Erik Magnus Staël von Holstein. She became a very important writer and a strong opponent of Napoleon Bonaparte. After Necker's death, his daughter published a book about his private life. His grandson, Auguste de Staël, later edited all of Jacques Necker's writings.

Necker's nephew, Jacques Necker (1757–1825), was a botanist. He married Albertine Necker de Saussure. They took care of their uncle after his wife died in 1794. Their son, Louis Albert Necker, became a famous geologist.

Places Named After Jacques Necker

- Necker Hospital for Children in Paris, France

- Necker Island (Northwestern Hawaiian Islands)

- Necker middle school in Coppet, Switzerland

Works

- Réponse au mémoire de M. l'abbé Morellet sur la Compagnie des Indes, 1769

- Éloge de Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1773

- Sur la Législation et le commerce des grains, 1775

- Mémoire au roi sur l'établissement des administrations provinciales, 1776

- Lettre au roi, 1777

- Compte rendu au roi, 1781

- De l'Administration des finances de la France, 1784, 3 vol. in-8°

- Correspondance de M. Necker avec M. de Calonne. (29 janvier-28 février 1787), 1787

- De l'importance des opinions religieuses, 1788

- De la Morale naturelle, suivie du Bonheur des sots, 1788

- Supplément nécessaire à l'importance des opinions religieuses, 1788

- Sur le compte rendu au roi en 1781 : nouveaux éclaircissements, 1788

- Rapport fait au roi dans son conseil par le ministre des finances, 1789

- Derniers conseils au roi, 1789

- Hommage de M. Necker à la nation française, 1789

- Observations sur l'avant-propos du « Livre rouge », v. 1790

- Opinion relativement au décret de l'Assemblée nationale, concernant les titres, les noms et les armoiries, v. 1790

- Sur l'administration de M. Necker, 1791

- Réflexions présentées à la nation française sur le procès intenté à Louis XVI, 1792

- Du pouvoir exécutif dans les grands États, 1792.

- De la Révolution française, 1796. Tome 1 Tome 2

- Cours de morale religieuse, 1800

- Dernières vues de politique et de finance, offertes à la Nation française, 1802

- Manuscrits de M. Necker, publiés par sa fille (1804)

- Histoire de la Révolution française, depuis l'Assemblée des notables jusques et y compris la journée du 13 vendémiaire an IV (18 octobre 1795), 1821

Images for kids

-

Château de Madrid, Necker's home in Neuilly-sur-Seine

-

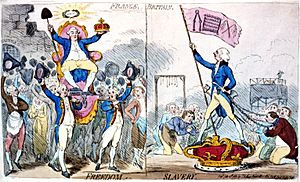

In this 1789 engraving, James Gillray caricatures the triumph of Necker (seated, on left) in 1789, comparing its effects on freedom unfavorably to those of William Pitt the Younger in Britain. France has the caption "Freedom," while Britain has the caption "Slavery."

See also

In Spanish: Jacques Necker para niños

In Spanish: Jacques Necker para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |