Louis XV facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Louis XV |

|

|---|---|

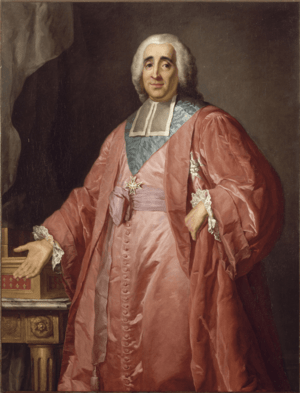

Portrait by Louis-Michel van Loo, c. 1763

|

|

| King of France (more...) | |

| Reign | 1 September 1715 – 10 May 1774 |

| Coronation | 25 October 1722 Reims Cathedral |

| Predecessor | Louis XIV |

| Successor | Louis XVI |

| Regent | Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1715–1723) |

| Chief ministers |

See list

Guillaume Dubois

(1715–1723) Louis Henri I, Prince of Condé (1723–1726) André-Hercule de Fleury (1726–1743) The Duke of Choiseul (1758–1770) |

| Born | 15 February 1710 Palace of Versailles, France |

| Died | 10 May 1774 (aged 64) Palace of Versailles, France |

| Burial | 12 May 1774 Royal Basilica, Saint Denis, France |

| Spouse | |

| Issue among others... |

|

| House | Bourbon |

| Father | Louis, Duke of Burgundy |

| Mother | Marie Adélaïde of Savoy |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

Louis XV (born February 15, 1710 – died May 10, 1774) was the King of France for nearly 59 years, from 1715 until his death. He was known as Louis the Beloved (le Bien-Aimé). He became king at just five years old, after his great-grandfather Louis XIV passed away.

For the first eight years of his rule, France was governed by his grand-uncle, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who acted as Regent. After Philippe's death, Cardinal Fleury became the chief minister and guided the kingdom until 1743. After Fleury, Louis XV took full control.

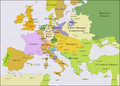

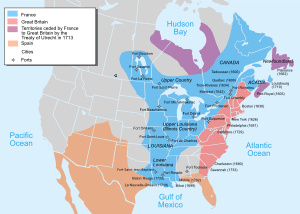

His long reign was the second longest in French history. During his time as king, France gained the territories of Duchy of Lorraine and Corsican Republic. However, France also lost New France in North America to Great Britain and Spain after the difficult Seven Years' War. Many historians believe his reign had problems, including corruption and costly wars that didn't bring much benefit. These issues contributed to the French Revolution that happened after his grandson, Louis XVI, became king.

Contents

- Early Life and Becoming King (1710–1723)

- Rule with the Duke of Bourbon (1723–1726)

- Rule with Cardinal de Fleury (1726–1743)

- Personal Rule (1743–1757)

- Rule with the Duke de Choiseul (1758–1770)

- Last Years of Rule (1770–1774)

- Personality and Legacy

- Patron of Arts and Architecture

- King and the Enlightenment

- Legacy

- Arms

- Issue

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Becoming King (1710–1723)

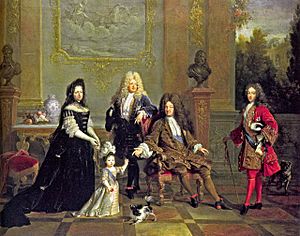

Louis XV was the great-grandson of King Louis XIV. He was born at the Palace of Versailles on February 15, 1710. At birth, he was called the Duke of Anjou. It seemed unlikely he would become king because there were many others ahead of him in line. However, a series of illnesses tragically changed everything.

In 1711, his grandfather, the Grand Dauphin, died. Then, in 1712, Louis's mother, Marie Adélaïde, and his father, the Duke of Burgundy, both died from measles. This made Louis's older brother the new Dauphin (heir to the throne). But just weeks later, both Louis and his brother caught measles. Doctors treated them with bloodletting, a common but often dangerous practice at the time. Sadly, Louis's older brother died.

Louis's governess, Madame de Ventadour, bravely hid him and stopped the doctors from bleeding him. This saved his life. When Louis XIV died on September 1, 1715, five-year-old Louis unexpectedly became King Louis XV.

The Regency Period

Since Louis was so young, France needed a regent to rule for him. This role usually went to the king's closest adult relative. Louis's great-uncle, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, became the Regent. Louis XIV had not fully trusted Philippe, so he tried to limit the Regent's power in his will.

However, Philippe convinced the Parlement of Paris (a court of nobles) to cancel parts of the will. In return, he gave the Parlement back its droit de remonstrance, which was the right to challenge the king's decisions. This agreement later caused problems between the Parlement and the King.

In 1715, the young King moved from Versailles to Paris. He began his royal duties, attending important meetings. When he was seven, he was placed under the care of François de Villeroy, who taught him about court manners and how to greet important visitors. One famous visitor was Peter the Great, the Tsar of Russia, who surprised everyone by picking up the young King and giving him a kiss! Louis also learned to ride horses and hunt, which he loved.

His tutor, André-Hercule de Fleury, taught him many subjects like Latin, history, and science. Louis loved learning and later supported new departments in physics and mechanics. He also attended meetings of the Regency Council, learning about government.

During the Regency, there was an economic crisis. A Scottish banker named John Law tried to fix France's finances by creating a bank that issued paper money and encouraging investment in a company colonizing Louisiana. The plan failed, causing many people to lose money and making them distrust paper money.

France also went to war with Spain but quickly made peace. There was a plan to marry Louis to a seven-year-old Spanish princess, Mariana Victoria of Spain, but this was later called off. The Regency period was generally peaceful, and new ideas from the Age of Enlightenment began to spread.

Rule with the Duke of Bourbon (1723–1726)

As Louis approached his 13th birthday, he moved back to Versailles. On October 25, 1722, he was crowned King at Reims Cathedral. On February 15, 1723, Louis was declared an adult, officially ending the Regency. Philippe II continued as Prime Minister but died later that year. Louis XV then appointed his cousin, Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon, as the new Prime Minister.

Marriage and Family Life

One of the Duke of Bourbon's main goals was to find a queen for Louis to ensure the royal family would continue. They chose 21-year-old Marie Leszczyńska, the daughter of the former King of Poland, Stanisław Leszczyński.

The wedding took place in September 1725. Louis was 15, and Marie was 22. They had ten children together, eight girls and two boys. Their elder son, Louis, born in 1729, survived childhood and was celebrated as the heir to the throne. He later became the father of the future King Louis XVI.

Queen Marie was a quiet and religious person. She enjoyed music and reading. After 1737, she and the King no longer shared a bed. She was very sad when her son, the Dauphin, died in 1765, and she passed away in 1768.

Religious Conflicts

An early challenge in Louis XV's reign was a conflict within the Catholic Church over a papal order called Unigenitus. This order condemned Jansenism, a Catholic teaching. Many important people in France, including members of the Parlement, supported Jansenism.

Despite protests, Cardinal Fleury convinced the King to make Unigenitus a law in France. The government and church then took strong actions against those who disagreed. This caused ongoing religious disagreements throughout Louis's reign.

The Duke of Bourbon and Cardinal Fleury also had a rivalry. The King preferred Fleury's advice, and eventually, Louis dismissed the Duke of Bourbon, making Fleury his main advisor.

Rule with Cardinal de Fleury (1726–1743)

From 1726 until his death in 1743, Cardinal Fleury was the real power behind the throne. He made most of the decisions, and the King trusted him. This period was mostly peaceful and prosperous for France. However, there was growing opposition from the nobles in the Parlements, who felt their power was being reduced. Fleury also did not focus enough on building up the French Navy, which would be a problem later.

Fleury's government was stable. He kept the same ministers for many years, which was unusual. His finance minister, Philibert Orry, helped reduce the national debt and made the tax system fairer. For a short time, Orry even managed to balance the royal budget.

Fleury's government also helped trade grow. They improved transportation by building canals and a national road network. By the mid-1700s, France had one of the best road systems in the world. French trade with other countries also increased significantly.

The government continued to suppress religious dissent, especially against Jansenists. Many members of the Parlements who opposed the Unigenitus order were dismissed.

Foreign Policy and the War of the Polish Succession

Fleury wanted to keep peace in Europe. He worked to maintain alliances with Great Britain and rebuild ties with Spain. However, new powers like Russia and Austria were growing stronger.

In 1732, a conflict arose over who would be the next King of Poland. The Queen of France's father, Stanislaus I, was a candidate. Russia, Prussia, and Austria secretly agreed to support another candidate. When the Polish king died, this led to the War of the Polish Succession.

France declared war on Austria in 1733. French armies occupied Lorraine and captured Milan. However, Fleury was less active in helping Stanislaus in Poland. Stanislaus was forced to flee.

To end the war, Fleury negotiated a clever solution. Francis III, Duke of Lorraine, gave up Lorraine. In return, he married Maria Theresa, who was set to inherit the Austrian lands. Stanislaus became the Duke of Lorraine, and after his death, Lorraine would become part of France. This happened in 1766.

Fleury also helped end a war between the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire. These successes made Louis XV's reputation very strong in Europe.

War of the Austrian Succession

In 1740, Emperor Charles VI died, and his daughter Maria Theresa was set to take over. Louis XV initially wanted to stay out of the conflict. However, France's allies saw a chance to gain land from the Austrian Empire. Frederick the Great of Prussia invaded Austrian territory, starting the War of the Austrian Succession.

Fleury's general, Charles Louis Auguste Fouquet, duc de Belle-Isle, made an alliance with Prussia against Austria, and the war began. French and Bavarian armies had some early successes. But in 1742, Prussia left the alliance, and Britain joined Austria's side. The war turned against France. Cardinal Fleury died in 1743, and Louis XV began to rule alone.

The war continued, with France facing many enemies. However, in 1744, the French position improved when Frederick the Great rejoined the war on France's side. Louis XV personally led his armies in the Netherlands. At the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745, Louis witnessed a French victory. He told his son, "You see what a victory costs. The blood of our enemies is still the blood of men. The true glory is to spare it."

French forces continued to win battles and occupied the Austrian Netherlands (modern-day Belgium). In 1748, Louis proposed a peace conference. Despite French victories, Louis was eager for peace because the naval war with Britain was very expensive.

In the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Louis surprisingly agreed to return all the territories France had conquered. This decision made many French people unhappy, as they felt France had gained little from the costly war. Louis believed it was better to avoid future conflicts and focus on France's prosperity.

Personal Rule (1743–1757)

After Fleury's death, Louis XV decided to rule without a prime minister. His main ministers were Jean Baptiste de Machault D'Arnouville for finance and Comte d'Argenson for the army.

Financial Reforms and Resistance

After the war, Louis wanted to reduce France's debt and update the tax system. His finance minister, D'Arnouville, proposed new taxes. One important change was the vingtième, a 5% tax on everyone's income, including nobles and the church, who had often been exempt.

This new tax faced strong opposition from the nobility and the church. The Parlement of Paris, a powerful court of nobles, resisted the tax. Louis insisted, and the Parlement reluctantly agreed. However, resistance continued in the provinces. The King had to take strong actions, like closing down some Parlements, to enforce his will.

The King's plan to tax the church also failed. The church refused to declare its income, and Louis eventually agreed to accept a voluntary donation instead of a tax. This showed the King's difficulty in enforcing his authority over powerful groups.

The Seven Years' War Begins

The peace after the War of the Austrian Succession lasted only seven years. Conflict began again between Britain and France, especially in their colonies in North America. French colonists were greatly outnumbered by British colonists.

In 1754, fighting broke out in North America, known as the French and Indian War. Britain began seizing French merchant ships. In 1756, Frederick the Great of Prussia allied with Britain. Louis XV responded by forming a defensive alliance with Austria, a major shift in France's foreign policy.

France declared war on Great Britain in June 1756. France had some early successes, like capturing Minorca. However, France's best general had died, and the new commanders often disagreed.

In November 1757, Frederick the Great defeated the French army at the Battle of Rossbach. British naval power also prevented France from sending help to its colonies. Britain captured French islands in the West Indies and took Quebec and Montreal in Canada. By 1760, French rule in Canada ended.

Assassination Attempt

On January 5, 1757, a man named Robert-François Damiens attacked the King with a knife at Versailles. The King was injured but quickly recovered. Damiens was captured, tortured, and executed. The attack deeply affected Louis, making him more withdrawn. After this event, the King invited his son, the Dauphin, to attend all Royal Council meetings.

Rebellion of the Parlements

The Parlements, which were courts of nobles in different regions of France, continued to challenge the King's authority. They often refused to follow royal decrees or collect new taxes. This caused the justice system to slow down.

In 1761, the Parlement of Normandy protested, claiming they had the right to collect taxes. The King rejected this, banishing some members. For the rest of his reign, the Parlements continued to resist the King's new taxes and authority. This growing conflict between the King and the Parlements was an important cause of the French Revolution.

Changes in Government

Comte d'Argenson served as War Minister from 1743. He helped create France's first engineering school and rebuilt the military. Jean Baptiste de Machault D'Arnouville was Finance Controller. He created the unpopular "Vingtieme" tax and tried to free grain prices, which later caused problems.

In 1757, the King suddenly dismissed both d'Arnouville and d'Argenson. He blamed them for not preventing the assassination attempt and for displeasing his influential friend, Madame de Pompadour.

Rule with the Duke de Choiseul (1758–1770)

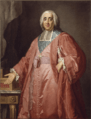

In 1758, Louis appointed the Duke de Choiseul as his foreign affairs minister, on the recommendation of Madame de Pompadour. Choiseul soon became the most powerful minister, also taking charge of the War and Navy departments. He was a leader of the philosophe group, who wanted to ease tensions with the Parlements.

Choiseul's biggest achievement was modernizing the French military. He improved training, standardized artillery, and adopted new tactics. He also launched a major shipbuilding program to rebuild the French Navy, which had been weakened in the Seven Years' War.

Suppression of the Jesuits (1764)

In 1764, Louis XV decided to suppress the Jesuit Order in France. This decision was influenced by the Parlements, Madame de Pompadour, and Choiseul. The Jesuits had many schools and were seen as too independent from the King's authority.

The campaign against the Jesuits divided the royal family. The King's son and daughters supported the Jesuits, while Madame de Pompadour wanted them gone. The Jesuits left France and were welcomed in other countries. Their departure weakened the church in France and showed how the King was influenced by the Parlements.

Continued Resistance from Parlements

Under Choiseul, the Parlements in several provinces continued to resist the King's authority and new taxes. For example, the Parlement of Franche-Comté refused to collect the vingtieme tax. The King responded by dismissing their leaders.

The Parlement of Normandy also protested, claiming the King was ignoring his oath to the nation. Louis XV firmly stated that his power came from God alone, not the nation. This conflict between the King's absolute power and the Parlements' desire for more influence continued to grow.

Financial Challenges

The long war drained France's treasury. Choiseul's finance minister, Étienne de Silhouette, tried to raise money by taxing luxury goods. These taxes were very unpopular with the wealthy, and Silhouette was dismissed after only eight months.

The next finance minister, Henri Bertin, tried to tax more classes of people and survey the wealth of the nobility. Again, the Parlements rebelled and refused to collect the new taxes. The King had to withdraw the decrees, and the national debt remained a problem.

End of the Seven Years' War

The war with Great Britain continued. In 1761, France, Spain, and other Bourbon-ruled countries signed a "Family Pact" to support each other. Choiseul worked to rebuild the French Navy and planned for a new war with Britain.

However, French military efforts were not enough. British naval power was too strong, and France lost more colonies. Choiseul decided it was time to end the war. The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763. France gave up most of its territories in Canada but got back some valuable sugar islands in the West Indies. The Ohio Valley and lands west of the Mississippi River were given to Spain.

Personal Losses

In 1764, Madame de Pompadour, the King's influential friend, died from pneumonia. The King was deeply saddened. In 1765, his son and heir, the Dauphin Louis, died from tuberculosis. This was a great personal tragedy for the King, who fell into a deep sadness. His wife, Queen Marie, also passed away in 1768.

The King's Authority Challenged

In 1766, the Parlement of Brittany again challenged the King's right to collect taxes. They claimed the King had taken an oath to the nation. Louis XV strongly disagreed, stating his power came only from God. He appeared before the Parlement of Paris and declared, "It is in my person alone that sovereign power resides...To me alone belongs the legislative power, without dependence and without sharing...The public order emanates entirely from me." This strong speech, known as "the flagellation," showed the King's determination to maintain his absolute power.

Madame du Barry

After Madame de Pompadour's death, Jeanne Bécu, the comtesse du Barry, became the King's new friend. She was much younger than the King. Her presence at court caused a scandal among the older nobility and even with the young Marie Antoinette, who married the Dauphin in 1770. Madame du Barry was often criticized and became a target of negative pamphlets. Despite this, the King kept her close until his final days.

France Grows Larger

France's borders expanded with two new additions. The Duchy of Lorraine officially became part of France in 1766, after the death of the King's father-in-law, Stanislaus. Corsica was also added to France. The island had been controlled by rebels, and France sent troops to take control. In 1769, the Corsican rebels were defeated, and Corsica became a French province in 1770.

Economy and Rumors

Two economic thinkers, François Quesnay and Jacques Claude Marie Vincent de Gournay, greatly influenced the King. They believed in less government control over the economy, using the phrase laissez faire, laissez passer ("let it be done, let it pass").

Following their ideas, the King's finance minister allowed grain to be traded freely without taxes. This helped increase trade and lower prices in good years. However, during years with poor harvests, prices went up. This led to rumors of a "Starvation Pact," a false belief that the government was trying to starve the poor. These rumors contributed to the unrest that led to the French Revolution.

Preparing for War Again

The Duc de Choiseul worked hard to prepare France for another war with Britain. He created new military schools and rebuilt the French Navy. By 1772, France had a strong fleet. He also formed the "Family Pact," an alliance with other Bourbon-ruled countries like Spain.

Choiseul was so focused on Britain that he neglected other parts of Europe. France did not have ambassadors in places like Poland or Russia, and he did not protest when Russia and Prussia divided Poland.

Choiseul's Dismissal

In 1770, a conflict between Britain and Spain over the Falkland Islands led to Choiseul's downfall. Both sides prepared for war. At the same time, the Parlement of Brittany again refused to recognize the King's power to tax.

The King wanted to avoid war and settle the Falklands crisis peacefully. He also felt that Choiseul's ideas were too different from his own beliefs about religion and royal authority. On December 24, 1770, Louis XV abruptly dismissed Choiseul from his post.

Last Years of Rule (1770–1774)

After Choiseul's dismissal, Louis XV put a group of three conservative ministers in charge, known as "The Triumvirate." They were led by Chancellor René de Maupeou, with Abbot Terray for finance and the Duc d'Aiguillon for foreign affairs and war.

Controlling the Parlements

Maupeou's main goal was to bring the rebellious Parlements under control. Many Parlement members were on strike, refusing to do their jobs. In January 1771, the King's agents seized their positions and ordered them to leave Paris.

Then, the King replaced the regional Parlements with new high courts. He also abolished the high fees that the Parlements charged for legal cases, making justice free. This allowed the government to pass new laws and taxes without opposition. However, after Louis XV's death, the nobility demanded that the regional Parlements be brought back.

Financial Improvements

Abbot Terray, the finance minister, was very effective at collecting taxes. He worked to ensure taxes were collected fairly and consistently across all regions. When he started, the government had a large debt. By 1774, he had increased revenues and significantly reduced the debt. He also brought back government control over grain prices, which continued to be a sensitive issue.

Foreign Affairs

After Choiseul, Louis XV worked to avoid war and settle disputes peacefully. He encouraged Spain to resolve the Falkland Islands crisis. France had neglected its relationships with other European countries. For example, Russia and Prussia divided Poland without any protest from France.

However, Louis XV did support Gustav III of Sweden, helping him become King of Sweden. This prevented Sweden from being divided by Russia and Prussia.

Life at Versailles

In his final years, the court at Versailles continued its grand traditions. Marie Antoinette, the future queen, did not hide her dislike for Madame du Barry. The King built luxurious rooms for Madame du Barry and continued his grand construction projects, including the opera theater at Versailles and the new Place Louis XV (now Place de la Concorde) in Paris.

Death

On April 26, 1774, the King felt ill while at the Petit Trianon. He was brought back to Versailles. Doctors diagnosed him with smallpox, a dangerous disease. His family, including the Dauphin and Marie Antoinette, were asked to leave to avoid catching it. Madame du Barry stayed with him.

As his condition worsened, the King prepared for his final rites. He asked Madame du Barry to leave, saying he owed it to God and his people. Louis XV died on May 10, 1774, at 3:15 in the morning.

Personality and Legacy

People who knew Louis XV described him in different ways. He was seen as intelligent, with a good memory, and a kind father. He was interested in science but was also very modest, which some saw as a weakness. He often hesitated to make decisions on his own, relying on others for advice.

He was also known for being very shy and quiet, finding it hard to talk to people. Another trait was his love for secrecy. Some said he worked hard to hide his true thoughts and feelings. One person wrote that he spoke about government matters as if someone else was in charge.

The "After Us the Deluge" Legend

The most famous quote attributed to Louis XV is "After us, the deluge" (Après nous, le déluge). This is often thought to mean he didn't care about France's future problems. However, the quote was made in 1757, a year of military defeat and an assassination attempt. The "deluge" he referred to was likely the predicted return of Halley's Comet, which was believed to have caused the biblical flood. The King was an amateur astronomer, and his remark was probably a dark joke about the difficult times.

Patron of Arts and Architecture

Louis XV was a major supporter of architecture. He spent more money on buildings than Louis XIV. His main architect, Ange-Jacques Gabriel, designed famous buildings like the Ecole Militaire, the Place de la Concorde, and the Petit Trianon at Versailles. Louis also started the construction of the Church of Saint-Geneviève (now the Pantheon). His workshops produced beautiful furniture, porcelain, and tapestries in the Louis XV Style, which were popular across Europe.

The King and his family also loved music. The young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart even dedicated two sonatas to the King's daughter. Jean Philippe Rameau was a famous court composer during his reign.

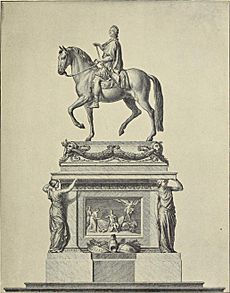

Louis XV, guided by Madame de Pompadour, was also a very important art patron. He commissioned famous artists like François Boucher and supported sculptors like Edmé Bouchardon, who created a large statue of Louis XV in Paris.

King and the Enlightenment

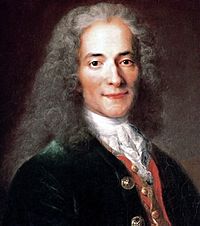

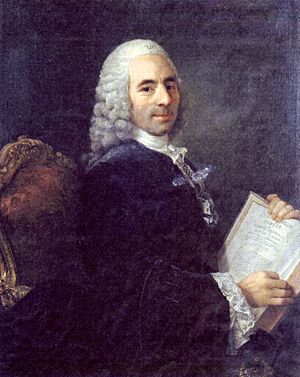

The Age of Enlightenment, a period of new ideas and thinking, grew stronger during Louis XV's reign. Important thinkers like Denis Diderot, Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau published their works. These writings questioned traditional ideas about government, economics, and society.

At first, the King's censors allowed these publications. For example, the first volume of Diderot's Encyclopédie was approved because it seemed like a science collection. But as the Encyclopédie included more authors and challenged church doctrines, the government banned it in 1759.

Rousseau, another influential thinker, wrote about political and economic equality. His ideas, developed during Louis XV's reign, later influenced the French Revolution. Voltaire, a famous writer, initially had a good relationship with the court but later moved away. He supported the King's efforts to reform the Parlements and tax system, but was disappointed by the lack of further changes.

Legacy

For much of his life, Louis XV was seen as a national hero. A statue of him was built in Paris to celebrate his role as a peacemaker. However, after France's defeat in the Seven Years' War, the statue was seen differently. It was later torn down during the French Revolution.

Many historians agree that Louis XV's decisions weakened France's power and finances. His rule contributed to the problems that led to the French Revolution 15 years after his death. Some describe his reign as a period of "stagnation" with lost wars and conflicts between the King and the Parlements.

Historians note that Louis XV was handsome, intelligent, and a good hunter, but he often disappointed the public. People felt he did not maintain the sacred image of the monarchy. His personal life and the scandals surrounding it also damaged the public's trust in the monarchy.

The financial strain from wars and royal spending, along with public dissatisfaction, contributed to the unrest that led to the French Revolution. Louis XV failed to solve these financial problems, partly because he couldn't unite the different groups in his government.

Some scholars have defended Louis XV, arguing that his negative reputation was created later to justify the French Revolution. They point out that France was not invaded during his reign, and he was initially popular. His attempts to control the Parlements and reform the tax system were seen by some as efforts to prevent revolution. However, his successor, Louis XVI, reversed many of these policies.

While France reached a high point in culture and art under Louis XV, he is often blamed for diplomatic, military, and economic setbacks. His reign was marked by unstable ministers, and his reputation suffered due to military failures and colonial losses.

Arms

|

|

Issue

- Louise Élisabeth (August 14, 1727 – December 6, 1759), Duchess of Parma, had children.

- Anne Henriette (August 14, 1727 – February 10, 1752).

- Marie-Louise (July 28, 1728 – February 19, 1733).

- Louis, Dauphin of France (September 4, 1729 – December 20, 1765), married Infanta Maria Teresa Rafaela of Spain and had children, then married Duchess Marie-Josèphe of Saxony and had children, including Louis XVI.

- Philippe of France, Duke of Anjou (August 30, 1730 – April 17, 1733).

- Marie Adélaïde (March 23, 1732 – February 27, 1800).

- Victoire Louise Marie Thérèse (May 11, 1733 – June 7, 1799).

- Sophie Philippine Élisabeth Justine (July 27, 1734 – March 3, 1782).

- Marie Thérèse Félicité (May 16, 1736 – September 28, 1744).

- Louise Marie (July 15, 1737 – December 23, 1787).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Luis XV de Francia para niños

In Spanish: Luis XV de Francia para niños

- Louis XV Style

- Louis XV furniture

- Rocaille

- List of French monarchs

- Persecution of Huguenots under Louis XV

- Kingdom of Navarre

- Cabriole leg

- Étienne François, Duc de Choiseul

- Suppression of the Jesuits

- Louis heel, a shoe heel shape named after Louis XV.

- Mesdames de France

- Outline of France

- List of famous big game hunters

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |