Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Austrian Revolutions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the revolutions of 1848 | |||

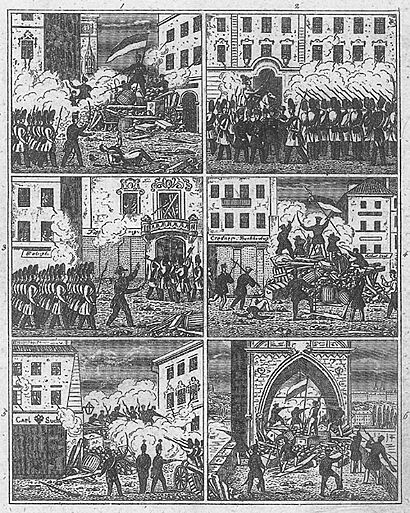

Barricades in Prague during the revolutionary events

|

|||

| Date | 13 March 1848 – November 1849 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Goals |

|

||

| Resulted in | Counterrevolutionary victory

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

The Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire were a series of big changes and uprisings that happened between March 1848 and November 1849. The Austrian Empire was a large country ruled from Vienna. It was home to many different groups of people, like Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Slovenes, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Italians, and Serbs. Each group had its own culture and language. During these revolutions, many of these groups wanted more control over their own lands, or even to become completely independent. This desire for self-rule is called nationalism.

Things got even more complicated because at the same time, people in the nearby German states were also trying to unite into one big German nation. Besides these nationalist feelings, many people also wanted more freedom and fairness. These ideas, called liberalism (wanting more individual freedoms) and socialism (wanting more equality for everyone), challenged the old, traditional ways of the Empire.

Contents

Why Did People Rebel in 1848?

The events of 1848 were the result of many problems building up after a big meeting called the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Before 1848, the Austrian Empire was very traditional and didn't like new ideas. It limited what people could say in newspapers and what students could do at universities.

Social and Political Problems

There were many disagreements between farmers who owed money and those they owed money to. There were also fights over land rights, especially in Hungary. People also argued a lot about religion. The Empire was often involved in wars to keep things the same across Europe. These wars cost a lot of money and needed many soldiers. Sometimes, ordinary people were forced to join the army, which led to fights between soldiers and civilians. Farmers were also unhappy because they still had to work for nobles without pay, a system called feudalism.

Even though there wasn't much freedom to publish or gather, many educated people, especially students, wanted changes. They talked about better education and more basic freedoms. They believed that forcing people to work was not efficient and that workers should be paid. The big question was how to make these changes happen.

People in Vienna met in clubs and coffeehouses to discuss these ideas. They wanted less censorship, religious freedom, and more economic opportunities. They also wanted a better government. However, they didn't yet ask for things like a constitution or the right for everyone to vote.

There were also many educated young people who couldn't find jobs. This made them feel frustrated and want even bigger changes.

The Impact of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, which brought new factories and machines, reached Austria in the 1840s. This was a major reason for the revolutions. While it brought new ways of making things, it also hurt small businesses and created tough working conditions for many people. This made ordinary citizens, especially those in the middle and lower classes, more open to revolutionary ideas and wanting things to change.

Revolution Spreads Across Austrian Lands

Early Victories and New Challenges

When news arrived that revolutionaries had won in Paris in February 1848, uprisings quickly spread across Europe, including in Vienna. People in Vienna demanded that Prince Metternich, a very conservative and powerful minister, resign. Since no one came to Metternich's defense, he stepped down on March 13. He then left for London. Emperor Ferdinand I appointed new ministers who seemed to support more freedom.

The old system fell apart quickly because the Austrian army was not strong enough everywhere. General Joseph Radetzky could not stop rebels in Venice and Milan (parts of Italy controlled by Austria). He had to pull his troops out of those areas.

For a short time, people across the continent celebrated these victories for freedom. Many new groups formed, and more people started taking part in government decisions.

However, the new ministers struggled to keep control. Provisional governments in Venice and Milan wanted to join an Italian group of states. A new Hungarian government in Pest also wanted to break away from the Empire and have Ferdinand as their own king. A Polish group in Galicia had similar goals.

Growing Tensions After the "Springtime of Peoples"

After the initial victories, many people from the lower classes felt it was their chance to demand more. There were protests against taxes and attacks on tax collectors in Vienna. Soldiers retreating from Milan were also attacked. The leader of the church in Vienna had to flee, and a religious building in Graz was destroyed.

The idea of nationalism also caused problems. Different national groups started to claim power and unity for themselves. In Italy, Charles Albert of Sardinia, the King of Piedmont-Savoy, started a war against Austria in the northern Italian provinces. This war took up everyone's attention in Italy.

In Germany, people debated whether Austria should be part of a united German state. This question divided the Frankfurt Parliament. The ministers in Vienna allowed elections for the German National Assembly in some Habsburg lands. However, it was unclear which areas would participate. Hungary and Galicia were clearly not German. German nationalists believed that the Czech lands (like Bohemia and Moravia) should be part of a united Germany, even though most people there spoke Czech, a Slavic language. Czech nationalists disagreed, seeing their language as very important. They called for people in Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia to boycott the Frankfurt Parliament elections. Tensions between German and Czech nationalists quickly grew in Prague.

After the end of forced labor (serfdom) on April 17, a group called the Supreme Ruthenian Council formed in Galicia. They wanted to unite all ethnic Ukrainian lands into one province. A Ukrainian language department opened at Lviv University, and the first Ukrainian newspaper, Zoria Halytska, started publishing in Lviv on May 15, 1848. Forced labor also ended in Bukovina on July 1.

By early summer, the old governments were gone, and new freedoms like freedom of the press and assembly were in place. Many national groups made their demands. New parliaments held elections to create new constitutions. However, the election results were often surprising. Many new voters, who were not used to political power, often elected traditional or only slightly liberal leaders. The radicals, who wanted the most change, often lost.

These new assemblies had a difficult job: they had to meet the needs of the people and decide what the country itself should look like. The Austrian Assembly was split into Czech, German, and Polish groups, each with different political views. Outside the Assembly, people used petitions, newspapers, protests, and clubs to pressure their new governments.

The Czechs held a Pan-Slavic congress in Prague from June 2 to June 12, 1848. Most participants were "Austroslavs" who wanted more freedom within the Empire. However, many of them were farmers or workers, surrounded by a German middle class, which made it hard for them to achieve their goals. They also did not want Bohemia to be taken over by a German Empire.

The Counterrevolution Begins

Rebels in Vienna quickly lost street fights to Emperor Ferdinand's troops, led by General Radetzky. This caused several liberal government ministers to resign. Ferdinand, now back in power in Vienna, appointed conservative ministers instead. This was a big setback for the revolutionaries. By August, most of northern Italy was back under Radetzky's control.

In Bohemia, the leaders of both the German and Czech nationalist movements supported a king and were loyal to the Habsburg Emperor. Just days after the Emperor regained control of northern Italy, Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz took actions in Prague that led to street fighting. Once barricades went up, he used Habsburg troops to crush the rebels. After taking back the city, he declared strict military rule, disbanded the Prague National Committee, and sent delegates from the "Pan-Slavic" Congress home. German nationalists were happy about this, not realizing that the Habsburg military would soon crush their own national movement too.

Attention then turned to Hungary. The war there again threatened the Emperor's rule, causing Emperor Ferdinand and his court to flee Vienna once more. Radicals in Vienna welcomed Hungarian troops, seeing them as the only force that could stand against the Emperor. However, the radicals only controlled the city for a short time. Windisch-Grätz brought soldiers from Prussia to quickly defeat the rebels. Taking back Vienna was seen as a defeat for German nationalism.

At this point, Ferdinand I named Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg as the head of government. Schwarzenberg convinced the weak-minded Ferdinand to give up his throne to his 18-year-old nephew, Franz Joseph. Parliament members continued to debate, but they no longer had real power over state decisions.

Both the Czech and Italian revolutions were defeated by the Habsburgs. Prague was the first major victory for the forces against the revolution in the Austrian Empire.

Lombardy-Venetia was quickly brought back under Austrian control. Support for the revolution had faded because revolutionary ideas were mostly popular among the middle and upper classes. They failed to win over the lower classes or convince people about Italian nationalism. Most ordinary people were quite indifferent, and many Lombard and Venetian troops remained loyal to Austria. The only strong support for the revolution was in the cities of Milan and Venice. The Republic of San Marco in Venice held out under siege until August 28, 1849.

Revolution in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Hungarian parliament, called the Diet, met again in 1825 to deal with money problems. A group wanting more freedom, called the liberal party, grew in the Diet. They tried to help farmers, but often in ways that didn't fully understand their needs. Lajos Kossuth became a leader for the lower nobles in the Diet.

In 1848, when news of the revolution in Paris arrived, a new Hungarian government took power with Kossuth as a key figure. The Diet approved a major set of changes called the "April laws" (or "March laws"). These laws changed almost everything about Hungary's economy, society, and politics. Here are some of the main points:

- Freedom of the Press: No more government censorship.

- Accountable Ministries: Government ministers had to be elected by the parliament, not just chosen by the king.

- Annual Parliament: The parliament would meet regularly in Pest.

- Equality Before the Law: Everyone, rich or poor, had the same laws. All religions were free.

- National Guard: Hungary would have its own police force to keep order.

- Fair Taxes: Everyone, including nobles, had to pay taxes.

- End of Forced Labor: The old system of feudalism and serfdom (where farmers worked for nobles without pay) was abolished.

- Juries and Representation: Ordinary people could serve on juries and hold public office if they were educated.

- National Bank: Hungary would have its own bank.

- Loyal Army: The army had to support the constitution. Hungarian soldiers would not be sent abroad, and foreign soldiers had to leave Hungary.

- Free Political Prisoners: People jailed for their political beliefs were released.

- Union with Transylvania: Hungary and Transylvania would unite.

In April 1848, Hungary became one of the first countries in Europe to have democratic parliamentary elections. The new voting law gave more people the right to vote than almost anywhere else in Europe at the time. The April laws completely removed all special privileges for Hungarian nobles.

The Emperor's court found these demands difficult to accept, but their weak position left them with little choice. One of the first things the Diet did was to end serfdom, which was announced on March 18, 1848.

The Hungarian government tried to limit the political activities of the Croatian and Romanian national movements. These groups also wanted self-rule and didn't see why they should simply trade one central government (Austria) for another (Hungary). This led to armed clashes between Hungarians and Croats, Romanians, Serbs, and Slovaks.

The Habsburg Kingdom of Croatia and the Kingdom of Slavonia broke ties with the new Hungarian government in Pest. They chose to support the Emperor instead. Josip Jelačić, a conservative who was appointed as the new leader (called a ban) of Croatia-Slavonia by the Emperor, was removed from his position by the Hungarian government. But he refused to give up his power. So, there were two governments in Hungary giving different orders in the Emperor's name.

Knowing that a civil war was likely in mid-1848, the Hungarian government tried to get the Emperor's support against Jelačić. They offered to send troops to northern Italy to help Austria. They also tried to negotiate with Jelačić, but he insisted that the Emperor's power be fully restored as a condition for any talks. By the end of August, the imperial government in Vienna officially ordered the Hungarian government to stop plans for its own army. Jelačić then took military action against the Hungarian government without waiting for an official order.

The May Assembly of Serbs in the Austrian Empire took place from May 1 to 3, 1848. During this meeting, the Serbs declared their own self-governing region called Serbian Vojvodina. A war began, leading to battles like the siege of Srbobran on July 14, 1848, where Hungarian forces were forced to retreat by strong Serbian defenses.

With war happening on three fronts (against Romanians and Serbs in Banat and Bačka, and Romanians in Transylvania), Hungarian radicals in Pest saw an opportunity. The parliament made some agreements with the radicals in September to avoid more violence. Soon after, the final break between Vienna and Pest happened. General Count Franz Philipp von Lamberg was given control of all armies in Hungary, including Jelačić's. When Lamberg was attacked upon arriving in Hungary a few days later, the Emperor's court ordered the Hungarian parliament and government to be dissolved. Jelačić was appointed to take Lamberg's place. The war between Austria and Hungary had officially begun.

This war led to the Vienna Rebellion (also called the October Crisis) in Vienna. Rebels attacked a group of soldiers who were on their way to Hungary to help Jelačić's forces.

After Vienna was retaken by the Emperor's forces, General Windischgrätz and 70,000 troops were sent to Hungary to crush the revolution. As they advanced, the Hungarian government left Pest. However, the Austrian army had to retreat after big defeats in the Hungarian Army's Spring Campaign from March to May 1849. Instead of chasing the Austrian army, the Hungarians stopped to retake the Fort of Buda and prepare their defenses. In June 1849, Russian and Austrian troops entered Hungary, greatly outnumbering the Hungarian army. Kossuth resigned on August 11, 1849, giving power to Artúr Görgey, who he believed was the only general who could save the nation.

In May 1849, Czar Nicholas I of Russia promised to increase his efforts against the Hungarian Government. He and Emperor Franz Joseph began to gather and rearm an army. The Czar also prepared to send 30,000 Russian soldiers from Poland.

On August 13, after many difficult defeats in a hopeless situation, Görgey signed a surrender at Világos (now Șiria, Romania) to the Russians. The Russians then handed the Hungarian army over to the Austrians.

Slovak Uprising

The Slovak Uprising was a revolt by Slovaks against control by ethnic Hungarians in what is now Western Slovakia. It was part of the larger 1848/49 revolution in the Habsburg Monarchy and lasted from September 1848 to November 1849. During this time, Slovak patriots created the Slovak National Council to represent them politically. They also formed military groups called the Slovak Volunteer Corps.

The Slovak movement's goals for political, social, and national rights were written down in a document called "Demands of the Slovak Nation" in April 1848.

Serb Revolution of 1848–1849

The Serb Revolution of 1848 was an uprising of Serbs living in Vojvodina against control by ethnic Hungarians. Most Serbs in this area sided with the Austrians. However, there were a few exceptions, like General János Damjanich of the Hungarian Revolutionary Army.

The Second Wave of Revolutions

In 1849, revolutionary groups faced a new challenge: they needed to work together to defeat their common enemy. Before this, the Habsburg forces had often won by using the different national groups against each other. New democratic efforts in Italy in the spring of 1848 led to more fighting with Austrian forces in Lombardy and Venetia.

On the first anniversary of the first barricades in Vienna, German and Czech democrats in Bohemia agreed to put aside their disagreements and plan together for the revolution. Hungarians faced the biggest challenge in overcoming the divisions from the previous year, as the fighting there had been very intense. Despite this, the Hungarian government hired a new commander and tried to unite with the Romanian democrat Avram Iancu, known as Crăișorul Munților ("The Prince of the Mountains"). However, the divisions and mistrust were too strong.

Three days after fighting started again in Italy, Charles Albert of Sardinia gave up his throne in Piedmont-Savoy. This effectively ended Piedmont's return to the war. These new military conflicts cost the Empire the little money it had left.

Another challenge to the Habsburgs came from Germany. People debated whether to have a "big Germany" (a united Germany led by Austria) or a "little Germany" (a united Germany led by Prussia). The Frankfurt National Assembly suggested a constitution with Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia as the king of a united Germany made up only of "German" lands. This would have meant Austria and Hungary (as a "non-German" area) would only be linked by having the same ruler, not as a united state. This was not acceptable to either the Habsburgs or the German liberals in Austria. In the end, Friedrich Wilhelm refused to accept the constitution.

Schwarzenberg dissolved the Hungarian Parliament in 1849 and put his own constitution in place, which gave no power to the liberal movement. He appointed Alexander Bach to lead internal affairs. Bach created a system that stopped political disagreement and controlled liberals within Austria, quickly bringing things back to how they were before. After the Hungarian nationalist leader Lajos Kossuth was sent away, Schwarzenberg faced more uprisings from Hungarians. Using Russia's traditional conservative views, he convinced Tsar Nicholas I to send Russian forces. The Russian army quickly crushed the rebellion, forcing the Hungarians back under Austrian control. In less than three years, Schwarzenberg had brought stability and control back to Austria. However, Schwarzenberg had a stroke in 1852, and his successors could not maintain the strong control he had established.

See also

- United Slovenia

- Anton Füster

- Revolutionary Spring: Fighting for a New World 1848–1849 by Christopher Clark