Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1772–1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

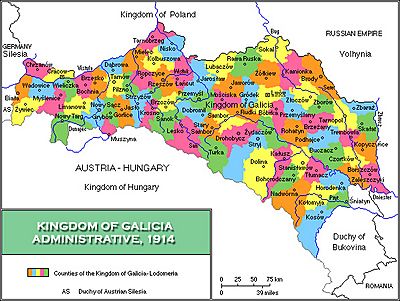

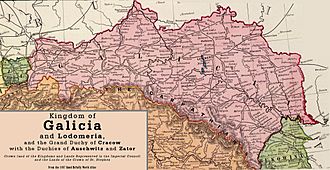

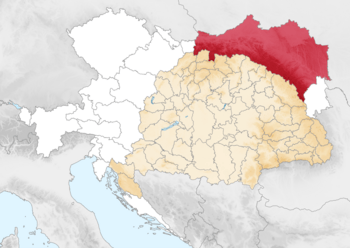

Galicia and Lodomeria in Austria-Hungary (map showing territorial scope from 1849 to 1918)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Crown land of the Habsburg monarchy (1772–1804) Crownland of the Austrian Empire (1804–1867) Crownland of the Cisleithanian part of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Lemberg | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Official language: German Language of government (since 1867): Polish Minority language: Ruthenian Ukrainian Yiddish By census 1910: Polish 58.6% Ruthenian 40.2% |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

Minority

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy (1772–1860) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1772–1780 (first)

|

Maria Theresa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1916–1918 (last)

|

Charles I | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1772–1774 (first)

|

J. A. von Pergen | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1917–1918 (last)

|

Karl Georg Huyn | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Diet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• First Partition of Poland

|

August 5 1772 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Claimed by West UPR

|

October 19, 1918 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| November 14, 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| September 10, 1919 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Total

|

78,497 km2 (30,308 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1910

|

8,025,675 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

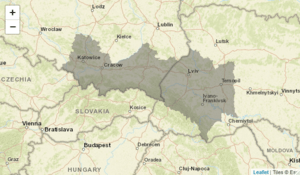

| Today part of | Poland Ukraine Romania |

||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, also known as Austrian Galicia, was a special region within the Austrian Empire. It was created in 1772 and was like a "crown land," meaning it was directly controlled by the ruler. This kingdom was formed from parts of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that Austria took over.

Later, in 1804, it became a crown land of the new Austrian Empire. From 1867, it was part of the Austrian side of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was a dual monarchy (two separate kingdoms under one ruler). Galicia and Lodomeria had some freedom to govern itself. This setup lasted until 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire broke apart.

The name "Galicia" comes from "Halych", an old kingdom in the medieval Kievan Rus'. "Lodomeria" comes from "Volodymyr", a city founded in the 10th century. The title "King of Galicia and Lodomeria" was first used by Andrew II of Hungary in the 13th century. This old title was later used by the Habsburg rulers to claim the region. After World War II, the area of Galicia was split between modern-day Poland and Ukraine.

Contents

History of Galicia

In 1772, the Habsburg monarchy took over a large part of Poland, and this area became Galicia. The capital of Austrian Galicia was Lviv (called Lemberg in German). Even though many people in the eastern part of Galicia were Ukrainians, the region was mostly controlled by Polish nobles. There were also many Jewish people, especially in the eastern areas.

In the early years of Austrian rule, Galicia was managed very strictly from Vienna, the capital of Austria. Many important changes were made by German and Czech officials. The nobles kept their rights, but these rights were limited. People who were once like servants (serfs) gained more freedom. They could marry without their lord's permission and could complain to the emperor's courts if they were treated unfairly. The Greek Catholic Church, which served the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) people, was given more importance and support. These changes made many ordinary people, both Polish and Ukrainian, feel good about the emperor. However, Austria also took a lot of wealth from Galicia and made many peasants join the army.

Changes from 1815 to 1860

In 1815, after the Congress of Vienna, some parts of Galicia were given to Congress Poland, which was ruled by Russia. The Ternopil region was returned to Austria by Russia. The city of Kraków became a special, semi-independent city.

The 1820s and 1830s were a time when Austria ruled Galicia very closely. Most government jobs went to German-speaking people. After a Polish uprising in Russian Poland in 1830–31, many Polish refugees came to Galicia. In 1846, there was an unsuccessful Polish uprising in Galicia. Austrian forces easily stopped it with the help of local peasants. These peasants, who were suffering from poor harvests, saw no benefit in an independent Poland and instead rose up against their landlords, killing many of them. After this, Kraków lost its special status and became part of Galicia.

At the same time, the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) people in eastern Galicia started to develop a stronger sense of their own national identity. A group of activists, mainly Greek Catholic students, began to focus on the common people and their language. In 1837, they published a collection of folk songs in Ukrainian. The Austrian government and church leaders were worried by this and banned the book.

In 1848, revolutions broke out across the Austrian Empire. In Lviv, both Polish and Ukrainian councils were formed. Even before Vienna acted, the governor ended serfdom to prevent more unrest. Poles wanted Galicia to be more independent, while Ruthenians wanted equal rights and for the province to be split into a Polish west and a Ukrainian east. Eventually, the revolution was crushed.

For the next ten years, Austria ruled strictly again. To calm the Poles, Count Agenor Goluchowski, a Polish noble, was made governor. He started to make the local government more Polish and stopped the idea of dividing the province. However, he could not force the Greek Catholic Church to use the Western calendar or make Ruthenians use the Latin alphabet instead of Cyrillic.

Steps Towards Self-Rule

In 1859, after Austria lost a war in Italy, the empire started trying out new ways of governing. In 1860, the government in Vienna suggested giving more power to different regions, but this idea was changed. Still, by 1861, Galicia got its own law-making assembly, called the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria. At first, many Ukrainian and Polish peasants were part of this assembly, and they discussed important social issues. However, the Polish nobles soon gained control, and they wanted more self-rule for Galicia.

By 1863, a revolt began in Russian Poland, and it affected Galicia too. From 1864 to 1865, the Austro-Hungarian government declared a state of emergency in Galicia, temporarily stopping people's freedoms.

In 1865, the idea of giving more power to regions came back, and Polish nobles started talking with Vienna about Galicia's self-rule again.

Meanwhile, the Ruthenians felt more and more ignored by Vienna. Some, called Russophiles, started looking towards Russia. Others, influenced by Ukrainian writers, formed a movement that published books in Ukrainian and set up reading clubs. These people became known as Populists, and later, as Ukrainians. Most Ruthenians still hoped for equal rights and for Galicia to be divided into a Polish west and a Ukrainian east.

Galicia Gains Autonomy

In 1866, after Austria lost the Austro-Prussian War, the Austro-Hungarian Empire faced more internal problems. To get more support, Emperor Franz Joseph started talks with the Hungarian nobles. Some government officials wanted to create a federal system that would include all nationalities, but the Emperor could not ignore the powerful Hungarian nobles, who wanted a dual monarchy.

Finally, in February 1867, the Austrian Empire became the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Even though plans for other parts of the monarchy to have more freedom failed, Austrian rule in Galicia slowly became more liberal. Polish nobles and thinkers asked the Emperor for more self-rule for Galicia. Their demands were not fully met at once, but over the next few years, Galicia gained more and more autonomy.

From 1873, Galicia was mostly a self-governing province of Austria-Hungary. Polish and, to a lesser extent, Ukrainian were made official languages. The effort to make everyone speak German stopped, and censorship was lifted. Galicia was part of the Austrian side of the dual monarchy, but the Galician Sejm (parliament) and local government had many special rights, especially in education, culture, and local matters.

Many Polish thinkers supported these changes. A group of young conservative writers in Kraków published a series of pamphlets in 1869. They made fun of the idea of armed uprisings and suggested working with Austria. They also focused on growing the economy and accepting the political freedoms offered by Vienna. This group became known as the Kraków Conservatives. Along with Polish landowners from eastern Galicia, they gained political power in Galicia that lasted until 1914.

This shift in power from Vienna to the Polish landowning class was not welcomed by the Ruthenians. They became more divided into Ukrainophiles, who looked to Kyiv for historical ties, and Ukrainians, who focused on their connection to the common people.

Both Vienna and the Poles saw the Russophiles as disloyal, and a series of trials eventually weakened their influence. By 1890, an agreement was made between the Poles and the "Populist" Ruthenians (Ukrainians). This led to more Ukrainian language in schools in eastern Galicia and other support for Ukrainian culture. As a result, the number of Ukrainian language students increased greatly. The Ukrainian national movement quickly grew among the Ruthenian peasants. Even with difficulties, by the early 1900s, this movement had largely replaced other Ruthenian groups as the main challenge to Polish power. Throughout this time, Ukrainians continued to demand equal rights and for the province to be split into a Polish west and a Ukrainian east. Starting in 1895, elections in Galicia became known for being "bloody" because the Austrian prime minister, Count Kasimir Felix Badeni, rigged the results and had police beat voters who did not vote for the government.

Mass Emigration for a Better Life

Starting in the 1880s, many peasants from Galicia began to leave the region. At first, they went to Germany for seasonal work. Later, many moved across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States, Brazil, and Canada.

This mass emigration happened because Galicia was very poor, and poverty in the countryside was widespread. The movement started in the western, Polish-speaking part of Galicia and then spread east to the Ukrainian-speaking areas. Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, and Germans all took part in this large movement of people. Poles mainly went to the United States and Brazil, while Ruthenians/Ukrainians went to Brazil, Canada, and the United States. Many Jews also moved to the New World. Most Ukrainians and Poles who came to Canada before 1914 were from Galicia or the nearby Bukovina province.

There were also famines in Galicia in 1847, 1849, 1855, 1865, 1876, and 1889, which caused thousands to die from starvation. This made people feel that life in Galicia was hopeless and encouraged them to leave for a better life. Also, new inheritance laws in 1868 meant that land was divided equally among sons. Since Galician peasants often had large families, the land became too small to farm profitably.

Hundreds of thousands of people were part of this "Great Economic Emigration." It grew stronger until World War I started in 1914, which temporarily stopped it. This emigration was described in books by Polish and Ukrainian writers. Some areas in southern Brazil today have many people who are direct descendants of these Ukrainian immigrants.

Galicia was one of the least developed areas in the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Peasants in Galicia were often on the edge of starvation. This led Polish peasants to call the area "Krolestwo Goloty i Glodomerji," meaning "The Kingdom of Bareness and Starvation." While serfdom was banned in the Russian Empire in the 1870s, in Galicia, peasants could still be forced back into a similar situation by wealthy Polish merchants and nobles until World War I.

Despite almost 750,000 people leaving across the Atlantic between 1880 and 1914, Galicia's population still grew by 45% from 1869 to 1910.

World War I and Its Aftermath

During World War I, Galicia saw intense fighting between Russian forces and the Central Powers. The Imperial Russian Army took over most of the region in 1914. However, German and Austro-Hungarian forces pushed them out in 1915.

In late 1918, Eastern Galicia became part of the newly restored Second Polish Republic. However, the local Ukrainian population briefly declared Eastern Galicia independent as the West Ukrainian People's Republic. During the Polish–Soviet War, the Soviets tried to create a puppet state called the Galician SSR in East Galicia, but its government was soon dissolved.

The future of Galicia was decided by the Peace of Riga on March 18, 1921, which gave all of Galicia to the Second Polish Republic. Although some Ukrainians did not accept this, it was recognized internationally in 1923, partly due to French support. France supported Polish rule in eastern Galicia because of its oil resources. In return, Poland allowed French companies to invest heavily in the Galician oil industry. The Poles convinced the French that only they could manage eastern Galicia and its oil, as most Ukrainians were not educated enough to govern themselves.

Ukrainians from former eastern Galicia and the nearby province of Volhynia made up about 12% of the population of the Second Polish Republic. As the Polish government's policies were often unfriendly towards minorities, tensions grew between the government and the Ukrainian people. This eventually led to the rise of the militant underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.

Administrative Divisions

After the first partition of Poland, the newly acquired Polish territories were reorganized in November 1773 into 59 districts. Some former Polish regions were fully included, while most were only partly. These included parts of the former regions of Belz, Red Ruthenia, Cracow, Lublin, Sandomierz, and Podolie. Also, during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) in 1769, the northwestern part of Moldavia (renamed Bukovina) was taken by Russia, which then gave it to the Austrian Empire in 1774.

Major Cities and Towns

The Kingdom was divided into many counties, about 75 in 1914. Lviv was the capital of the Kingdom. Kraków was seen as the unofficial capital of western Galicia and the second most important city.

- Belz (Polish: Bełz)

- Berezhany (Polish: Brzeżany)

- Biecz

- Bochnia

- Boryslav (Polish: Borysław)

- Brody

- Busk

- Buchach (Polish: Buczacz)

- Chortkiv (Polish: Czortkow)

- Chrzanów

- Dukla

- Drohobych (Polish: Drohobycz)

- Gorlice

- Halych (Polish: Halicz)

- Husiatyn

- Jarosław

- Jasło

- Kalush (Polish: Kałusz)

- Kolomyia (Polish: Kołomyja)

- Kozova (Polish: Kozowa)

- Kraków

- Krosno

- Lesko

- Leżajsk

- Limanowa

- Lviv (Polish: Lwów)

- Łańcut

- Myślenice

- Nadvirna (Polish: Nadwórna)

- Nowy Sącz

- Oświęcim (German: Auschwitz)

- Peremyshliany (Polish: Przemyślany)

- Przemyśl

- Pidhaytsi (Polish: Podhajce)

- Rava-Ruska

- Rohatyn

- Rymanów

- Rzeszów

- Sambir (Polish: Sambor)

- Sanok

- Stanyslaviv (Polish: Stanisławów)

- Terebovlia (Polish: Trembowla)

- Ternopil' (Polish: Tarnopol)

- Tarnów

- Tomaszów Lubelski

- Truskavets (Polish: Truskawiec)

- Wieliczka

- Zalishchyky (Polish: Zaleszczyki)

- Zator

- Zolochiv (Polish: Złoczów)

- Zhovkva (Polish: Żółkiew)

- Żywiec

Government and Leadership

After Poland was divided, Galicia was ruled by an appointed governor. Later, this role was called a vice-regent. During wartime, a military governor also helped. In 1861, a regional assembly, the Sejm of the Land, was created. It met in the Skarbek Theatre until 1890.

Vice-Regents of Galicia

Here are some of the vice-regents from 1900 onwards:

- Count Leon Piniński (1898–1903)

- Count Andrzej Potocki (1903–1908)

- Count Michał Bobrzyński (1908–1913)

- Witold Korytowski (1913–1915)

- Russian occupation (September 1914 – 1915)

- Hermann von Colard (1915–1916)

- Baron Erich von Diller (1916–1917), exiled during Russian occupation

- Russian occupation (1916 – July 1917)

- Count Karl Georg Huyn (1917–1918)

Political Groups and Organizations

Many political and public groups were active in Galicia:

Political Groups

- Chief Ruthenian Council (1848–1851): Led by Gregory Yakhimovich, it had 30 members.

- Ruthenian Council (Lviv) (1870–1914)

- Ruthenian Congress (1848): An opposing group to the Chief Ruthenian Council.

- Ukrainian National Democratic Party (1899–1919): Later became part of the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance.

- Ukrainian Radical Party (1890–1939)

- Christian-Social Party (1896–1930): Focused on Catholic-Ruthenian people.

- Ukrainian Social Democratic Party (1899–1939)

- Ukrainian General Council (1914–1916): A group of most Ukrainian parties that helped set up the Ukrainian state in West Ukraine.

Public Organizations

- Ukrainian Forum (Besida) (1861–1939): An association that created its own Ukrainian theater.

- Prosvita (1868–present): An educational society.

- Shevchenko Scientific Society (1873–present): A scientific and cultural organization.

- Ruthenian Triad (1833–1843): A literary group.

- Academic Society (Hromada) (1882–1921)

- Sokół and Sokil sport organizations: Part of a larger European movement.

- Sich and Plast: Youth organizations.

- Luh: A fireman society.

- Riflemen's Association

People of Galicia

In 1773, Galicia had about 2.6 million people living in cities, towns, and villages. About 3% of the population were nobles. More than 70% of the people were "non-free," meaning they were like servants or had very little land.

Galicia had a very diverse mix of people: Poles, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Germans, Armenians, Jews, Hungarians, Romani people, and others. Poles mostly lived in the west, while Ruthenians (Ukrainians) were more common in the eastern region.

The Jews of Galicia had moved there from Germany in the Middle Ages and mostly spoke Yiddish. German-speaking people were often called "Saxons" or "Swabians," even if they weren't from those specific German regions. It was easier to tell people apart by their religion: most Poles were Latin Catholics, while Ruthenians were mostly Greek Catholics. Jews, the third largest religious group, followed traditional Jewish practices. The Jewish community in Galicia felt a strong connection to the region and called themselves Galitzianer.

Life in Galicia was tough. The average life expectancy was only 27 years for men and 28.5 years for women, much lower than in other parts of Europe. Galicia was the poorest province in the Austrian Empire. People ate very little meat, only about 10 kg per person per year, compared to 33 kg in Germany. This was because incomes were very low. In the 19th century, poverty in Galicia was so bad that people called it "Golicja and Glodomeria," a play on its name meaning "nakedness and starvation."

In 1888, Galicia covered about 78,550 square kilometers and had about 6.4 million people. Most of them (75%) were peasants. The population density was high, with 81 people per square kilometer. The population grew to 7.3 million by 1900 and 8 million by 1910.

| Religion | Number of People | |

|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 3,731,569 | 46.5% |

| Greek Catholic (Uniates) | 3,379,613 | 42.1% |

| Jewish | 871,895 | 10.9% |

| Protestant | 37,144 | 0.5% |

| Other | 5,454 | <0.1% |

| Total | 8,025,675 | |

Economy of Galicia

Galicia was the least developed part of Austria and received a lot of money from the government in Vienna. Its economy was similar to or better than Russia and the Balkans, but far behind Western Europe.

A Polish economist named Stanislaw Szczepanowski wrote a detailed report in 1873 called The Galician Poverty in Numbers. He used his own experiences and government data to show that Galicia was one of the poorest regions in Europe.

Statistics showed that Galicia and Lodomeria was poorer than areas to its west. The average income per person was very low. Taxes were also high, about 17% of yearly income. Despite high taxes, the government of Galicia always had a large debt.

Overall, the Austro-Hungarian government mainly used Galicia as a source of cheap workers and soldiers, and as a protective area against Russia. It wasn't until the early 20th century that heavy industries began to develop, mostly for war production. The biggest government investments were in railways and fortresses in cities like Przemyśl and Kraków. Other industries included private oil companies and the famous Wieliczka salt mine, which had been operating since the Middle Ages.

Oil and Natural Gas Industry

Near Drohobych and Boryslav in Galicia, large amounts of oil were found and developed in the mid-19th and early 20th centuries. The first attempt to drill for oil in Europe was in Bóbrka in western Galicia in 1854. By 1867, a well was drilled to about 200 meters using steam. In 1872, a railway line connected Borysław with Drohobycz.

American John Simon Bergheim and Canadian William Henry McGarvey came to Galicia in 1882. Their company found huge oil deposits by drilling deep holes. In 1885, they renamed their company the Galician-Karpathian Petroleum Company and built a large refinery near Gorlice. This refinery was considered the biggest and most efficient in Austria-Hungary. Later, investors from Britain, Belgium, and Germany also started oil and natural gas companies in Galicia.

This led to a decrease in the number of oil companies but an increase in oil refineries. By 1904, there were many deep oil wells in Borysław. Oil production increased by 50% between 1905 and 1906, and then tripled between 1906 and 1909 due to new discoveries. By 1909, production reached its highest point, making up 4% of the world's oil production. The oil fields of Borysław and Tustanowice produced over 90% of the Austro-Hungarian Empire's oil. Borysław grew from 500 residents in the 1860s to 12,000 by 1898. In 1909, a company called Polmin was created in Lviv to extract and distribute natural gas. Around 1900, Galicia was the fourth-largest oil producer in the world. This big increase in oil also caused oil prices to drop. Oil production in Galicia decreased sharply just before the Balkan Wars.

Galicia was the only major source of oil for the Central Powers during World War I.

Culture and Media

- Newspapers: Gazette de Leopol (started 1776), Slovo (closed 1876).

- Weekly: Zoria Halytska (first issue May 15, 1848).

Flags of Galicia

Until 1849, Galicia and Lodomeria was one province with Bukovina and used a blue-red flag (two horizontal stripes: blue on top, red on bottom).

In 1849, Bukovina became independent from Galicia-Lodomeria and kept the blue-red flag. Galicia received a new flag with three horizontal stripes: blue, red, and yellow.

That flag was used until 1890. Then, Galicia-Lodomeria got another new flag with two horizontal stripes: red and white. This flag was used until the Kingdom of Galicia-Lodomeria ended in 1918.

Military Forces

The Kingdom was divided into three main military areas: Kraków, Lviv, and Przemyśl. The local military used a special language called Army Slav for communication. One important army unit was the 1st Army.

Selected Military Units (1914)

Many Lancer (cavalry) regiments were based in Galicia. Their command language was German, but many soldiers spoke Polish or Ukrainian.

- 1st Galicia Lancer Regiment: Mostly Poles (85%).

- 2nd Galicia Lancer Regiment: Mostly Poles (84%).

- 3rd Galicia Lancer Regiment: Poles (69%) and Ukrainians (26%).

- 4th Galicia Lancer Regiment: Ukrainians (65%) and Poles (29%).

- 6th Galicia Lancer Regiment: Poles (52%) and Ukrainians (40%).

- 7th Galicia Lancer Regiment: Mostly Ukrainians (72%).

- 8th Galicia Lancer Regiment: Mostly Poles (80%).

- 13th Galicia Lancer Regiment: Ukrainians (55%) and Poles (42%).

- 1st Army Lancer Regiment: Ukrainians (65%) and Poles (30%).

- 3rd Army Lancer Regiment: Poles (69%) and Ukrainians (26%).

- 4th Army Lancer Regiment: Mostly Poles (85%).

One Dragoon (cavalry) regiment:

- 9th Galicia-Bukowina Dragoon Regiment: Romanians (50%) and Ukrainians (29%).

Ten Infantry regiments:

- 16th Army Infantry Regiment "Krakau": Mostly Poles (82%).

- 17th Army Infantry Regiment "Rzeszów": Mostly Poles (97%).

- 18th Army Infantry Regiment "Przemyśl": Ukrainians (47%) and Poles (43%).

- 19th Army Infantry Regiment "Lemberg": Ukrainians (59%) and Poles (31%).

- 20th Army Infantry Regiment "Stanislau": Mostly Ukrainians (72%).

- 32nd Army Infantry Regiment (Tarnów): Mostly Poles (91%).

- 33rd Army Infantry Regiment (Stryi): Mostly Ukrainians (73%).

- 34th Army Infantry Regiment (Jarosław): Mostly Poles (75%).

- 35th Army Infantry Regiment (Zolochiv): Ukrainians (68%) and Poles (25%).

- 36th Army Infantry Regiment (Kolomea): Ukrainians (70%) and Poles (21%).

Two Artillery divisions:

- 43rd Field Artillery Division (Lviv): Ukrainians (55%) and Poles (25%).

- 45th Field Artillery Division (Przemyśl): Ukrainians (60%) and Poles (25%).

Five Feldjäger (Military Police) battalions:

- 4th Galicia Feldjäger Battalion (Rzeszow district): Mostly Poles (77%).

- 12th Bohemia Feldjäger Battalion (Kraków district): Czech (67%) and German (32%).

- 14th Feldjäger Battalion (Przemyśl district): Ukrainians (47%) and Poles (43%).

- 18th Feldjäger Battalion (Lviv district): Ukrainians (59%) and Poles (31%).

- 30th Galicia-Bukowina Feldjäger Battalion (Stanislav district): Mostly Ukrainians (70%).

Other military units:

- 10th Engineer Battalion (Przemyśl): Poles (50%) and Ukrainians (30%).

- 1st Sapper Battalion (Krakau): Poles (50%), Germans (23%), and Czechs (23%).

- 10th Sapper Battalion (Przemyśl): Poles (50%) and Ukrainians (30%).

- 11th Sapper Battalion (Lemberg): Ukrainians (48%) and Poles (32%).

- Polish Legions

- Ukrainian Legions

- 1st Ukrainian Cossack Rifle Division (1918)

The Legacy of Galicia

In 2014, a Polish historian named Jacek Purchla noted two main ways people remember Galicia. One way is as a peaceful, multi-cultural land from a simpler, better time. The other is how Austrians saw it as "half-Asia," a "barbaric place" with "strange people." Austria always saw Galicia as a colony that needed to be "civilized" and not truly part of Austria.

Both Polish and Ukrainian people in Galicia saw the province as their "Piedmont." This refers to the Italian region where Italy's fight for independence began. So, Polish and Ukrainian nationalists felt that their own countries' freedom would start in Galicia. This memory of Galicia under Austrian rule is a big part of both Polish and Ukrainian national identities. For example, the Ukrainian parts of Galicia played a key role in the Maidan revolution in Ukraine.

Starting in the late 19th century, about 2 million Galician Jews moved to the United States. Among their descendants, the memory of Galicia as either a lost paradise or a difficult place to escape from is still alive. The Economist reported that "In Europe, Galicia is a central element of Poles’ national identity and of Ukrainians’ search for a European identity."

Images for kids

-

Map of a region where Ruthenians and Russians lived in the Austrian Empire – Galicia and Hungarian Russia (Carpathian Ruthenia) – by Dmitry Vergun

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Galitzia y Lodomeria para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Galitzia y Lodomeria para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |

![Coat of arms [pl; uk] of Galicia and Lodomeria](/images/thumb/2/22/Coat_of_arms_of_the_Kingdom_of_Galicia_and_Lodomeria.svg/85px-Coat_of_arms_of_the_Kingdom_of_Galicia_and_Lodomeria.svg.png)