Alexander Herzen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Herzen

|

|

|---|---|

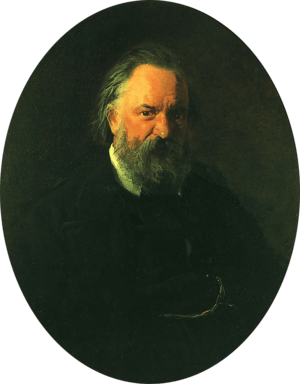

Portrait of Herzen by Nikolai Ge (1867)

|

|

| Born |

Aleksandr Ivanovich Herzen

6 April 1812 Moscow, Moskovsky Uyezd, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire

|

| Died | January 21, 1870 (aged 57) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | Moscow University |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy |

| School | Westernizers Agrarian populism |

|

Main interests

|

Politics, economics, class struggle |

|

Notable ideas

|

Agrarianism |

| Signature | |

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (Russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Ге́рцен, romanized: Alexándr Ivánovich Gértsen; 6 April 1812 – 21 January 1870) was an important Russian writer and thinker. He is often called the "father of Russian socialism" and a key figure in agrarian populism. This means he believed in a society where farmers had more power and land was shared.

Herzen wrote many of his works while living in London. He hoped his writings would help change things in Russia. His ideas helped create a political mood that led to the freedom of serfs (farm workers tied to the land) in 1861. He also wrote a famous novel called Who is to Blame? and his autobiography, My Past and Thoughts, is considered one of the best in Russian literature.

Contents

His Early Life and Exile

Alexander Herzen was born in Moscow in 1812. His father, Ivan Yakovlev, was a wealthy Russian landowner, and his mother was Henriette Wilhelmina Luisa Haag from Germany. His father gave him the name Herzen because he was a "child of his heart" (Herz means heart in German).

He was a cousin to Sergei Lvovich Levitsky, who is known as one of the first important photographers in Russia. Levitsky took a famous picture of Herzen in 1860.

Herzen was born just before Napoleon's army invaded Russia and briefly took over Moscow. His family managed to leave the city safely.

After finishing his studies at Moscow University, Herzen faced trouble. In 1834, he and his friend Nikolay Ogarev were arrested. They were accused of singing songs that were disrespectful to the tsar (the Russian emperor). Herzen was found guilty and sent away to Vyatka (now Kirov) in 1835.

He stayed there until 1837. Then, the tsar's son, Grand Duke Alexander (who later became Tsar Alexander II), visited the city and helped him. Herzen was allowed to move to Vladimir. There, he became the editor of the city's official newspaper. In 1837, he secretly married his cousin, Natalya Zakharina.

Moving to Europe

In 1839, Herzen was set free and returned to Moscow. He met the writer Vissarion Belinsky, who was greatly influenced by Herzen's ideas. Herzen then worked for the government in St. Petersburg and later in Novgorod. In 1846, his father died, leaving him a large amount of money.

In 1847, Herzen left Russia with his family and moved to Italy. He never returned to Russia. When he heard about the revolution in Paris in 1848, he quickly went there. He supported the revolutions happening across Europe but was very disappointed when they failed.

Because he left Russia, his money there was frozen. But a banker named Baron Rothschild helped him get his money back.

Herzen and his wife Natalia had four children. Sadly, his mother and one of his sons died in a shipwreck in 1851. His wife also passed away in 1852 from an illness. That same year, Herzen moved from Geneva to London, where he lived for many years.

In London, Herzen started the Free Russian Press in 1853. He used it to publish books and newspapers that criticized the Russian government. He hoped this would help improve the lives of Russian peasants, whom he greatly admired.

In 1856, his old friend Nikolay Ogarev joined him in London. They worked together on their Russian newspaper called Kolokol (which means "Bell"). Herzen also became friends with other revolutionaries like Bakunin and Marx.

In 1864, Herzen moved back to Geneva and later to Paris. He died in Paris in 1870 from lung problems.

His Political Ideas

Herzen was influenced by thinkers like Voltaire and Hegel. He started as a liberal, meaning he believed in individual rights and freedoms. But he gradually became more interested in socialism, which focuses on community and equality.

He left Russia for good in 1847. However, his newspaper Kolokol, published in London from 1857 to 1867, was read widely in Russia. Herzen combined ideas from the French Revolution with German philosophy. He didn't like the values of the middle class and believed in the simple, honest life of peasants.

He strongly fought for the freedom of Russian serfs. After they were freed in 1861, he pushed for more changes. He wanted people to have more rights, for land to be owned by communities, and for the government to be run by the people.

Herzen was disappointed by the revolutions of 1848 because they didn't bring the changes he hoped for. But he still believed in revolutionary ideas. He always admired the French Revolution and its goals. He believed that society should aim for humanism and harmony. Herzen fought against powerful leaders in Europe and for individual freedom.

He supported both socialism and individualism, believing that people could truly thrive in a socialist society. However, he didn't believe in one big plan for society. Instead, he thought people should live in small communities where their freedom was protected by a government that didn't interfere too much.

His Writings

Herzen began his writing career in 1842. He published an essay called Dilettantism in Science under the pen name Iskander. His next work was Letters on the Study of Nature (1845–46).

In 1847, his novel Who is to Blame? was published. It tells a story about a young tutor whose happy home life is disturbed by another person. The story explores who is responsible for the sad ending.

He also published short stories, which were later collected as Interrupted Tales. In 1850, two more works appeared: From Another Shore and Letters from France and Italy. His autobiography, My Past and Thoughts, was also translated into English as My Exile to Siberia.

Main Works

- Legend (1836)

- Elena (1838)

- Notes of a Young Man (1840)

- Diletantism in Science (1843)

- Who is to Blame? (1846)

- Mimoezdom (1846)

- Dr. Krupov (1847)

- Thieving Magpie (1848)

- The Russian People and Socialism (1848)

- From the Other Shore (1848–1850)

- Letters from France and Italy (1852)

- My Past and Thoughts: The Memoirs of Alexander Herzen

The Free Russian Press

Herzen started his Free Russian Press in London in 1853. He used it to publish many works that spoke out against the Russian government. These included essays like Baptized Property (1853), which attacked serfdom (the system where serfs were tied to the land). He also published magazines such as Polyarnaya Zvyezda (Polar Star) and Kolokol (Bell).

As the first independent Russian political publisher, Herzen's press was very important. The Polar Star and The Bell became very influential. They were secretly brought into Russia, and it was even said that the Emperor himself read them. These publications gave Herzen influence in Russia by reporting from a liberal point of view about the problems with the Tsar and the Russian government.

At first, the Free Russian Press struggled to sell copies or get them into Russia. But after Emperor Nicholas I died in 1855, things changed. Herzen's writings and magazines were smuggled into Russia in large numbers. Their words spread throughout the country and Europe, and their influence grew.

The year 1855 brought hope for Herzen. Alexander II became the new tsar, and reforms seemed possible. Herzen urged the government to move forward with reforms in The Polar Star in 1856. He wrote in 1857 that "A new life is unmistakably boiling up in Russia." The Bell even reported that the government was thinking about freeing the serfs in July 1857.

However, by 1858, the serfs had not yet been fully freed, and Herzen became impatient. The Bell restarted its campaign for their complete freedom. Once the Emancipation reform of 1861 happened, The Bell's campaign changed to "Liberty and Land." This program aimed for more social changes to support the rights of the newly freed serfs. Alexander II did grant serfs their freedom, changed the law courts, and allowed trials by jury.

How People Saw Him

Herzen received criticism from different groups. Some liberals, who were against violence, thought he was too extreme. On the other hand, some radicals thought Herzen was too soft and not revolutionary enough.

Liberals like Boris Chicherin believed that individual freedom would come through logical social changes. They thought that revolutionaries would only delay the ideal society. Herzen, however, believed they were ignoring how history really works.

Russian radicals, such as Nikolay Chernyshevsky, wanted more commitment to violent revolution. They asked Herzen to use The Bell to promote a violent uprising. But Herzen refused. He argued that Russian radicals were not strong or united enough to bring about successful political change. He feared that a new revolutionary government might just replace one harsh rule with another.

Herzen briefly worked with other Russian liberals to encourage a peasant "awakening" in Russia. He continued to use The Bell to promote unity among all parts of Russian society, calling for a national parliament.

However, his hopes of uniting different groups ended with the January Uprising of 1863-1864. During this time, liberals supported the tsar's harsh response against the Poles, while Herzen supported the Polish rebels. This disagreement caused Herzen to lose support, and the readership of The Bell declined. The newspaper stopped publishing in 1867. By the time he died in 1870, Herzen was almost forgotten.

His Influence Later On

Herzen was against the powerful noble class that ruled 19th-century Russia. He supported an agrarian collectivist way of life, where farmers worked together and shared resources. By the 1880s, his writings became popular again as populism grew.

Herzen is also remembered for rejecting corrupt governments and for supporting individual rights. He believed that the complex problems of society couldn't be answered by one single theory. Instead, he thought Russians should live for the present moment, not for a future cause. Herzen believed that big, grand ideas often lead to people being controlled or suffering.

The famous writer Tolstoy said that Herzen had a rare mix of "brilliance and depth." Herzen was also admired by the 20th-century philosopher Isaiah Berlin. Berlin often repeated Herzen's idea that people should not be sacrificed for big, abstract goals or future dreams. Berlin, like Herzen, believed that "the end of life is life itself."

Berlin called Herzen's autobiography "one of the great monuments to Russian literary and psychological genius." He said it should be placed alongside the novels of other great Russian writers like Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Dostoevsky.

A collection of Berlin's essays, Russian Thinkers, which features Herzen, inspired Tom Stoppard's play trilogy The Coast of Utopia. These plays explore the lives and ideas of early Russian socialist thinkers, including Herzen, whose character is central to the story.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Aleksandr Herzen para niños

In Spanish: Aleksandr Herzen para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |