Rudolf Rocker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rudolf Rocker

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Johann Rudolf Rocker

March 25, 1873 |

| Died | September 19, 1958 (aged 85) Mohegan Colony, New York, United States

|

| Nationality | German |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Political party | Social Democratic Party (SPD) |

| Spouse(s) | Milly Witkop |

| Children | Fermin Rocker |

| Parent(s) | Georg Philipp Rocker Ann Naumann |

Johann Rudolf Rocker (born March 25, 1873 – died September 19, 1958) was a German writer and activist. He believed in anarchism, a political idea that people should be free from government control. He was born in Mainz, Germany, into a Roman Catholic family of craftspeople.

When Rudolf was young, his father died. His mother passed away when he was a teenager, so he lived in an orphanage for a while. As a young person, he worked on river boats and then learned to be a typographer (someone who arranges type for printing). He became involved in trade unionism (workers' groups) and joined a political party. Later, he was influenced by anarchist thinkers like Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. Because of his anarchist activities, he had to leave Germany and went to Paris. In Paris, he learned about syndicalist ideas, which focus on workers' unions changing society.

In 1895, Rudolf moved to London. He lived there for almost 20 years, becoming a key figure in the Yiddish-speaking anarchist community. He edited a newspaper called Arbeter Fraynd and helped organize strikes for workers in the clothing industry. In London, he met and partnered with Milly Witkop, an anarchist from Ukraine. During World War I, he was held as an "enemy alien" because he was German. After the war, he was sent to the Netherlands.

In the 1920s, Rudolf Rocker was mostly in Germany. He helped create the Free Workers' Union of Germany (FAUD), a large workers' union based on syndicalist ideas. He also helped start the International Workers Association (IWA). He became very worried about the rise of nationalism (strong loyalty to one's own country) and fascism (a strict, often violent, political system). He started writing his most important book, Nationalism and Culture, during this time. In 1933, he left Germany for the United States because of the rise of the Nazis. In the U.S., he continued his activism, especially supporting libertarian education and the Spanish Revolution. He published his famous books Nationalism and Culture and Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 1930s.

Contents

Rudolf Rocker's Early Life

Rudolf Rocker was born on March 25, 1873, in Mainz, Germany. His father, Georg Philipp Rocker, was a lithographer (someone who prints using stone). Rudolf was one of four children. His family was Catholic but not very religious. They had a history of supporting democracy and opposing the powerful Prussian government. Rudolf's grandfather even took part in the March Revolution of 1848, which sought more freedom.

Sadly, Rudolf's father died in 1877, when Rudolf was only four years old. His mother's family helped them avoid poverty. In 1884, his mother remarried. Then, in February 1887, his mother died. After his stepfather also remarried, Rudolf was sent to an orphanage.

Rudolf did not like the strict rules and demands for obedience at the Catholic orphanage. He ran away twice. The first time, he just explored the woods around Mainz and came back after three nights. The second time, when he was 14, he ran away because the orphanage wanted him to become a tinsmith. Instead, he worked as a cabin boy on riverboats. He enjoyed traveling to places like Rotterdam. After he returned, he began learning to be a typographer, like his uncle Carl.

Rudolf Rocker's Early Political Ideas

Rudolf's uncle, Carl Rudolf Naumann, had a large library filled with books about socialism. Rudolf was especially interested in the writings of Constantin Frantz, who opposed a strong central German government. He also read novels like Victor Hugo's Les Misérables and traditional socialist books. Rudolf became a socialist and often talked about his ideas with others. He even convinced his employer to become a socialist.

His uncle encouraged him to join the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), a political party. Rudolf became active in the typographers' union in Mainz. He helped with the 1890 election campaign, which was difficult because the government still tried to stop socialist groups. Rudolf helped the SPD candidate win a seat in the German parliament. Important SPD leaders visited Mainz during this time, and Rudolf got to hear them speak.

In 1890, there was a big discussion within the SPD about how to achieve social change. A group called Die Jungen (The Young Ones) wanted a revolution sooner, while party leaders preferred to work through parliament. Rudolf Rocker was part of Die Jungen in Mainz.

In May 1890, he started a reading group called Freiheit (Freedom) to study political ideas more deeply. After Rudolf criticized a party leader and refused to take back his words, he was expelled from the SPD. However, he remained active and gained influence in the socialist workers' movement in Mainz. He had already heard about anarchist ideas, but he fully became an anarchist after attending a socialist meeting in Brussels in August 1891. He was disappointed that the meeting did not strongly oppose war. He was more impressed by Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, a Dutch socialist who later became an anarchist. Rudolf also met Karl Höfer, who smuggled anarchist books into Germany. Höfer gave him important anarchist works by Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin.

Rudolf Rocker believed that political rights come from individuals, not from the government. He wrote that laws alone do not protect freedoms. Instead, freedoms are safe only when people are willing to fight for them.

Rocker became convinced that governments exist because people believe in a higher authority, just as Bakunin said. However, Rocker did not agree that only revolutions could bring change. He was drawn to Bakunin's passionate writing style. Kropotkin's writings, on the other hand, were more logical and described what an anarchist society might look like. Rocker was impressed by Kropotkin's idea that everyone should receive basic necessities from the community.

In October 1891, all members of Die Jungen were either expelled from the SPD or left on their own. They then formed the Union of Independent Socialists. Rudolf became a member and started a local group in Mainz. This group mainly distributed anarchist books smuggled from other countries. He often spoke at union meetings. On December 18, 1892, he spoke at a meeting for unemployed workers. Another speaker, who did not know the local police rules, told the unemployed to take from the rich instead of starving. The police quickly stopped the meeting and arrested that speaker. Rudolf barely escaped. He decided to flee Germany and went to Paris. He had already thought about leaving to learn new languages, meet anarchists abroad, and avoid being forced into the military.

Rudolf Rocker in Paris

In Paris, Rudolf Rocker first met Jewish anarchists. In 1893, he was invited to one of their meetings and was very impressed. Even though he was not Jewish, he often attended their meetings and eventually gave lectures himself. A friend, Solomon Rappaport, let Rudolf live with him because they were both typographers and could share tools. During this time, Rudolf also learned about syndicalist ideas, which combine anarchism with strong workers' unions. These ideas would influence him for a long time. In 1895, because of strong anti-anarchist feelings in France, Rudolf traveled to London. He wanted to see if he could return to Germany, but he was told he would be arrested if he did.

Rudolf Rocker's London Years

First Years in London

Rudolf Rocker decided to stay in London. He found a job as a librarian. There, he met important anarchists like Louise Michel and Errico Malatesta. He was shocked by the poverty he saw in the Jewish East End. He joined the Jewish anarchist group Arbeter Fraint (meaning Workers' Friend). He quickly became a regular speaker at their meetings. There, he met Milly Witkop, a Jewish woman from Ukraine who had come to London in 1894. They became lifelong partners.

In May 1897, Rudolf lost his job. A friend convinced him to move to New York. Milly agreed to go with him. They arrived on May 29, but they were not allowed into the country because they were not legally married. They refused to get married, saying their relationship was a private matter that did not need government approval. This story made headlines in newspapers. They were sent back to England on the same ship.

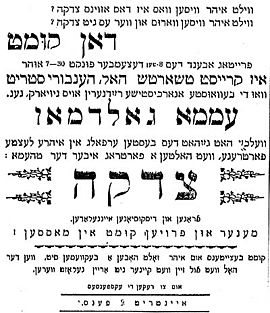

Back in England, Rudolf could not find work. He moved to Liverpool. A friend from London convinced him to edit a new Yiddish newspaper called Dos Fraye Vort (The Free Word), even though he did not speak Yiddish yet. The newspaper only lasted for eight issues. However, it led the Arbeter Fraint group to restart their own newspaper and ask Rudolf to be the editor.

The Arbeter Fraint newspaper struggled financially, even with some money from New York. But many volunteers helped by selling the paper. Rudolf worked hard to fight against the influence of Marxism (another socialist idea) in London's Jewish labor movement. He wrote 25 essays criticizing Marxism for the paper. Because the paper had little money, Rudolf rarely received his small salary and depended on Milly for financial support. Despite his efforts, the paper had to stop publishing. In November 1899, the famous American anarchist Emma Goldman visited London. Rudolf met her for the first time. She gave lectures to raise money for Arbeter Fraint, but it was not enough.

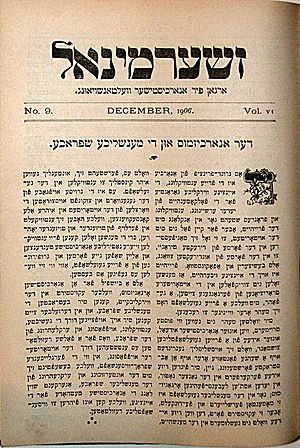

Wanting to continue spreading anarchist ideas, Rudolf founded Germinal in March 1900. This journal was more focused on theory, applying anarchist ideas to literature and philosophy. It showed Rudolf's growing support for Kropotkin's anarchist ideas. Germinal continued until March 1903. In 1902, London's Jewish community faced a wave of anti-immigrant feelings. Rudolf was away in Leeds for a year. When he returned in September, he was happy that the Jewish anarchists had kept the Arbeter Fraint organization going. A meeting of Jewish anarchists in December decided to restart the Arbeter Fraint newspaper as the voice for all Jewish anarchists in Britain and Paris, with Rudolf as editor. The first issue came out on March 20, 1903. After a violent attack on Jews in Russia, Rudolf led a large protest in London to support the victims. He then traveled to other cities to lecture on the topic.

Golden Years of Jewish Anarchism

From 1904, the Jewish labor and anarchist movements in London became very strong. By 1906, Germinal sold 2,500 copies, and Arbeter Fraint sold 5,000 copies. In 1906, the Arbeter Fraint group opened a club for both Jewish and non-Jewish workers. It was called the Workers' Friend Club and was in a former church. Rudolf, now a very good speaker, often gave talks there. Because the club and Germinal were popular, Rudolf became friends with many important non-anarchist Jews in London.

From June 8, 1906, Rudolf was involved in a strike by clothing workers. Wages and working conditions in the East End were very poor. Rudolf was asked to join the strike committee. He spoke regularly at the workers' meetings. The strike failed because the workers ran out of money. By July 1, all workers were back at their jobs.

Rudolf represented the anarchist federation at an international meeting in Amsterdam in 1907. He became a secretary of the new Anarchist International, but it only lasted until 1911. Also in 1907, his son Fermin was born. In 1909, while visiting France, Rudolf spoke out against the execution of an anarchist teacher in Spain. This led to him being sent back to England.

In 1912, Rudolf was again a key figure in a strike by London's clothing makers. In late April, 1,500 tailors from the West End went on strike. By May, 7,000 to 8,000 workers were striking. Since much of the West End work was being done in the East End, the tailors' union there decided to support the strike. Rudolf saw this as a chance for East End tailors to fight against unfair working conditions. He called for a general strike (where all workers stop working). His call was not fully followed, but 13,000 immigrant clothing workers from the East End went on strike after a meeting where Rudolf spoke. Not one worker voted against the strike. Rudolf became a member of the strike committee and was in charge of collecting money and supplies for the striking workers. He also published the Arbeter Fraint newspaper daily to share news about the strike. He spoke at workers' meetings and protests. On May 24, a large meeting was held to discuss a compromise offered by the employers. Rudolf's speech convinced the workers to continue the strike. By the next morning, all of the workers' demands were met.

World War I

Rudolf Rocker was against both sides in World War I. He believed in proletarian internationalism, meaning workers worldwide should unite, not fight each other. While most people expected a short war, Rudolf predicted on August 7, 1914, "a period of mass murder such as the world has never known before." He criticized international socialist groups for not opposing the war. Rudolf and some Arbeter Fraint members opened a soup kitchen to help people who became poorer because of the war. He argued with Kropotkin, who supported the Allies, saying the war was "the contradiction of everything we had fought for."

Soon after this, on December 2, Rudolf was arrested and held as an "enemy alien" because he was German. This was due to strong anti-German feelings in the country. Arbeiter Fraynd was shut down in 1915. The Jewish anarchist movement in Britain never fully recovered from these events.

Rudolf Rocker Returns to Germany

Free Association of German Trade Unions

In March 1918, Rudolf Rocker was sent to the Netherlands as part of a prisoner exchange. He stayed with the socialist leader Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis and recovered from health problems caused by his time in prison. He also reunited with his wife Milly Witkop and son Fermin. In November 1918, he returned to Germany after being invited to help rebuild the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FVdG). This was a radical workers' group that had become more syndicalist and anarchist. During World War I, it had to operate secretly.

Rudolf was against the FVdG working with communists after the November Revolution. He did not agree with Marxism, especially the idea of a "dictatorship of the proletariat" (where the working class controls the government). Soon after arriving in Germany, he became very ill again. He started giving public speeches in March 1919, urging workers to stop making war materials. During this time, the FVdG grew quickly, and its alliance with the communists broke down. All syndicalist members were eventually expelled from the Communist Party. From December 27 to 30, 1919, the FVdG held a national meeting in Berlin.

The organization decided to become the Free Workers' Union of Germany (FAUD) and adopted a new platform written by Rudolf Rocker. This platform rejected political parties and the idea of a communist state. It supported decentralized, economic organizations. It called for public ownership of land and resources but rejected government control. Rudolf criticized nationalism as a "religion of the modern state" and opposed violence. Instead, he supported direct action (workers taking action themselves) and educating workers.

The Height of Syndicalism

After Gustav Landauer's death during an uprising, Rudolf Rocker took over editing Kropotkin's writings in German. In 1920, the government began to suppress revolutionary groups, leading to Rudolf and Fritz Kater being imprisoned. While in prison, Rudolf convinced Kater to fully embrace anarchism.

In the following years, Rudolf became a frequent writer for the FAUD's newspaper, Der Syndikalist. In 1920, the FAUD hosted an international syndicalist meeting, which led to the founding of the International Workers Association (IWA) in December 1922. Rudolf wrote the IWA's platform. In 1921, he wrote a pamphlet called The Bankruptcy of Russian State Communism, criticizing the Soviet Union. He spoke out against what he saw as a huge oppression of freedoms and the suppression of anarchists there. He supported the workers who took part in the Kronstadt uprising and the peasant movement led by the anarchist Nestor Makhno, whom he met in Berlin in 1923. In 1924, Rudolf published a biography of Johann Most, another anarchist.

Decline of Syndicalism

In the mid-1920s, the syndicalist movement in Germany began to decline. The FAUD had about 150,000 members in 1921 but then started losing members to other political parties. Rudolf believed this was because German workers were used to military-like discipline. Around 1925, he started writing Nationalism and Culture, which would become one of his most famous works. In 1925, Rudolf visited North America on a lecture tour, giving 162 speeches. He was encouraged by the anarcho-syndicalist movement he found there.

Returning to Germany in May 1926, he became increasingly worried about the rise of nationalism and fascism. He wrote in 1927: "Every nationalism begins with a Mazzini, but in its shadow there lurks a Mussolini" (Mussolini was a fascist dictator). In 1929, Rudolf helped found a publishing house that released works by other anarchist thinkers. In the same year, he went on a lecture tour in Scandinavia and was impressed by the anarcho-syndicalists there. When he returned, he wondered if Germans could truly embrace anarchist ideas. In the 1930 elections, the Nazi Party gained many votes. Rudolf was worried, saying that if the Nazis came to power, anarchists would suffer.

In 1931, Rudolf attended an IWA meeting in Madrid. In 1933, the Nazis came to power in Germany. After a major fire in the German parliament building on February 27, Rudolf and Milly decided to leave Germany. They heard that another anarchist, Erich Mühsam, had been arrested. After Mühsam's death in July 1934, Rudolf wrote a pamphlet about his suffering. Rudolf reached Switzerland on March 8 by the last train to cross the border without being searched. Two weeks later, Rudolf and his wife joined Emma Goldman in France. There, he wrote about the events in Germany, but it was only published in Spanish.

In May, Rudolf and Milly moved back to London. Many of his Jewish anarchist friends welcomed him. He gave lectures across the city. In July, he attended an IWA meeting in Paris, where they decided to secretly send their newspaper into Nazi Germany.

Rudolf Rocker in the United States

First Years in America

On August 26, 1933, Rudolf and his wife moved to New York. They reunited with their son Fermin, who had stayed there after a lecture tour with his father in 1929. The Rocker family moved to Towanda, Pennsylvania, where many families with progressive ideas lived. In October, Rudolf toured the U.S. and Canada, speaking about racism, fascism, and socialism in English, Yiddish, and German. He found many of his Jewish comrades from London who had moved to America. He became a regular writer for Freie Arbeiter Stimme, a Jewish anarchist newspaper.

Back in Towanda, in the summer of 1934, Rudolf started writing his autobiography. But news of Erich Mühsam's death made him stop. He was working on Nationalism and Culture when the Spanish Civil War began in July 1936. This made Rudolf very hopeful. He published a pamphlet called The Truth about Spain and wrote for The Spanish Revolution, a newspaper about the events in Spain. In 1937, he wrote The Tragedy of Spain, which looked at the events in more detail. In September 1937, Rudolf and Milly moved to the Mohegan Colony, a libertarian community about 50 miles from New York City.

Nationalism and Culture and Anarcho-Syndicalism

In 1937, Nationalism and Culture, which he had started around 1925, was finally published. Anarchists from Chicago helped him. A Spanish version was released in three books in Barcelona, a city known for Spanish anarchists. This would become his most famous work. In the book, Rudolf Rocker suggests that the state (government) and religion are similar. He claims that "all politics is in the last instance religion" because both try to control people and claim to be the source of progress. He argues that culture and power are actually opposing ideas. He looks at human history, including the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and modern society, to support his claims. He ends by calling for a "new humanitarian socialism."

In 1938, Rudolf published a history of anarchist thought called Anarcho-Syndicalism. He traced anarchist ideas back to ancient times. A changed version of this essay was published later as Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in 1949.

World War II and Pioneers of American Freedom

In 1939, Rudolf Rocker had a serious operation and could no longer go on lecture tours. However, in the same year, a committee was formed in Los Angeles to translate and publish his writings. Many of his friends died around this time, and many more were imprisoned by the Nazis. Although Rudolf had disagreed with his teacher Kropotkin for supporting the Allies in World War I, Rudolf argued that the Allied effort in World War II was right. He believed it would help protect freedom. Even though he saw every state as a tool to exploit people, he defended democratic freedoms. This view was criticized by some American anarchists who did not support any war.

After World War II, an appeal in the Freie Arbeiter Stimme newspaper described the difficulties of German anarchists and asked Americans to help them. By February 1946, sending aid packages to anarchists in Germany became a large operation. In 1947, Rudolf published Regarding the Portrayal of the Situation in Germany. In this work, he wrote about how difficult it would be for another anarchist movement to grow in Germany. He thought young Germans were either cynical or leaning towards fascism. He believed a new generation would need to grow up before anarchism could flourish again. Nevertheless, a group called the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (FFS) was founded in 1947 by former FAUD members. Rudolf wrote for their newspaper, Die Freie Gesellschaft, which lasted until 1953. In 1949, Rudolf published another well-known book, Pioneers of American Freedom. In this collection of essays, he explored the history of liberal and anarchist ideas in the United States. He wanted to show that radical thought was not foreign to American history but had always been a part of its culture.

Rudolf Rocker's Final Years

On his 80th birthday in 1953, a dinner was held in London to honor Rudolf Rocker. Famous people like Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Herbert Read, and Bertrand Russell sent messages of tribute. Rudolf Rocker passed away on September 19, 1958, at the age of 85.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rudolf Rocker para niños

In Spanish: Rudolf Rocker para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |