Charles James Fox facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles James Fox

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Karl Anton Hickel, 1794

|

|

| Foreign Secretary | |

| In office 7 February 1806 – 13 September 1806 |

|

| Prime Minister | William Grenville |

| Preceded by | The Lord Mulgrave |

| Succeeded by | Viscount Howick |

| In office 2 April 1783 – 19 December 1783 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Duke of Portland |

| Preceded by | The Lord Grantham |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Temple |

| In office 27 March 1782 – 5 July 1782 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Marquess of Rockingham |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Stormont (Northern Secretary) |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Grantham |

| Leader of the House of Commons | |

| In office 7 February 1806 – 13 September 1806 |

|

| Prime Minister | William Grenville |

| Preceded by | William Pitt the Younger |

| Succeeded by | Viscount Howick |

| In office 27 March 1782 – 5 July 1782 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Marquess of Rockingham |

| Preceded by | Lord North |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Townshend |

| Lord Commissioner of the Treasury | |

| In office 9 January 1773 – 18 February 1774 |

|

| Prime Minister | Lord North |

| Preceded by | Charles Jenkinson |

| Succeeded by | Viscount Beauchamp Charles Wolfran Cornwall |

| Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty | |

| In office 28 February 1770 – 20 February 1772 |

|

| Prime Minister | Lord North |

| Preceded by | Charles Townshend Sir George Yonge, Bt |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Bradshaw |

| Member of Parliament for Westminster |

|

| In office 1785–1806 |

|

| Preceded by | Parliamentary scrutiny |

| Succeeded by | Sir Alan Gardner, Bt Earl Percy |

| In office 1780–1784 |

|

| Preceded by | Viscount Malden Lord Thomas Pelham-Clinton |

| Succeeded by | Parliamentary scrutiny |

| Member of Parliament for Tain Burghs |

|

| In office 1784–1785 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles Ross |

| Succeeded by | George Ross |

| Member of Parliament for Malmesbury |

|

| In office 1774–1780 |

|

| Preceded by | Earl of Donegall Hon. Thomas Howard |

| Succeeded by | Viscount Fairford Viscount Lewisham |

| Member of Parliament for Midhurst |

|

| In office 1768–1774 |

|

| Preceded by | John Burgoyne Bamber Gascoyne |

| Succeeded by | Herbert Mackworth Clement Tudway |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 January 1749 London, England |

| Died | 13 September 1806 (aged 57) Chiswick, England |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Political party | Whig (Foxite) |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Armistead |

| Parents | |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | Hertford College, Oxford |

| Profession | Statesman, abolitionist |

| Signature |  |

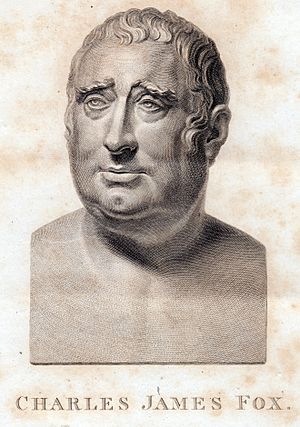

Charles James Fox (born January 24, 1749 – died September 13, 1806) was an important British politician. He was a member of the Whig party. His career in Parliament lasted for 38 years, from the late 1700s to the early 1800s. He was a big rival of the Tory politician William Pitt the Younger. Interestingly, Charles's father, Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, was also a rival of Pitt's father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham.

Fox became well-known in the House of Commons as a strong and clear speaker. At first, his ideas were quite traditional. But during the American War of Independence, his views changed. He became one of the most progressive voices in the British Parliament at that time.

Fox strongly opposed King George III, believing the King wanted too much power. He supported the American Patriots in their fight for freedom. He even wore the colors of George Washington's army. Fox served briefly as Britain's first Foreign Secretary in 1782. He returned to this role in 1783 in a special government with his old rival, Lord North. However, King George III soon removed them from power. He replaced them with the young Pitt the Younger, who was only 24. For the next 22 years, Fox was a leading voice in the opposition against Pitt's government.

Even though Fox spent most of his political life in opposition, he was known for important causes. He campaigned against slavery. He supported the French Revolution and pushed for religious tolerance and individual freedom in Parliament. His support for France during the French Revolutionary Wars caused problems with his friend and mentor, Edmund Burke. But Fox continued to fight against Pitt's wartime laws. He defended the rights of religious minorities and political activists. After Pitt died in 1806, Fox served again as Foreign Secretary. He was part of the 'Ministry of All the Talents' led by William Grenville. Fox died later that year, at age 57.

Contents

Charles Fox's Early Life (1749–1768)

Charles Fox was born in London on January 24, 1749. He was the second son of Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, and Lady Caroline Lennox. His father, Henry Fox, was a wealthy politician. He was known for being very fond of Charles. People said Charles was his father's favorite.

Stories about Charles's childhood show how much his father spoiled him. Once, Charles wanted to break his father's watch. His father let him smash it without punishment. Another time, his father had a wall rebuilt and torn down again just so Charles could watch.

Charles chose his own education. In 1758, he went to a school in Wandsworth. Then he attended Eton College, where he developed a love for classical literature. He always carried a copy of the Roman poet Horace with him later in life. His father took him out of school in 1761 to see the coronation of King George III. He also traveled to Europe in 1763, visiting Paris and Spa. During this trip, his father encouraged him to gamble. Fox returned to Eton later that year. He was known for his love of gambling and foreign fashions.

Fox started at Hertford College, Oxford, in 1764. But he left without finishing his degree. He found the college "nonsenses." He traveled more in Europe. He met important people like Voltaire and Edward Gibbon in Paris.

Early Political Career (1768–1774)

Becoming a Member of Parliament

In 1768, Charles Fox's father bought him a seat in Parliament. This was for the Midhurst area. Charles was only nineteen, which was technically too young to be an MP. Between 1768 and 1774, Fox spoke in the House of Commons over 250 times. He quickly became known as a brilliant speaker.

At first, Fox supported the government. He helped in the effort to punish John Wilkes, a radical who challenged Parliament. Because of this, Fox and his brother were sometimes insulted by crowds in London who supported Wilkes.

Between 1770 and 1774, Fox's early career faced some challenges. He was appointed to the Board of Admiralty in 1770. But he resigned because he opposed the government's Royal Marriages Act. In 1772, he was appointed to the board of the Treasury. He resigned again in 1774. These actions showed that he didn't take government jobs lightly. King George III noticed this and thought Fox wasn't serious.

After 1774, Fox started to change his political views. He was influenced by Edmund Burke, who became his mentor. The events of the American Revolution also shaped his opinions. He began to align with the Rockingham Whig party.

During this time, Fox became a strong critic of Lord North. He also criticized how the American War was being handled.

Supporting the American Revolution

Fox believed that Britain could not win against the American colonies. He saw the American fight as a struggle for freedom against unfair policies. He even corresponded with Thomas Jefferson and met Benjamin Franklin. Fox and his supporters started wearing buff and blue. These were the colors of Washington's army uniforms.

Fox strongly disliked King George III. He thought the King wanted to take too much power from Parliament. The King, in turn, deeply disliked Fox. He saw Fox as untrustworthy and someone who didn't take things seriously. On April 6, 1780, a motion passed in the Commons. It stated that the King's power had grown too much and should be reduced.

Fox was not in Parliament for the start of this debate. He was leading a large public meeting in Westminster Hall. The meeting supported "Annual Parliaments and Equal Representation." This period showed Fox becoming more radical. He was embraced by the reform movement. When the Gordon riots happened in London in 1780, Fox disliked the violence. But he said he would rather be ruled by a crowd than a standing army. In July, Fox was elected to represent Westminster. This was a large and important area. He earned the nickname "Man of the People."

Later Political Career (1782–1797)

Government Changes

Lord North resigned in March 1782 after Britain lost the American War. The Marquess of Rockingham formed a new government. Fox was made Foreign Secretary. Rockingham recognized the independence of the American colonies. But he died unexpectedly in July. Fox refused to serve in the next government. This split the Whig party.

Fox then found himself working with his old enemy, Lord North. They formed a special government called the Fox-North Coalition in April 1783. King George III did not want this government. It was the first time he had no say in who held government office. Fox returned to his role as Foreign Secretary. The King even considered stepping down. He disliked Fox and North being forced upon him.

The coalition government did not last long. The Treaty of Paris was signed in September 1783. This officially ended the American Revolutionary War. Fox then proposed a bill about the British East India Company. This company controlled a large part of India. Fox wanted to put the company under Parliament's control. The bill passed in the Commons. But the King told the Lords not to vote for it. So, the Lords rejected the bill.

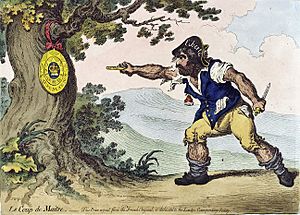

King George III now felt he could dismiss Fox and North. He appointed William Pitt as Prime Minister. Pitt was only 24 years old. Fox used his power in Parliament to oppose Pitt. But in March 1784, the King dissolved Parliament. In the next election, Pitt won with a large majority.

In Fox's own area of Westminster, the election was very competitive. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, helped campaign for him. Fox won by a very small number of votes. Legal challenges delayed the final result for over a year. During this time, Fox served as an MP for a Scottish area called Tain or Northern Burghs.

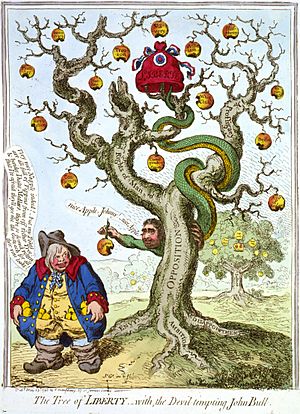

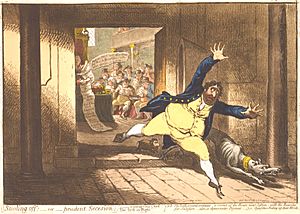

These years were important for Fox. He believed King George III was trying to control Parliament too much. Pitt seemed to Fox like a tool of the King. However, the King and Pitt had a lot of public support. Many people saw Fox as a troublemaker. He was often shown in cartoons as a villain.

In Opposition

One of Pitt's first big actions as Prime Minister was to suggest changes to Parliament in 1785. He wanted to make the electoral system fairer. Fox supported Pitt's ideas, even though it wasn't politically easy. But the reforms were defeated. Parliament would not seriously consider reform for another ten years.

In 1787, a major political event happened. This was the Impeachment of Warren Hastings. Hastings was the Governor of Bengal. He was accused of corruption. Fox was one of the people managing the trial. He was enthusiastic at first. If the trial showed problems with the British East India Company, it would prove Fox's earlier ideas were right. The trial lasted a long time, until 1795. Fox's interest faded, and Edmund Burke took on most of the work.

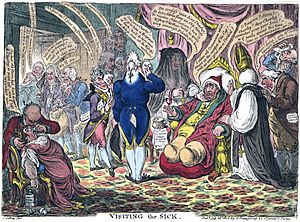

The Regency Crisis

In late 1788, King George III became mentally ill. He said Pitt was "a rascal" and Fox was "his friend." This created a chance for Fox's friend, the Prince of Wales, to become regent. A regent would rule in place of the King. This would allow Fox to form a new government.

However, Fox was in Italy when the crisis began. He returned to Britain in November 1788. He then became very ill himself. He didn't fully recover until December 1789.

When Fox finally spoke in Parliament, he seemed to make a mistake. He said that the Prince of Wales had the right to become regent immediately. Pitt strongly disagreed. He argued that Parliament had the right to decide who the monarch should be. Fox believed the King's illness was permanent. He thought challenging the Prince's right would go against basic property rights. Pitt, however, hoped the King's madness was temporary.

While Fox planned his new government, Pitt delayed the process. He created debates about the rules for a regency. He also worked on a Regency Bill. This bill would limit the Prince of Wales's powers as regent. The bill passed the Commons in February. But then, the King's health improved. Parliament decided to stop further action. The King recovered, preventing his son from becoming regent and Fox from becoming Prime Minister. Fox's chance was gone.

The French Revolution and its Impact

Fox welcomed the French Revolution in 1789. He saw it as a European version of Britain's own Glorious Revolution of 1688. After the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, he famously said it was "the greatest event... and how much the best!" In 1791, Fox praised France's new constitution. He called it "the most stupendous and glorious edifice of liberty." He was surprised by his friend Edmund Burke's reaction. Burke warned that the revolution was violent and would lead to chaos. Fox thought Burke's book was "in very bad taste."

Fox then focused on repealing the Test and Corporation Acts. These laws limited the freedoms of Protestants who were not Anglicans and Catholics. On March 2, 1790, Fox gave a powerful speech. Burke, fearing the changes in France, sided with Pitt. He called Nonconformists "dangerous." Fox replied that Burke's change in principles filled him with "grief and shame." Fox's motion was defeated.

Later, Fox successfully supported the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791. This law expanded the rights of British Catholics.

In 1791, war was more likely with Spain and Russia than with France. Fox opposed Pitt's aggressive stance in these conflicts. Fox helped resolve these issues peacefully. He gained an admirer in Catherine the Great of Russia. On April 18, Fox spoke in favor of ending the slave trade. William Wilberforce, Pitt, and Burke also supported this. But the vote went against them.

On May 6, 1791, Fox and Burke had a tearful argument in Parliament. Their 25-year friendship ended. Burke moved to sit with Pitt, taking many conservative Whigs with him. This happened during a debate about governing Canada. Later, on his deathbed, Burke refused to see Fox for a final reconciliation.

Challenging "Pitt's Terror"

Fox continued to defend the French Revolution. He believed the old monarchies were a greater threat to freedom than the new French government. He argued that European rulers attacking France had forced the revolutionaries to take extreme measures. Fox was not surprised when Britain joined the war. He blamed Pitt and the King for the long French Revolutionary Wars.

Many in Britain saw Fox as a traitor. But in France, he was on a list of Britons to be transported if France invaded Britain. This was because he had "insulted the French nation" in his speeches. Some people even believed Fox was secretly paid by France.

Fox's radical views became too extreme for many of his followers. Friends like the Duke of Portland joined the government side. After these defections, Fox's group in Parliament became very small. They were reduced to about fifty MPs.

Fox still challenged the strict wartime laws Pitt introduced in the 1790s. These laws were called "Pitt's Terror." In 1792, Fox passed the only major law of his career, the Libel Act 1792. This law gave juries the right to decide what was libelous. This was a big step for common people's rights. However, more libel cases were brought by the government after this act.

Fox spoke against the King's speech in December 1793. He was defeated in the vote. He argued against war measures. These included bringing German troops to Britain and suspending habeas corpus in 1794. Habeas corpus is a law that protects people from being held without trial.

In 1795, the King's carriage was attacked. This led Pitt to introduce two harsh laws: the Seditious Meetings Act 1795 and the Treasonable Practices Act. The first law banned unlicensed gatherings of over fifty people. The second law made the definition of treason much wider. Fox spoke many times against these acts. He argued that public meetings were important for people to watch over Parliament.

Parliament passed the acts. But Fox gained support outside of Parliament. Many people signed petitions for him. He spoke at a public meeting of thousands of people in November 1795. However, this didn't change things in the long run. Fox's followers became frustrated with Parliament. They felt it didn't represent the people.

Later Years and Achievements (1797–1806)

Time Away from Parliament

By 1797, most people supported Pitt's war against France. Fox's group in Parliament had shrunk to about 25 MPs. Many of his followers left Parliament. Fox himself spent long periods at his wife's house in Surrey. He found peace away from Westminster. He still believed he was right to oppose the war. He said, "It is a great comfort to me to reflect how steadily I have opposed this war."

In 1798, Fox proposed a toast to "Our Sovereign, the Majesty of the People." This idea meant that the people were the true rulers. Because of this, Pitt removed Fox from the Privy Council. Fox believed this idea was essential to the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

After Pitt resigned in 1801, Fox slowly returned to politics. He opposed the new government. He joined a group that supported Catholic emancipation.

During the French Revolutionary Wars, Fox supported the French Republic. He believed Napoleon sincerely wanted peace. In 1801, a peace agreement between Britain and France was announced. Fox was very happy. He said he was glad Britain had not achieved its war goals. He even admitted he was happy about France's triumph over Britain.

After the Treaty of Amiens was signed in 1802, Fox visited France. He met Napoleon three times. Fox tried to convince Napoleon about freedom of the press. He also searched French archives for his planned history book. He wanted to write about the reign of James II and the Glorious Revolution. He left the book unfinished when he died. It was published in 1808 as A History of the Early Part of the Reign of James II.

Fox believed Napoleon wanted peace. But when war broke out again in 1803, Fox blamed the British Prime Minister. He thought Britain had forced Napoleon into war. When Napoleon won major battles in 1805, Fox was not surprised.

Final Year and Abolition of Slavery

When Pitt died in January 1806, Fox was the last major political figure left. He could no longer be kept out of government. William Grenville formed a new government. Fox was offered the job of Foreign Secretary again, and he accepted. Fox believed France wanted lasting peace. He quickly started peace talks with Talleyrand, the French foreign minister. However, by July, Fox realized he was wrong about Napoleon's peaceful intentions. Negotiations failed.

These failed talks were a "stunning experience" for Fox. He had always insisted that France wanted peace. Now, he saw that this was not true. Some observers felt Fox had changed his views too much.

Even though the government didn't achieve peace or Catholic emancipation, Fox had one last great success. This was the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Fox died before the act was fully passed. But he oversaw a bill in 1806 that stopped British people from trading slaves with Britain's enemies. This cut two-thirds of the slave trade through British ports.

On June 10, 1806, Fox proposed a resolution to Parliament. He said the African slave trade was against justice, humanity, and good policy. He called for measures to abolish it. The House of Commons voted 114 to 15 in favor. The Lords approved the motion on June 24.

Death and Legacy

Fox died in office at Chiswick House on September 13, 1806. This was less than eight months after Pitt died. Fox had some debts when he died. His funeral was held at Westminster Abbey on October 10, 1806. This was the anniversary of his first election for Westminster. Unlike Pitt's funeral, Fox's was private. But many people still came to pay their respects.

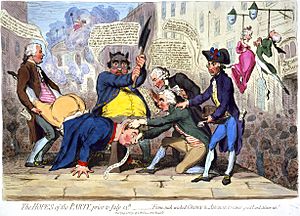

Fox's Personal Side

Fox was known for his love of horse riding and cricket. He was also known for his strong eyebrows, which earned him the nickname 'the Eyebrow' among his friends. He was often made fun of in cartoons, especially by James Gillray. Fox found these cartoons amusing and kept a collection of them. He didn't seem bothered by criticism.

Fox married Elizabeth Armistead in 1795. He kept their marriage private until 1802. Elizabeth was never fully accepted at court. Fox spent more time away from Parliament at their home, St. Ann's Hill, in Surrey. There, Elizabeth helped him calm his wilder habits. They would read, garden, and entertain friends. Elizabeth outlived him by 36 years.

Despite his flaws, Fox was seen as a friendly person. His friend George Selwyn said Fox was "agreeable." Edward Gibbon said Fox was free from "malevolence, vanity, or falsehood." For Fox, friendship was the most important thing. He wasn't very interested in the details of policy, especially economics. His political allies were also his close friends.

Fox's Lasting Impact

In the 1800s, liberals saw Fox as a hero. They praised his bravery, determination, and speaking skills. They admired his opposition to war and his fight for freedoms at home. They celebrated his efforts for parliamentary reform, Catholic Emancipation, and ending the slave trade. Modern historians study Fox in the context of his time. They highlight his brilliant debates with Pitt. A statue of Fox stands in St Stephen's Hall in the Palace of Westminster.

While not as famous today as Pitt, Fox's influence was significant. After 1794, people started using "Foxite" to describe those who opposed Pitt. The rivalry between Pitt and Fox helped create the Conservative and Liberal parties of the 1800s. Their political and speaking skills were legendary. Even Pitt recognized Fox's talent.

The Fox Club was founded in London in 1790. It held annual dinners celebrating Fox's birthday. Fox's name was often used in debates by those supporting Catholic Emancipation and the Great Reform Act in the early 1800s. Many Whig households collected items related to Fox, like busts and copies of his speeches.

The town of Foxborough, Massachusetts, in the United States, was named after him. This was to honor his strong support for American independence. In his hometown of Chertsey, a bust of Fox was put up in 2006. His college, Hertford College, Oxford, also holds a dinner in his honor.

Fox was featured in John F. Kennedy's book Profiles in Courage. Kennedy used a quote from Edmund Burke praising Fox's courage in challenging power.

Fox has been played by many actors in films and TV shows:

- Robert Morley in The Young Mr. Pitt (1942)

- Leslie Banks in Mrs. Fitzherbert (1947)

- Peter Bull in Beau Brummell (1954)

- Ronald Lacey in The Fight Against Slavery (1975)

- Keith Barron in Prince Regent (1979)

- Jim Carter in The Madness of King George (1994)

- Hugh Sachs in "Aristocrats" (1999)

- Michael Gambon in Amazing Grace (2006)

- Simon McBurney in The Duchess (2008)

- Blake Ritson in Garrow's Law (2011)

See also

In Spanish: Charles James Fox para niños

In Spanish: Charles James Fox para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |