Noam Chomsky facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Noam Chomsky

|

|

|---|---|

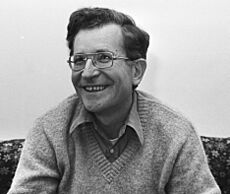

Chomsky in 2020

|

|

| Born |

Avram Noam Chomsky

December 7, 1928 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Education | University of Pennsylvania (BA, MA, PhD) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3, including Aviva |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Transformational Analysis (1955) |

| Doctoral advisor | Zellig Harris |

| Doctoral students |

Gülşat Aygen, Mark Baker, Jonathan Bobaljik, Joan Bresnan, Peter Culicover, Ray C. Dougherty, Janet Dean Fodor, John Goldsmith, C.-T. James Huang, Sabine Iatridou, Ray Jackendoff, Edward Klima, Jan Koster, Jaklin Kornfilt, S.-Y. Kuroda, Howard Lasnik, Robert Lees, Alec Marantz, Diane Massam, James D. McCawley, Jacques Mehler, Andrea Moro, Barbara Partee, David Perlmutter, David Pesetsky, Tanya Reinhart, John R. Ross, Ivan Sag, Edwin S. Williams

|

| Influences |

Academic

J. L. Austin, William Chomsky, C. West Churchman, René Descartes, Galileo, Nelson Goodman, Morris Halle, Zellig Harris, Wilhelm von Humboldt, David Hume, Roman Jakobson, Immanuel Kant, George Armitage Miller, Pāṇini, Hilary Putnam, W. V. O. Quine, Bertrand Russell, Ferdinand de Saussure, Marcel-Paul Schützenberger, Alan Turing, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Political

Mikhail Bakunin, Alex Carey, William Chomsky, John Dewey, Zellig Harris, Wilhelm von Humboldt, David Hume, Thomas Jefferson, Karl Korsch, Peter Kropotkin, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, John Locke, Dwight Macdonald, Paul Mattick, John Stuart Mill, George Orwell, Anton Pannekoek,-Joseph Proudhon]], Rudolf Rocker, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Bertrand Russell, Diego Abad de Santillán, Adam Smith

|

| Influenced |

In academia

John Backus, Derek Bickerton, Julian C. Boyd, Daniel Dennett, Daniel Everett, Jerry Fodor, Gilbert Harman, Marc Hauser, Norbert Hornstein, Niels Kaj Jerne, Donald Knuth, Georges J. F. Köhler, Peter Ludlow, Colin McGinn, César Milstein, Steven Pinker, John Searle, Neil Smith, Crispin Wright

In politics

Michael Albert, Julian Assange, Bono, Jean Bricmont, Hugo Chávez, Zack de la Rocha, Clinton Fernandes, Norman Finkelstein, Robert Fisk, Amy Goodman, Stephen Jay Gould, Glenn Greenwald, Christopher Hitchens, Naomi Klein, Kyle Kulinski, Michael Moore, John Nichols, Ann Nocenti, John Pilger, Harold Pinter, Arundhati Roy, Edward Said, Aaron Swartz

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor, linguist, and political thinker. He is often called "the father of modern linguistics" for his groundbreaking work on how language works. He is also a major figure in analytic philosophy and helped start the field of cognitive science, which is the study of the mind.

Chomsky is a professor at the University of Arizona and previously taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for many years. He has written over 150 books about linguistics, war, and politics. Besides his work on language, Chomsky is famous for his political activism. Since the 1960s, he has been a strong critic of U.S. foreign policy, modern capitalism, and the influence of large companies on the government and media.

Life and Career

Childhood and Education

Noam Chomsky was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Jewish immigrants. His father, William, was a respected scholar who taught his son the importance of free thinking and making the world a better place. From a young age, Noam was interested in politics and anarchism, a belief in a society without rulers.

He read many political books and even wrote his first article at age 10 about a political event in Spain. He went to the University of Pennsylvania at 16. At first, he found college frustrating, but a linguist named Zellig Harris sparked his interest in the study of language. This led him to earn his bachelor's, master's, and eventually his PhD in linguistics in 1955.

Early Career at MIT

In 1955, Chomsky began teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In 1957, he published a very important book called Syntactic Structures. This book changed how people studied language. He challenged the popular idea at the time that language was just a learned behavior. Instead, Chomsky argued that humans are born with a natural ability for language.

He helped create MIT's linguistics program and became a full professor in 1961. His ideas were new and caused a lot of debate, but they made him a leading figure in American linguistics.

Political Activism and Dissent

In the 1960s, Chomsky became a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War. He saw it as an act of American aggression. In 1967, his essay "The Responsibility of Intellectuals" made him famous as a public critic of the government. He joined protests, refused to pay half his taxes, and was arrested several times for his activism.

His political views made him a target, and he was even placed on President Richard Nixon's list of political opponents. Despite this, he continued to write books and speak out against U.S. foreign policy. He also continued his work in linguistics, publishing several more important books.

Media Criticism and Later Career

In the 1970s and 1980s, Chomsky worked with writer Edward S. Herman. Together, they wrote books criticizing U.S. military actions and how the media covered them. Their most famous book, Manufacturing Consent, came out in 1988. It explained their "propaganda model," which argues that the news media often serves the interests of the government and powerful corporations.

Chomsky has always been a strong defender of freedom of speech. In the 1980s, he defended the right of a French writer to express unpopular views, which caused a lot of controversy, especially in France. This showed his belief that everyone should have the right to speak freely, even if their ideas are offensive to others.

Chomsky retired from MIT in 2002 but has continued to research, write, and speak. He opposed the 2003 invasion of Iraq and supported the Occupy movement in 2011, which protested economic inequality. In 2017, he began teaching part-time at the University of Arizona.

Linguistic Theory

Chomsky's ideas about language changed the field of linguistics. He believes that the ability to learn and use language is built into the human brain from birth.

What is Universal Grammar?

Chomsky's most famous idea is called universal grammar. He noticed that children learn to speak their native language very quickly and can create sentences they have never heard before. He said this was possible because all human languages share a basic underlying structure.

According to Chomsky, the human brain is born with a "language acquisition device." This device contains the "rules" of grammar that are common to all languages. When a child learns a language, their brain just needs to figure out the specific vocabulary and variations of that particular language.

What is Generative Grammar?

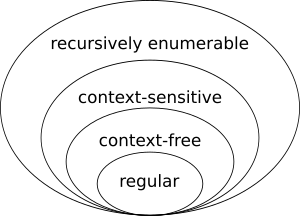

Chomsky also developed generative grammar. This is a theory that tries to explain how we can produce and understand an infinite number of sentences. It suggests that our minds use a set of rules (or a "grammar") to generate sentences.

Think of it like a recipe. With a few basic ingredients (words) and a set of instructions (rules of grammar), you can create an endless variety of dishes (sentences). Chomsky's work aimed to discover what these mental rules are.

Political Views

Chomsky is a well-known political thinker and activist. He describes himself as a libertarian socialist or an anarcho-syndicalist. This means he believes in a society where people have maximum freedom and control over their own lives and workplaces, without powerful governments or corporations in charge.

Criticism of U.S. Foreign Policy

Chomsky is one of the most famous critics of U.S. foreign policy. He argues that the U.S. often acts in its own economic interest, not to spread democracy as it claims. He says the U.S. government supports friendly regimes and tries to stop any movements that challenge its power.

He encourages people to question their government's actions and to apply the same moral standards to their own country as they do to others. He has focused on U.S. actions in places like Vietnam, Latin America, and the Middle East.

Views on Capitalism and the Media

Chomsky is a critic of modern capitalism. He believes that a small, wealthy elite has too much control over the economy and the government. In his view, large corporations and financial institutions make the most important decisions, leaving ordinary citizens with very little say.

He also argues that the mainstream media helps maintain this system. In his book Manufacturing Consent, he explains how the news is "filtered" to promote the views of the government and corporations. He believes that for a society to be truly democratic, people need to think critically and challenge the information they receive from the media.

The Israeli–Palestinian Conflict

Chomsky has written and spoken a lot about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. He supports a peaceful solution where both Israelis and Palestinians can live in safety and dignity. He is a strong critic of Israel's policies toward Palestinians, especially in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. He argues that the U.S. has played a role in preventing a fair settlement to the conflict.

Personal Life

Chomsky is a private person who separates his work from his family life. He was married to linguist Carol Chomsky from 1949 until she died in 2008. They had three children. In 2014, he married Valeria Wasserman.

In June 2023, Chomsky had a major stroke. He was moved to a hospital in São Paulo, Brazil, to recover. He was discharged in June 2024 to continue his recovery at home. While he can no longer speak publicly, he continues to follow world events.

See also

In Spanish: Noam Chomsky para niños

In Spanish: Noam Chomsky para niños

- Anarchism in the United States

- American philosophy

- List of linguists

- List of peace activists

- List of pioneers in computer science

- Theory of language