Murray Rothbard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Murray Rothbard

|

|

|---|---|

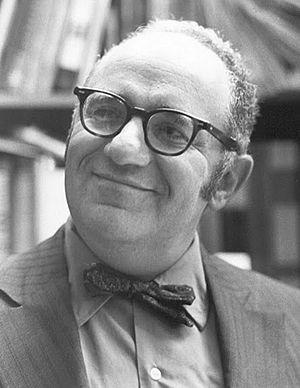

Rothbard in the 1970s

|

|

| Born |

Murray Newton Rothbard

March 2, 1926 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | January 7, 1995 (aged 68) New York City, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Oakwood Cemetery, Unionville, Virginia, U.S. |

| Institution | Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute University of Nevada, Las Vegas |

| Field | Economic history Ethics History of economic thought Legal philosophy Political philosophy Praxeology |

| School or tradition |

Austrian School |

| Alma mater | Columbia University (AB, PhD) |

| Other notable students | Walter Block Hans-Hermann Hoppe |

| Influences | |

| Contributions | Anarcho-capitalism Historical revisionism Paleolibertarianism Left-Libertarianism Title-transfer theory of contract |

Murray Newton Rothbard (born March 2, 1926 – died January 7, 1995) was an American economist, historian, and political thinker. He was a very important person in the American libertarian movement during the 20th century. Rothbard helped create and lead the idea of anarcho-capitalism. He wrote more than twenty books about politics, history, and economics.

Rothbard believed that private businesses could provide services better than the government. He thought the state was like "organized robbery." He also said that fractional-reserve banking (where banks lend out more money than they have) was wrong. He was against central banks and all kinds of government involvement in other countries' affairs. His student Hans-Hermann Hoppe said that without Rothbard, the anarcho-capitalist movement wouldn't exist.

Economist Jeffrey Herbener, who was Rothbard's friend, said that Rothbard was often ignored by mainstream universities. Rothbard didn't agree with common economic methods. Instead, he followed the ideas of Ludwig von Mises, especially something called praxeology. To share his ideas, Rothbard helped start the Mises Institute in Alabama in 1982 with Lew Rockwell and Burton Blumert.

Later in his life, Rothbard supported a mix of libertarian and paleoconservative ideas, which he called Paleolibertarianism. He liked right-wing populism and noted how figures like Joseph McCarthy and David Duke gained support by being against the establishment. In recent years, some critics have seen him as an influence on the alt-right movement.

Contents

Life and Work

Early Life and School

Murray Rothbard's parents, David and Rae Rothbard, came to the United States from Poland and Russia. His father was a chemist. Murray went to a private school in New York City called Birch Wathen Lenox School. He said he liked it much more than public schools.

Rothbard grew up as a "right-winger" while many of his friends were communists. He was part of The New York Young Republican Club when he was young. He said his father believed in small government, free enterprise, and private property. Rothbard felt that socialism was too controlling.

Rothbard studied at Columbia University. He earned a bachelor's degree in mathematics in 1945 and a PhD in economics in 1956. It took him a while to get his PhD because of disagreements with his advisor. He later said that most students at Columbia were very left-wing, and he was one of only two Republicans there.

In the 1940s, Rothbard met Frank Chodorov and read books by libertarian thinkers. In the early 1950s, he attended a seminar by Ludwig von Mises at New York University Stern School of Business. Mises's book Human Action greatly influenced Rothbard. A group called the William Volker Fund paid Rothbard to write a textbook explaining Mises's ideas. This project grew into his book Man, Economy, and State, published in 1962. Mises praised Rothbard's work highly.

Marriage and Career

In 1953, Rothbard married JoAnn Beatrice Schumacher in New York City. She was a historian and helped him with his writing. She also hosted his "Rothbard Salon," where people discussed ideas. They had a loving marriage, and Rothbard called her "the indispensable framework" of his life.

JoAnn said that the Volker Fund allowed Rothbard to work from home for the first 15 years of their marriage. When the fund closed in 1962, Rothbard looked for a job. In 1966, at age 40, he started teaching economics part-time at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. He liked this job because it gave him time to work on libertarian politics.

Rothbard taught there until 1986. Then, at 60, he moved to the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV). He became a distinguished professor of economics there. His friend Hans-Hermann Hoppe said that Rothbard was not well-known in mainstream universities. However, he attracted many students through his writings and became a key figure in the modern libertarian movement. He stayed at UNLV until he died.

Rothbard started the Center for Libertarian Studies in 1976 and the Journal of Libertarian Studies in 1977. In 1982, he co-founded the Ludwig von Mises Institute in Alabama. He was also vice president of academic affairs there until 1995. He also started the institute's Review of Austrian Economics journal in 1987.

After Rothbard died, Joey said he was happy because he never had to wake up before noon for work. He was a "night owl". She remembered how he would start every day with a phone call to his colleague Lew Rockwell, and they would laugh a lot. Rothbard was not religious and called himself an agnostic. He was critical of libertarians who were hostile to religion. The New York Times called Rothbard "an economist and social philosopher who fiercely defended individual freedom against government intervention."

Starting the Mises Institute

The Mises Institute was founded in 1982 by Lew Rockwell, Burton Blumert, and Murray Rothbard. This happened after Rothbard, who helped found the Cato Institute, had disagreements with them. The institute was created to promote the economic ideas of Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Ludwig von Mises, and other Austrian economists.

Disagreements with Ayn Rand

In 1954, Rothbard joined the group around the novelist Ayn Rand, who created Objectivism. He soon left her group, saying her ideas were not as new as she claimed. In 1958, after Rand's novel Atlas Shrugged came out, Rothbard wrote her a fan letter, calling it an amazing book. He said she introduced him to the idea of natural law. Rothbard rejoined Rand's group for a few months but left again because of differences, including his support for anarchism.

Rothbard later made fun of Rand's followers in an unreleased play and an essay. He called Rand's group a "dogmatic, personality cult."

Passing Away

Murray Rothbard died from a heart attack on January 7, 1995, in Manhattan. He was 68 years old.

Ideas and Beliefs

Austrian Economics

Rothbard followed the Austrian School of economics, like his teacher Ludwig von Mises. He believed that economics should not use scientific experiments or statistics. Instead, he used praxeology, Mises's method of using logical reasoning to understand economic laws. He thought economic laws were like math rules: fixed and unchanging.

Hans-Hermann Hoppe, an economist who followed Mises, said that this approach made the Misesian school different from others. He noted that other schools often called it "dogmatic." Mark Skousen, another economist, praised Rothbard's brilliance and writing style. However, Skousen admitted that Rothbard's work was mostly ignored outside his own group.

Rothbard wrote a lot about Austrian business cycle theory. He strongly opposed central banking, fiat money (money not backed by a physical good), and fractional-reserve banking. He supported a gold standard and wanted banks to hold 100% of their deposits as reserves.

Criticizing Mainstream Economics

Rothbard often wrote strong criticisms of other famous economists. He called Adam Smith a "shameless plagiarist" who led economics in the wrong direction, eventually leading to Marxism. Rothbard praised Smith's peers for developing the subjective theory of value. However, David D. Friedman criticized Rothbard's claims about Smith.

Rothbard was also very critical of John Maynard Keynes, calling him weak on economic theory. He believed that Keynesian government control of money caused problems. He also called John Stuart Mill "wooly" and thought Mill's personality affected his economic ideas.

Rothbard criticized Milton Friedman, a monetarist economist. He called Friedman a "statist" and an "apologist" for Richard Nixon. Friedman responded by calling Rothbard a "cult builder and a dogmatist."

Hoppe, Rothbard's student, said that Man, Economy, and State strongly argued against mathematical economics. Hoppe believed Rothbard deserved the Nobel Prize in Economics twice over, even though academia mostly ignored him. Hoppe called Rothbard an "intellectual giant" like Aristotle and John Locke.

Disagreements with Other Austrian Economists

Even though Rothbard called himself an Austrian economist, his methods differed from many others. He criticized Fritz Machlup, another Austrian economist, for not being a true praxeologist.

Rothbard also had different views on the "evenly rotating economy" (ERE), a term Mises used for economic analysis. Most other economists did not adopt Mises's term.

The Economist noted that Rothbard's strong opposition to inflation is gaining influence. However, it contrasted his views with other "sophisticated Austrian-school monetary economists" who follow Hayek in seeking stable spending.

Economist Peter Boettke suggested that Rothbard is better described as a property rights economist. He noted that Rothbard "vehemently attacked all of the books of the younger Austrians."

Ethics and Morality

Rothbard used Mises's logical method for his social and economic ideas. However, he disagreed with Mises on ethics. Mises believed ethical values were subjective, but Rothbard argued for objective, natural law principles. He called this principle "self-ownership," drawing ideas from John Locke and classical liberalism.

Rothbard believed that if someone worked on unowned land, they became its owner forever. After that, it could only change hands through trade or gifts.

Rothbard was a strong critic of egalitarianism (the idea that everyone should be equal). In his book Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature and Other Essays, he wrote that equality is not natural. He thought trying to make everyone equal would have bad results. He believed that the push for equality came from a false idea that reality could be changed by human will.

Noam Chomsky criticized Rothbard's ideal society, saying it would be "full of hate" and "couldn't function for a second."

Anarcho-Capitalism

Rothbard is known for creating the term "anarcho-capitalism" in the mid-20th century. He combined ideas from the Austrian School, classical liberalism, and 19th-century American individualist anarchists. Lew Rockwell said Rothbard was the "conscience" of all libertarian anarchism.

Rothbard wondered if strict libertarian principles meant getting rid of the state entirely. He was influenced by 19th-century individualist anarchists like Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker. He combined Mises's free-market economics with the anarchists' rejection of the state.

Rothbard started calling himself a "private property anarchist" in 1950. Later, he used "anarcho-capitalist" to describe his views. In his anarcho-capitalist model, private companies would provide protection and justice services. These companies would compete in a free market and be supported by customers. Anarcho-capitalists believe this would end the state's monopoly on force.

Rothbard later felt that anarchists were mostly linked to socialism. He suggested a new term, nonarchist, for himself. He argued that anarchism "in practice" often leads to "Communism or chaos."

In Man, Economy, and State, Rothbard divided government interference into three types: "autistic intervention" (interfering with private non-economic activities), "binary intervention" (forced exchange between individuals and the state), and "triangular intervention" (state-ordered exchange between individuals). Rothbard believed that economists might favor more government involvement because it gives them more influence.

Views on Society

Michael O'Malley, a history professor, said Rothbard's views on the civil rights movement and the women's suffrage movement were "contemptuous and hostile." Rothbard criticized women's rights activists, linking them to the growth of the welfare state. He believed the progressive movement was led by certain groups, including "lesbian spinsters."

Rothbard wanted to get rid of the "entire 'civil rights' structure." He said it "tramples on the property rights of every American." He supported repealing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and overturning the Brown v. Board of Education decision. He argued that state-ordered school integration violated libertarian principles. In an essay, he suggested that police should be "unleashed" to deal with "street criminals" and "clear the streets of bums and vagrants."

Rothbard had strong opinions about civil rights leaders. He saw black separatist Malcolm X as a "great black leader." He thought Martin Luther King Jr. was favored by whites because he was a "restraining force" on the Black revolution. He also suggested that opposing Martin Luther King Jr. should be a test for members of his "paleolibertarian" movement.

Opposition to War

Rothbard believed that "war is the health of the state," meaning war makes the government stronger. He thought stopping new wars was important and that understanding how governments led people into past wars was key. He wrote essays like "War, Peace, and the State" and "Anatomy of the State" to explain these ideas.

Rothbard generally condemned war but made two exceptions: the American Revolution and the War for Southern Independence (the American Civil War from the Confederate side). He criticized the "Northern war against slavery," calling it fanatical and destructive. He praised Confederate leaders like Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee as heroes. He criticized Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant for starting "genocide and the extermination of civilians" in their war against the South.

Middle East Conflict

Rothbard's publication, The Libertarian Forum, blamed the Middle East conflict on Israeli actions supported by American money and weapons. He warned that this conflict could draw the United States into a world war. He was anti-Zionist and against U.S. involvement in the Middle East. He criticized the Camp David Accords for not helping Palestinians. He also opposed Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon. In an essay, he said Israel refused to let Palestinian refugees return to their homes.

Historical Revisionism

Rothbard supported "historical revisionism." He believed it could correct what he saw as biased historical stories told by "court intellectuals" who supported the state. Rothbard thought these intellectuals twisted history for their own gain. He said the goal of revisionism was to "present to the public the true history." He was influenced by and praised historian Harry Elmer Barnes. Rothbard agreed with Barnes's view that "the murder of Germans and Japanese was the overriding aim of World War II."

Rothbard's support for World War II revisionism and his connection with Barnes, who denied the Holocaust, drew criticism. Kevin D. Williamson criticized Rothbard for "making common cause with the 'revisionist' historians of the Third Reich," a term for American Holocaust deniers. He said Rothbard and his group were "culpably indulgent" of Holocaust denial.

Ralph Raico, a historian and friend of Rothbard, said that Rothbard was the main reason "revisionism has become a crucial part of the whole libertarian position."

Children's Rights and Parents

In The Ethics of Liberty, Rothbard discussed children's rights based on self-ownership. He was against parents being aggressive towards children. He also opposed the government forcing parents to care for children. He believed children should have the right to run away and find new guardians when they are old enough to choose.

He argued that parents should not have a legal duty to feed, clothe, or educate their children. He thought such duties would force parents to act and take away their rights. However, he believed that in a free society, a "flourishing free market in children" would exist. He thought this market would reduce child neglect.

Economist Gene Callahan noted that Rothbard's legal theory sometimes seemed to ignore the moral issues, such as a parent letting a child starve.

Science and Free Will

In an essay, Rothbard criticized applying causal determinism to humans. He argued that human actions are not fixed by past events but by "free will." He thought that claiming humans are determined was self-contradictory. Rothbard wanted to combine economics, history, ethics, and political science into a "science of liberty." He explained the moral basis for his anarcho-capitalist ideas in For a New Liberty (1973) and The Ethics of Liberty (1982). In Power and Market (1970), he described how an economy without a state might work.

Political Activities

Throughout his life, Rothbard was involved in different political movements to promote his Old Right and libertarian ideas. His first political activity was in 1948, supporting Strom Thurmond's presidential campaign. Rothbard, a Jewish student at Columbia, surprised his peers by organizing a Students for Strom Thurmond group because he strongly believed in states' rights.

By the late 1960s, Rothbard had moved from supporting anti-New Deal politicians to working with anti-war groups. He supported an alliance with the New Left anti-war movement. However, he later criticized the New Left for supporting a military draft. During this time, he worked with Karl Hess and started Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought with Leonard Liggio and George Resch.

From 1969 to 1984, he edited The Libertarian Forum. This publication allowed Rothbard to share his writings and debate with conservatives. Rothbard did not see Ronald Reagan's election in 1980 as a win for libertarian ideas. He criticized Reagan's economic plan, calling claims of spending cuts a "fraud" and a "hoax."

Rothbard criticized both "frenzied nihilism" among left-wing libertarians and those right-wing libertarians who only relied on education to change the state. He believed libertarians should use any moral method to achieve liberty.

Following the idea that "war is the health of the state," Rothbard opposed all wars during his lifetime and actively protested against them. In the 1970s and 1980s, Rothbard was active in the Libertarian Party. He helped found the Cato Institute, naming it after Cato's Letters, which influenced America's Founding Fathers. He opposed the "low-tax liberalism" of 1980 Libertarian Party candidate Ed Clark.

Rothbard left the Radical Caucus of the Libertarian Party in 1983 over cultural issues. He then aligned with the "right-wing populist" part of the party, including Lew Rockwell and Ron Paul. Rothbard worked closely with Lew Rockwell to build the Ludwig von Mises Institute and publish The Rothbard-Rockwell Report.

Paleolibertarianism

In 1989, Rothbard left the Libertarian Party. He started connecting with the anti-interventionist right after the Cold War. He called himself a paleolibertarian, which was a conservative reaction against the cultural ideas of mainstream libertarianism. Paleolibertarianism aimed to attract working-class white people by combining cultural conservatism and libertarian economics.

Reason magazine said Rothbard supported right-wing populism because he was frustrated that mainstream thinkers weren't adopting libertarian views. He suggested that figures like David Duke and Joseph McCarthy could be models for reaching out to a broader group. He believed a libertarian/paleoconservative group could expose the "unholy alliance of 'corporate liberal' Big Business and media elites." He blamed this alliance for creating a "parasitic Underclass" that was "looting and oppressing the bulk of the middle and working classes in America." Rothbard said that David Duke's political program included things like lower taxes, less bureaucracy, and attacking affirmative action, which paleoconservatives and paleolibertarians could support.

Rothbard supported Pat Buchanan's presidential campaign in 1992. When Buchanan dropped out, Rothbard supported Ross Perot. However, Rothbard eventually withdrew his support from Perot and endorsed George H. W. Bush in the 1992 election.

Like Buchanan, Rothbard opposed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). By 1995, he became disappointed with Buchanan, believing his focus on protectionism was turning into support for economic planning and the nation-state.

After Rothbard's death in 1995, Lew Rockwell called him "the founder of right-wing anarchism." William F. Buckley Jr. wrote a critical obituary, criticizing Rothbard's "defective judgment" and views on the Cold War. However, Hoppe, Rockwell, and others at the Mises Institute believed Rothbard was one of history's most important philosophers.

Works

Articles

- The Individualist (Apr., Jul.–Aug. 1971)

- "Soviet Foreign Policy: A Revisionist Perspective." Libertarian Review (Apr. 1978)

- "His Only Crime Was Against the Old Guard: Milken." Los Angeles Times (Mar. 3, 1992)

- "Anti-Buchanania: A Mini-Encyclopedia." Rothbard-Rockwell Report (May 1992)

- "Saint Hillary and the Religious Left." (Dec. 1994)

- "The Other Side of the Coin: Free Banking in Chile." Austrian Economics Newsletter, vol. 10, no. 2.

Books

- Man, Economy, and State. D. Van Nostrand (1962).

- The Panic of 1819: Reactions and Policies. New York: Columbia University Press (1962).

- America's Great Depression. D. Van Nostrand (1973).

- Power and Market: Government and the Economy. Sheed Andrews and McMeel (1970).

- For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto. Collier Books (1973).

- Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature and Other Essays. Libertarian Review Press (1974).

- Conceived in Liberty (4 vol.). New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House (1975–1979).

- The Logic of Action (2 vol.). Edward Elgar Publications (1997).

- The Ethics of Liberty. Humanities Press (1982).

- The Mystery of Banking. Richardson and Snyder, Dutton (1983).

- The Case Against the Fed. Auburn, Alab: Ludwig von Mises Institute (1994).

- An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought (2 vol.). Edward Elgar Publishers (1995).

- Vol. 1: Economic Thought Before Adam Smith.

- Vol. 2: Classical Economics.

- Making Economic Sense. Auburn, Alab: Ludwig von Mises Institute (2007).

- The Betrayal of the American Right. Auburn, Alab: Ludwig von Mises Institute (2007).

Book Contributions

- Introduction to Capital, Interest, and Rent: Essays in the Theory of Distribution, by Frank A. Fetter. Kansas City: Sheed Andrews and McMeel (1977).

- Foreword to The Theory of Money and Credit, by Ludwig von Mises. Liberty Fund (1981).

- "Bramble Minibook" (1973). In: The Essential von Mises. Auburn, Alab: Ludwig von Mises Institute (1988).

Monographs

- Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy. World Market Perspective (1984).

Interviews

- "Interview with Murray Rothbard on Man, Economy, and State, Mises, and the Future of the Austrian School" (Summer 1990). Austrian Economics Newsletter.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Murray Rothbard para niños

In Spanish: Murray Rothbard para niños

- American philosophy

- Alt-right#Influences

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Criticism of the Federal Reserve

- Libertarianism in the United States

- List of American philosophers

- List of peace activists

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |