New France facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

New France

Nouvelle-France (French)

|

|

|---|---|

| 1534–1763 | |

|

Motto:

|

|

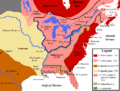

Location of New France (green) maximal expansion in 1712, before Treaty of Utrecht.

|

|

| Status | Viceroyalty of the Kingdom of France |

| Capital | Quebec |

| Common languages | French |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| King of France | |

|

• 1534–1547

|

Francis I (first) |

|

• 1715–1763

|

Louis XV (last) |

| Viceroy of New France | |

|

• 1534–1541

|

Jacques Cartier (first; as Governor of New France) |

|

• 1755–1760

|

Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil (last) |

| Legislature | Superior Council |

| Historical era | Colonial/French and Indian War |

|

• Exploration of Canada begins with Jacques Cartier

|

24 July 1534 |

|

• Louis XIV integrated New France into the royal domain, endowed it with a new administration and founded the French West India Company

|

18 September 1663 |

|

• By the Treaty of Utrecht, France ceded most of Acadia to the Kingdom of Great Britain as well as its claims on Newfoundland and Hudson's Bay.

|

11 April 1713 |

| 10 February 1763 | |

| Area | |

| 8,000,000 km2 (3,100,000 sq mi) | |

| Currency | Livre tournois |

| Today part of | Canada United States Saint Pierre and Miquelon |

New France (French: Nouvelle-France) was a huge area in North America that France claimed and settled. This adventure began in 1534 when Jacques Cartier explored the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It ended in 1763 when France gave up New France to Great Britain and Spain after the Treaty of Paris.

At its largest in 1712, New France stretched from Newfoundland to the Canadian Prairies. It went from Hudson Bay all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. This included all the Great Lakes of North America. It had five main parts: Canada, Hudson Bay, Acadie, Terre-Neuve (on Newfoundland island), and Louisiane.

In the 1500s, the French mainly used these lands to trade for valuable furs with different Indigenous peoples. In the 1600s, successful settlements started in Acadia and Quebec. But in 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht made France give up its claims to most of Acadia, Hudson Bay, and Newfoundland to Great Britain. France then built the Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island to protect its remaining lands.

The number of people living in New France grew slowly but steadily. By 1754, there were about 69,000 people. This included 10,000 Acadians, 55,000 Canadiens, and 4,000 settlers in Louisiana. From 1755 to 1764, the British forced many Acadians to leave their homes. This event is called the Great Upheaval. Their descendants now live in Canada's Maritime provinces, and in Maine and Louisiana in the United States.

After the Seven Years' War (which included the French and Indian War in America), France lost most of New France. In the 1763 Treaty of Paris, France gave Canada, Acadia, and French Louisiana east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain. Spain received Louisiana west of the Mississippi River. Later, in 1800, Spain secretly gave its part of Louisiana back to France. But in 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte sold it to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase. This was the end of French colonial efforts on the American mainland.

Today, New France is part of the United States and Canada. The only small part of French rule left is the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon. These are still a French territory. However, Quebec in Canada remains mostly French-speaking. In the United States, you can still see the legacy of New France in many place names and small French-speaking communities.

Early European Exploration (1523–1650s)

Around 1523, an Italian explorer named Giovanni da Verrazzano convinced King Francis I of France to send him on a trip. The king wanted to find a western sea route to China. Verrazzano sailed from France and explored the coast of what is now the Carolinas. He then went north and anchored in New York Bay.

Verrazzano was the first European to visit the area of modern-day New York. He named it Nouvelle-Angoulême to honor the king. His journey made the king want to start a colony in this new land. Verrazzano called the land between Spanish Mexico and English Newfoundland Francesca and Nova Gallia.

In 1534, Jacques Cartier placed a cross on the Gaspé Peninsula. He claimed the land for King Francis I. This became the first part of New France. In 1541, a settlement of 400 people was tried at Fort Charlesbourg-Royal (near present-day Quebec City). But it only lasted for two years.

French fishing boats kept sailing to the Atlantic coast and into the St. Lawrence River. They made friends with Canadian First Nations. These friendships became very important when France started to settle the land. French traders soon found that the St. Lawrence region had many valuable fur-bearing animals, especially beavers. Beavers were becoming rare in Europe. Because of this, the French king decided to colonize the area. This would help France gain more power in America.

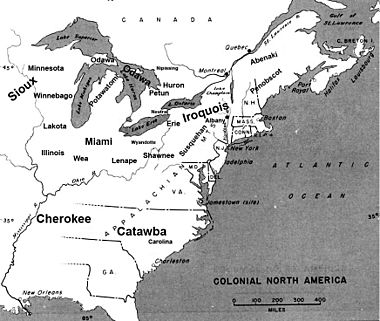

Acadia and Canada (New France) were home to Indigenous peoples. These included nomadic Algonquian peoples and settled Iroquoian peoples. These lands had many valuable natural resources that interested all of Europe. By the 1580s, French trading companies were set up to bring back furs. We don't know much about what happened between the Indigenous people and Europeans back then because there are not many records.

Other attempts to create lasting settlements also failed. In 1598, a French trading post on Sable Island off Acadia did not work out. In 1600, a trading post at Tadoussac was set up, but only five settlers survived the winter.

In 1604, a settlement was started at Île-Saint-Croix. It was moved to Port-Royal in 1605. This settlement was abandoned in 1607, restarted in 1610, and destroyed in 1613. After that, settlers moved to other nearby places. These new settlements were known as Acadia, and the people were called Acadians.

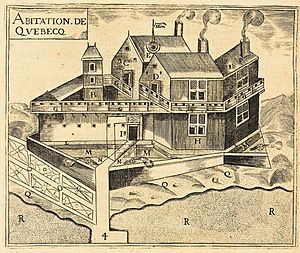

Founding Quebec City (1608)

In 1608, King Henry IV supported Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons and Samuel de Champlain. They founded Quebec City with 28 men. This was the second lasting French settlement in Canada. Settling the land was slow and hard. Many settlers died early due to harsh weather and diseases. By 1630, only 103 colonists lived there. But by 1640, the population grew to 355.

Champlain quickly made friends with the Algonquin and Montagnais peoples. They were at war with the Iroquois. In 1609, Champlain and two French friends joined their Algonquin, Montagnais, and Huron allies. They traveled south from the St. Lawrence Valley to Lake Champlain. Champlain played a key role in a battle against the Iroquois there. This battle helped Champlain build strong ties with the Huron and Algonquin. These ties were vital for France's fur trade.

Champlain also arranged for young French men to live with Indigenous people. They learned their languages and customs. This helped the French adapt to life in North America. These coureurs des bois ("runners of the woods"), like Étienne Brûlé, spread French influence. They went south and west to the Great Lakes and among the Huron tribes. For almost a century, the Iroquois and French often fought each other.

For the first few decades, only a few hundred French people lived in the colony. The English colonies to the south were much bigger and richer. Cardinal Richelieu, an advisor to King Louis XIII, wanted New France to be as important as the English colonies. In 1627, Richelieu started the Company of One Hundred Associates. This company invested in New France. It promised land to hundreds of new settlers. It also aimed to make Canada an important trading and farming colony. Richelieu named Champlain as the Governor of New France. He also said that non-Roman Catholics could not live there. So, many Protestants moved to the English colonies instead.

The Roman Catholic Church and missionaries like the Recollets and Jesuits became very strong in New France. Richelieu also brought in the seigneurial system. This was a farming system where land was given out in long, narrow strips. It remained a key feature of the St. Lawrence valley until the 1800s. Richelieu's efforts did not greatly increase the French population. But they did prepare the way for future success.

At the same time, the English colonies to the south started attacking the St. Lawrence Valley. They even captured Quebec until 1632. Champlain returned to Canada that year. He asked for another trading post to be built at Trois-Rivières. This was done in 1634. Champlain died in 1635.

In 1646, a ship named Le Cardinal arrived in Quebec. It brought Jules (Gilles) Trottier II and his family. They were part of the Company of Habitants, which mainly traded furs.

Royal Control and Settlement Growth

By 1650, New France had only seven hundred colonists. Montreal had just a few dozen settlers. Since Indigenous people did most of the beaver hunting, the French company needed few French workers. New France was so small that it almost fell to hostile Iroquois forces. In 1660, a settler named Adam Dollard des Ormeaux led a Canadian and Huron militia against a much larger Iroquois force. None of the Canadians survived, but they did stop the Iroquois invasion.

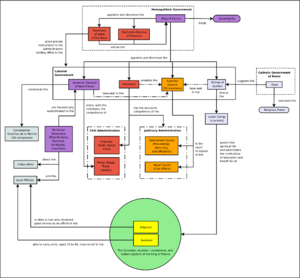

In 1627, Quebec had only eighty-five French colonists. It was easily taken by three English privateers two years later. In 1663, New France finally became safer. King Louis XIV made it a royal province. This took control away from the Company of One Hundred Associates. In the same year, the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal gave its lands to the Seminaire de Saint-Sulpice.

The King paid for trips across the ocean and offered other reasons for people to move to New France. After this, the population of New France grew to three thousand.

In 1665, Louis XIV sent a French army, the Carignan-Salières Regiment, to Quebec. The colonial government was changed to be like the government in France. The Governor General and Intendant reported to the French Minister of the Marine. In 1665, Jean Talon became the first Intendant of New France. These changes reduced the power of the Bishop of Quebec. The Bishop had held the most power after Champlain's death.

Talon tried to change the seigneurial system. He made seigneurs (landlords) live on their land and limited the size of their seigneuries. He wanted to make more land available for new settlers. Talon's plans did not work well. Very few new settlers arrived, and the industries he started did not become as important as the fur trade.

Settlers and Families

The first settler brought to Quebec by Champlain was a pharmacist named Louis Hébert and his family. They came specifically to live and stay in New France to help the settlement grow. More people came when there was a need for specific skills, like farmers, builders, and blacksmiths. The government also encouraged marriages with Indigenous peoples. They also welcomed indentured servants, called engagés, who were sent to New France. When couples married, they were given money to have large families, which worked well.

By 1672, the population of New France had grown to 6,700 people. This was a big increase from 3,200 people in 1663.

This fast growth in population happened because there was a high demand for children and plenty of natural resources to support them. People in Canada had a very good diet for their time. This was because of lots of meat, fish, and clean water. Food also stayed fresh during the winter, and there was enough wheat most years. As a result, women in the colony had about 30% more children than women in France.

Besides housework, some women also worked in the fur trade. This was the main way to make money in New France. They worked at home with their husbands or fathers as merchants and suppliers. Some widows even took over their husbands' businesses. Some women became independent business owners.

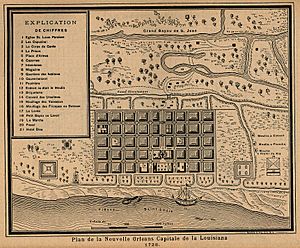

Settlements in Louisiana

The French expanded their claims south and west of the American colonies in the late 1600s. They named this new territory La Louisiane after King Louis XIV. In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle explored the Ohio River Valley and the Mississippi River Valley. He claimed the entire area for France, all the way south to the Gulf of Mexico.

La Salle tried to start the first southern colony in this new territory in 1685. But due to bad maps, he ended up building his Fort Saint Louis in what is now Texas. The colony suffered from disease. The remaining settlers were killed in 1688 by an attack from the local Indigenous population. Other parts of Louisiana, like New Orleans and southern Illinois, were settled successfully. They left a strong French influence in these areas even after the Louisiana Purchase.

Many important forts were built in New France. Governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac ordered these forts to be built. Forts were also built in older parts of New France that had not yet been settled. Many of these forts were guarded by the Troupes de la Marine. These were the only regular soldiers in New France between 1683 and 1755.

Growing Settlements and Economy

The European population grew slowly under French rule. Most growth came from births, not from many new people moving in. Most French settlers were farmers. The number of children born to these settlers was very high. Women had about 30 percent more children than women in France. Historians say that people in Canada had a great diet for their time. The 1666 census of New France was the first count of people in North America. It was done by Jean Talon, the first Intendant of New France, between 1665 and 1666. This census showed 3,215 people in New France, in 538 families. There were many more men (2,034) than women (1,181).

By the early 1700s, settlers in New France were well established along the Saint Lawrence River and the Acadian Peninsula. Their population was around 15,000 to 16,000. The first population numbers for Acadia in 1671 showed only 450 people.

After the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, New France began to do better. Industries like fishing and farming, which had failed earlier, started to succeed. A "King's Highway" (Chemin du Roy) was built between Montreal and Quebec to help trade move faster. The shipping industry also grew as new ports were built and old ones were improved. The number of colonists greatly increased. By 1720, Canada was able to support itself, with a population of 24,594.

Mainly due to natural births and some people moving from Northwest France, the population of Canada grew to 55,000 by 1754. This was an increase from 42,701 in 1730. By 1765, the population was almost 70,000.

By 1714, the Acadian population had grown to over 2,500. By the late 1750s, it reached about 13,000 people. This growth was mostly from natural births, not from many new people moving in.

The European population of Louisiana was estimated at 5,000 by the 1720s. This changed a lot in the mid-1730s when 2,000 French settlers were lost and African slaves were brought in. By the end of French rule, enslaved men, women, and children made up about 65 percent of Louisiana's 6,000 non-Indigenous people.

Fur Trade and Economy

The economy of New France changed over time. First, it was based on fishing in the Atlantic. Later, as French settlers moved inland, the economy focused on the North American fur trade. Furs, especially beaver furs, became the main product that made New France's economy strong. This was especially true for Montreal.

The trading post of Ville-Marie, on the island of Montreal, quickly became the center of the French fur trade. Its location on the St. Lawrence River was perfect. From here, a new economy grew, offering more chances for people in New France to make money. In 1627, the Company of New France was given the right to collect and sell furs from French lands. By trading with various Indigenous groups, the company grew powerful. It could set prices for furs and other goods.

The fur trade involved small but very valuable goods. This attracted a lot of money and attention. In Montreal, farming did not grow much. It was mostly for feeding the settlers, not for trade outside the French colony. This shows how the fur trade held back other parts of the economy.

However, by the early 1700s, the fur trade slowly changed Montreal. It became a city of merchants and bright lights, not just small traders. The fur trade also helped other businesses grow. For example, some tanneries (places that make leather) were built in Montreal. Many inns, taverns, and markets also opened to support the growing number of people who depended on the fur trade. By 1683, there were over 140 families and possibly 900 people living in Montreal.

The founding of the Compagnie des Indes in 1718 again showed how important the fur trade was. This company, like the earlier Company of New France, tried to control the fur trade. It set prices, supported government sales taxes, and fought against illegal trading. However, by the mid-1700s, the fur trade was slowly declining.

There were fewer furs available, and the supply could not meet the demand. This led to the removal of a 25 percent sales tax that was meant to cover New France's costs. Also, with fewer furs, more illegal trading happened. More Indigenous groups and fur traders started trading with British or Dutch merchants to the south, instead of with New France.

By the end of French rule in New France in 1763, the fur trade had lost much of its importance. It was no longer the main product supporting New France's economy. Still, it was the main reason Montreal and the French colony grew so much.

Coureurs des bois and Voyageurs

The coureurs des bois were key to starting trade from Montreal. They carried French goods into distant lands. In return, Indigenous people brought furs back to Montreal. The coureurs traveled with trading tribes. These tribes often tried to stop the French from reaching more distant fur-hunting tribes. Still, the coureurs kept pushing outward. They used the Ottawa River as their first step, always starting from Montreal. The Ottawa River was important because it offered a route that avoided the Iroquois territory. This is why Montreal and the Ottawa River area were central to Indigenous warfare and rivalries.

Montreal faced problems because too many coureurs were out in the woods. The large amount of furs coming back caused too many furs on the markets in Europe. This made it hard to control the coureurs' trade because they easily avoided rules, monopolies, and taxes.

These issues caused a big disagreement in the colony. In 1678, a meeting decided that trade should be done in public. This was to better protect Indigenous people. It was also forbidden to take alcohol inland to trade with Indigenous groups. However, these rules for the coureurs never really worked. The fur trade continued to rely on alcohol. And it stayed largely in the hands of the coureurs who traveled north for furs.

Over time, the Coureurs des bois were partly replaced by official fur trading groups. The main canoe workers for these groups were called voyageurs.

Indigenous Peoples

The French and Algonquins first met in 1603. This was after Samuel de Champlain set up France's first lasting North American settlement along the St. Lawrence River. In 1610, the Algonquins helped strengthen their ties with the French by guiding Étienne Brûlé into the Canadian interior.

The relationship between the Iroquois and the French began in 1609. Samuel De Champlain fought against the Iroquois. Champlain traveled from the St. Lawrence Valley with his Algonquin, Montagnais, and Huron friends. He killed three Iroquois chiefs on Lake Champlain with his first shots. After this, the Iroquois and French were often at war until the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701.

The French wanted to use the land for the fur trade and later for timber. Even with their tools and guns, French settlers depended on Indigenous people to survive the harsh climate in North America. Many settlers did not know how to survive the winter. Indigenous people taught them how to hunt for food and use furs for warm clothing. Historians note that while relations with Indigenous peoples were often good, French officials in Paris saw cooperation as annoying. Far from the colonies, French courtiers often criticized New French officials for even talking with Indigenous nations.

As the fur trade became the main economy, French traders often married or formed relationships with Indigenous women. This helped the French build ties with their wives' Indigenous nations. These ties gave them protection and access to hunting and trapping grounds.

One specific Indigenous group that came from these relationships is the Métis people. They are descendants of marriages between French men and Indigenous women. Their name comes from an old French word for "person of mixed background." At first, the French encouraged these relationships. They hoped it would help Indigenous people adopt French culture and strengthen alliances. But as the Métis started to become their own culture around the 1700s, the French began to discourage these relationships. Many Métis families moved to western Canada because of this and for fur trading opportunities. A major settlement at this time was in the Red River Valley. This area was important for the fur trade. This was the start of the modern Métis nation. Modern Canada legally recognized them as a protected Indigenous group in the Constitution Act, 1982.

The fur trade also helped Indigenous people. They traded furs for metal tools and other European goods that made their lives easier. Tools like knives, pots, kettles, nets, firearms, and hatchets improved their lives. However, while daily life became easier, some traditional ways of doing things changed. Indigenous people used many of these new tools, but they also were exposed to less helpful trade goods, like alcohol and sugar. The Iroquois, like most tribes, started to rely on European goods, especially firearms. This led to a big drop in the beaver population in the Hudson Valley. This decline caused the fur trade to move further north, along the St. Lawrence River.

England Enters the Fur Trade

Since Henry Hudson claimed Hudson Bay and the surrounding lands for England in 1611, English colonists began to expand. They moved across what is now the Canadian north, beyond French New France. In 1670, King Charles II of England gave a special paper to Prince Rupert. This paper gave "the Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay" the sole right to harvest furs in Rupert's Land. This land drained into Hudson Bay. This was the start of the Hudson's Bay Company. It was helped by French coureurs des bois, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers. They were unhappy with French rules. Now, both France and England were officially involved in the Canadian fur trade.

The Economy of La Louisiane

The Mississippi River was very important for trade in the Louisiana Purchase territory. New Orleans, the largest city in the territory, was the most important trading city in the United States until the Civil War. Most jobs there were related to trade and shipping, not manufacturing. The first commercial shipment down the Mississippi River was of deer and bear hides in 1705. The area of Louisiana was not clearly defined at first. It stretched as far east as what is now Mobile, Alabama, which French settlers started in 1702.

The French (and later Spanish) Louisiana Territory was owned by France for many years. But it was losing money. So, in 1713, it was given to a French banker named Antoine Crozat for 15 years. After losing four times his investment, Crozat gave up his rights in 1717. Control of Louisiana and its 700 people was given to the Company of the Indies in 1719. This company started a big program to get European settlers to move to the territory. Unemployed people and convicts were also sent to Louisiana. After the company went bankrupt in 1720, control went back to the king.

King Louis XV did not see much value in Louisiana. To make up for Spain's losses in the Seven Years' War, he gave Louisiana to his cousin Charles III in 1762. Louisiana stayed under Spanish control until Napoleon demanded it be returned to France. Even though Louisiana belonged to France by a secret treaty in 1800, Spain continued to manage it until the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. After the United States bought the territory, its population tripled between 1803 and when Louisiana became a state in 1812.

Religion in New France

Before Europeans arrived, First Nations people followed many different animistic religions. During the time of the colonies, the French settled along the Saint Lawrence River. These were mainly Catholics, including many Jesuits. They worked hard to convert the Indigenous population, and they were successful.

The Catholic Church became very powerful in New France after Champlain died. It wanted to create a Christian community in the colony. In 1642, they supported a group of settlers led by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve. They founded Ville-Marie, which is now Montreal, further up the St. Lawrence River. Throughout the 1640s, Jesuit missionaries went into the Great Lakes region. They converted many of the Huron. The missionaries often clashed with the Iroquois, who frequently attacked Montreal.

The Huron needed French goods for daily life and for fighting. The French would not trade with Indigenous groups who refused to work with missionaries. So, the Huron were more likely to become Christian. The Huron also relied heavily on European goods for their burial ceremonies, known as The Huron Feast of the Dead. Trading with the French allowed them to bury more decorative goods during ceremonies. With many deaths from growing epidemics, the Huron could not afford to lose ties with the French. They feared angering their ancestors.

Jesuit missionaries explored the Mississippi River, including the Illinois Country. Father Jacques Marquette and explorer Louis Jolliet traveled in a small group. They started from Green Bay and went down the Wisconsin River to the Mississippi River. They talked with the tribes they met along the way. Although Spanish trade goods had reached most Indigenous peoples, these were the first Frenchmen to connect with the tribes in the area named for the Illinois, including the Kaskaskia. They kept detailed notes of what they saw and the people they met. They sketched what they could and mapped the Mississippi River in 1673. Their travels were described as first contacts with the Indigenous peoples, even though there was clear evidence of contact with Spanish people from the south.

After French children arrived in Quebec in 1634, measles also came with them. The disease quickly spread among Indigenous peoples. Jesuit priest Jean de Brébeuf said the symptoms were severe. Brébeuf believed that the Indigenous peoples' fearlessness towards death from this disease made them perfect for converting to Christianity. Indigenous peoples thought that if they did not convert, they would be exposed to the priests' evil magic that caused the illness.

Jesuit missionaries were concerned by the lack of male leadership in Indigenous communities. Indigenous women were highly respected in their societies. They took part in political and military decisions. Jesuits tried to change this system. They wanted to shift the power of men and women to match European societies. They would tell Indigenous women, "In France, women must obey their masters, their husbands." Jesuits tried to explain this to Indigenous women, hoping to teach them proper European behavior. In response, Indigenous women worried about the missionaries. They feared losing power and freedom in their communities. By 1649, both the Jesuit mission and the Huron society were almost destroyed by Iroquois invasions. In 1653, the Onondaga Nation, one of the five nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, offered peace to New France. A group of Jesuits, led by Simon Le Moyne, set up Sainte Marie de Ganentaa in 1656. The Jesuits had to leave the mission by 1658 when fighting with the Iroquois started again.

The rules for the Compagnie des Cent-Associés said that New France could only be Roman Catholic. This meant that Huguenots (French Protestants) faced legal limits to enter the colony. This happened when Cardinal Richelieu gave control of the colony to the company in 1627. Protestantism was then outlawed in France and all its lands overseas by the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685. Despite this, about 15,000 Protestants settled in New France. They used social or economic reasons to hide their religious background.

Huguenots were merchants from the coastal cities of Northwest France. They had a big impact on the early growth of New France, especially in Quebec and Acadia. Many people there still have Huguenot last names today. Huguenots were known for their large trading and communication network. This network spread throughout France and most of its colonies. It also traded with the Dutch Republic and the Kingdom of England, two of France's main rivals, who were also Protestant nations.

At first, King Henri IV saw Protestants as an important minority in France. He allowed them some religious freedom. After some conflicts in France, the Huguenots were seen as not "faithful servants of the king." Their trading power was taken away, their network was broken up, and the government started persecuting them in France and New France. In 1661, Louis XVI became king and started many anti-Protestant rules across the French Empire. Under these new rules, Protestant children were forced to convert to Catholicism. The government took direct control over trade routes that Huguenots used to control. Protestant communities in New France (especially Quebec and Acadia) were seen as threats. It was thought they might side with English Protestants who were competing in the same areas and trades. Eventually, Protestants were banned from settling in New France. Existing ones were only allowed to "summer" in the colonies, not "winter" there.

Political Divisions of New France

Before the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, New France was divided into four colonies:

- Acadie

- Canada

- Illinois Country (before 1717)

- Louisiana

- Illinois Country (after 1717)

- Terre-Neuve

The Treaty of Utrecht meant France gave up its claims to mainland Acadia, Hudson Bay, and Newfoundland. France then created the colony of Île Royale, now called Cape Breton Island. Here, the French built the Fortress of Louisbourg.

Acadia had a difficult history. The Great Upheaval is remembered every year on July 28. The descendants of these people are now spread out. They live in the Maritime Provinces of Canada, in Maine and Louisiana in the United States. Smaller groups are in Chéticamp, Nova Scotia, and the Magdalen Islands.

Images for kids

-

Governor Frontenac performing a tribal dance with Indigenous allies

-

Engraving depicting Adam Dollard with a keg of gunpowder above his head, during the Battle of Long Sault

-

Map showing British territorial gains following the Treaty of Paris in pink, and Spanish territorial gains after the Treaty of Fontainebleau in yellow

See also

In Spanish: Nueva Francia para niños

In Spanish: Nueva Francia para niños

- French Colonial Historic District

- Slavery in New France

- Timeline of New France history