Che Guevara facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Che Guevara

|

|

|---|---|

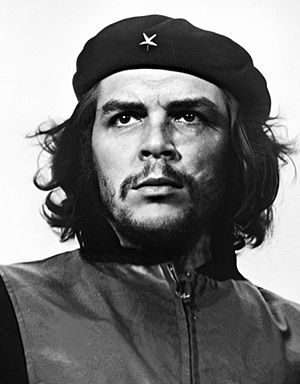

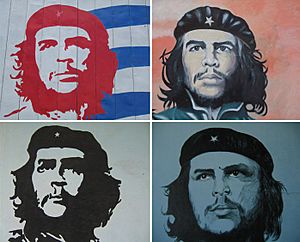

Guerrillero Heroico

Picture taken by Alberto Korda on 5 March 1960, at the La Coubre memorial service |

|

| Minister of Industries of Cuba | |

| In office 11 February 1961 – 1 April 1965 |

|

| Prime Minister | Fidel Castro |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Joel Domenech Benítez |

| President of the National Bank of Cuba | |

| In office 26 November 1959 – 23 February 1961 |

|

| Preceded by | Felipe Pazos |

| Succeeded by | Raúl Cepero Bonilla |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Ernesto Guevara

14 June 1928 Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina |

| Died | 9 October 1967 (aged 39) La Higuera, Santa Cruz, Bolivia |

| Resting place | Che Guevara Mausoleum, Santa Clara, Cuba |

| Citizenship |

|

| Political party | 26th of July Movement (1955–1962) United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (1962–1965) |

| Spouses |

Hilda Gadea

(m. 1955; div. 1959)Aleida March

(m. 1959) |

| Children | 5, including Aleida |

| Alma mater | University of Buenos Aires |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Guevarism |

| Signature |  |

| Nicknames |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Republic of Cuba |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service | 1955–1967 |

| Unit | 26th of July Movement |

| Commands | Commanding officer of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces |

| Battles/wars |

|

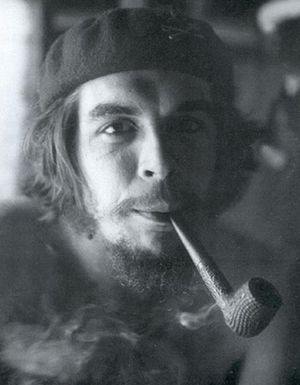

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (born 14 June 1928 – died 9 October 1967) was an Argentine revolutionary. He was a very important leader in the Cuban Revolution. His famous picture has become a symbol of rebellion around the world.

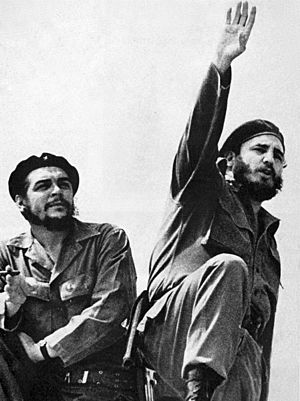

As a young medical student, Guevara traveled across South America. He saw a lot of poverty, hunger, and sickness. This made him want to help change what he saw as unfair treatment of Latin America by the United States. He joined social reforms in Guatemala. When the US helped overthrow Guatemala's president, it made Guevara's political beliefs even stronger. Later, in Mexico City, Guevara met Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl Castro. He joined their group, the 26th of July Movement. They sailed to Cuba on a yacht called Granma. Their goal was to overthrow the Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Guevara quickly became a key leader among the rebels. He played a big part in the two-year fight that removed Batista from power.

After the Cuban Revolution, Guevara took on important roles in the new government. He helped with land reforms as the Minister of Industries. He also helped lead a successful program to teach people across Cuba how to read and write. He was the President of the National Bank and a director for Cuba's armed forces. He also traveled the world as a diplomat for Cuba. These jobs allowed him to help train the soldiers who stopped the Bay of Pigs Invasion. He also played a role in bringing Soviet nuclear missiles to Cuba, which led to the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Guevara was also a writer. He wrote a guide on guerrilla fighting. He also wrote a popular book about his motorcycle trip when he was young. His experiences and studies led him to believe that poor countries were kept poor by powerful nations. He thought the only way to fix this was through worldwide revolution. In 1965, Guevara left Cuba to start revolutions in Africa and South America. He tried in Congo-Kinshasa and later in Bolivia. In Bolivia, he was captured by forces helped by the CIA and was killed.

Guevara is still a debated figure in history. Many books, movies, and songs have been made about him. Some see him as a hero who fought for the poor and wanted a better world. Others criticize him for supporting violence against his opponents. Despite different opinions, Time magazine named him one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century. A photo of him, called Guerrillero Heroico, is known as "the most famous photograph in the world."

Contents

Early Life and Journeys

Ernesto Guevara was born on June 14, 1928, in Rosario, Argentina. He was the oldest of five children. His family was from a good background with Spanish and Irish roots. His father said that Che had "the blood of the Irish rebels" in him, referring to his restless spirit.

From a young age, Ernesto (called Ernestito) cared deeply about poor people. His family had left-leaning ideas, so he learned about many political views. His father supported the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He would host veterans from that war in their home.

Even though he had many severe asthma attacks throughout his life, he was a great athlete. He enjoyed swimming, football, golf, and shooting. He was also a tireless cyclist. He played rugby union and was known for his aggressive style. This earned him the nickname "Fuser," which came from "El Furibundo" (furious) and his mother's last name.

Reading and Learning

Guevara learned chess from his father and played in tournaments by age 12. As he grew up, he loved to read poetry, especially by famous writers like Pablo Neruda and Walt Whitman. He could even recite long poems by heart. His home had over 3,000 books. This allowed him to read widely about many topics. He was interested in writers like Karl Marx, Jules Verne, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

He also liked Latin American writers. He kept notebooks where he wrote down ideas and philosophies from important thinkers. He studied ideas from Buddha and Aristotle. He also looked at Bertrand Russell's ideas on love and patriotism. His favorite school subjects included philosophy, mathematics, history, and sociology. A US intelligence report from 1958 said he was "quite well read" and "fairly intellectual."

Motorcycle Adventures

In 1948, Guevara started studying medicine at the University of Buenos Aires. He wanted to explore the world. He took two long trips that changed how he saw himself and the poverty in Latin America. His first trip in 1950 was a 4,500-kilometer (2,800 mi) solo journey across northern Argentina on a bicycle. He then worked as a nurse on ships for six months.

His second trip in 1951 was a nine-month, 8,000-kilometer (5,000 mi) motorcycle journey through South America. He took a year off from his studies for this trip with his friend, Alberto Granado. Their main goal was to volunteer at a leper colony in Peru, by the Amazon River.

In Chile, Guevara was upset by the tough working conditions of miners. He met a poor communist couple in the desert. He called them "victims of capitalist exploitation." On his way to Machu Picchu, he was shocked by the extreme poverty in rural areas. There, farmers worked small plots of land owned by rich landlords. Later, he was very impressed by the kindness among people living in a leper colony. He said, "The highest forms of human solidarity and loyalty arise among such lonely and desperate people."

Guevara used notes from this trip to write a book called The Motorcycle Diaries. It became a best-seller and was made into a movie in 2004. The journey took him through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and Miami, Florida. By the end of the trip, he saw Latin America as one region that needed to be freed. He believed in a united Hispanic America with a shared heritage. This idea became very important in his later revolutionary work. After returning to Argentina, he finished his studies and became a doctor in June 1953.

Guevara later said that his travels showed him "poverty, hunger and disease." He saw how people couldn't treat a sick child because they had no money. These experiences convinced him that to "help these people," he needed to leave medicine and join the political fight.

Early Political Actions

Guatemala Activism

Ernesto Guevara spent about nine months in Guatemala. In July 1953, he traveled through several Central American countries. He wrote to his aunt that seeing the United Fruit Company's power convinced him that its system was bad for ordinary people. He arrived in Guatemala in December 1953. President Jacobo Árbenz led a government that was trying to make land reforms. They wanted to give uncultivated land from large farms to poor peasants. The United Fruit Company, which owned a lot of land, was most affected by these changes. Guevara liked what was happening in Guatemala. He decided to stay there to become a "true revolutionary."

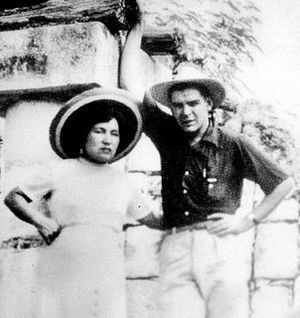

In Guatemala City, Guevara met Hilda Gadea Acosta, a Peruvian economist. She introduced him to important people in the government. Guevara also met Cuban exiles connected to Fidel Castro. During this time, he got his famous nickname, "Che." This was because he often used the Argentine word che, which is like saying "hey" or "pal."

In May 1954, a ship carrying weapons for Guatemala arrived from Czechoslovakia. The United States government, which wanted to remove Árbenz, reacted strongly. They spread anti-Árbenz messages and started bombing raids. The US also supported an armed group led by Carlos Castillo Armas to overthrow the government. On June 27, Árbenz resigned. Armas and his forces took over, and Armas became president. His government arrested and executed suspected communists. They also crushed labor unions and reversed the land reforms.

Guevara wanted to fight for Árbenz. He joined a group organized by young communists. But he was frustrated by their inaction and went back to medical duties. After the coup, he volunteered to fight again. However, Árbenz told his supporters to leave the country. Guevara's calls to resist were noticed, and he was marked for danger. After Hilda Gadea was arrested, Guevara found safety in the Argentine consulate. He stayed there until he could travel to Mexico.

The overthrow of Árbenz made Guevara believe that the US was an imperialist power. He thought the US tried to destroy any government that wanted to fix social inequality. This made him even more convinced that armed struggle was the only way to achieve change. Hilda Gadea later wrote that Guatemala "finally convinced him of the necessity for armed struggle."

Life in Mexico

Guevara arrived in Mexico City on September 21, 1954. He worked as a doctor in hospitals and gave lectures. He also worked as a news photographer. His first wife, Hilda, wrote that he thought about working as a doctor in Africa. He was still very concerned about poverty. Hilda said he was obsessed with an elderly washerwoman he treated. He saw her as "representative of the most forgotten and exploited class." Che wrote a poem for her, promising to fight for a better world for the poor.

During this time, he reconnected with Cuban exiles he had met in Guatemala. In June 1955, he met Raúl Castro, who then introduced him to his older brother, Fidel Castro. Fidel was a revolutionary leader planning to overthrow the dictator Fulgencio Batista. After a long talk with Fidel, Guevara decided that the Cuban cause was what he was looking for. He joined the 26th of July Movement. Even though they had different personalities, Che and Fidel became close friends. They shared a strong commitment to fighting against powerful nations controlling weaker ones.

Guevara believed that US-controlled companies supported harsh governments around the world. He saw Batista as a "US puppet" whose control needed to be broken. He planned to be the group's doctor, but he also trained with the rebels. They learned guerrilla warfare tactics, like quick attacks and retreats. Guevara was the best student in the training. His instructor called him "the best guerrilla of them all."

Guevara married Hilda Gadea in Mexico in September 1955. He then prepared to help free Cuba.

Cuban Revolution

The Granma Invasion

Castro's first step was to attack Cuba from Mexico using an old, leaky boat called the Granma. They set off for Cuba on November 25, 1956. After landing, Batista's army attacked them. Many of the 82 men were killed or captured. Only 22 survived and regrouped. During this first fight, Guevara put down his medical supplies and picked up ammunition. This was a symbolic moment for him.

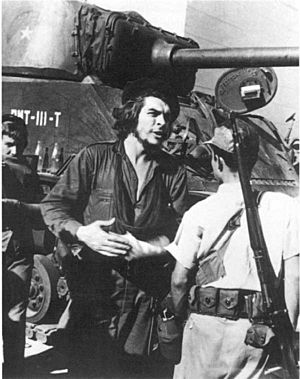

A small group of rebels survived and hid in the Sierra Maestra mountains. They got help from a rebel network and local farmers. The world wondered if Castro was alive. In early 1957, an interview with Herbert Matthews appeared in The New York Times. This article created a powerful image of Castro and the guerrillas. Guevara was not there for the interview. But in the following months, he realized how important the media was to their fight. Supplies and morale were low. Guevara also suffered from painful mosquito bites. He called these "the most painful days of the war."

While living hidden among the poor farmers, Guevara saw that there were no schools or electricity. Healthcare was minimal, and many adults could not read. As the war continued, Guevara became a key part of the rebel army. He impressed Castro with his skills and patience. Guevara set up factories to make grenades and ovens to bake bread. He organized schools to teach farmers to read and write. He also created health clinics and a newspaper. Time magazine later called him "Castro's brain." Castro promoted him to Comandante (commander) of a second army group.

Role as Commander

As second-in-command, Guevara was a very strict leader. He was known for being tough. During the fight, he was also responsible for the quick executions of some men. These men were accused of being informers or traitors. In his diaries, Guevara described the first such execution. It was of a farmer who had betrayed the rebels. Guevara executed him.

Even though he was demanding, Guevara also saw himself as a teacher. He would read to his men during breaks from fighting. He was inspired by the idea of "literacy without borders." He made sure his fighters spent time each day teaching the uneducated farmers to read and write. He called this the "battle against ignorance." One of his soldiers said, "Che was loved, in spite of being stern and demanding. We would (have) given our life for him."

His commanding officer, Fidel Castro, said Guevara was smart, brave, and an excellent leader. Castro also said Guevara took too many risks. A young soldier named Joel Iglesias wrote in his diary about Guevara's bravery in combat. He said that Guevara would run into danger to help wounded soldiers.

Guevara helped create the secret radio station Radio Rebelde (Rebel Radio) in February 1958. It broadcast news to the Cuban people and helped the rebel groups communicate. Guevara was inspired to create the station after seeing how effective radio was in Guatemala.

To stop the rebellion, the Cuban government troops began executing rebel prisoners. They also tortured and shot civilians to scare people. By March 1958, the US stopped selling weapons to Batista's government because of these terrible actions. In late July 1958, Guevara played a key role in the Battle of Las Mercedes. He used his group to stop 1,500 of Batista's soldiers. A US Marine Corps Major later called Che's plan in this battle "brilliant." Guevara also became very good at leading quick attacks against Batista's army. He would then disappear back into the countryside before the army could fight back.

Final Push

As the war continued, Guevara led a new group of fighters towards Havana. They marched for seven difficult weeks, only traveling at night to avoid attacks. They often went days without food. In late December 1958, Guevara's job was to cut the island in half by taking Las Villas province. In just a few days, he won several "brilliant tactical victories." This gave him control of almost the entire province, except for its capital city, Santa Clara. Guevara then led his group in the Battle of Santa Clara. This became the final, most important military victory of the revolution. In the weeks before the battle, his men were sometimes surrounded and outnumbered. Che's victory, despite being outnumbered 10 to 1, is seen by some as an amazing feat in modern warfare.

Radio Rebelde announced on New Year's Eve 1958 that Guevara's group had taken Santa Clara. This was different from the government news, which had even reported Guevara's death. At 3 am on January 1, 1959, Fulgencio Batista learned that his generals were making peace with Guevara. Batista boarded a plane in Havana and fled to the Dominican Republic. He took a lot of money with him. The next day, January 2, Guevara entered Havana to take control of the capital. Fidel Castro arrived six days later, after gathering support in other cities. He entered Havana victoriously on January 8, 1959. About 2,000 people died during the two years of fighting.

Political Career in Cuba

Revolutionary Justice

In mid-January 1959, Guevara went to a summer house in Tarará to recover from a bad asthma attack. There, he started a group to discuss and plan Cuba's future. He also began writing his book Guerrilla Warfare. In February, the government made Guevara a "Cuban citizen by birth" because of his role in the revolution. When Hilda Gadea arrived in Cuba in late January, Guevara told her he was with another woman. They agreed to divorce, which was finalized in May.

The first big political challenge was deciding what to do with Batista's officials who had been cruel. During the rebellion, the rebel army had a law that included the death penalty for serious crimes. In 1959, the new government applied this law to the whole country. They used it for those they called war criminals. The Cuban Ministry of Justice said most people supported this. They compared it to the Nuremberg Trials after World War II.

Castro made Guevara commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison for five months. Guevara was in charge of punishing Batista's army members and those seen as traitors or war criminals. As commander, Guevara reviewed the cases of those judged by revolutionary courts. These courts had army officers and a respected local citizen. Sometimes, the punishment was death by firing squad. Biographers note that in January 1959, many Cubans wanted justice. A survey showed 93% public support for the trials. The new government carried out executions. People would shout "¡al paredón!" (to the wall!).

While accounts differ, it's believed that hundreds of people were executed across the country during this time. Guevara's prison, La Cabaña, had between 55 and 105 executions. Guevara was seen as a "hardened" man. He believed that if executing enemies was the only way to "defend the revolution," he would do it.

Besides justice, Guevara also focused on land reform. On January 27, 1959, he gave an important speech. He said the new government's main goal was "social justice that land redistribution brings about." A few months later, on May 17, 1959, the agrarian reform law written by Guevara became active. It limited the size of all farms. Any land over these limits was taken by the government. It was then given to peasants or kept as state-run farms. The law also said foreigners could not own Cuban sugar plantations.

On June 2, 1959, he married Aleida March, a Cuban member of the 26th of July Movement. They had been living together since late 1958. Guevara had five children from his two marriages.

Early Government Roles

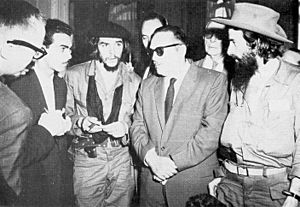

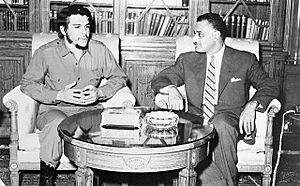

On June 12, 1959, Castro sent Guevara on a three-month trip to many countries. This included Morocco, Egypt, Syria, India, Japan, and Yugoslavia. Sending Guevara away helped Castro seem less connected to Guevara's Marxist ideas. These ideas worried the United States and some of Castro's own group. In Jakarta, Guevara met Indonesian president Sukarno. They talked about Indonesia's recent revolution and planned trade. They quickly became friends, sharing revolutionary goals against powerful Western nations.

Guevara spent 12 days in Japan. He worked on expanding trade with Cuba. He refused to visit a memorial for soldiers lost in World War II. He said Japanese "imperialists" had "killed millions of Asians." Instead, he visited Hiroshima, where the US had dropped an atomic bomb. He called President Truman a "macabre clown" for the bombings. After visiting the museum, he sent a postcard to Cuba saying, "In order to fight better for peace, one must look at Hiroshima."

When Guevara returned to Cuba in September 1959, Castro had more political power. The government had started taking land for reform. But they were slow to pay landowners, offering low-interest "bonds." This worried the United States. Rich cattle owners in Camagüey protested the land changes. They joined with a rebel leader, Huber Matos, who was against communism. They spoke out against "communist encroachment."

At this time, Guevara also became Minister of Finance and President of the National Bank. These roles, along with his job as Minister of Industries, made Guevara very powerful in Cuba's economy. As head of the central bank, he had to sign the Cuban money. Instead of his full name, he signed the bills only "Che." This act shocked many in the financial world. It showed his dislike for money and the class differences it caused. His friend Ricardo Rojo later said that by signing "Che" on the bills, he "literally knocked the props from under the widespread belief that money was sacred."

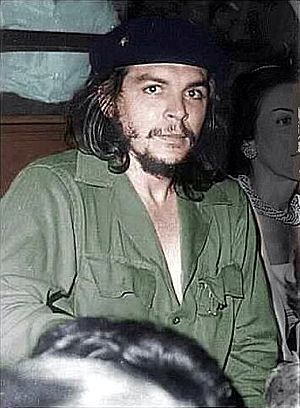

International threats increased on March 4, 1960. Two huge explosions rocked the French ship La Coubre in Havana Harbor. It was carrying Belgian weapons. The blasts killed at least 76 people and injured hundreds. Guevara personally helped some of the victims. Fidel Castro immediately blamed the CIA for "an act of terrorism." The next day, a state funeral was held. At the service, Alberto Korda took the famous photo of Guevara, now known as Guerrillero Heroico.

These threats made Castro decide to remove more "counter-revolutionaries." He used Guevara to speed up land reform. A new government agency, the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), was created. Guevara led it as Minister of Industries. Under his command, INRA formed its own 100,000-person militia. This group first helped the government take control of land and give it out. Later, they set up cooperative farms. The land taken included 480,000 acres owned by US companies.

Months later, the US President Dwight D. Eisenhower greatly reduced US imports of Cuban sugar. Sugar was Cuba's main crop. In response, Guevara spoke to over 100,000 workers on July 10, 1960. He spoke against the "economic aggression" of the United States. Time Magazine reporters who met Guevara then described him as "guid(ing) Cuba with icy calculation, vast competence, high intelligence, and a perceptive sense of humor."

Besides land reform, Guevara emphasized the need for better literacy. Before 1959, Cuba's literacy rate was 60 to 76%. Many people in rural areas could not read or write. So, the Cuban government, at Guevara's urging, called 1961 the "year of education." They sent over 100,000 volunteers into "literacy brigades." These volunteers built schools, trained teachers, and taught peasants to read and write. This campaign was "a remarkable success." By the end, 707,212 adults had learned to read and write. This raised the national literacy rate to 96%.

Guevara also wanted everyone to have access to higher education. The new government introduced affirmative action for universities. Guevara told students at the University of Las Villas that education was no longer just for the "white middle class." He said the university "must paint itself black, mulatto, worker, and peasant." If it didn't, he warned, people would break down its doors.

Economic Changes and the "New Man"

In September 1960, Guevara was asked about Cuba's beliefs. He said, "If I were asked whether our revolution is Communist, I would define it as Marxist." He saw Karl Marx as his guide. Guevara believed that "The laws of Marxism are present in the events of the Cuban Revolution."

To reduce social differences, Guevara and Cuba's leaders quickly changed the country's economy. They took control of factories, banks, and businesses. They tried to make sure all Cubans had affordable housing, healthcare, and jobs. They believed that for real change, people's attitudes and values also had to change. Guevara thought old attitudes about race, women, and manual labor were outdated. He urged everyone to see each other as equals. He called this new way of thinking "el Hombre Nuevo" (the New Man).

Guevara hoped his "new man" would be "selfless and cooperative." This person would be "obedient and hard working," and not care about gender or material things. To achieve this, Guevara focused on Marxism–Leninism. He wanted the state to promote qualities like egalitarianism (equality) and self-sacrifice. "Unity, equality, and freedom" became the new rules.

Guevara's first economic goal for the new man was to remove material rewards. He wanted people to work for moral reasons instead. He saw capitalism as a "contest among wolves" where "one can only win at the cost of others." He wanted to create a "new man and woman." Guevara often said that a socialist economy was not worth the effort if it still encouraged "greed and individual ambition." His main goal was to change "individual consciousness" to create better workers and citizens. He believed Cuba's "new man" would overcome the "egotism" and "selfishness" he saw in capitalist societies.

To promote this "new man," the government created many organizations. These included labor groups, youth leagues, and women's groups. All schools, media, and art centers were controlled by the state. They were used to teach the government's official socialist ideas.

Guevara believed that volunteer work was important for "unity between the individual and the mass." He "led by example." He worked "endlessly at his ministry job, in construction, and even cutting sugar cane" on his days off. He was known for working 36 hours straight. This showed his new program of moral incentives. Workers had to meet a certain quota. Those who did more than their quota received a certificate of praise. Those who did not meet their quota had their pay cut. Guevara defended his ideas about work, saying: "In a capitalist society, people are motivated by money. They work to earn more and more. But in a socialist society, people should be motivated by their desire to help others and build a better world. We want to create a society where work is a joy, not a burden."

When Cuba lost trade with Western countries, Guevara tried to build ties with Eastern Bloc countries. He visited many Marxist nations and signed trade agreements. These agreements helped Cuba's economy but also made it more dependent on the Eastern Bloc.

According to some, Guevara's economic plans were not successful. Productivity dropped, and many workers were absent. He blamed the land reform law from 1959. He thought it still made workers focus on individual ownership instead of the common good. Some critics said Guevara didn't understand basic economic rules.

Bay of Pigs and Missile Crisis

On April 17, 1961, 1,400 US-trained Cuban exiles invaded Cuba. This was known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion. Guevara did not play a direct role in the fighting. The day before, a warship faked an invasion elsewhere, drawing Guevara's forces away. However, historians say he helped Cuba win because he was the director of training for Cuba's armed forces. He had prepared 200,000 men and women for war. During this time, his pistol accidentally went off, grazing his cheek.

In August 1961, at a meeting in Uruguay, Che Guevara sent a note to US President John F. Kennedy. It said, "Thanks for Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs). Before the invasion, the revolution was shaky. Now it's stronger than ever." Guevara also criticized the United States. He said their system was not fair because of "financial control by a few," "discrimination against blacks," and actions by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. He ended by saying the US was not interested in real changes.

Guevara was key in building Cuba's relationship with the Soviet Union. He played a big part in bringing Soviet nuclear missiles to Cuba. This led to the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. This event brought the world very close to nuclear war. Guevara himself traveled to the Soviet Union in August 1962 to sign the final agreement. He wanted the missile deal to be public, but the Soviets insisted on secrecy. By the time Guevara returned to Cuba, the US had already found the missiles.

After the crisis, Guevara was still angry about what he saw as Soviet betrayal. He told a British newspaper that if the missiles had been under Cuban control, they would have fired them. He believed that fighting for socialist freedom against powerful nations was worth the risk of "millions of atomic war victims." The missile crisis made Guevara believe that the US and the Soviet Union used Cuba as a pawn in their global plans. After this, he criticized the Soviets almost as much as he criticized the Americans.

The Great Debate

From 1962 to 1965, Cuba had a "Great Debate" about its economic future. This debate started when Cuba faced an economic crisis. This was due to internal problems, US sanctions, and many skilled people leaving Cuba. Fidel Castro invited Marxist economists from around the world to discuss two main ideas.

Che Guevara believed Cuba could skip a capitalist stage and become a fully "communist" society right away. He thought this could happen if people's awareness and leaders' actions were perfect. The other idea was that Cuba needed a transition period. This would be a mixed economy where Cuba's sugar production was maximized for profit. Only then could a "communist" society be built.

Guevara argued that moral reasons should be the main way to motivate workers. All profits from businesses should go to the state. The state would cover any losses. He believed that building socialist awareness was more important than giving workers material rewards. He thought giving rewards for profit would lead back to capitalism. He also wanted the economy to rely on large group efforts and central planning. The main idea for developing socialism was the "new man." This person would be motivated only by helping others and self-sacrifice.

In 1966, Cuba's economy was reorganized based on moral principles. Cuban messages emphasized volunteering and ideas to increase production. Workers who produced more did not get extra pay. Cuban thinkers were expected to help create a positive national spirit. They were told not to create "art for art's sake." In 1968, all private non-farm businesses were taken over by the state. Economic planning became more flexible. The entire Cuban economy focused on producing a huge sugar harvest. These changes were inspired by the Great Debate. However, focusing so much on sugar made other parts of the Cuban economy underdeveloped.

International Travels

United Nations Speech

In December 1964, Che Guevara became a "revolutionary statesman known worldwide." He traveled to New York City to lead the Cuban delegation and speak at the United Nations. On December 11, 1964, Guevara gave a passionate, hour-long speech. He criticized the UN for not stopping the "brutal policy of apartheid" in South Africa. He asked, "Can the United Nations do nothing to stop this?"

Guevara ended his speech by reciting the Second Declaration of Havana. He called Latin America "a family of 200 million brothers who suffer the same miseries." He said this "epic" would be written by the "hungry Indian masses, peasants without land, exploited workers, and progressive masses." Guevara believed the conflict was a fight of people and ideas. It would be led by those "mistreated and scorned by imperialism." He said that "Yankee monopoly capitalism" now saw its "gravediggers" in these people. Guevara declared that during this "hour of vindication," the "anonymous mass" would write its own history. They would reclaim their "rights that were laughed at by one and all for 500 years." He closed by saying that this "wave of anger" would "sweep the lands of Latin America." He believed that working people, who "turn the wheel of history," were now "awakening from the long, brutalizing sleep."

Guevara later learned that there were two attempts to kill him by Cuban exiles during his UN visit.

While in New York, Guevara appeared on the CBS news show Face the Nation. He met many people, from a US Senator to friends of Malcolm X. Malcolm X admired him, calling Guevara "one of the most revolutionary men in this country right now."

World Tour

On December 17, Guevara left New York for Paris. From there, he started a three-month world tour. He visited China, North Korea, Algeria, Ghana, and Tanzania. He also stopped in Ireland and Prague. In Ireland, Guevara celebrated his Irish heritage on Saint Patrick's Day. He joked to his father that he didn't say much about his family's history in case they were "horse thieves."

During this trip, he wrote a letter that was later called Socialism and Man in Cuba. In it, Guevara called for a new way of thinking, a new way of working, and a new role for individuals.

Guevara ended the essay by saying that "the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love." He urged all revolutionaries to "strive every day so that this love of living humanity will be transformed into acts that serve as examples." He believed the Cuban Revolution was "something spiritual that would go beyond all borders."

Visit to Algeria and Political Shift

In Algiers, Algeria, on February 24, 1965, Guevara made his last public speech on the world stage. He spoke at an economic meeting about African and Asian unity. He said that socialist countries had a moral duty. He accused them of quietly helping Western countries that exploited others. He then listed steps that communist countries should take to defeat powerful nations. He had criticized the Soviet Union, which was Cuba's main financial supporter, in public. He returned to Cuba on March 14 to a quiet welcome from Fidel and Raúl Castro.

His speech in Algiers showed that Guevara now saw the Northern Hemisphere, led by the US and the Soviet Union, as exploiting the Southern Hemisphere. He strongly supported communist North Vietnam in the Vietnam War. He urged people in other developing countries to fight and create "many Vietnams." Che's criticisms of the Soviets made him popular among European thinkers who had lost faith in the Soviet Union. His call to revolution inspired young students in the United States.

In his private writings from this time, Guevara showed growing criticism of the Soviet economy. He believed the Soviets had "forgotten Marx." He criticized their "dangerous" policy of peaceful relations with the US. He also criticized their failure to push for a "change in consciousness" about work. He wanted to get rid of money, interest, and markets. He believed these would only disappear when communism was achieved worldwide. Guevara disagreed with this slow approach. He predicted that if the Soviet Union did not change, it would eventually return to capitalism.

Two weeks after his Algiers speech, Guevara disappeared from public life. His location became a big mystery in Cuba. He was generally seen as second in power only to Castro. His disappearance was linked to problems with his industrialization plans. It was also linked to pressure from Soviet officials who didn't like his pro-Chinese views. There were also serious disagreements between Guevara and Castro about Cuba's economy and ideas. Castro said on June 16, 1965, that people would be told when Guevara wanted them to know. But rumors spread about where he was.

Some retired Cuban officials say that the Castro brothers and Guevara had a strong disagreement after Guevara's Algiers speech. East German embassy files in Cuba show heated arguments between Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. It's unclear if Castro disagreed with Guevara's criticisms of the Soviet Union or just thought it was not helpful to say them publicly.

On October 3, 1965, Castro publicly shared a letter. It was supposedly written by Guevara about seven months earlier. It was later called Che Guevara's "farewell letter." In the letter, Guevara said he still supported the Cuban Revolution. But he announced his plan to leave Cuba to fight for revolution in other countries. He also resigned from all his government and party jobs. He gave up his honorary Cuban citizenship.

Bolivian Mission

Military Involvement in Congo

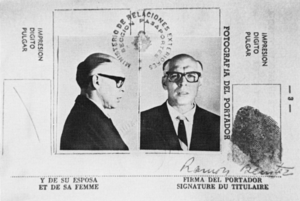

In early 1965, Guevara went to Africa. He wanted to share his knowledge as a guerrilla fighter in the conflict in the Congo. Algerian President Ahmed Ben Bella said Guevara thought Africa was a weak point for powerful nations. He believed it had great potential for revolution. Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser warned Guevara that his plan to fight in Congo was "unwise." He said Guevara would fail. Despite the warning, Guevara traveled to Congo using a fake name.

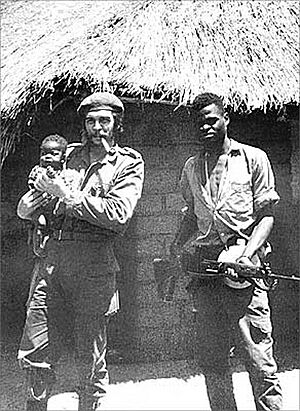

He led the Cuban operation to support the Marxist Simba movement. Guevara, his second-in-command, and 12 other Cubans arrived in Congo on April 24, 1965. About 100 Afro-Cubans joined them soon after. For a while, they worked with a guerrilla leader named Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Guevara admired the late Patrice Lumumba, a former prime minister. He said Lumumba's "murder should be a lesson for all of us." Guevara had limited knowledge of local languages. He was given a teenage interpreter, Freddy Ilanga. Over seven months, Ilanga grew to admire Guevara. He said Guevara "showed the same respect to black people as he did to whites." Guevara soon became disappointed with Kabila's troops. He later said Kabila was not "the man of the hour."

White mercenary troops, supported by anti-Castro Cuban pilots and the CIA, stopped Guevara's movements. They were able to listen to his communications. This allowed them to prevent his attacks and cut off his supplies. Even though Guevara tried to hide his presence, the US government knew where he was. The National Security Agency listened to all his messages.

Guevara wanted to spread the revolution. He taught local fighters about Marxist ideas and guerrilla warfare. In his Congo Diary, he blamed the Congolese rebels' lack of skill and disagreements for the revolt's failure. On November 20, 1965, Guevara left Congo. He was sick with dysentery and asthma. He was also discouraged after seven months of defeats. He left with six Cuban survivors. Guevara had planned to stay and fight until death. But his comrades and two Cuban messengers from Castro urged him to leave. He reluctantly agreed. They quietly packed up their camp, burned their huts, and destroyed weapons. They crossed the border into Tanzania by boat at night.

Months later, Guevara said he left because: "The human element failed. There is no will to fight. The [rebel] leaders are corrupt. In a word... there was nothing to do." He also said, "we cannot liberate, all by ourselves, a country that does not want to fight." A few weeks later, he wrote in his diary, "This is the story of a failure."

Leaving the Congo

Guevara did not want to return to Cuba. Castro had already made his "farewell letter" public. This letter was only supposed to be revealed if he died. In it, he cut all ties to Cuba to focus on worldwide revolution. So, Guevara spent the next six months hiding. He stayed at the Cuban embassy in Dar es Salaam and later in a safehouse near Prague. While in Europe, Guevara secretly visited former Argentine president Juan Perón. Perón was living in exile in Spain. Guevara told Perón about his new plan to start a communist revolution in Latin America, starting with Bolivia. Perón warned him that his plans would fail. But Guevara had already made up his mind. Perón later said Guevara was "an immature utopian... but one of us." He was happy because Guevara was "giving the Yankees a real headache."

During this time abroad, Guevara wrote about his Congo experiences. He also drafted two more books, one on philosophy and one on economics.

Bolivian Mission

Journey to Bolivia

In late 1966, Guevara's location was still a secret. On November 3, 1966, Guevara secretly arrived in La Paz, Bolivia. He used the fake name Adolfo Mena González. He pretended to be a middle-aged Uruguayan businessman.

Three days later, Guevara left La Paz for the rural southeast of Bolivia. He went there to form his guerrilla army. His first base camp was in a dry forest in the remote Ñancahuazú region. Training there was difficult. Not much progress was made in building a guerrilla army. A German agent named Tamara Bunke, known as "Tania," was Che's main contact in La Paz.

Ñancahuazú Guerrilla Group

Guevara's guerrilla force had about 50 men. They called themselves the ELN (National Liberation Army of Bolivia). They were well-equipped. They had some early successes against the Bolivian army in the mountains during early 1967. Because Guevara's groups won several small battles, the Bolivian government thought the guerrilla force was much larger than it was.

Researchers believe Guevara's plan for revolution in Bolivia failed for several reasons:

- Guevara expected help from local people and Bolivia's Communist Party. But he did not receive it. The Communist Party was loyal to Moscow, not Havana. In his diary, Guevara called the Communist Party of Bolivia "distrustful, disloyal and stupid."

- He expected to fight only the poorly trained Bolivian military. But he didn't know that the US government had sent CIA commandos and other agents to help Bolivia. The Bolivian Army also received training and supplies from US Army Special Forces. This included an elite group of US Rangers trained in jungle warfare.

- He expected to stay in radio contact with Cuba. But the two shortwave radios from Cuba were faulty. So, the guerrillas could not communicate or get supplies. This left them isolated.

Guevara was known for preferring fighting over compromise. This had also happened during his time in Cuba and Congo. This made it hard for him to work well with local rebel leaders in Bolivia. In Cuba, Fidel Castro had helped keep this in check.

As a result, Guevara could not get local people to join his group during the eleven months he tried. Many locals even told Bolivian authorities about the guerrillas. Near the end, Guevara wrote in his diary: "Talking to these peasants is like talking to statues. They do not give us any help. Worse still, many of them are turning into informants."

Félix Rodríguez, a Cuban exile working for the CIA, advised Bolivian troops. He helped them hunt for Guevara.

Capture

On October 7, 1967, an informant told the Bolivian Special Forces where Guevara's camp was. On the morning of October 8, 180 soldiers surrounded the area. They moved into the ravine, starting a battle. Guevara was wounded and captured while leading a small group. His biographer, Jon Lee Anderson, reports that a Bolivian Sergeant said Guevara, wounded and with a useless gun, put up his arms and shouted: "Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and I am worth more to you alive than dead."

Guevara was tied up and taken to a small, old schoolhouse in the nearby village of La Higuera that evening. For the next half-day, Guevara refused to answer questions from Bolivian officers. He only spoke quietly to the soldiers. One soldier described Che as looking "dreadful." He had been shot in the right calf. His hair was dirty, his clothes torn, and his feet covered in rough leather. Despite his appearance, he "held his head high, looked everyone straight in the eyes and asked only for something to smoke." The soldier felt sorry for him and gave him tobacco. Guevara smiled and thanked him. Later that night, Guevara, even with his hands tied, kicked a Bolivian officer. The officer had tried to take Guevara's pipe as a souvenir. In another act of defiance, Guevara spat in the face of a Bolivian officer who tried to question him before his execution.

The next morning, October 9, Guevara asked to see the village school teacher, a 22-year-old woman. She later said Guevara was an "agreeable looking man with a soft and ironic glance." She found his "gaze was unbearable, piercing, and so tranquil." During their short talk, Guevara pointed out the poor condition of the schoolhouse. He said it was wrong to expect students to learn there while "government officials drive Mercedes cars." Guevara said, "that's what we are fighting against."

Execution

Later that morning, October 9, Bolivian President René Barrientos ordered Guevara to be killed. The order was given to the soldiers holding Guevara. This was reportedly against the US government's wish to take Guevara to Panama for more questioning. Gary Prado, the Bolivian captain who captured Guevara, said Barrientos ordered the immediate execution. This was to prevent Guevara from escaping and to avoid a public trial that might cause bad publicity.

About 30 minutes before Guevara was killed, Félix Rodríguez tried to ask him about other guerrilla fighters. But Guevara remained silent. Rodríguez and some soldiers helped Guevara stand up. They took him outside to show him to other soldiers. A soldier took a photo of Rodríguez and others with Guevara. Afterward, Rodríguez told Guevara he was going to be executed. A few minutes later, a sergeant entered the hut to shoot him. Guevara reportedly stood up and said his last words: "I know you've come to kill me. Shoot, coward! You are only going to kill a man!" The sergeant then killed him. Guevara was pronounced dead at 1:10 pm local time.

Months earlier, in his last public message, Guevara had written his own words for his tombstone. He said: "Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome, provided that this our battle cry may have reached some receptive ear and another hand may be extended to wield our weapons."

Aftermath

A US government document from October 11, 1967, called the decision to kill Guevara "stupid" but "understandable from a Bolivian standpoint." After the execution, Rodríguez took some of Guevara's personal items, including his watch. He wore it for many years and often showed it to reporters. Today, some of these items, like his flashlight, are on display at the CIA.

On October 15 in Havana, Fidel Castro publicly announced that Guevara was dead. He declared three days of public mourning in Cuba. On October 18, Castro spoke to a crowd of one million people in Havana's Plaza de la Revolución. He spoke about Guevara's character as a revolutionary.

When Guevara was captured, his 30,000-word handwritten diary was also taken. It had entries from November 7, 1966, to October 7, 1967. The diary described the guerrilla campaign in Bolivia. It explained how the guerrillas had to start fighting early because they were discovered. It also showed Guevara's decision to divide his group, which then lost contact. The diary also recorded the disagreement between Guevara and the Communist Party of Bolivia. This meant Guevara had fewer soldiers than he expected. It also showed that Guevara had trouble getting local people to join him. This was partly because the guerrillas learned the wrong local language. As the campaign ended, Guevara became sicker. He had worse asthma attacks. Most of his last fights were to get medicine. The Bolivian diary was quickly translated and shared around the world.

A French writer, Régis Debray, was captured with Guevara in Bolivia in April 1967. He later described the situation. Debray said Guevara's men suffered from hunger, lack of water, and no shoes. He said Guevara and others had an "illness" that made their hands and feet swell. Debray said Guevara was "optimistic about the future of Latin America" despite the difficult situation. He believed Guevara was "resigned to die knowing that his death would be a sort of rebirth."

Che's Legacy

Influence on the Left

Many activists on the radical left admired Guevara's lack of interest in rewards and fame. They agreed that violence was sometimes needed to achieve socialist goals. Even in the United States, students started to copy his style of dress. They wore military uniforms, berets, and grew their hair and beards. This showed they were against US foreign policy. For example, the Black Panthers adopted his black beret. Arab guerrillas named their operations after him.

Trisha Ziff, a documentary director, said that "Che Guevara's significance in modern times is less about the man and his specific history, and more about the ideals of creating a better society." The Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman suggested that Guevara's lasting appeal might be because he rejected material comfort. This is appealing to people who live in a world of consumerism.

To some extent, Guevara's belief in a rebirth after death came true. After pictures of the dead Guevara were shared, his legend grew. Protests against his death happened worldwide. Articles, tributes, and poems were written about him. Rallies supporting Guevara were held from Mexico to Santiago, and from Algiers to Angola. People in Budapest and Prague lit candles for him. His smiling picture appeared in London and Paris. When riots broke out in Berlin, France, and Chicago in 1968, young people wore Che Guevara T-shirts and carried his pictures. A historian said: "In those heady months of 1968, Che Guevara was not dead. He was very much alive."

Finding His Remains

On October 17, 1997, Guevara's remains were buried with military honors. They were placed in a special mausoleum in the Cuban city of Santa Clara. This was where he had won the decisive military victory of the Cuban Revolution.

In July 2008, the Bolivian government showed Guevara's diaries. They were in two old notebooks, along with a logbook and black-and-white photos. Bolivia's vice-minister of culture said they planned to publish photos of every handwritten page. In August 2009, scientists found the bodies of five of Guevara's fellow fighters near a Bolivian town.

Debate About His Life

Guevara's life and legacy are still debated. He was a complex person. He could "use the pen and submachine gun with equal skill." He believed the most important goal was to free people from feeling disconnected from their work. His complex nature is also seen in his different qualities. He was a doctor who cared about people but also used violence. He was a famous international leader who wanted a perfect society but didn't allow disagreement. He was against powerful nations but his image is now sold on many products. Che's story continues to be re-told and re-imagined.

Many famous people have praised Guevara. Nelson Mandela called him "an inspiration for every human being who loves freedom." Jean-Paul Sartre described him as "the most complete human being of our age." Authors like Graham Greene said he represented "gallantry, chivalry, and adventure." Susan Sontag believed his goal was "the cause of humanity itself." In the African community, Frantz Fanon called him "the world symbol of the possibilities of one man." Black Power leader Stokely Carmichael said, "Che Guevara is not dead, his ideas are with us." Even a libertarian writer, Murray Rothbard, called Guevara a "heroic figure." He said Guevara was "the living embodiment of the principle of revolution." Journalist Christopher Hitchens said Che's death "meant a lot to me and countless like me at the time." He was a role model who "fought and died for his beliefs."

On the other hand, some exiled Cuban writers criticize Guevara. Jacobo Machover calls him a "callous executioner." Former Cuban prisoners like Armando Valladares called him "a man full of hatred" who executed people without trial. Carlos Alberto Montaner said Guevara had a "Robespierre mentality." This meant he saw cruelty against enemies as a good thing. Álvaro Vargas Llosa said Guevara's followers "delude themselves by clinging to a myth." He described Guevara as a "Marxist Puritan" who used his power to stop disagreement. He also called him a "cold-blooded killing machine." Llosa also said Guevara's strong beliefs led to the "Sovietization" of the Cuban revolution. He thought Guevara put his ideas above reality.

In a mixed view, British historian Hugh Thomas said Guevara was "brave, sincere and determined." But he was also "obstinate, narrow, and dogmatic." Thomas believed that by the end of his life, Guevara "seems to have become convinced of the virtues of violence for its own sake." After his death, his influence on Castro grew. The Cuban-American sociologist Samuel Farber praised Che Guevara as "an honest and committed revolutionary." But he also criticized him for not fully embracing democracy.

Despite different views, Guevara remains a national hero in Cuba. His picture is on the 3 peso banknote. School children start each morning by saying, "We will be like Che." In his home country of Argentina, high schools are named after him. Many Che museums exist, and a 12-foot bronze statue of him was unveiled in his birth city, Rosario, in 2008. Some Bolivian farmers even see him as "Saint Ernesto" and pray to him for help.

However, Guevara is hated by many in the Cuban exile and Cuban American community in the United States. They see him as "the butcher of La Cabaña." Despite these strong feelings, a famous black-and-white image of Che's face, created by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick, has become a widely sold image. It is found on T-shirts, hats, and other items. This is ironic because Guevara disliked consumer culture. Still, he remains an important figure both in politics and as a popular symbol of youthful rebellion.

International Awards

Guevara received several state honors during his life:

- 1960: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion

- 1961: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross

Archival Media

Video Footage

- Guevara addressing the United Nations General Assembly on 11 December 1964, (6:21), public domain footage uploaded by the UN, video clip

- Guevara interviewed by Face the Nation on 13 December 1964, (29:11), from CBS, video clip

- Guevara interviewed in 1964 on a visit to Dublin, Ireland, (2:53), English translation, from RTÉ Libraries and Archives, video clip

- Guevara interviewed in Paris and speaking French in 1964, (4:47), English subtitles, interviewed by Jean Dumur, video clip

- Guevara reciting a poem, (0:58), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend – Kultur Video 2001, video clip

- Guevara showing support for Fidel Castro, (0:22), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend – Kultur Video 2001, video clip

- Guevara speaking about labor, (0:28), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend – Kultur Video 2001, video clip

- Guevara speaking about the Bay of Pigs, (0:17), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend – Kultur Video 2001, video clip

- Guevara speaking against imperialism, (1:20), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend – Kultur Video 2001, video clip

- Guevara visiting Algeria in 1963 and giving a speech in French, from the Algerian Cinema Archive, video clip

Audio Recording

- Guevara interviewed on ABC's Issues and Answers, (22:27), English translation, narrated by Lisa Howard, 24 March 1964, audio clip

List of English-language Works

- A New Society: Reflections for Today's World, Ocean Press, 1996, ISBN: 1-875284-06-0

- Back on the Road: A Journey Through Latin America, Grove Press, 2002, ISBN: 0-8021-3942-6

- Che Guevara, Cuba, and the Road to Socialism, Pathfinder Press, 1991, ISBN: 0-87348-643-9

- Che Guevara on Global Justice, Ocean Press (AU), 2002, ISBN: 1-876175-45-1

- Che Guevara: Radical Writings on Guerrilla Warfare, Politics and Revolution, Filiquarian Publishing, 2006, ISBN: 1-59986-999-3

- Che Guevara Reader: Writings on Politics & Revolution, Ocean Press, 2003, ISBN: 1-876175-69-9

- Che Guevara Speaks: Selected Speeches and Writings, Pathfinder Press (NY), 1980, ISBN: 0-87348-602-1

- Che Guevara Talks to Young People, Pathfinder, 2000, ISBN: 0-87348-911-X

- Che: The Diaries of Ernesto Che Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2008, ISBN: 1-920888-93-4

- Colonialism is Doomed, Ministry of External Relations: Republic of Cuba, 1964, ASIN B0010AAN1K

- Congo Diary: The Story of Che Guevara's "Lost" Year in Africa Ocean Press, 2011, ISBN: 978-0-9804292-9-9

- Critical Notes on Political Economy: A Revolutionary Humanist Approach to Marxist Economics, Ocean Press, 2008, ISBN: 1-876175-55-9

- Diary of a Combatant: The Diary of the Revolution that Made Che Guevara a Legend, Ocean Press, 2013, ISBN: 978-0-9870779-4-3

- Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War, 1956–58, Pathfinder Press (NY), 1996, ISBN: 0-87348-824-5

- Global Justice: Three Essays on Liberation and Socialism, Seven Stories Press, 2022, ISBN: 1644211564

- Guerrilla Warfare: Authorized Edition, Ocean Press, 2006, ISBN: 1-920888-28-4

- I Embrace You with All My Revolutionary Fervor: Letters 1947-1967, Seven Stories Press, 2021, ISBN: 1644210959

- Latin America: Awakening of a Continent, Ocean Press, 2005, ISBN: 1-876175-73-7

- Latin America Diaries: The Sequel to The Motorcycle Diaries, Ocean Press, 2011, ISBN: 978-0-9804292-7-5

- Marx & Engels: An Introduction, Ocean Press, 2007, ISBN: 1-920888-92-6

- Our America And Theirs: Kennedy And The Alliance For Progress, Ocean Press, 2006, ISBN: 1-876175-81-8

- Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War: Authorized Edition, Ocean Press, 2005, ISBN: 1-920888-33-0

- Self Portrait Che Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2004, ISBN: 1-876175-82-6

- Socialism and Man in Cuba, Pathfinder Press (NY), 1989, ISBN: 0-87348-577-7

- The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, Grove Press, 2001, ISBN: 0-8021-3834-9

- The Argentine, Ocean Press (AU), 2008, ISBN: 1-920888-93-4

- The Awakening of Latin America: Writings, Letters and Speeches on Latin America, 1950–67, Ocean Press, 2012, ISBN: 978-0-9804292-8-2

- The Bolivian Diary of Ernesto Che Guevara, Pathfinder Press, 1994, ISBN: 0-87348-766-4

- The Great Debate on Political Economy, Ocean Press, 2006, ISBN: 1-876175-54-0

- The Motorcycle Diaries: A Journey Around South America, London: Verso, 1996, ISBN: 1-85702-399-4

- The Secret Papers of a Revolutionary: The Diary of Che Guevara, American Reprint Co, 1975, ASIN B0007GW08W

- To Speak the Truth: Why Washington's "Cold War" Against Cuba Doesn't End, Pathfinder, 1993, ISBN: 0-87348-633-1

See Also

In Spanish: Che Guevara para niños

In Spanish: Che Guevara para niños

|

Main:

|

Books:

|

Films:

|

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |