William Pitt the Younger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

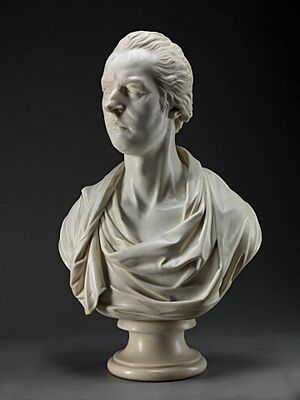

William Pitt

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by John Hoppner

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1804 – 23 January 1806 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Lord Grenville | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 January 1801 – 14 March 1801 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established Himself as Prime Minister of Great Britain |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Great Britain | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 December 1783 – 1 January 1801 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Duke of Portland | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Office abolished Himself as 1st Prime Minister of the United Kingdom |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1804 – 23 January 1806 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Lord Henry Petty | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 December 1783 – 1 January 1801 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Lord John Cavendish | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 July 1782 – 31 March 1783 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Lord John Cavendish | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Lord John Cavendish | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 28 May 1759 Hayes, Kent, England |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 23 January 1806 (aged 46) Putney, England |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Tory | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham Lady Hester Grenville |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Cambridge | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||

William Pitt the Younger (born May 28, 1759 – died January 23, 1806) was an important British leader. He was the youngest person to become Prime Minister of Great Britain. He later became the first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in January 1801. He served as Prime Minister twice: first from 1783 to 1801, and again from 1804 until his death in 1806. He was also in charge of the country's money as Chancellor of the Exchequer during his time as Prime Minister.

People called him "Pitt the Younger" to tell him apart from his father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham. His father had also been Prime Minister and was known as "William Pitt the Elder."

Pitt's time as Prime Minister happened during the rule of King George III. This period was greatly affected by big events in Europe, like the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Even though he is often called a Tory, Pitt described himself as an "independent Whig." He generally did not like the idea of a strict two-party political system.

Pitt was seen as a very good leader who worked to make the government more effective. He raised taxes to help pay for the war against France. He also tried to stop radical ideas from spreading. To deal with the threat of Irish people supporting France, he helped create the Acts of Union 1800. This law joined Ireland with Great Britain. He also tried to give more rights to Catholics, but he was not successful.

Historians say that Pitt was a great Prime Minister because he helped Britain move from old ways to new ones without big problems. He served for over 18 years, making him the second-longest serving British Prime Minister ever, after Robert Walpole.

Contents

Growing Up

Early Education

William Pitt was born on May 28, 1759, in Hayes, Kent. His family was very involved in politics. His father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, was a former Prime Minister. His mother, Hester Grenville, was the sister of another former Prime Minister, George Grenville.

As a child, Pitt was often sick. He was taught at home and quickly became good at Latin and Greek. He started Pembroke College, Cambridge when he was almost 14. There, he studied political ideas, history, and other subjects. He became good friends with William Wilberforce, who would later work with him in Parliament. Pitt was known for his cleverness and gentle sense of humor.

In 1776, because of his health, Pitt was allowed to graduate from Cambridge without taking exams. This was a special rule for sons of noble families. Pitt's father died in 1778. Pitt did not inherit much money because he was a younger son. He studied law and became a lawyer in 1780.

Becoming a Member of Parliament

In 1780, at age 21, Pitt tried to become a Member of Parliament for Cambridge University but lost. He still wanted to be in Parliament. A friend helped him get a seat for a small town called Appleby in January 1781. This was a "pocket borough," meaning a powerful person controlled who got elected there. It's interesting because Pitt later spoke out against these types of unfair elections.

Once in Parliament, Pitt became a strong speaker. He first joined with other Whig politicians, like Charles James Fox. Pitt spoke against the American War of Independence, just like his father had. He also supported ideas to make Parliament fairer and stop corruption in elections.

After the government changed in 1782, Pitt was offered a small job in Ireland, but he turned it down. He wanted a more important role. When William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne became Prime Minister, Pitt joined his government as Chancellor of the Exchequer. This meant he was in charge of the country's money.

Charles James Fox, who became Pitt's political rival, then teamed up with another politician, Lord North. Together, they forced Shelburne's government to resign. King George III did not like Fox. He offered Pitt the job of Prime Minister, but Pitt wisely said no. He knew he didn't have enough support in Parliament yet.

Pitt then joined the group that opposed the new government. He kept pushing for changes to Parliament. He wanted to stop bribery and fix the unfair "rotten boroughs" where very few people could vote. Even though his ideas didn't pass, many people who wanted reform started to see Pitt as their leader.

Rise to Power

Becoming Prime Minister

The government led by Fox and North fell apart in December 1783. This happened after Fox tried to pass a law about the East India Company that the King did not like. The King fired the government and finally made William Pitt Prime Minister.

Pitt was only 24 years old, making him the youngest Prime Minister in British history. Many people thought his government would not last long. But it survived for 17 years!

Pitt tried to include Fox and his friends in his government to make it stronger, but Fox refused. Pitt's new government faced a lot of opposition. In January 1784, Parliament voted against him. But Pitt refused to resign. He had the King's support, and the King did not want Fox to be in power. Pitt also gained support from the House of Lords and from many people across the country.

Pitt became very popular with the public. They called him "Honest Billy." People saw him as a fresh change from the politicians they thought were dishonest. Even though he lost many votes in Parliament, Pitt stayed in office. The number of politicians against him slowly got smaller.

In March 1784, a new election was held. Pitt won a huge victory because he had the King's support and a lot of public support. He was elected to represent Cambridge University, a seat he wanted very much. He would keep this seat for the rest of his life.

First Government

As Prime Minister, Pitt worked on making changes to Parliament. In 1785, he suggested a law to remove the unfair "rotten boroughs" and give more people the right to vote. However, this idea was not passed by Parliament. This was the last time Pitt tried to reform Parliament.

Changes for Colonies

With his government stable, Pitt started to make new laws. One important law was the India Act 1784. This law changed how the East India Company was run and tried to stop corruption. It created a new group called the India Board to watch over the company.

After the American Revolutionary War ended in 1783, the United States would no longer take prisoners from Britain. So, Pitt's government decided to send them to a new place: Australia. In 1786, the first group of ships, called the First Fleet, sailed to Australia. They carried over a thousand settlers, including many prisoners. The Colony of New South Wales was officially started in Sydney in 1788.

Managing Money

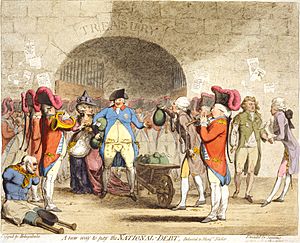

Pitt also had to deal with Britain's huge national debt, which had doubled during the American war. He tried to reduce it by adding new taxes. In 1786, he set up a "sinking fund." This meant £1 million was put aside each year to earn interest. This money would eventually be used to pay off the national debt. By 1792, the debt had gone down.

Pitt was very careful with money. A lot of goods were being smuggled into Britain without taxes being paid. He made it easier for honest traders by lowering taxes on things like tea and tobacco. This helped the government collect more money.

In 1797, Pitt had to stop people from exchanging paper money for gold to protect the country's gold supply. Britain used paper money for over 20 years after this. Pitt also introduced Britain's first ever income tax. This new tax helped make up for money lost from other taxes.

Foreign Relations

Pitt wanted to make alliances in Europe to limit France's power. In 1788, he formed the Triple Alliance with Prussia and Holland. This alliance helped Britain in a disagreement with Spain in 1790.

Pitt was worried about Russia expanding its power in the 1780s. He tried to stop Russia from taking a key fortress from the Ottoman Empire. However, there was a lot of opposition in Parliament to his plan, so he gave up. Later, the French Revolution started, which made Britain and Russia become allies against France.

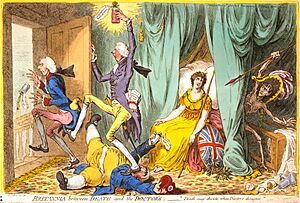

The King's Health

In 1788, King George III became very ill with a mental disorder. If the King couldn't do his job, Parliament would need to choose someone to rule in his place. Everyone agreed that the King's oldest son, George, Prince of Wales, was the only choice. However, the Prince was a supporter of Charles James Fox. If the Prince became ruler, he would likely fire Pitt. Luckily for Pitt, the King recovered in February 1789, just as a law about the regency was about to pass.

Pitt remained Prime Minister after the elections in 1790. In 1791, he helped divide the province of Quebec in Canada into two parts: Lower Canada (mostly French) and Upper Canada (mostly English).

French Revolution and War

At first, some people in Britain liked the French Revolution. This made them want to change Parliament in Britain. But soon, people who wanted reform were called "radicals" and linked to the French revolutionaries. In 1794, Pitt's government tried some reformers for treason, but they were found not guilty.

Parliament then passed strict laws to stop reformers. People who published "seditious" (rebellious) writings were punished. In 1794, the right to habeas corpus (the right to be brought before a judge) was temporarily stopped. Other laws limited public meetings and the formation of groups that wanted political changes.

The war with France was very expensive for Britain. Britain had a small army, so it mostly helped the war effort with its strong navy and by giving money to other countries fighting France.

Fighting Ideas

Throughout the 1790s, the war against France was presented as a fight between French republican ideas and British monarchy. Pitt's government tried to get public support for the war. They showed Britain as an orderly society and France as chaotic. They also tried to link British "radicals" with the French Revolution.

Pitt's government did limit people's freedoms and created a network of spies. People were encouraged to report anyone they thought was a "radical." However, historians say that this was not as harsh as some people claim. There was also a strong movement of people who supported the King and country.

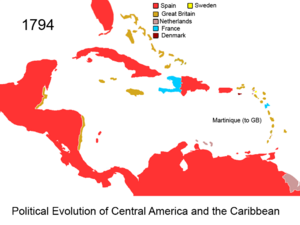

War in the Caribbean

In 1793, Pitt decided to take advantage of the Haitian Revolution to capture St. Domingue, a very rich French colony. He thought this would hurt France and bring St. Domingue into the British Empire. Many British plantation owners in the West Indies were worried about the slave revolt in St. Domingue. They wanted Pitt to restore slavery there so their own slaves wouldn't get ideas about freedom.

British troops landed in St. Domingue in September 1793. They said they were there to protect the white population. But the British wanted to bring back slavery, which made the Haitians fight fiercely. Many British soldiers died from yellow fever. Pitt still sent more troops in 1795 in what he called the "great push."

By 1795, half of the British Army was in the West Indies, mostly in St. Domingue. Pitt believed it was very important for Britain to control St. Domingue, no matter the cost. However, the British attempt to conquer St. Domingue failed. The British left in August 1798. They had spent a lot of money and lost about 100,000 men, mostly to disease. Historians say this effort greatly weakened the British army and hurt Britain's influence in Europe.

Problems in Ireland

In May 1798, there was a big rebellion in Ireland led by the Society of United Irishmen. They wanted Ireland to be independent. Pitt responded very harshly, and about 1,500 rebels were executed. This rebellion made Pitt believe that the Irish Parliament, which was mostly Protestant, could not govern well.

Pitt then pushed for the Acts of Union 1800. This law would make Ireland an official part of the United Kingdom. He thought this would solve the "Irish Question" and prevent France from using Ireland as a base to attack Britain. The Irish Parliament did not want to give up its power. So, Pitt used a lot of money and favors to convince Irish politicians to vote for the Act of Union.

Throughout the 1790s, the Society of United Irishmen grew. They were inspired by the American and French revolutions and wanted Ireland to be a republic. Pitt tried to get the Irish Parliament to ease laws against Catholics, but they refused. In rural Ireland, there was a lot of violence between Catholic and Protestant groups. In 1796, a French invasion of Ireland was stopped only by bad weather. To crush the United Irishmen, Pitt sent troops and set up a network of spies.

In April 1797, sailors in the British navy at Spithead rebelled. They demanded better pay. Pitt agreed to their demands and the King pardoned them. However, a more political mutiny at the Nore in June 1797 was handled more strictly. Pitt refused to negotiate and wanted the leader hanged. In response, Pitt passed laws making it illegal to encourage breaking oaths to the King and further limiting civil liberties.

War Failures

Despite Pitt's efforts, France continued to win battles against the First Coalition of European powers, which fell apart in 1798. A Second Coalition was formed, including Britain, Austria, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire. But this alliance also failed to defeat France. After major defeats in 1800, Britain was left fighting France alone.

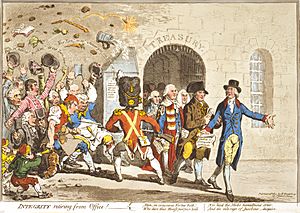

Resignation

After the Acts of Union 1800, Pitt wanted to give more rights to Roman Catholics in Ireland. Catholics made up 75% of the Irish population. However, King George III was strongly against this. He believed it would go against his promise to protect the Church of England. Pitt could not change the King's mind, so he resigned on February 16, 1801. He allowed his friend, Henry Addington, to become the new Prime Minister.

Around the same time, the King became ill again. Pitt continued to do his duties for a short time. Power was officially given to Addington on March 14, when the King recovered.

Pitt supported the new government, but he was not very enthusiastic. He often stayed at his home, Walmer Castle, which was on the coast. From there, he helped organize local volunteer groups to prepare for a possible French invasion. He also encouraged the building of coastal defenses.

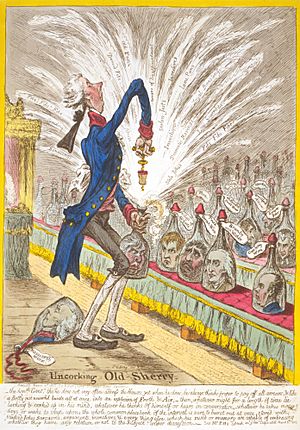

The Treaty of Amiens in 1802 brought a temporary end to the wars with France. But everyone expected the peace to be short. By 1803, war had started again with France, now led by Napoleon Bonaparte. Pitt joined the opposition, criticizing the government's policies. Addington's government lost support and he resigned in April 1804.

Return to Power

Second Government

Pitt became Prime Minister again on May 10, 1804. He wanted to form a government with many different political groups, but King George III refused to include Charles James Fox. Many of Pitt's old supporters also joined the opposition. This made Pitt's second government much weaker than his first.

The British government started to put more pressure on Napoleon. Thanks to Pitt, the United Kingdom joined the Third Coalition. This alliance included Austria, Russia, and Sweden. In October 1805, the British Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, won a huge victory at the Battle of Trafalgar. This battle made sure Britain had control of the seas for the rest of the war.

At a dinner celebrating him, Pitt gave a famous speech. He said, "Europe is not to be saved by any single man. England has saved herself by her efforts, and will, as I trust, save Europe by her example."

However, the Third Coalition failed after major defeats in Europe in October and December 1805. After hearing the news, Pitt looked at a map of Europe and said, "Roll up that map; it will not be wanted these ten years."

Managing Money for War

Pitt was very skilled with money and served as Chancellor of the Exchequer. A key part of his success against Napoleon was using Britain's strong economy. He was able to use the country's factories and money to fight France.

Britain had a population of 16 million, which was less than half of France's 30 million. But Britain used its money to pay for many Austrian and Russian soldiers, helping to balance the numbers.

Britain used its economic power to make the Royal Navy much bigger. The number of ships and sailors greatly increased after the war started in 1793. Britain's economy stayed strong, and businesses made what the military needed. France's navy, however, became much smaller. Smuggling goods into Europe also hurt France's efforts to damage the British economy.

By 1814, the government's budget, largely shaped by Pitt, had grown very large. The national debt also soared. However, many investors and taxpayers supported it, even with higher taxes.

Death

The stress of the war affected Pitt's health. He had been sick since childhood and suffered from gout. On January 23, 1806, Pitt died at his home in Putney. He was not married and had no children.

Pitt had debts when he died, but Parliament agreed to pay them for him. He was given a public funeral and a monument. Pitt's body was buried in Westminster Abbey on February 22.

His first cousin, William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, became the next Prime Minister.

Legacy

William Pitt the Younger was a Prime Minister who made the job of Prime Minister more powerful. He helped define the role of the Prime Minister as the main leader and coordinator of all government departments. After he died, conservatives saw him as a great national hero.

One of Pitt's big achievements was fixing the country's money problems after the American War of Independence. He changed the tax system to collect more money, which helped manage the growing national debt.

Some of Pitt's plans at home were not successful. He failed to get Parliament reformed, or to give full rights to Catholics. He also did not manage to abolish the slave trade during his time, although it was abolished the year after he died. Historians say that by the end of his career, Pitt was very tired from his long time in office and the constant wars.

Historians compare him to his father, William Pitt the Elder. The younger Pitt was a great speaker, like his father. This helped him control Parliament and represent the country during wartime. But the younger Pitt was also very professional and always looked for the best information. He was truly progressive on issues like parliamentary reform, Catholic rights, and trade. He was much better at managing money than his father. His long time in office showed that he could handle the challenges of his time.

See also

In Spanish: William Pitt (el Joven) para niños

In Spanish: William Pitt (el Joven) para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |