Edmund Burke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edmund Burke

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Joshua Reynolds, c. 1769

|

|

| Rector of the University of Glasgow | |

| In office 1783–1785 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry Dundas |

| Succeeded by | Robert Bontine |

| Paymaster of the Forces | |

| In office 16 April 1783 – 8 January 1784 |

|

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Isaac Barré |

| Succeeded by | William Grenville |

| In office 10 April 1782 – 1 August 1782 |

|

| Prime Minister | The Marquess of Rockingham |

| Preceded by | Richard Rigby |

| Succeeded by | Isaac Barré |

| Member of Parliament for Malton |

|

| In office 18 October 1780 – 20 June 1794 Serving with

|

|

| Preceded by | Savile Finch |

| Succeeded by | Richard Burke Jr. |

| Member of Parliament for Bristol |

|

| In office 4 November 1774 – 6 September 1780 Serving with Henry Cruger

|

|

| Preceded by | Matthew Brickdale |

| Succeeded by | Henry Lippincott |

| Member of Parliament for Wendover |

|

| In office December 1765 – 5 October 1774 Serving with

|

|

| Preceded by | Verney Lovett |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 January 1729 Dublin, Leinster, Kingdom of Ireland |

| Died | 9 July 1797 (aged 68) Beaconsfield, England, Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Political party | Whig (Rockinghamite) |

| Spouse |

Jane Mary Nugent

(m. 1757) |

| Children | Richard Burke Jr. |

| Education | Trinity College Dublin Middle Temple |

| Occupation | Writer, politician, journalist, philosopher |

|

Philosophy career |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Conservatism Liberalism Counter-Enlightenment |

| Institutions | Literary Club (co-founder) |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

| Signature | |

Edmund Burke (born January 12, 1729 – died July 9, 1797) was an important Anglo-Irish statesman, economist, and philosopher. He was born in Dublin, Ireland. Burke served as a member of Parliament (MP) from 1766 to 1794. He was part of the Whig Party in the House of Commons of Great Britain.

Burke believed that good manners and strong religious groups were important for a stable and healthy society. He wrote about these ideas in his book A Vindication of Natural Society. He also spoke out against how the British government treated the American colonies, especially their tax rules. Burke supported the colonists' right to protest, but he did not want them to become fully independent. He is also known for supporting Catholic emancipation (giving Catholics more rights). He worked to remove Warren Hastings from the East India Company. Burke was also strongly against the French Revolution.

In his book Reflections on the Revolution in France, Burke argued that the French Revolution was destroying good society and old traditions. He also criticized how the Catholic Church was treated during the revolution. This made him a leader of the conservative part of the Whig Party. He called them the "Old Whigs," to show they were different from the "New Whigs" who supported the French Revolution.

Later, in the 19th century, both conservatives and liberals admired Burke. In the 20th century, especially in the United States, he became known as the person who started the ideas of conservatism.

Contents

Edmund Burke's Early Life

Edmund Burke was born in Dublin, Ireland. His mother, Mary, was a Roman Catholic. His father, Richard, was a successful lawyer and a member of the Church of Ireland. Burke followed his father's faith and was an Anglican his whole life. However, his sister Juliana was raised Catholic. Later, his political rivals often accused him of being secretly Catholic. At that time, Catholics were not allowed to hold public office in Ireland.

As a child, Burke sometimes stayed with his mother's family in County Cork. He went to a Quaker school in Ballitore, County Kildare. He kept in touch with his schoolmate, Mary Leadbeater, throughout his life.

In 1744, Burke started studying at Trinity College Dublin. This was a Protestant establishment that did not allow Catholics to get degrees until 1793. In 1747, he started a debating club. This club later joined with another to form the College Historical Society, which is the oldest student society in the world. Burke finished his degree in 1748.

Burke's father wanted him to study law. So, in 1750, Burke went to London and joined the Middle Temple. But he soon stopped studying law. Instead, he traveled in Continental Europe and started a career as a writer.

Becoming a Writer and Thinker

In 1756, Burke published his first major work, A Vindication of Natural Society: A View of the Miseries and Evils Arising to Mankind. In this book, Burke used irony to show problems with some popular ideas of his time. Many people first thought the book was serious, not a satire. Burke had to explain in a later edition that it was meant to be funny and thought-provoking.

In 1757, Burke wrote a book about aesthetics called A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. This book got attention from famous thinkers like Denis Diderot and Immanuel Kant. It was his only book purely about philosophy.

Burke also signed a contract to write a "history of England." He finished part of it, but it was not published until after he died. In the same year, Burke helped start the Annual Register. This was a publication where writers reviewed the important political events of the past year. Burke was the main editor for many years.

On March 12, 1757, Burke married Jane Mary Nugent. Their son, Richard, was born in 1758. Burke also helped raise his nephew, Edmund Nagle, who later became an Admiral.

Around this time, Burke met William Gerard Hamilton. Burke became his private secretary when Hamilton became Chief Secretary for Ireland. In 1765, Burke became private secretary to Charles, Marquess of Rockingham. Rockingham was then the Prime Minister of Great Britain. They remained close friends until Rockingham's death in 1782.

A Voice in Parliament

In December 1765, Burke became a Member of Parliament (MP) for Wendover. This was a "pocket borough," meaning a small area where one person (in this case, Lord Fermanagh, a friend of Rockingham) largely controlled who got elected. After Burke's first speech, William Pitt the Elder praised him greatly.

One of the first big issues Burke spoke about was the conflict with the American colonies. This conflict later led to the American Revolutionary War. Burke published a pamphlet called Observations on a Late State of the Nation. In it, he looked at France's money problems and predicted a big change there.

Around this time, Burke bought a large estate called Gregories near Beaconsfield. It was a big financial challenge for him. His speeches and writings made him famous. He also joined a group of important thinkers and artists in London, including Samuel Johnson, David Garrick, and Joshua Reynolds.

Burke played a key role in debates about the king's power. He argued strongly against the king having too much power. He believed political parties were important to stop abuses of power by the king or by certain groups in the government. His important writing on this was Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770). He said that "secret influence" from the king's friends was causing problems. He believed Britain needed a party that stuck to its principles.

In 1771, Burke tried to pass a law that would give juries the right to decide what was libel (false statements that harm someone's reputation). He also helped make it possible to publish debates held in Parliament.

Burke believed in a free market for goods like corn. In 1770, he argued that there was only a "natural price" for grain. In 1772, he helped pass a law that removed old rules against corn dealers.

In 1773, Burke spoke out against the division of Poland. He saw it as a big problem for the balance of power in Europe.

In 1774, Burke was elected MP for Bristol. This was a large city and a real election contest. He gave a famous speech where he explained that an MP should use their own judgment, not just do what their voters demand. He lost re-election for Bristol in 1780.

Burke also supported changes to rules that limited Irish trade. His voters in Bristol, a big trading city, wanted him to oppose free trade with Ireland. But Burke stood firm. He said that if he lost their votes, it would show future MPs that someone dared to do what he thought was right, even if it was unpopular.

He also supported efforts to remove some of the harsh laws against Catholics. Burke even called capital punishment "the Butchery which we call justice" in 1776.

Because he supported these unpopular ideas, like free trade with Ireland and rights for Catholics, Burke lost his seat in 1780. For the rest of his time in Parliament, he represented Malton. This was another "pocket borough" where the Marquess of Rockingham had influence.

Standing Up for America

Burke supported the complaints of the American Thirteen Colonies against King George III's government.

On March 22, 1775, Burke gave a speech in Parliament about making peace with America. He argued for peace instead of war. He reminded Parliament about America's growing population, its hard work, and its wealth.

Burke gave four main reasons why Britain should not use force against the colonies:

- First, force would only be a temporary solution. The colonists' desire for freedom would not go away.

- Second, it was not certain that Britain would win a war in America. "An armament," Burke said, "is not a victory."

- Third, using force would damage America. It would do no good to win a war if the land and people were ruined.

- Fourth, Britain had no experience in controlling a colony by force from so far away.

Burke said the most important reason to avoid war was the character of the American people themselves. He described them as having a strong "love of freedom." He said they were "acute, inquisitive, dextrous, prompt in attack, ready in defence, full of resources." Burke ended his speech with a plea for peace. He prayed that Britain would avoid actions that could "bring on the destruction of this Empire."

Burke suggested six ways to solve the American conflict peacefully:

- Let the American colonists elect their own representatives to deal with taxes.

- Admit that Britain had made mistakes and apologize.

- Find a good way to choose and send these representatives.

- Set up a General Assembly in America to handle taxes.

- Stop collecting taxes by force and only collect them when needed.

- Give the colonies the help they required.

These ideas were not put into action. Just before the battles at Concord and Lexington, Burke gave this speech. The conflict soon exploded.

Burke was upset by celebrations in Britain when Americans were defeated in New York and Pennsylvania. He felt that this harsh approach was changing the English character. He believed the British government was fighting "our English Brethren in the Colonies" with a German king using "German boors and vassals" to destroy English liberties. When America became independent, Burke said he didn't want success for those who would separate from the Empire. But he also didn't want success for "injustice, oppression and absurdity."

During the Gordon Riots in 1780, Burke was targeted. His home had to be protected by soldiers.

Working in Government

When the government changed in March 1782, Rockingham became Prime Minister again. Burke was made Paymaster of the Forces and a Privy Counsellor. This meant he advised the King. Rockingham died unexpectedly in July 1782, and the government changed again.

But Burke managed to introduce two important laws:

- The Paymaster General Act 1782 stopped the Paymaster job from being a way to make easy money. Before, Paymasters could take money from the Treasury as they pleased. Now, they had to put the money in the Bank of England and only take it out for specific reasons.

- The Civil List and Secret Service Money Act 1782 cut down on royal household and government offices. It abolished 134 positions and limited pensions. This was expected to save a lot of money each year.

In February 1783, Burke became Paymaster of the Forces again for a short time. After that government fell, William Pitt the Younger became Prime Minister. Burke was then in the opposition for the rest of his political career.

What is Representative Democracy?

Burke was a bit unsure about full democracy. He thought that while it might sound good, it could be ineffective or even unfair in Britain at the time. He had three main reasons:

- First, he believed government needed smart people with a lot of knowledge, which he thought was rare among common people.

- Second, he worried that ordinary people could be easily swayed by powerful speakers, leading to anger and violence. This could harm traditions and religion.

- Third, Burke warned that democracy could lead to a "tyranny of the majority," where unpopular groups would not be protected.

Fighting Against Slavery

Burke was against the slave trade. He suggested a law to stop slave owners from being members of Parliament. He believed they were a danger to British freedom. While Burke thought that African people needed to be "civilised" by Christianity, he also believed that slavery itself made people less virtuous. He proposed a plan for gradually freeing slaves. This plan was very detailed for its time.

Helping India

For many years, Burke worked to remove Warren Hastings, who was the Governor-General of Bengal in India. Burke believed Hastings had done wrong things. This effort led to a long trial starting in 1786.

Burke became very involved in issues with the East India Company in India. He was appointed head of a committee to investigate problems in Bengal. Burke wrote reports that told Indian princes that Britain would not wage war on them. He also demanded that the East India Company remove Hastings. This was Burke's first big call for changes in how the British Empire acted.

In 1785, Burke gave a famous speech called The Nabob of Arcot's Debts. In it, he strongly criticized the harm done to India by the East India Company. He argued that the Company's rule had damaged good Indian traditions and caused suffering. He wanted to set up clear moral rules for how an overseas empire should be run.

On April 4, 1786, Burke formally accused Hastings of "High Crimes and Misdemeanors" in Parliament. The trial began in 1788 and became a very public event. Burke was known for his powerful speeches. He called Hastings a "captain-general of iniquity" and a "spider of Hell." The House of Commons eventually accused Hastings, but the House of Lords later found him not guilty of all charges.

Views on the French Revolution

At first, Burke did not completely condemn the French Revolution. In August 1789, he wrote that he was amazed by France's fight for liberty. But he also noted that the "old Parisian ferocity" had appeared in a shocking way. The events of October 5-6, 1789, when Parisian women marched on Versailles and forced King Louis XVI to return to Paris, changed Burke's mind. He then described France as "a country undone."

In January 1790, Burke read a sermon by Richard Price that praised the French Revolution. Price argued that the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England gave people the right to choose and remove their leaders.

Burke disagreed strongly with Price. He immediately started writing what became Reflections on the Revolution in France. He published it on November 1, 1790. It became a best-seller right away, selling thousands of copies. A French translation also became very popular.

In Reflections, Burke argued against Price's view of the Glorious Revolution. Burke believed that society was a partnership not just between living people, but also with those who had died and those yet to be born. He said that people should respect traditions and institutions because they are based on the wisdom of many generations. He criticized the French Revolution for trying to completely rebuild society based on new, untested ideas.

One famous part of Burke's Reflections described the events of October 1789 and the role of Marie Antoinette. Burke's dramatic language about the queen caused both praise and criticism.

Many of Burke's fellow Whig MPs, like Richard Sheridan and Charles James Fox, disagreed with him. This led to a split in the Whig Party and ended Burke's friendship with Fox. Fox thought Burke's Reflections were "in very bad taste." However, other Whigs, like the Duke of Portland, privately agreed with Burke.

Burke wanted to show that he was still true to Whig principles. He published An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs in 1791. In this book, he again criticized the radical ideas of the French Revolution. He argued that Whigs who supported these ideas were going against the party's traditional beliefs.

Eventually, most Whigs sided with Burke. They supported William Pitt the Younger's government, which declared war on Revolutionary France in 1793.

Burke supported the war against France. He saw it as a fight against a dangerous new way of thinking, not just against the French nation. He even revealed a dagger in Parliament, saying it showed what Britain would gain from an alliance with France.

In 1794, Burke received thanks from Parliament for his work in the Hastings Trial. He then resigned his seat in Parliament. Sadly, his son Richard died shortly after, which was a huge loss for Burke. King George III offered to make him a lord, but Burke only accepted a pension. When some people criticized this pension, Burke replied in his Letter to a Noble Lord (1796). He argued that his reward was based on his hard work, unlike those who inherited their wealth. He famously wrote: "To innovate is not to reform."

Burke's last writings were the Letters on a Regicide Peace (1796). In these, he argued against making peace with France. He believed the war was about ideas, against an "armed doctrine." He saw the French Revolution as a dangerous movement trying to take over all of Europe.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Burke continued to write about important issues. In 1795, he wrote about the high price of corn. He believed in the ideas of Adam Smith, who thought that markets should be free. Smith himself said that Burke was the only person he knew who thought about economics exactly like him.

Burke died in Beaconsfield, England, on July 9, 1797. He was buried there next to his son and brother.

Most political historians see Burke as a liberal conservative. He is often called the father of modern British conservatism. Burke believed that owning property was very important for society. He thought that the way property was divided helped create social order and control.

Burke's support for groups like Irish Catholics and Indians, who were often treated unfairly, sometimes made him unpopular with some politicians. But his strong opposition to the French Revolution also made him unpopular with others. This meant Burke was often alone in Parliament.

In the 19th century, both liberals and conservatives praised Burke. Even his political opponents, like William Hazlitt, admired him. Many important figures, including William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who first criticized Burke, later came to admire his ideas and predictions. George Canning, a Prime Minister, said Burke's Reflections had been proven right by later events.

The Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was greatly influenced by Burke's later writings. The Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone called Burke "a magazine of wisdom on Ireland and America."

Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France was debated when it came out. But after his death, it became his most famous and important work. It is seen as a key text for conservative thinking.

Historians like Piers Brendon say that Burke helped set the moral rules for the British Empire. Burke believed that the British Empire "must be governed on a plan of freedom." This idea, that colonial government should benefit the people it ruled, was very important.

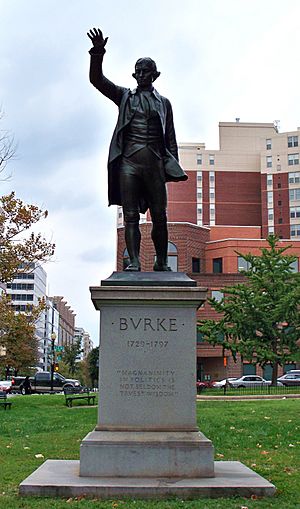

There are statues of Burke in Bristol, England, Trinity College Dublin, and Washington, D.C.. A school in Washington, D.C., and a street in New York are also named after him.

Religious Beliefs

Burke believed that religion was the foundation of civil society. He strongly criticized deism (belief in a distant God) and atheism (no belief in God). He emphasized that Christianity helped society progress. Even though his mother was Catholic and his father Protestant, Burke strongly defended the Church of England. He also understood and cared about Catholic issues. He believed that having a state-supported religion helped protect people's freedoms. He thought Christianity benefited not only a person's soul but also how society was organized.

Famous Sayings

The quote "The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing" is often said to be from Burke. However, it is not certain if he actually said or wrote these exact words.

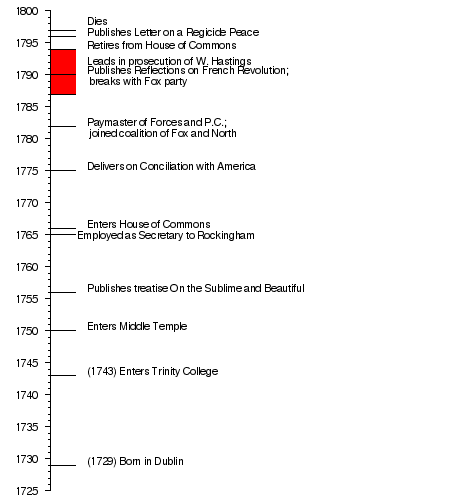

Timeline

In Popular Culture

Actor T. P. McKenna played Edmund Burke in the TV series Longitude in 2000.

See also

In Spanish: Edmund Burke para niños

In Spanish: Edmund Burke para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |