James Wolfe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Wolfe

|

|

|---|---|

"Major General Wolfe.

Who, at the Expence of his Life, purchas'd immortal Honour for his Country, and planted, with his own Hand, the British Laurel, in the inhospitable Wilds of North America, By the Reduction of Quebec, Septr. 13th. 1759." Portrait attributed to Joseph Highmore. |

|

| Born | 2 January 1727 Westerham, Kent, England |

| Died | 13 September 1759 (aged 32) Plains of Abraham, Quebec, New France |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1740–1759 |

| Rank | Major-general |

| Commands held | 20th Regiment of Foot |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations | Lieutenant-general Edward Wolfe (father) |

| Signature | |

James Wolfe (born January 2, 1727 – died September 13, 1759) was a brave British Army officer. He is famous for his new ways of training soldiers. As a major general, he is best known for his big victory in 1759. This was against the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec.

Wolfe was the son of a respected general, Edward Wolfe. He joined the army at a young age. He fought in many battles in Europe during the War of the Austrian Succession. His service in Flanders and Scotland helped him get noticed. He helped stop the Jacobite Rebellion in Scotland.

His career slowed down after a peace treaty in 1748. He spent eight years on duty in the Scottish Highlands. By age 18, he was already a brigade major. By 23, he was a lieutenant-colonel.

The Seven Years' War started in 1756, giving Wolfe new chances. He played a key role in a raid on Rochefort in 1757. This led William Pitt to make him second-in-command of a mission. Their goal was to capture the Fortress of Louisbourg.

After successfully taking Louisbourg, Wolfe became the commander of a new force. This force sailed up the Saint Lawrence River to capture Quebec City. After a long siege, Wolfe defeated the French army. It was led by the Marquis de Montcalm. This victory allowed British forces to take Quebec City. Wolfe was killed during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham from three musket shots. Montcalm also died the next day.

Wolfe's victory at Quebec in 1759 made him a lasting hero. He became a symbol of Britain's success in the Seven Years' War. His fame grew even more after the famous painting The Death of General Wolfe. People called him "The Hero of Quebec" and "The Conqueror of Canada." This is because taking Quebec led to taking Montreal. This ended French control of the colony in North America.

Contents

Early Life of James Wolfe

James Wolfe was born in Westerham, Kent, England. His birthday was January 2, 1727. He was the older of two sons. His father, Edward Wolfe, was a military veteran. His family had Anglo-Irish roots.

Wolfe's childhood home in Westerham is now called Quebec House. It is kept as a museum in his memory. The Wolfe family was close to the Warde family in Westerham. Wolfe's childhood friend, George Warde, later became a famous commander in Ireland.

Around 1738, his family moved to Greenwich. From a young age, Wolfe was set to have a military career. He joined his father's Marine regiment as a volunteer when he was just thirteen.

He got sick in 1740 and could not join a mission against Cartagena in South America. His father sent him home. He missed a terrible defeat for the British. Most of the soldiers died from disease during the Siege of Cartagena.

Wolfe's Early Military Career (1740–1748)

Fighting in Europe

In 1740, the War of the Austrian Succession began in Europe. Britain sent troops to help their ally, Austria, in 1742. James Wolfe received his first army job as a second lieutenant in 1741. He was in his father's Marine regiment.

The next year, he joined the 12th Regiment of Foot. He sailed to Flanders. There, he was promoted to Lieutenant. He also became an adjutant for his group of soldiers. His first year was quiet, with no major battles.

In 1743, his younger brother, Edward, joined the same regiment. The Wolfe brothers took part in a British attack. They moved into Southern Germany and faced a large French army. King George II himself led the army.

In June, the Allies were trapped by the river Main and surrounded by enemies. Instead of giving up, King George attacked the French near Dettingen. Wolfe's regiment fought hard, firing many musket shots. His regiment had the most casualties of any British group. Wolfe's horse was shot from under him.

The Allies drove off the French, who ran away. But King George did not chase them well, letting them escape. Still, the Allies stopped the French from entering Germany. This protected Hanover.

Wolfe's regiment at Battle of Dettingen impressed the Duke of Cumberland. He was near Wolfe during the battle. A year later, Wolfe became a Captain in the 45th Regiment of Foot. The 1744 campaign was frustrating, with no major battles. Wolfe was very sad when his brother Edward died that autumn, likely from tuberculosis.

Wolfe's regiment stayed to protect Ghent. This meant they missed the Allied defeat at the Battle of Fontenoy in May 1745. Wolfe's old regiment lost many soldiers there. After his regiment left Ghent, the French suddenly attacked and captured the town. Wolfe narrowly avoided becoming a French prisoner. He was then made a brigade major.

Fighting the Jacobite Rebellion

In July 1745, Charles Stuart landed in Scotland. He wanted to take back the British throne for his father. The Jacobites captured Edinburgh and won a battle in September. This made the British recall Cumberland and 12,000 troops from Flanders. Wolfe's regiment was among them.

The Jacobite army entered England in November. They reached Derby but turned back in December. This was mainly because they lacked English support. Wolfe was an aide-de-camp to Henry Hawley at Falkirk. He also fought at Culloden in April under Cumberland.

A story says Wolfe refused to shoot a wounded Highland officer after Culloden. This order supposedly came from Cumberland or Hawley. While Jacobite wounded were killed, and Hawley gave such orders, Wolfe's refusal cannot be confirmed. In fact, Wolfe wrote that "as few Highlanders are made prisoner as possible" during later raids.

Returning to Europe

In January 1747, Wolfe went back to Europe for the War of the Austrian Succession. He served under Sir John Mordaunt. The French had taken advantage of British troops being away. They captured Brussels in the Austrian Netherlands.

In 1747, the French wanted to capture Maastricht. Wolfe was part of Cumberland's army. They marched to protect the city from the French, led by Marshal Saxe. On July 2, Wolfe fought in the Battle of Lauffeld. He was badly wounded but praised for his service. Lauffeld was the biggest battle Wolfe fought in, with over 140,000 soldiers.

After their victory, the French captured Maastricht. They also took the fortress at Bergen op Zoom. Both sides were ready for more fighting, but a peace agreement stopped it.

In 1748, Wolfe returned to Britain. He was 21 and had fought in seven campaigns. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) ended the war. Britain and France agreed to return all captured lands.

Peace and Training (1748–1756)

Back home, Wolfe was sent to Scotland for garrison duty. A year later, he became a major. He took command of the 20th Regiment of Foot in Stirling. In 1750, Wolfe was confirmed as a Lieutenant colonel.

For eight years in Scotland, Wolfe wrote military guides. He also learned French by visiting Paris several times. He often felt sick, possibly from tuberculosis. But he worked hard to stay mentally sharp. He taught himself Latin and mathematics. When he could, he trained his body, especially improving his sword fighting skills.

In 1752, Wolfe took a long leave. He visited his uncle in Dublin, Ireland. He also saw Belfast and the Battle of the Boyne site. After a short stop at his parents' home, he went to France. In Paris, he often met the British Ambassador, Earl of Albemarle.

Wolfe asked to stay longer to watch French army exercises. But he was ordered home urgently. He rejoined his regiment in Glasgow. By 1754, Britain and France were close to war. Fighting had already started in North America.

Wolfe was very strict about discipline. In 1755, he ordered that any soldier who left their position during battle should be killed immediately. This showed how serious he was about military rules.

Seven Years' War (1754–1763)

In 1756, war officially broke out with France. Wolfe was promoted to Colonel. He was stationed in Canterbury, guarding Kent from a possible French invasion. He was upset by the news of the loss of Minorca in June 1756. He felt British forces lacked professionalism.

Even though many thought a French landing was coming, Wolfe doubted it. Still, he trained his men very carefully. He gave them clear fighting instructions.

As the invasion threat lessened, his regiment moved to Wiltshire. Despite early problems in the war, Britain was now ready to attack. Wolfe expected to play a big part. However, his health was getting worse. People thought he might have tuberculosis, like his younger brother. Many of his letters home spoke of the chance of an early death.

The Rochefort Raid

In 1757, Wolfe took part in a British amphibious attack on Rochefort. This was a French seaport on the Atlantic coast. The goal was to capture the town. It was also meant to help Britain's German allies, who were under French attack. Wolfe was chosen partly because he was friends with the commander, Sir John Mordaunt.

Wolfe was also the Quartermaster General for the whole mission. The force gathered on the Isle of Wight. After weeks of delays, they finally sailed on September 7.

The attack failed. After taking an island offshore, the British did not try to land on the mainland. They did not push on to Rochefort. Instead, they went home. Their sudden appearance caused panic in France, but had little real effect. Mordaunt was tried in a court-martial for failing to attack, but he was found not guilty.

Wolfe was one of the few who did well in the raid. He went ashore to check the land. He constantly urged Mordaunt to attack. At one point, he told the General he could capture Rochefort with just 500 men. But Mordaunt refused. Wolfe was annoyed by the failure. But he learned important lessons about amphibious warfare. These lessons helped him later at Louisbourg and Quebec.

Because of his actions at Rochefort, Wolfe was noticed by Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder. Pitt decided that North America was the best place to win the war. He planned to attack French Canada. Pitt chose to promote Wolfe over many older officers.

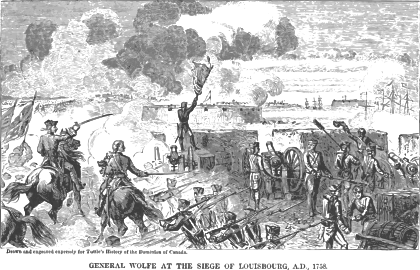

Capturing Louisbourg

On January 23, 1758, James Wolfe was made a Brigadier general. He was sent with Major General Jeffrey Amherst. They joined Admiral Boscawen's fleet to attack Fortress of Louisbourg in New France. Louisbourg was near the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River. Capturing it was vital for any attack on Canada from the east.

An earlier mission had failed to take the town. This was because of a French naval build-up. For 1758, Pitt sent a much larger British Navy force. Wolfe did very well in preparing for the attack. He also led the first landing and the aggressive advance of the siege cannons. The French surrendered in June of that year during the Siege of Louisbourg (1758). Wolfe then helped with the Expulsion of the Acadians in the Gulf of St. Lawrence campaign (1758).

The British had planned to move along the St. Lawrence and attack Quebec that year. But winter came, forcing them to wait until the next year. A plan to capture New Orleans was also rejected. Wolfe returned home to England. His role in taking Louisbourg made him famous in Britain for the first time. The victory news was mixed with the failure of a British force moving towards Montreal. This force was defeated at the Battle of Carillon. Also, George Howe, a respected young general, died. Wolfe called him "the best officer in the British Army."

The Quebec Campaign (1759)

Wolfe's New Command

Because Wolfe had done so well at Louisbourg, William Pitt the Elder chose him to lead the British attack on Quebec City the next year. While in Canada, Wolfe was given the local rank of Major general. But in Europe, he was still a full colonel.

Amherst was made Commander-in-Chief in North America. He would lead a separate, larger force to attack Canada from the south. Wolfe insisted on his friend, the Irish officer Guy Carleton, as Quartermaster General. He threatened to quit if Carleton was not chosen. Once this was agreed, he began preparing to leave. Pitt wanted to focus on North America again. He planned to weaken France by sailing back to India.

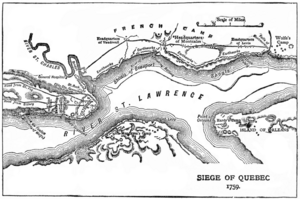

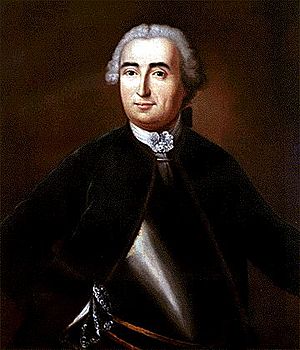

Sailing Up the Saint Lawrence

Even with many British troops in North America, the plan divided the army. This meant that when Wolfe reached Quebec, the French commander Louis-Joseph de Montcalm had more local troops. He had gathered many Canadian militia to defend their homeland. The French first thought the British would come from the east. They believed the St. Lawrence River was too hard for a large army. So, they prepared to defend Quebec from the south and west.

But the British plans were found. This gave Montcalm several weeks to make Quebec's defenses stronger against Wolfe's water attack.

Montcalm's main goal was to stop the British from taking Quebec. This would keep a French presence in Canada. The French government thought a peace treaty would happen the next year. So, they focused on winning in Germany and planning an invasion of Britain. They hoped this would help them get back captured lands. For this plan to work, Montcalm just needed to hold out until winter. Wolfe had a short time to capture Quebec in 1759 before the St. Lawrence froze. If it froze, his army would be trapped.

Wolfe's army gathered at Louisbourg. He expected 12,000 men. But he only had about 400 officers, 7,000 regular soldiers, and 300 gunners. Wolfe's troops had help from a fleet of 49 ships and 140 smaller boats. Admiral Charles Saunders led this fleet. Wolfe was eager to start. After some delays, he went ahead with only part of his force. He left orders for more troops to follow him up the St. Lawrence.

The Siege of Quebec

The British army surrounded the city for three months. During this time, Wolfe wrote a document called Wolfe's Manifesto. He sent it to French-Canadian civilians. This was part of his plan to scare them. In March 1759, before reaching Quebec, Wolfe wrote to Amherst: "If we cannot take Quebec, I will burn the town with shells. I will destroy crops, houses, and animals. I will send as many Canadians as possible to Europe. I will leave hunger and ruin behind me."

This manifesto was not very helpful. It made many neutral people actively fight the British. This increased the number of militia defending Quebec to as many as 10,000.

After a long but undecided bombing of the city, Wolfe tried an attack north of Quebec at Beauport. The French were strongly dug in there. As weeks passed, the British chances of winning became smaller. Wolfe grew sad. Amherst's large army moving on Montreal was very slow. This meant Wolfe would not get any help from him.

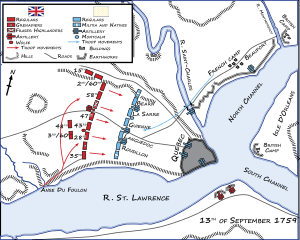

The Battle and Wolfe's Death

Wolfe then led 4,400 men in small boats. They made a very bold and risky landing at the bottom of the cliffs west of Quebec. This was along the Saint Lawrence River. His army, with two small cannons, climbed the 200-meter cliff early on September 13, 1759. They surprised the French, led by the Marquis de Montcalm. Montcalm thought the cliff could not be climbed.

The French faced the chance that the British would bring more cannons up the cliffs. These cannons could knock down the city's walls. So, the French fought the British on the Plains of Abraham. They were defeated after just fifteen minutes of battle. But as Wolfe moved forward, he was shot three times. Once in the arm, once in the shoulder, and finally in the chest.

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham caused the deaths of both top commanders. Montcalm died the next day from his wounds. Wolfe's victory at Quebec helped the Montreal Campaign the next year. With Montreal's fall, French rule in North America ended. Only Louisiana and the tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon remained.

Wolfe's body was returned to Britain on HMS Royal William. He was buried in his family's tomb in St Alfege Church, Greenwich. His father, who died in March 1759, was also buried there. The funeral was on November 20, 1759. This was the same day Admiral Hawke won the last of the three great victories of the "Wonderful Year" – Minden, Quebec, and Quiberon Bay.

Wolfe's Personality

Wolfe was known by his soldiers for being tough on himself and on them. He also carried the same fighting gear as his regular soldiers. This included a musket, cartridge box, and bayonet. This was unusual for officers back then. Even though he often got sick, Wolfe was active and restless. Amherst said Wolfe seemed to be everywhere at once.

There's a story that someone at the British Court called the young Brigadier "mad." King George II supposedly replied, "Mad, is he? Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals." Wolfe was a well-read man. Before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, he is said to have recited Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard to his officers. This poem includes the line "The paths of glory lead but to the grave." Wolfe added: "Gentlemen, I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec tomorrow."

After being rejected in love, he wrote to his mother in 1751. He said he would probably never marry. He believed people could easily live without marrying. A story published after Wolfe's death says he carried a locket with a picture of Katherine Lowther. She was supposedly his fiancée. The story claims he gave the locket to First Lieutenant John Jervis the night before he died. Wolfe supposedly knew he would die in battle. Jervis then faithfully returned the locket to Lowther.

Wolfe's Lasting Impact

The monument in Quebec City, marking the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, once read: "Here Died Wolfe Victorious." To avoid upsetting French-Canadians, it now simply says: "Here Died Wolfe."

Wolfe's defeat of the French led to Britain taking the New France area of Canada. His "hero's death" made him a legend in his home country. The Wolfe legend inspired the famous painting The Death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West. It also led to the folk song "Brave Wolfe" and the first line of the Canadian anthem, "The Maple Leaf Forever".

In 1792, after Quebec was divided into provinces, John Graves Simcoe, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, named islands after the victorious generals. These included Wolfe Island, Amherst Island, Howe Island, Carleton Island, and Gage Island (now Simcoe Island).

In 1832, the first war monument in what is now Canada was built where Wolfe supposedly fell. It is a column with a helmet and sword. An inscription says, in French and English, "Here died Wolfe – 13 September 1759."

Wolfe's Landing National Historic Site of Canada is in Kennington Cove, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. It is part of the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site. This is where British forces launched their successful attack on Louisbourg in 1758. Wolfe's Landing became a national historic site in 1929.

There is a memorial to Wolfe in Westminster Abbey by Joseph Wilton. The 3rd Duke of Richmond, who served with Wolfe, ordered a bust of him. A painting called "Placing the Canadian Colours on Wolfe's Monument in Westminster Abbey" is in Currie Hall at the Royal Military College of Canada.

A statue of Wolfe overlooks the Royal Naval College in Greenwich. This spot offers great views of London. Another statue is in his hometown of Westerham, Kent. At Stowe Gardens in Buckinghamshire, there is an obelisk called Wolfe's obelisk. Wolfe spent his last night in England at the mansion there.

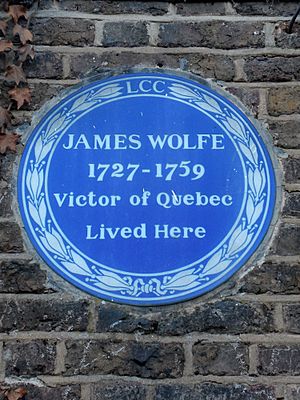

Wolfe is buried under the Church of St Alfege, Greenwich. There are four memorials to him there. The local primary school is also named after him. The house where he lived in Greenwich, Macartney House, has a blue plaque with his name. A nearby road is called General Wolfe Road.

In 1761, George Warde, a childhood friend of Wolfe's, started the Wolfe Society. It still meets yearly in Westerham to remember him. Warde also paid for a painting called "The Boyhood of Wolfe." It is now at Quebec House, Wolfe's childhood home. Warde also built a monument in Squerres Park where Wolfe got his first army job.

In 1979, Crayola crayons made a "Wolfe Brown" color. It was stopped the next year.

Many places in Canada are named after him. There are important monuments to Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham and near Parliament Hill in Ottawa. In 1792, Ontario Governor John Graves Simcoe named Wolfe Island in Lake Ontario after him. On September 13, 2009, the Wolfe Island Historical Society celebrated the 250th anniversary of Wolfe's victory at Quebec. A life-size statue of Wolfe is planned.

South Mount Royal Park, Calgary has a James Wolfe statue since 2009. It was originally in New York City. It was sculpted in 1898 by John Massey Rhind.

A senior girls' house at the Duke of York's Royal Military School is named after Wolfe. There is also a James Wolfe school for children in Greenwich.

His letters from age 13 until his death are kept at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in Toronto. Other items owned by Wolfe are in museums in Canada and England. Wolfe's cloak, worn at Louisbourg and Quebec, is part of the British Royal Collection. In 2008 and 2009, it was shown in exhibits in Nova Scotia. Wolfe Crescent in Halifax, Nova Scotia, is named after him.

Point Wolfe is in Fundy National Park. The town of Wolfeboro, New Hampshire is also named after Wolfe. In Montreal, Rue Wolfe runs next to Rue Montcalm and Rue Amherst. In Quebec City, an avenue is named after him.

See also

In Spanish: James Wolfe para niños

In Spanish: James Wolfe para niños

- General Wolfe's Song

- The Maple Leaf Forever – another Canadian song glorifying General Wolfe.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |