Voltaire facts for kids

François-Marie Arouet (born November 21, 1694 – died May 30, 1778) was a famous French writer and thinker. He is better known by his pen name, Voltaire. He lived during the Age of Enlightenment, a time when new ideas about freedom and reason were popular.

Voltaire was known for his sharp wit and for speaking out against unfairness. He criticized the Roman Catholic Church and slavery. He strongly believed in freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the idea of keeping the church and government separate.

He wrote many different kinds of works, including plays, poems, novels, and essays. Voltaire wrote over 20,000 letters and 2,000 books. He was one of the first writers to become famous and successful around the world. He often faced problems with strict censorship laws in France. His writings made fun of intolerance and old-fashioned ideas. His most famous work is Candide, a short novel that criticizes many ideas of his time.

Voltaire's Early Life

François-Marie Arouet was born in Paris. He was the youngest of five children. His father was a lawyer. Voltaire went to school with the Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand. There, he learned Latin, theology, and public speaking. Later, he became good at speaking Italian, Spanish, and English.

After school, Voltaire decided he wanted to be a writer. His father wanted him to be a lawyer. Voltaire pretended to work as a legal assistant in Paris. But he spent most of his time writing poetry. When his father found out, he sent Voltaire to study law in Caen. However, Voltaire kept writing essays and historical studies.

His cleverness made him popular with some rich families. In 1713, he got a job as a secretary for the French ambassador in the Netherlands. There, Voltaire fell in love with a French Protestant refugee. Their relationship was seen as scandalous. Voltaire was forced to return to France.

Voltaire often had trouble with the government because he criticized it. He was sent to prison twice. Once, he was temporarily sent away to England. His first play, Œdipe, was performed in 1718. It was a big success and made him famous.

He strongly argued for religious tolerance and freedom of thought. He wanted to end the power of priests and kings. He supported a government where a king rules, but people's rights are protected by a constitution.

Voltaire started using the name Voltaire in 1718. This was after he was released from prison. The name is a mix of letters from his last name, Arouet. It also sounds like words meaning "speed" and "daring" in French. He used many different pen names during his life.

Voltaire's Career as a Writer

Early Writings

Voltaire's next play, Artémire, was not successful in 1720. He then started writing an epic poem about Henry IV of France. He could not get permission to publish it in France. So, in 1722, he went to find a publisher outside of France.

He found a publisher in The Hague, Netherlands. Voltaire was impressed by how open and tolerant Dutch society was. When he returned to France, he found another publisher. This publisher agreed to print La Henriade secretly. The poem was a huge success.

Time in Great Britain

In 1726, a rich nobleman insulted Voltaire. Voltaire challenged him to a duel. But the nobleman's family had Voltaire arrested. He was sent to the Bastille prison without a trial. Fearing he would be imprisoned forever, Voltaire asked to be sent to England instead. The French government agreed.

In England, Voltaire met many important people. His time there greatly changed his ideas. He was interested in Britain's government, which had a king but also protected people's rights. This was different from the absolute power of the French king. He also admired Britain's greater freedom of speech and religion.

He was influenced by English writers, especially William Shakespeare. Voltaire helped introduce Shakespeare's plays to Europe. He also became interested in the ideas of Isaac Newton, a famous scientist.

After two and a half years, Voltaire returned to France. He became very rich by investing money wisely. In 1732, his play Zaïre was a success. He also published essays praising British government and freedom. These essays were published in France in 1734 as Lettres philosophiques. They caused a big scandal. The book was burned and banned. Voltaire had to leave Paris again.

Life at Château de Cirey

Voltaire learned to avoid direct conflict with the authorities. He continued to write plays and study science and history. He was still very inspired by Isaac Newton's ideas from his time in England. Voltaire believed strongly in Newton's theories. He even did experiments on light. He helped spread the famous story of Newton and the falling apple.

Voltaire's book Elements of the Philosophy of Newton made Newton's ideas easier for many people to understand. This book helped Newton's theories become accepted in France.

Voltaire also studied history. He wrote about great people who helped civilization. His poem La Henriade praised King Henry IV of France for trying to end religious wars. He also wrote a historical novel about King Charles XII of Sweden. These works showed Voltaire's growing criticism of intolerance and old religions. Voltaire and his friend, the Marquise, also studied philosophy. They looked at the Bible and questioned some of its content. Voltaire's views on religion led him to believe in the separation of church and state and religious freedom.

In 1736, Frederick the Great, who was then a prince, started writing letters to Voltaire. Voltaire later visited Frederick in Prussia several times. In 1743, the French government sent Voltaire to Frederick's court. He was sent to find out Frederick's military plans.

Time in Prussia

After his friend the Marquise died in 1749, Voltaire moved to Prussia. He was invited by Frederick the Great, who was now king. Frederick made him a special assistant and gave him a good salary. Voltaire lived in palaces like Sanssouci.

At first, things went well for Voltaire. In 1751, he wrote Micromégas, a science fiction story. But his relationship with Frederick got worse. Voltaire had arguments with other important people in Prussia. Frederick became angry and ordered Voltaire's writings to be burned. In 1752, Voltaire decided to leave Prussia. He had a difficult journey back to France. Frederick's agents even stopped him and searched his belongings.

Life in Geneva and Ferney

Voltaire was banned from Paris by King Louis XV of France. So, in 1755, he bought a large estate near Geneva, Switzerland. At first, he was welcomed. But Geneva had strict laws against plays. Also, a poem he wrote, The Maid of Orleans, was published without his permission. This made his relationship with the people of Geneva difficult.

In 1758, he bought an even bigger estate in Ferney, France, near the Swiss border. He lived there for most of the next 20 years. Many important guests visited him there. In 1759, he published Candide, ou l'Optimisme. This book makes fun of the idea that everything happens for the best. It is still his most famous work.

In 1764, he published Dictionnaire philosophique. This book contains articles about Christian history and beliefs. From 1762, Voltaire became famous for defending people who were treated unfairly. One famous case was Jean Calas, a Protestant merchant. Calas was wrongly killed because people thought he murdered his son. Voltaire fought to prove Calas's innocence and succeeded in 1765.

Voltaire joined Freemasonry a month before he died. He attended a meeting in Paris.

Death and Burial

In February 1778, Voltaire returned to Paris after 25 years. He wanted to see his new play, Irene. The journey was too much for the 83-year-old. He thought he was going to die. But he recovered and saw his play performed. The audience treated him like a hero.

He became ill again and died on May 30, 1778. Because he had criticized the Church, he was not allowed a Christian burial in Paris. But his friends secretly buried his body in a church in Champagne. His heart and brain were preserved separately.

In 1791, the French government saw Voltaire as a hero of the French Revolution. They moved his remains to the Panthéon in Paris. About a million people attended the procession.

Voltaire's Important Writings

History Books

Voltaire greatly influenced how history was written. He showed new ways to understand the past.

His most famous history books are History of Charles XII (1731), The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756). He focused on people's daily lives, social history, and achievements in arts and science. He looked at world history in a global way, not just from one country's viewpoint. He was the first to try to write a history of the world without religious ideas. He focused on economics, culture, and politics.

Voltaire believed that historians should look for more details and facts. They should pay attention to customs, laws, and trade. He helped history writing move away from just focusing on great men or wars.

Poetry

Voltaire showed a talent for writing poetry from a young age. His first published work was poetry. He wrote two long epic poems. One was Henriade, which was very popular. It made French King Henry IV a hero for trying to bring religious tolerance. The other, La Pucelle, was a funny poem about Joan of Arc.

Prose Works

Many of Voltaire's prose works were written to argue against ideas he disagreed with. Candide attacks the idea that everything is always for the best. Zadig questions common ideas about right and wrong. Some of his works even made fun of the Bible. In these writings, Voltaire's clever and simple style is clear. Candide is a great example of his writing.

Voltaire also helped create philosophical science fiction. This can be seen in his stories Micromégas and "Plato's Dream".

In his writings, especially his private letters, Voltaire often urged people to "crush the infamous" (écrasez l'infâme). This phrase referred to the unfair power of kings and religious leaders. It also meant fighting against superstition and intolerance. He saw these problems in his own life, with his books being burned and people like Jean Calas being cruelly treated. He famously said, "Superstition sets the whole world in flames; philosophy quenches them."

A famous quote often linked to Voltaire is: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." These words were actually written by Evelyn Beatrice Hall in 1906. She wrote them to summarize Voltaire's attitude.

Voltaire's first major philosophical work against "the infamous" was Traité sur la tolérance. This book exposed the unfairness of the Calas affair. It also showed how other religions and times had practiced tolerance. In his Dictionnaire philosophique, he wrote about the human origins of religious beliefs. He also wrote about the cruel behavior of religious and political groups.

Letters

Voltaire wrote an enormous number of letters, over 20,000 in total. These letters show his wit, kindness, and deep thoughts.

In his letters with Catherine the Great, he discussed democracy. He wrote that great things are usually done by one strong person, not by many people.

Voltaire's Views on Religion and Philosophy

Like other thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment, Voltaire was a deist. This means he believed in God, but thought God created the universe and then let it run on its own. He questioned traditional religious beliefs. He said, "It is perfectly clear to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is not a matter of faith, but of reason."

In a 1763 essay, Voltaire supported being tolerant of all religions and people. He said, "We should regard all men as our brothers." He believed that people of all backgrounds, including Turks, Chinese, and Jews, are children of the same God.

Views on Christianity

Voltaire's writings about Christianity were often critical. In his Dictionnaire philosophique, he spread some myths about the early Church. He also suggested that the Christian religion was "the most ridiculous, the most absurd and the most bloody religion which has ever infected this world." He wished he could help get rid of this "infamous superstition."

Voltaire's opinion of the Bible was mixed. His critical views made the Jesuits angry. The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, a Christian, called Voltaire an "arch-scoundrel."

However, Voltaire also recognized good things in Christianity. He wrote that there is "nothing greater on earth than the sacrifice of youth and beauty... made by the gentle sex in order to work in hospitals for the relief of human misery." But his dislike of religion grew over time. He attacked not just the Church's power but also its beliefs and even Jesus Christ. Voltaire's thinking can be summed up in his saying: "Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities."

Views on Judaism

Voltaire had strong negative views about Judaism. In his Dictionnaire philosophique, he described Jews as "ignorant and barbarous people." He said they had "sordid avarice" and "invincible hatred for every people by whom they are tolerated."

Some historians say Voltaire criticized Jews to criticize Christianity. Others suggest his negative views came from bad personal experiences with Jewish financiers. However, detailed studies show he was against the Bible, not against Jewish people themselves. His comments on Jewish "superstitions" were similar to his comments on Christians.

Voltaire did have a Jewish friend, Daniel de Fonseca, whom he respected. He also condemned the persecution of Jews at times. He once agreed that there are "highly intelligent and cultivated people" among Jews. He promised to change his harsh words in future editions of his dictionary, but he did not.

Views on Islam

Voltaire's views on Islam were generally negative. He found the Quran to be illogical. In a letter, he called Muhammad brutal and said his followers were based on superstition. He wrote that Muhammad was a "sublime charlatan."

In his play Fanaticism, or Mahomet the Prophet, Voltaire showed Muhammad as a character who ordered the murder of his critics. Voltaire said the play was against "the founder of a false and barbarous sect." He described Muhammad as an "impostor" and a "hypocrite."

However, as Voltaire learned more about Islam, his opinion became slightly more positive. In his Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations, he called Muhammad a "poet" and a "legislator" who changed a large part of the world. He noted similarities between Arabs and ancient Hebrews. He also said that Muhammad's civil laws were good and his beliefs were admirable.

Views on Hinduism

Voltaire saw Hindus as "a peaceful and innocent people." He supported animal rights and was a vegetarian. He used the ancient history of Hinduism to challenge the Bible's claims. He also thought the way Hindus treated animals was better than the actions of European imperialists.

Views on Confucianism

Voltaire was influenced by the teachings of Confucius from China. Jesuit missionaries had translated Confucian texts into European languages. Voltaire praised Confucian ethics and politics. He saw China's social system as a good example for Europe.

He believed the Chinese had "perfected moral science." He supported an economic and political system like China's. He also liked the idea of a meritocracy, where people are chosen for jobs based on their skills, not their family background.

Views on Race and Slavery

Voltaire did not believe in the biblical story of Adam and Eve. He thought that different races had separate origins. Some historians say Voltaire believed Black Africans were not fully human like white Europeans. Others suggest he used racial differences to attack religious ideas. Some also link his views to his investments in companies involved in the slave trade.

His most famous comment on slavery is in Candide. The hero is shocked to learn "at what price we eat sugar in Europe" after meeting a slave. The slave says that if all humans are cousins, as the Bible teaches, then "no one could treat their relatives more horribly." Voltaire also wrote sharply about "whites and Christians [who] buy Black people cheaply to sell them expensively in America."

In his Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire supported Montesquieu's criticism of the slave trade.

Despite some of his flaws, Voltaire was a pioneer of pluralism. He wrote, "It is time for us to give up the shameful habit of slandering all sects and insulting all nations!" He defended Native Americans and praised the Inca Empire.

Voltaire's Influence

Victor Hugo said that "To name Voltaire is to describe the entire eighteenth century." Many important people admired Voltaire. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe thought he was the greatest writer of modern times. Denis Diderot believed Voltaire's influence would last far into the future.

Napoleon said, "The more I read Voltaire the more I love him. He is a man always reasonable, never a charlatan, never a fanatic." Frederick the Great felt lucky to live in Voltaire's time and wrote to him often. In England, Voltaire's ideas influenced writers like William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft.

In Russia, Catherine the Great read Voltaire for many years. She wrote to him until his death. She even bought his library and placed it in The Hermitage.

In Paris, Voltaire is remembered for defending people like Jean Calas. He fought for justice for those wrongly accused. He also helped revise unfair laws. A Protestant minister once told Voltaire, "You seem to attack Christianity, and yet you do the work of a Christian."

Under the French Third Republic, anarchists and socialists used Voltaire's writings to fight against war and the Catholic Church. After France was freed from Nazi rule in 1944, Voltaire's 250th birthday was celebrated. He was honored as a symbol of freedom of thought and hatred of injustice.

Jorge Luis Borges said, "not to admire Voltaire is one of the many forms of stupidity." Many of the people who helped create modern America followed Voltaire's ideas.

Voltaire and Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, another famous thinker, said that Voltaire's book Letters on the English greatly helped his own thinking. Rousseau wrote to Voltaire, who was the most famous writer in France. Voltaire replied politely.

Later, Rousseau sent Voltaire a copy of his book Discourse on Inequality. Voltaire replied that he disagreed with the book. He joked, "No one has ever used so much intelligence to persuade men to be beasts."

When Voltaire reviewed Rousseau's book Emile, he called it "a jumble... with forty pages against Christianity." He predicted that Emile would be forgotten quickly.

In 1778, Voltaire received great honors in Paris. Rousseau died one month later. In 1794, Rousseau's remains were moved to the Panthéon, near Voltaire's.

King Louis XVI later said that Rousseau and Voltaire had "destroyed France."

Voltaire's Legacy

Voltaire saw problems in French society. He thought the middle class was too small. He believed the rich nobles were lazy and corrupt. He saw common people as uneducated and superstitious. He also thought the Catholic Church was too powerful and unfair. Voltaire did not trust democracy, believing it would spread the foolishness of the masses.

For a long time, Voltaire thought only a wise king could bring change. He believed it was in the king's interest to improve his people's education and well-being. But his disappointments with Frederick the Great changed his mind. This led to his famous novel Candide, ou l'Optimisme (1759). The book ends with the idea: "It is up to us to cultivate our garden." This means people should focus on improving their own lives and communities. His strongest attacks on intolerance and religious persecution came out a few years later.

Voltaire is remembered in France as a brave writer who fought for civil rights. He fought for things like the right to a fair trial and freedom of religion. He spoke out against the unfairness of the Ancien Régime, the old system in France. He especially admired the ideas and government of the Chinese philosopher Confucius.

Voltaire is also known for many famous sayings. One is: "Si Dieu n'existait pas, il faudrait l'inventer" ("If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him"). This was not a cynical remark. It was meant to argue against people who did not believe in God.

The town of Ferney, where Voltaire lived, was officially named Ferney-Voltaire in his honor in 1878. His old home is now a museum. Voltaire's library is kept in the National Library of Russia in Saint Petersburg.

Voltaire was also known for drinking a lot of coffee. Some people think the caffeine helped his creativity. His book Candide was listed as one of "The 100 Most Influential Books Ever Written."

In the 1950s, a scholar named Theodore Besterman began collecting and publishing all of Voltaire's writings. He started the Voltaire Foundation at the University of Oxford. This foundation continues to publish the Complete Works of Voltaire.

Works

Non-fiction

- Letters on the Quakers (1727)

- Letters concerning the English nation (London, 1733)

- "Le Mondain" (1736)

- Sept Discours en Vers sur l'Homme (1738)

- The Elements of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophy (1738)

- Dictionnaire philosophique (1752)

- The Sermon of the Fifty (1759)

- The Calas Affair: A Treatise on Tolerance (1762)

- Traité sur la tolérance (1763)

- Ce qui plaît aux dames (1764)

- Idées républicaines (1765)

- La Philosophie de l'histoire (1765)

- Questions sur les Miracles (1765)

- L'Ingénu (1767)

- La Princesse de Babylone (1768)

- Des singularités de la nature (1768)

- Les Dialogues d’Evhémère (1777)

History Books

- History of Charles XII, King of Sweden (1731)

- The Age of Louis XIV (1751)

- The Age of Louis XV (1746–1752)

- Annals of the Empire (Vol. I 1754, Vol. II 1754)

- Essay on Universal History, the Manners, and Spirit of Nations (1756)

- History of the Russian Empire Under Peter the Great (Vol. I 1759; Vol. II 1763)

Short Novels

- The One-eyed Street Porter, Cosi-sancta (1715)

- Micromégas (1738)

- The World as it Goes (1750)

- Memnon (1750)

- Bababec and the Fakirs (1750)

- Timon (1755)

- Plato's Dream (1756)

- The Travels of Scarmentado (1756)

- The Two Consoled Ones (1756)

- Zadig, or, Destiny (1757)

- Candide, or Optimism (1758)

- Story of a Good Brahman (1759)

- The King of Boutan (1761)

- The City of Cashmere (1760)

- An Indian Adventure (1764)

- The White and the Black (1764)

- Jeannot and Colin (1764)

- The Blind Judges of Colors (1766)

- The Princess of Babylon (1768)

- The Man with Forty Crowns (1768)

- The Letters of Amabed (1769)

- The Huron, or Pupil of Nature (1771)

- The White Bull (1772)

- An Incident of Memory (1773)

- The History of Jenni (1774)

- The Travels of Reason (1774)

- The Ears of Lord Chesterfield and Chaplain Goudman (1775)

Plays

Voltaire wrote between fifty and sixty plays. Some of them are:

- Œdipe (1718)

- Artémire (1720)

- Mariamne (1724)

- Brutus (1730)

- Éryphile (1732)

- Zaïre (1732)

- Alzire, ou les Américains (1736)

- Zulima (1740)

- Mahomet (1741)

- Mérope (1743)

- La princesse de Navarre (1745)

- Sémiramis (1748)

- Nanine (1749)

- L'Orphelin de la Chine (1755)

- Socrate (published 1759)

- La Femme qui a Raison (1759)

- Tancrède (1760)

- Don Pèdre, roi de Castille (1774)

- Sophonisbe (1774)

- Irène (1778)

- Agathocle (1779)

Collected Works

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, A. Beuchot (ed.). 72 vols. (1829–1840)

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, Louis E.D. Moland and G. Bengesco (eds.). 52 vols. (1877–1885)

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, Theodore Besterman, et al. (eds.). 144 vols. (1968–2018)

Images for kids

-

Voltaire was held in the Bastille prison from May 1717 to April 1718.

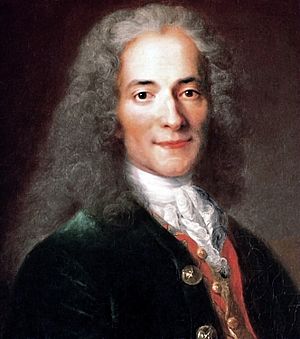

-

Pastel by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1735.

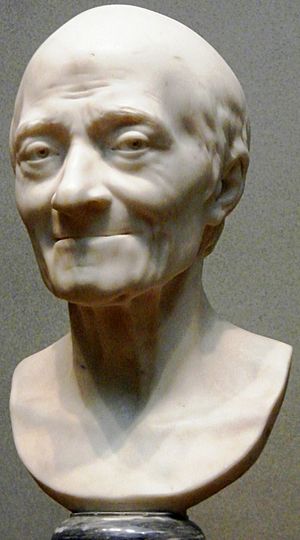

-

Jean-Antoine Houdon, Voltaire, 1778, National Gallery of Art.

-

Voltaire's tomb in the Paris Panthéon.

-

Title page of Voltaire's Candide, 1759.

-

Voltaire at Frederick the Great's Sanssouci, by Pierre Charles Baquoy.

-

An illustration from Candide showing the main character meeting a slave in French Guiana.

-

Voltaire, by Jean-Antoine Houdon, 1778 (National Gallery of Art).

See Also

In Spanish: Voltaire para niños

In Spanish: Voltaire para niños

- Boulevard Voltaire

- List of liberal theorists

- Mononymous persons

- Voltaire Human Rights Awards, Australia

- Voltaire Foundation

- Voltaire Prize for Tolerance, International Understanding and Respect for Differences, University of Potsdam, Germany