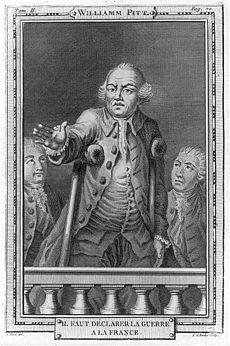

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of Chatham

|

|

|---|---|

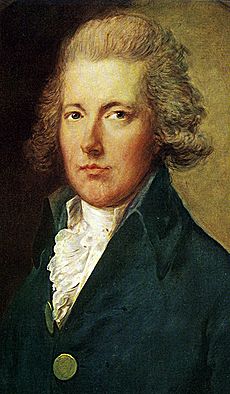

Pitt the Elder, after Richard Brompton

|

|

| Prime Minister of Great Britain | |

| In office 30 July 1766 – 14 October 1768 |

|

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Rockingham |

| Succeeded by | The Duke of Grafton |

| Lord Privy Seal | |

| In office 30 July 1766 – 14 October 1768 |

|

| Preceded by | The Duke of Newcastle |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Bristol |

| Leader of the House of Commons | |

| In office 27 June 1757 – 6 October 1761 |

|

| Preceded by | Himself |

| Succeeded by | George Grenville |

| In office 4 December 1756 – 6 April 1757 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry Fox |

| Succeeded by | Himself |

| Secretary of State for the Southern Department | |

| In office 27 June 1757 – 5 October 1761 |

|

| Preceded by | The Earl of Holderness |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Egremont |

| In office 4 December 1756 – 6 April 1757 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry Fox |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Holderness |

| Paymaster of the Forces | |

| In office 29 October 1746 – 25 November 1755 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Winnington |

| Succeeded by | |

| Member of Parliament | |

| In office 18 February 1735 – 4 August 1766 |

|

| Constituency |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Pitt

15 November 1708 Westminster, England |

| Died | 11 May 1778 (aged 69) Hayes, Kent, England |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey, England |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5; including Hester, John and William |

| Parent | Robert Pitt (father) |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Unit | King's Own Regiment of Horse |

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (born November 15, 1708 – died May 11, 1778) was an important British politician. He was a member of the Whig Party and served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. People often call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to tell him apart from his son, William Pitt the Younger, who also became a prime minister. Pitt was also known as the Great Commoner because he refused a noble title for a long time.

Pitt was a key leader in the British government from 1756 to 1761, especially during the Seven Years' War. This war included the French and Indian War in the American colonies. He led the government again from 1766 to 1768, holding the title of Lord Privy Seal. He was famous for his amazing public speaking skills. For much of his career, he was not in power and became well-known for criticizing the government. For example, he spoke out against corruption in the 1730s and the government's policies towards the American colonies in the 1770s.

Pitt is best remembered as Britain's leader during the Seven Years' War. He was determined to win against France, which helped Britain become a major world power. He was also popular with the public, stood against corruption, and supported the American colonies before the American Revolutionary War. Historians see him as one of Britain's most important prime ministers.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Pitt's Family Background

William Pitt's grandfather, Thomas Pitt (1653–1726), was known as "Diamond" Pitt. He got this nickname because he found a huge diamond and sold it for a lot of money. This deal, along with other business in India, made the Pitt family very rich. When his grandfather returned to England, he bought land and gained political power, controlling seats in Parliament.

William's father, Robert Pitt (1680–1727), was a MP. His mother was Harriet Villiers. Several of William's relatives were also MPs or important political figures, which helped the Pitt family's influence grow.

School and Health Challenges

William Pitt was born in Westminster on November 15, 1708. He went to Eton College from 1719, but he didn't like it there. He later said that a public school was good for "turbulent" boys but not for "gentle" ones. While at Eton, Pitt started to suffer from gout, a painful joint condition that affected him for the rest of his life.

In 1727, he went to Trinity College, Oxford. He read a lot, especially the Roman poet Virgil. In 1728, a severe gout attack forced him to leave Oxford without finishing his degree. He then traveled to the Dutch Republic and studied at Utrecht University, where he learned about international law.

Joining the Army

When Pitt returned home, he needed a job, so he decided to join the army. He became a cornet (a junior officer) in the dragoons. King George II later remembered Pitt's sharp criticisms, calling him "the terrible cornet of horse."

Pitt was frustrated because Britain was not fighting in the War of the Polish Succession, which began in 1733. He wanted to experience battle. His military career was short because his older brother gave him a seat in Parliament in 1735. Pitt then became a MP for Old Sarum.

Rising in Politics

The Patriot Whigs

Pitt quickly joined a group of Whigs who were unhappy with the government. They were called the Patriot Whigs and often met at Stowe House. This group opposed the government led by Sir Robert Walpole.

Pitt gave his first speech in Parliament in April 1736. He soon became a strong critic of the government. Because of his constant attacks, Walpole had him dismissed from the army in 1736. Many people saw this as unfair, believing that MPs should have the freedom to speak their minds without punishment. Pitt never got his army job back. However, Frederick, Prince of Wales, who also opposed the King, gave Pitt a job as one of his assistants. This new role allowed Pitt to continue his strong speeches against the government.

Pushing for War

In the 1730s, Britain's relationship with Spain worsened. British merchants complained about being mistreated by the Spanish, who accused them of smuggling. Pitt strongly argued for a tougher approach against Spain. He criticized Walpole's government for being too weak.

Public pressure led Britain to declare war on Spain in 1739. Britain had an early success at Porto Bello. But the war soon slowed down. Pitt claimed the government wasn't fighting effectively. A major attack on Cartagena in South America failed, with thousands of British troops dying, mostly from disease. This failure was seen as proof of the government's poor planning.

Later, the war with Spain became less important as Britain focused on fighting France in Europe during the War of the Austrian Succession. Pitt believed Britain missed a chance to weaken Spain.

Criticizing Hanoverian Spending

Walpole and the Duke of Newcastle focused on the war in Europe. They feared France would invade Hanover, which was connected to Britain through King George II. To prevent this, they decided to pay large sums of money (subsidies) to Austria and Hanover to raise troops.

Pitt strongly attacked these subsidies, playing on widespread anti-Hanoverian feelings in Britain. This made him popular with the public but earned him the King's lasting hatred. The King loved Hanover, where he had lived for 30 years. Because of Pitt's attacks, the government changed how they paid the money, sending it through Austria instead of directly to Hanover.

Walpole's Downfall

Many of Pitt's attacks were aimed directly at Walpole, who had been Prime Minister for 20 years. In February 1742, after bad election results and the failure at Cartagena, Walpole was finally forced to resign.

Pitt expected a new government where he would have a role, but he was left out. Walpole had secretly arranged for his allies to take over, so Pitt remained in opposition. In 1744, Pitt received a large gift of £10,000 from the Duchess of Marlborough. This was likely because she disliked Walpole and admired Pitt's opposition to him.

Serving in Government

Honest Paymaster

Eventually, King George II reluctantly agreed to give Pitt a government job. Pitt had changed his mind on some issues, like the Hanoverian subsidies, to make himself more acceptable. In February 1746, he became Vice-Treasurer of Ireland, and then in May, he was promoted to Paymaster of the Forces. This job gave him a place in the Privy Council.

As Paymaster, Pitt showed great honesty. It was common for paymasters to keep the interest from money held or to take a small percentage from foreign payments. Pitt refused to do this. He put all money in the Bank of England until it was needed and paid out all funds without taking any extra. He made sure everyone knew this, which greatly improved his reputation for honesty and for putting the country's interests first.

Disagreement with Newcastle

In 1754, the Prime Minister, Henry Pelham, died. His brother, the Duke of Newcastle, took over. Newcastle needed someone to lead the government in the House of Commons. Pitt and Henry Fox were the top choices, but Newcastle chose a less experienced diplomat, Sir Thomas Robinson. Many believed Newcastle did this because he feared Pitt and Fox's ambitions.

Pitt was disappointed but stayed in his job. However, he openly criticized Newcastle. From 1754, Britain was increasingly drawn into conflict with France, especially in North America. A British army was defeated in 1755, increasing tensions.

Newcastle tried to make treaties to gain allies by paying subsidies. Pitt and other politicians strongly opposed these payments. In November 1755, Pitt was fired from his job as Paymaster because he spoke out against the government's new subsidy plan. This created a rivalry between Pitt and Fox, which continued with their sons, William Pitt the Younger and Charles James Fox.

In 1756, Pitt's relationship with Newcastle got worse. Pitt claimed Newcastle deliberately left the island of Menorca undefended so the French would capture it. When Menorca fell in June 1756, public anger against Newcastle grew, forcing him to resign as Prime Minister.

Becoming Secretary of State

In December 1756, Pitt became Secretary of State for the Southern Department and Leader of the House of Commons. He told the new Prime Minister, the Duke of Devonshire: "My Lord, I am sure I can save this country, and no one else can."

Pitt insisted that Newcastle be kept out of the government, which made it hard for his government to last. The King was still unfriendly, and Newcastle still had a lot of influence. Despite this, the public strongly supported Pitt. He was dismissed from office in April 1757, but public demand for him was so strong that no other government could work without him. After weeks of talks, Pitt and Newcastle formed a new government. Pitt became the real leader, even though Newcastle was the official head.

Leading Britain to Victory

The Pitt–Newcastle Government

In June 1757, Pitt and Newcastle formed a new government that lasted until 1761. This partnership seemed unlikely just months before. Britain's war effort had been failing. They had lost Menorca, and their army in Hanover was retreating.

Pitt quickly started a more aggressive plan. He helped convince Hanover to rejoin the war. He also planned naval attacks on the French coast, though these were not very successful. In North America, a plan to capture Louisbourg was canceled due to a large French fleet.

Winning the Seven Years' War

In 1758, Pitt launched a new strategy for the Seven Years' War. He planned to keep many French troops busy in Germany while Britain used its strong navy to capture French lands around the world. He sent British troops to Europe to help the German army. This was a big change from his earlier views.

Pitt also sent expeditions to capture French trading posts in West Africa, which were very profitable. He also planned attacks on French islands in the Caribbean.

In North America, Britain successfully captured Louisbourg. British forces also took Fort Duquesne, which became Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh). This gave Britain control of the Ohio Country, a main cause of the war.

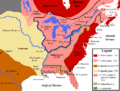

In 1759, known as the "Annus Mirabilis" (Year of Miracles), Britain had huge successes.

- In the Caribbean, Britain captured Guadeloupe.

- In India, the French failed to capture Madras.

- In North America, British troops captured Quebec after a major victory at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. This effectively ended the war in mainland North America.

- France planned to invade Britain, but their navy was defeated at Lagos and Quiberon Bay, stopping the invasion.

- In Germany, the French army was defeated at the Battle of Minden.

Britain ended 1759 victorious in every part of the world, and Pitt received the credit for these successes.

New King, New Challenges

In October 1760, King George II died, and his grandson, George III, became king. The new King did not like Pitt's policy of sending British troops to Germany. He preferred his friend, Lord Bute, who wanted to end Britain's involvement in the European war.

Pitt continued his plans for more conquests, including capturing Belle Île off the French coast in 1761. This was another blow to France. Pitt expected France to seek peace, but they could not agree on terms. Pitt refused to give France any share in Newfoundland, which was very important for its fishing industry.

Resignation and Peace Treaty

In 1761, Pitt learned about a secret agreement between France and Spain to form an alliance against Britain. Spain was worried about Britain's growing power. Pitt wanted to attack Spain's navy and colonies immediately, before Spain could prepare. However, Lord Bute and Newcastle refused, fearing it would make Britain look like the aggressor.

Pitt felt he had no choice but to resign in October 1761, since his advice on such an important matter was rejected. Many of his government colleagues were secretly happy to see him go, as they felt his power and popularity were too great.

After Pitt resigned, the King offered him a reward. Pitt received a pension of £3,000 a year, and his wife, Lady Hester Grenville, was made Baroness Chatham. Pitt refused a title for himself at this time. He promised the King he would not directly oppose the new government.

The war with Spain, which Pitt had wanted to start, did happen. But Pitt did not use this to criticize the government. He even supported their efforts to continue the war.

The Chatham Ministry

Becoming Earl of Chatham

In July 1766, Pitt was asked by the King to form a new government. Pitt wanted to choose people based on their skills, not their political connections. He chose the office of Lord Privy Seal, which meant he had to become a noble. On August 4, he became Earl of Chatham and Viscount Pitt.

Pitt's decision to accept a noble title was likely due to his poor health and desire for a less demanding role. However, the "Great Commoner" lost a lot of public support because of it. People had admired him for refusing a title.

His new government faced many challenges, including relations with France and Spain, tensions with the American colonies, and issues with the East India Company. One of his first actions was to stop the export of corn due to a bad harvest.

Challenges and Illness

In 1767, Charles Townshend, the finance minister, introduced new taxes on tea, paper, and other goods in the American colonies. These taxes were made without Pitt's full knowledge and angered the American colonists.

Pitt was also interested in the growing importance of India. However, he became very ill, both physically and mentally, during almost his entire time in office. He rarely met with his colleagues, and even refused a visit from the King. His illness meant he could not provide strong leadership, leading to unclear policies.

In October 1768, Chatham resigned due to his poor health, leaving the government to Grafton.

Later Life and Death

After resigning, Pitt's mental health improved as his gout got better. In July 1769, he appeared in public again, and in 1770, he returned to the House of Lords.

Falklands Crisis

In 1770, Britain and Spain almost went to war over the Falkland Islands. Pitt strongly argued for a tough stance against Spain and France. His speeches helped push the government to act firmly, which forced Spain to back down. Some people thought this crisis might bring Pitt back as Prime Minister, but instead, it strengthened the position of Lord North, who became Prime Minister and led the country for the next decade.

American War of Independence

Chatham tried to find a way to solve the growing conflict with the American colonies. He realized how serious the situation was. He proposed a "Provisional Act" that would keep Parliament's authority but also meet the colonists' demands, such as no taxation without their consent. However, the House of Lords rejected his idea in February 1775.

Pitt warned that America could not be conquered. Because of his stance, he was very popular among the American colonists.

Pitt's Final Moments

Pitt had little personal support by this time, but his speaking skills were as powerful as ever. He used them to argue against the government's policy in the conflict with America. His last appearance in the House of Lords was on April 7, 1778. He spoke against a motion to make peace with America, arguing that it meant giving in to France, whom he had spent his life trying to defeat.

After speaking for a long time, he rose again as if to speak, pressed his hand to his chest, and collapsed. His last words before he fell were: "My Lords, any state is better than despair; if we must fall, let us fall like men."

He was taken to his home, where his son William read to him from Homer. William Pitt the Elder died on May 11, 1778, at age 69.

He was buried in Westminster Abbey. Parliament voted for a public funeral and a monument to honor him. The monument shows Pitt above statues of Britannia (representing Britain) and Neptune (god of the sea).

In the Guildhall, an inscription by Edmund Burke summarized his impact: he was "the minister by whom commerce was united with and made to flourish by war." His family received a pension. His second son, William, would later become Prime Minister and add to the family's fame.

Pitt's Lasting Impact

People said that "Walpole was a minister given by the king to the people, but Pitt was a minister given by the people to the king." This shows that Pitt's power came from the support of the public, not just from Parliament. He was the first minister to truly understand that public opinion, though slow, is the most powerful force in the country. He used this power throughout his career.

Pitt helped start a big change in British politics, where the feelings of ordinary people began to influence the government daily. He was well-liked because his good qualities and even his flaws seemed very English. He could be inconsistent and bossy, and sometimes a bit overly formal, but these traits were mostly known only to those close to him.

To the public, he was seen as a statesman who was honest and could inspire great courage in those who worked for him. He was the most popular British minister because he was so successful in foreign policy. In domestic matters, his influence was small. He admitted he wasn't good with money.

Historians often call Pitt "the greatest British statesman of the eighteenth century." He is honored in St Stephen's Hall in Parliament.

The American city of Pittsburgh was named after Pitt after it was captured from the French during the Seven Years' War.

Family Life

Pitt married Lady Hester Grenville in 1754. They had five children:

- Lady Hester Pitt (1755–1780)

- John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham (1756–1835)

- Lady Harriet Pitt (1758–1786)

- Hon. William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806), who also became Prime Minister.

- Hon. James Charles Pitt (1761–1780), a Royal Navy officer.

Images for kids

-

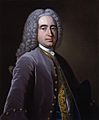

Lord Cobham, Pitt's commanding officer and political mentor. Pitt was part of a group of young MPs known as Cobham's Cubs.

-

The huge monument to William Pitt the Elder, in the Guildhall, London stands opposite an equally huge monument to his son, William Pitt the Younger in a balanced composition.

-

George II leading his forces to victory at the Battle of Dettingen (1743). Pitt angered the King by attacking British support for Hanover.

-

Pitt's longstanding rival Henry Fox.

-

Pitt the Elder, by William Hoare.

-

The Duke of Newcastle with whom Pitt formed an unlikely political partnership from 1757.

-

Lord Bute's rise to power between 1760 and 1762 influenced Britain's war effort. He favored ending British involvement on the continent.

-

Coat of arms of William Pitt.

-

Arms of William Pitt. Note that his arms form the basis for those of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and the University of Pittsburgh.

-

Robert Clive's victory at the Battle of Plassey established the East India Company as a military as well as a commercial power.

-

New borders drawn by the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

See also

In Spanish: William Pitt (el Viejo) para niños

In Spanish: William Pitt (el Viejo) para niños

- Grenvillite

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |