Samuel Johnson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Johnson

|

|

|---|---|

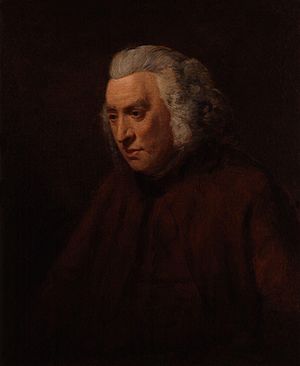

Portrait by Joshua Reynolds, c. 1772

|

|

| Born | 18 September 1709 (OS 7 September) Lichfield, England

|

| Died | 13 December 1784 (aged 75) London, England

|

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Education | Pembroke College, Oxford |

| Political party | Tory |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Writing career | |

| Pen name | Dr Johnson |

| Language | English |

| Notable works | |

| Signature | |

|

|

Samuel Johnson (born September 18, 1709 – died December 13, 1784), often called Dr. Johnson, was a very important English writer. He was a poet, a playwright, an essay writer, a critic, a biographer, and he even created a dictionary! Many people think he was one of the most distinguished writers in English history.

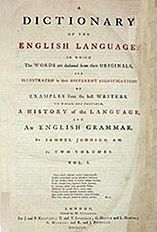

Samuel Johnson was born in Lichfield, England. He went to Pembroke College, Oxford, but had to leave because he ran out of money. After teaching for a while, he moved to London and started writing for The Gentleman's Magazine. One of his biggest achievements was his A Dictionary of the English Language, which took him nine years to finish and was published in 1755. It was praised as a huge success in scholarship. Later, he wrote essays, edited William Shakespeare's plays, and wrote a story called The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia. In 1763, he became friends with James Boswell, who later wrote a famous book about Johnson's life. Johnson also wrote about his travels to Scotland in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland. Towards the end of his life, he wrote an important work called Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets.

Johnson was a very religious man and a strong supporter of the Tory political party. He was tall and had some unusual movements and habits that surprised people. His friend Boswell wrote down many details about Johnson's behavior. These descriptions have led some modern doctors to believe he might have had Tourette syndrome, a condition that wasn't known back then. After several illnesses, Samuel Johnson died on December 13, 1784, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

After his death, Johnson became even more famous. People realized how much he had influenced literary criticism and biography. His Dictionary had a huge impact on the English language and was the most important dictionary for 150 years, until the Oxford English Dictionary came along. James Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson is considered one of the most famous biographies ever written.

Contents

Samuel Johnson: A Famous Writer

His Early Life and School Days

Samuel Johnson was born on September 18, 1709. His parents were Sarah and Michael Johnson, who was a bookseller. His mother was 40 years old when he was born, which was quite late for that time. They were worried about his health because he didn't cry when he was born. A vicar was called to baptize him right away.

When Samuel was a baby, he got a disease called scrofula. People back then thought that royalty could cure it, so young Johnson was touched by Queen Anne in 1712. However, it didn't work, and he had an operation that left scars on his face and body.

Samuel was a very smart child. His parents started his education when he was three, teaching him from the Book of Common Prayer. He went to different schools, and by age seven, he was at Lichfield Grammar School. He was very good at Latin. Around this time, he started having the unusual movements that people noticed throughout his life. These movements are now thought to be signs of Tourette syndrome. He did very well in school and made lifelong friends like John Taylor.

When he was 16, Johnson stayed with his cousins, who helped him with his studies. He then went to King Edward VI grammar school for six months. After that, he returned home, and his future was uncertain because his father was in debt. Samuel helped his father by stitching books and spent a lot of time reading in his father's bookshop.

Facing Challenges as a Young Man

In 1728, when Johnson was 19, his mother's cousin died and left them some money. This allowed him to go to Pembroke College, Oxford. He made friends there and read many books. He even translated half of Alexander Pope's poem Messiah into Latin in one afternoon. This poem was later published and was his first known work.

However, the money didn't last, and Johnson had to leave Oxford after 13 months without getting a degree. He was deeply in debt. He hoped to return, but he never did to study. Years later, in 1755, the University of Oxford gave him an honorary Master of Arts degree because of his famous Dictionary. He also received honorary doctorates from other universities.

After leaving Oxford, Johnson faced hard times. His father died in 1731, leaving the family in even more debt. Johnson tried to get a teaching job but was turned down because he didn't have a degree. He eventually found work as an assistant teacher at a school in Market Bosworth. He found teaching boring and was treated poorly, so he left after a short time.

In 1734, Johnson helped a publisher named Thomas Warren with his Birmingham Journal. He also translated a book called A Voyage to Abyssinia. Around this time, his friend Harry Porter died. Johnson then started to spend time with Porter's wife, Elizabeth, who was 45 and had three children. Johnson was 25. They married on July 9, 1735. Elizabeth's family didn't approve because of the age difference, but her daughter Lucy accepted Johnson.

In 1735, Johnson tried to open his own school, Edial Hall School, near Lichfield. He only had three students, including the famous actor David Garrick. The school was not successful and cost his wife a lot of her savings. It's thought that Johnson's unusual movements, possibly from Tourette syndrome, made it hard for him to be a schoolmaster. This might have led him to focus on writing instead.

In 1737, Johnson moved to London with David Garrick. He was very poor. He started working for The Gentleman's Magazine, writing many different kinds of articles. In 1738, his first major poem, London, was published anonymously. It described the problems of London, like crime and poverty.

Johnson became friends with the poet Richard Savage. They were both very poor and sometimes had to sleep on the streets. They worked as "Grub Street writers," meaning they wrote anonymously for publishers for quick money. Savage died in 1743, and Johnson wrote a biography about him called Life of Mr Richard Savage (1744). This book was very important in the history of biographies.

Creating the First English Dictionary

In 1746, a group of publishers asked Johnson to create a complete dictionary of the English language. He signed a contract for 1,500 guineas (a lot of money back then) and said he could finish it in three years. For comparison, the French Academy had 40 scholars working for 40 years on their dictionary! Johnson didn't finish in three years, but he did complete it in eight.

How the Dictionary Was Made

Working on the Dictionary was a huge task. Johnson hired several assistants to help with copying and organizing. His house was full of noise and books. He would underline words in books he wanted to include, and his assistants would copy those sentences onto slips of paper. These slips were then alphabetized and used as examples for the word definitions.

Johnson's wife, Tetty, was very ill during this time. To be closer to his printer, Johnson moved to 17 Gough Square.

Before starting the Dictionary, Johnson wrote a "Plan" for it. A rich man named Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield was supposed to support the project. Seven years later, Chesterfield wrote some essays praising the Dictionary. But Johnson felt Chesterfield hadn't helped him enough when he really needed it. Johnson wrote a famous letter to Chesterfield, saying that a patron who only helps when you no longer need it is not truly helpful. Chesterfield was so impressed by the letter that he displayed it for others to read.

The Dictionary was finally published in April 1755. It was a very large book, almost 18 inches tall when closed and 20 inches wide when open. It had 42,773 words. It was expensive, costing about £4 10s, which is like £350 today. A key new idea in Johnson's dictionary was using quotes from famous writers to show how words were used. He included about 114,000 quotes from authors like William Shakespeare, John Milton, and John Dryden. It took years for the Dictionary to make a profit. Johnson didn't get any more money from sales after his initial payment.

Johnson's dictionary wasn't the first, but it was the most important for 150 years, until the Oxford English Dictionary was finished in 1928. It gave people a clear understanding of how the English language was used in the 18th century.

While working on the dictionary, Johnson also wrote many essays, sermons, and poems. In 1750, he started a series of essays called The Rambler, published twice a week. He wrote 208 essays, each about 1,200-1,500 words long. He said he chose the name The Rambler because it was the best idea he had one night. These essays often talked about moral and religious topics. They became very popular when they were collected into a book.

His poem The Vanity of Human Wishes was written very quickly. It talks about how human desires often lead to unhappiness and that true happiness comes from spiritual wishes. The poem was praised by critics but didn't sell as well as London. In 1749, his play Irene was finally performed, but it wasn't very popular.

Johnson's wife, Tetty, was sick for most of her time in London. She died on March 17, 1752. Johnson was heartbroken and felt guilty that he hadn't been able to provide for her better. He wrote many prayers and sad notes in his diary about her death. Her death made it harder for him to finish his work.

Later Years and Important Works

In 1756, Johnson was arrested because he owed £5 18s. He wrote to his friend, the publisher Samuel Richardson, who sent him money to help. Johnson also became good friends with the painter Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds's sister noticed that people would gather around Johnson and laugh at his movements. Johnson also became friends with Bennet Langton and Arthur Murphy. Around this time, a poor and blind poet named Anna Williams came to live with Johnson, and she became his housekeeper.

Johnson started working on The Literary Magazine in 1756. He wrote many reviews and essays for it. He also wrote introductions for other writers' books, like those by Charlotte Lennox. To help him at home, his friend Richard Bathurst convinced him to take on a freed slave, Francis Barber, as his servant.

Johnson spent a lot of time working on his edition of William Shakespeare's plays. In 1756, he published his plan for the Shakespeare edition, saying that earlier versions had mistakes. He was arrested again for debt in 1758, but the publisher who hired him to do the Shakespeare edition paid it off. It took him seven more years to finish the work.

In 1758, Johnson started a weekly series called The Idler to avoid finishing his Shakespeare project. These essays were shorter than The Rambler and were published in a newspaper.

Since The Idler didn't take all his time, he also wrote his famous story Rasselas in 1759. He wrote it in just one week to pay for his mother's funeral and her debts. The story is about Prince Rasselas, who lives in a perfect place called the Happy Valley. But he isn't happy there because everything is too easy. He escapes with his sister and a philosopher to see the real world, where they find that life is full of challenges. Rasselas became very popular and was translated into many languages.

Travels and Political Thoughts

By 1762, people were making fun of Johnson for taking so long to finish his Shakespeare edition. But then, King George III gave Johnson an annual pension of £300 for his work on the Dictionary. This money made him financially comfortable for the rest of his life.

On May 16, 1763, Johnson met James Boswell, who would become his main biographer. They quickly became friends, even though Boswell often traveled away from London. Around this time, Johnson started "The Club", a social group that included famous friends like Reynolds, Burke, David Garrick, and Goldsmith. They met every Monday evening.

In 1765, Johnson met Henry Thrale, a rich brewer and politician, and his wife Hester. Johnson became like a member of their family and lived with them for 17 years. Hester Thrale kept a diary that became an important source of information about Johnson's life.

Johnson's edition of Shakespeare was finally published on October 10, 1765. It sold out quickly. Johnson's new idea was to add notes that helped readers understand Shakespeare's difficult passages and correct mistakes from earlier editions.

Final Works

In 1773, Johnson traveled to Scotland with Boswell. Johnson wrote about their trip in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775). He wrote about the social problems in Scotland but also praised unique things, like a school for the deaf. Boswell also wrote about their trip in The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, which was a step towards his famous biography of Johnson.

In the 1770s, Johnson wrote several essays supporting government policies. In 1775, he wrote Taxation No Tyranny, defending the British government's right to tax the American colonies. He argued that colonists had given up their right to vote by moving to America. He also famously said, "Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel." He meant that people sometimes use "patriotism" as an excuse for bad actions, not that patriotism itself is bad.

In 1777, Johnson started his last major work, Lives of the English Poets. He was paid 200 guineas for it, which was less than he could have asked for. These "Lives" were critical studies and biographies of poets from the 17th and 18th centuries. The full collection was published in 1781.

Johnson couldn't enjoy this success for long. His dear friend Henry Thrale died in 1781. Then, his friend and tenant Robert Levet died in 1782. Johnson was very sad and became ill with bronchitis. His health was also affected by the deaths of other friends and his housekeeper, Anna Williams.

Final Years

In 1782, Johnson was upset when he learned that Hester Thrale would sell the house they shared. He was sad about losing her company. His health continued to get worse.

On June 17, 1783, Johnson had a stroke and temporarily lost his ability to speak. Doctors helped him, and he regained his speech two days later. He was also suffering from gout. His friends, including the novelist Fanny Burney, visited him often. He was confined to his room for several months.

His health improved a bit in May 1784, and he traveled to Oxford with Boswell. By July, many of his friends had died or moved away. Boswell had gone back to Scotland, and Hester Thrale was getting married. Johnson wanted to die in London and returned there in November 1784.

Many people visited Johnson as he lay sick. He died on December 13, 1784, at 7:00 p.m. His friends were very sad. William Gerard Hamilton said that Johnson had left a "chasm" that no one could fill.

Samuel Johnson was buried on December 20, 1784, in Westminster Abbey. His tombstone reads:

- Samuel Johnson, LL.D.

- Obiit XIII die Decembris,

- Anno Domini

- M.DCC.LXXXIV.

- Ætatis suœ LXXV.

His Health and Unique Habits

Johnson was tall (about 5 feet 11 inches, taller than most men back then) and strong. But his unusual movements and gestures sometimes made people think he was strange. When the artist William Hogarth first saw him, he thought Johnson was "an idiot." But then Johnson started speaking with such power that Hogarth was amazed.

Johnson had many health problems throughout his life. As a child, he had scrofula, which left scars and affected his hearing and eyesight. He also suffered from gout and later had a stroke. Doctors today believe he showed signs of Tourette syndrome, a condition that causes tics and involuntary movements. Boswell described Johnson's habits, like holding his head to one side, moving his body back and forth, and making sounds like a "half whistle" or "clucking like a hen." Johnson himself said these were "bad habits."

Despite his health challenges, Johnson achieved amazing things. A Tourette syndrome researcher called him "the most notable example of a successful adaptation to life despite the liability of Tourette syndrome."

Why Samuel Johnson is Remembered

Johnson was more than just a writer; he was a celebrity. News about his life and health was often reported in newspapers. He loved biographies and changed how they were written in the modern world. Many books and memoirs were written about him after his death, but James Boswell's Life of Johnson is the most famous.

His Impact on Writing

Johnson had a lasting influence on literary criticism. He believed that good poetry should use everyday language and avoid overly fancy or old-fashioned words. He liked poetry that was easy to understand and had new and interesting images.

In his biographies, Johnson believed in showing people accurately, including their flaws. He thought that biographies shouldn't just be about famous people, but that the lives of ordinary people were also important. He liked to include small details to fully describe his subjects.

Johnson's Dictionary was also a tool for literary criticism. He included quotes from important writers like Bacon, Milton, and Shakespeare to show how words were used in literature. He wanted readers to understand the meaning of words in context.

When he wrote about Shakespeare's plays, Johnson focused on how readers understand language. He also believed that plays should be realistic. While he praised Shakespeare, he also pointed out his faults, like sometimes being careless with plots or words. Johnson also stressed the importance of having a text that accurately showed what the author originally wrote, without changes from careless editors.

His Legacy Today

Many experts consider Johnson a great critic. Some say he is the only truly great critic in English literature. His ideas about how the mind works and how literature should be studied influenced literary theory in the 20th century.

Today, many of Johnson's letters, manuscripts, and books are kept at Harvard University. There are also many societies dedicated to studying his life and works. In 1984, on the 200th anniversary of his death, Oxford University held a big conference about him. In 1999, the BBC Four started the Samuel Johnson Prize, an award for non-fiction books. His Gough Square house in London has a special blue plaque to remember him. In 2009, he was featured on a special postage stamp in the United Kingdom. His death date, December 13, is remembered in the Church of England's Calendar of Saints. There is also a memorial to him at St Paul's Cathedral in London.

Major Works

| Essays, pamphlets, periodicals, sermons | |

| 1732–33 | Birmingham Journal |

| 1747 | Plan for a Dictionary of the English Language |

| 1750–52 | The Rambler |

| 1753–54 | The Adventurer |

| 1756 | Universal Visiter |

| 1756- | The Literary Magazine, or Universal Review |

| 1758–60 | The Idler |

| 1770 | The False Alarm |

| 1771 | Thoughts on the Late Transactions Respecting Falkland's Islands |

| 1774 | The Patriot |

| 1775 | A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland |

| Taxation no Tyranny | |

| 1781 | The Beauties of Johnson |

| Poetry | |

| 1728 | Messiah, a translation into Latin of Alexander Pope's Messiah |

| 1738 | London |

| 1747 | Prologue at the Opening of the Theatre in Drury Lane |

| 1749 | The Vanity of Human Wishes |

| Irene, a Tragedy | |

| Biographies, criticism | |

| 1735 | A Voyage to Abyssinia, by Jerome Lobo, translated from the French |

| 1744 | Life of Mr Richard Savage |

| 1745 | Miscellaneous Observations on the Tragedy of Macbeth |

| 1756 | "Life of Browne" in Thomas Browne's Christian Morals |

| Proposals for Printing, by Subscription, the Dramatick Works of William Shakespeare | |

| 1765 | Preface to the Plays of William Shakespeare |

| The Plays of William Shakespeare | |

| 1779–81 | Lives of the Poets |

| Dictionary | |

| 1755 | Preface to a Dictionary of the English Language |

| A Dictionary of the English Language | |

| Novellas | |

| 1759 | The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia |

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Johnson para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Johnson para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |