Nicholas I of Russia facts for kids

Nicholas I (born 6 July 1796 – died 2 March 1855) was the Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland. He was the third son of Emperor Paul I and the younger brother of Emperor Alexander I, who ruled before him. Nicholas's time as ruler began with a failed uprising called the Decembrist revolt. He is mostly remembered as a very strict ruler who expanded Russia's lands, made the government more centralized, and stopped people from disagreeing with him. Nicholas had a happy marriage and a large family, with all seven of his children surviving childhood.

Nicholas's biographer, Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, described him as a determined and strong-willed leader. He had a powerful sense of duty and worked very hard. Nicholas saw himself as a soldier, always focused on details. He was trained as a military engineer and paid close attention to small things. In public, Nicholas I was seen as the perfect example of an absolute ruler: grand, powerful, and unyielding.

Nicholas I played a key role in helping Greece become an independent country. He also continued Russia's expansion into the Caucasus region, taking control of parts of modern-day Armenia and Azerbaijan from Persia during the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828). He also won the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29). However, later in his reign, he led Russia into the Crimean War (1853–1856), which ended badly for Russia. Historians say that he tried to control his armies too much, which made it hard for his generals. William C. Fuller noted that many historians believe Nicholas I's rule was a "catastrophic failure" in both Russia and its dealings with other countries. When he died, the Russian Empire was at its largest, covering over 20 million square kilometers (about 7.7 million square miles), but it desperately needed changes.

Quick facts for kids Nicholas I |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

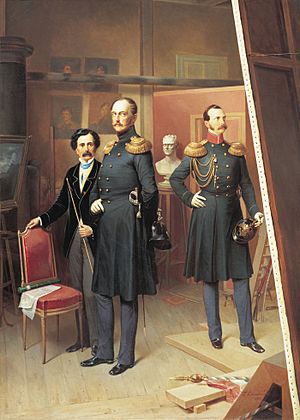

Portrait by Georg von Bothmann, 1855

|

|||||

| Emperor of Russia | |||||

| Reign | 1 December 1825 – 2 March 1855 | ||||

| Coronation | 3 September 1826 | ||||

| Predecessor | Alexander I | ||||

| Successor | Alexander II | ||||

| Born | 6 July 1796 Gatchina Palace, Gatchina, Russian Empire |

||||

| Died | 2 March 1855 (aged 58) Winter Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

||||

| Burial | Peter and Paul Cathedral, St. Petersburg, Russian Empire | ||||

| Spouse |

Charlotte of Prussia

(m. 1817) |

||||

| Issue |

|

||||

|

|||||

| House | Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp | ||||

| Father | Paul I of Russia | ||||

| Mother | Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Contents

Nicholas I's Early Life and Rise to Power

Nicholas was born at Gatchina Palace in Gatchina. He was the ninth child of Grand Duke Paul, who was next in line to the Russian throne, and Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna. He had six older sisters and two older brothers, including the future Emperor Alexander I and Grand Duke Constantine.

Five months after Nicholas was born, his grandmother, Catherine the Great, died. His parents then became the Emperor and Empress of Russia. In 1800, when he was four, Nicholas was given the title of Grand Prior of Russia and allowed to wear the Maltese cross. Nicholas grew into a handsome young man. Riasanovsky described him as "the most handsome man in Europe."

On 13 July 1817, Nicholas married Princess Charlotte of Prussia. She took the name Alexandra Feodorovna when she joined the Orthodox Church. Charlotte's parents were Frederick William III of Prussia and Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Nicholas and Charlotte were third cousins, meaning they shared great-great-grandparents.

With two older brothers, it seemed unlikely Nicholas would ever become Tsar. However, Alexander and Constantine both did not have sons who could legally inherit the throne. This meant Nicholas became the likely future ruler, or at least his children would. In 1825, Alexander I died suddenly from typhus. Nicholas was then in a difficult spot, unsure whether to promise loyalty to Constantine or accept the throne himself. This period of uncertainty lasted until Constantine, who was in Warsaw, confirmed he did not want to rule.

On 25 December, Nicholas announced that he was taking the throne. This announcement said his reign had begun on 1 December, the day Alexander I died. During this confusion, some military officers planned to overthrow Nicholas and take power. This led to the Decembrist Revolt on 26 December 1825. Nicholas quickly stopped this uprising.

Becoming Emperor and His Rules

First Years as Emperor

Nicholas was not as open-minded as his brother. He saw his role simply as an absolute ruler who would govern his people in any way he felt was necessary. Nicholas I began his reign on 14 December 1825. This day was a Monday, which Russian superstitions considered unlucky. It was also very cold, with temperatures of -8 degrees Celsius. Russians saw this as a bad sign for his rule.

Nicholas I's start as emperor was marked by a protest from 3,000 young army officers and other liberal citizens. They wanted the government to accept a constitution and a representative government. Nicholas ordered the army to stop the protest. This "uprising" was quickly put down and became known as the Decembrist Revolt.

After the shock of the Decembrist Revolt on his very first day, Nicholas I was determined to control Russian society. He created the Third Section of the Imperial Chancellery. This was a large network of spies and informers, helped by the Gendarmes (a type of police force). The government also controlled education, publishing, and all public life through strict censorship. Nicholas appointed Alexander Benckendorff to lead this Third Section. Benckendorff had 300 gendarmes and 16 staff. He started gathering informers and reading people's mail at a fast rate. Soon, people joked that you couldn't even sneeze in your house without the emperor knowing about it, which became Benckendorff's motto.

Changes in Russia

Tsar Nicholas removed several areas of local self-rule. Bessarabia's self-rule was taken away in 1828, Poland's in 1830, and the Jewish Qahal (community council) was ended in 1843. However, Finland was allowed to keep some of its self-rule. This was partly because Finnish soldiers helped put down the November Uprising in Poland.

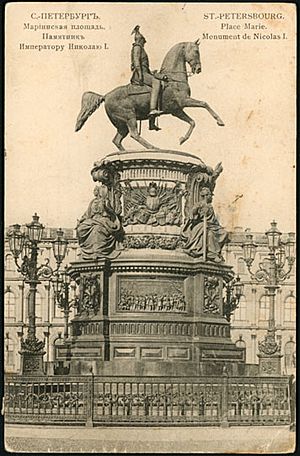

Russia's first railway opened in 1837. It was a 16-mile (26 km) line between St. Petersburg and the royal residence of Tsarskoye Selo. The second railway, between Saint Petersburg and Moscow, was built from 1842 to 1851. Even so, by 1855, Russia only had about 570 miles (917 km) of railways.

In 1833, Sergey Uvarov, from the Ministry of National Education, created a program called "Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality." This became the main idea for Nicholas's rule. It was a strict policy based on:

- Orthodoxy in religion (meaning loyalty to the Russian Orthodox Church).

- Autocracy in government (meaning the tsar had unlimited power).

- Nationality (meaning the Russian people had a special role in the state, and all other peoples in Russia had equal citizen rights, except for Jews).

People were expected to be loyal to the tsar's absolute power, to the traditions of the Russian Orthodox Church, and to the Russian language. These ideas led to more control over all parts of society. There was also too much censorship and spying on independent thinkers like Pushkin and Lermontov. Non-Russian languages and non-Orthodox religions were also treated badly. Taras Shevchenko, who later became Ukraine's national poet, was sent away to Siberia by a direct order from Tsar Nicholas. This happened after he wrote a poem that made fun of the Tsar, his wife, and his policies. The Tsar ordered that Shevchenko be watched closely and stopped from writing or painting.

From 1839, Tsar Nicholas also used a former Byzantine Catholic priest named Joseph Semashko to force Orthodox beliefs on Eastern Rite Catholics in Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania. This led to many leaders, including Popes, and Western governments criticizing Tsar Nicholas.

Nicholas did not like serfdom (a system where peasants were tied to the land and owned by nobles). He thought about ending it in Russia but decided not to because he feared the powerful noble families. He believed they might turn against him if he freed the serfs. However, he did try to make life better for the Crown Serfs (serfs owned by the government) with the help of his minister Pavel Kiselyov. During most of his reign, he tried to increase his control over landowners and other powerful groups in Russia. In 1831, Nicholas limited voting in the Noble Assembly to only those who owned more than 100 serfs. In 1841, nobles who didn't own land were not allowed to sell serfs separately from the land. From 1845, a person needed to reach the 5th highest rank in the Table of Ranks (out of 14) to become a noble. Before this, it was the 8th rank.

King of Poland

Nicholas was crowned King of Poland in Warsaw on 12 May 1829. This was done according to the Polish Constitution, a document he would not respect later. He is the only Russian monarch ever crowned King of Poland.

Culture and Ideas

The government's focus on Russian nationalism caused a debate about Russia's place in the world, its history, and its future. One group, called the westernizers, believed Russia was behind and could only improve by becoming more like Europe. Another group, the Slavophiles, strongly supported Slavic people, their culture, and customs. They disliked Westerners and their ways.

The Slavophiles saw Slavic ideas as a source of strength for Russia. They were doubtful of Western ways of thinking and focus on money. Some believed that the Russian peasant community, or Mir, offered a better way of life than Western capitalism. They thought Russia could become a moral leader for the world. However, the Ministry of Education had a policy of closing philosophy departments because they feared these ideas could be harmful.

After the Decembrist revolt, the tsar worked to keep things as they were by centralizing the education system. He wanted to stop foreign ideas and what he called "false knowledge." However, his minister of education, Sergei Uvarov, quietly supported academic freedom. He also improved academic standards, facilities, and allowed middle-class students to attend higher education. By 1848, the tsar became worried that political uprisings in the West might inspire similar revolts in Russia. So, he ended Uvarov's changes. Universities were small and closely watched, especially the philosophy departments, which were seen as potentially dangerous. Their main goal was to train loyal, strong government officials who avoided desk work.

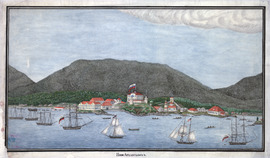

The Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg became more important as it recognized and supported artists. Nicholas I decided to control it himself. He would overrule decisions about giving ranks to artists. He would scold and embarrass artists whose work he didn't like. This did not lead to better art. Instead, it created fear and uncertainty among artists.

Despite the strict controls of this time, Russians outside official control created many great works of literature and art. Through the writings of Aleksandr Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, and others, Russian literature became famous worldwide. Ballet became popular in Russia after being brought from France. Classical music also became well-known with the works of Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857).

Finance Minister Georg von Cancrin convinced the emperor to invite the Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt to Russia. Humboldt was to explore regions that might have valuable minerals. The Russian government paid for Humboldt's eight-month trip through Russia in 1829. This trip led to the discovery of diamonds in the Ural mountains. Humboldt published many books about his Russian journey, dedicating them to the tsar, even though he increasingly disagreed with the tsar's policies.

Treatment of Jewish People

In 1851, there were 2.4 million Jewish people in Russia, with 212,000 living in Russian-controlled Poland. This made them one of the largest minority groups in the Russian Empire.

On 26 August 1827, a new law for military service was introduced. It required Jewish boys to serve in the Russian military for 25 years starting at age 18. Before that, many were forced into Cantonist schools from age 12. Time in these schools did not count towards military service. They were sent far from their families to serve in the military so they would have trouble practicing their religion and become more like Russians. Poorer Jewish people, those without families, and unmarried Jewish people were especially targeted for military service. Between 1827 and 1854, it's estimated that 70,000 Jewish people were forced into the military. Some of them, without family or community support, were pressured to convert to Christianity.

Under Nicholas I, Jewish farming settlements in Ukraine continued. Jewish people were given land in Ukraine but had to pay for it, leaving them with little money to support their families. However, these Jewish settlers were exempt from forced military service.

Nicholas I also tried to change Jewish education to make Jewish people more like Russians. Studying the Talmud was discouraged because it was seen as a text that kept Jewish people separate from Russian society. Nicholas I made censorship of Jewish books in Yiddish and Hebrew even stricter. These books could only be printed in Zhitomir and Vilna.

Military and Foreign Policy

Nicholas's foreign policy involved many expensive wars, which badly affected Russia's money. Nicholas paid a lot of attention to his very large army. Out of a population of 60–70 million people, the army had one million men. Their equipment and tactics were old, but the tsar, who dressed like a soldier, was proud of the victory over Napoleon in 1812. He loved how smart his army looked on parade. For example, the cavalry horses were only trained for parades and did not do well in real battles. The fancy uniforms and decorations hid serious weaknesses that Nicholas did not see. He put generals in charge of most of his civilian government departments, even if they weren't qualified. For example, a general who was good at cavalry charges was put in charge of Church affairs.

The army became a way for young nobles from non-Russian areas like Poland, the Baltic, Finland, and Georgia to move up in society. On the other hand, many troublemakers, small criminals, and unwanted people were punished by local officials by being forced to join the army for life. The system of forcing people into the army was very unpopular. People also disliked having to house soldiers for six months of the year. Historian Curtiss found that "Nicholas's military system, which focused on blind obedience and parade drills instead of combat training, created ineffective commanders during wartime." His commanders in the Crimean War were old and not good at their jobs. Even their muskets were outdated because colonels often sold the best equipment and food for themselves.

For much of Nicholas's reign, Russia was seen as a major military power. The Crimean War, fought shortly before Nicholas died, showed Russia and the world what few had realized: Russia was militarily weak, technologically behind, and poorly managed. Despite his big plans for the south and Turkey, Russia had not built a railway network in that direction, and communication was bad. The government was not ready for war and was full of bribery, corruption, and inefficiency. The Navy had few good officers, the regular sailors were poorly trained, and most of its ships were old. The Army, though very large, was only good for parades. It suffered from colonels who stole their men's pay, low morale, and was even further behind in new technology compared to Britain and France. By the end of the war, Russia's leaders were determined to change their military and society. As Fuller noted, "Russia had been defeated in the Crimean peninsula, and the military feared that it would surely be defeated again unless steps were taken to overcome its military weakness."

Nicholas was often frustrated by how slow the Russian government worked. He preferred to appoint generals and admirals to high government positions because he thought they were efficient. He often ignored whether they were actually qualified for the job. Of the men who served as Nicholas's ministers, 61% had been a general or an admiral before. Nicholas liked to appoint generals who had fought in battles. At least 30 of his ministers had seen action in wars against France, the Ottoman Empire, and Sweden. This was a problem because the qualities that made a man brave in battle did not necessarily make him good at running a government department. The most famous example was Prince Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov, a good army commander who was completely out of his depth as Navy minister. Of the Emperor's ministers, 78% were ethnic Russians, 9.6% were Baltic Germans, and the rest were foreigners serving Russia. Of the men who served as ministers under Nicholas, 14 had graduated from university, and another 14 had graduated from a lycée or a gymnasium (types of secondary schools). The rest had all been taught by private tutors.

Europe

In foreign policy, Nicholas I saw himself as the protector of traditional rulers and a guard against revolutions. He often worked with the Austrian leader Klemens von Metternich to stop revolutions. Nicholas offered to stop revolutions across Europe, trying to follow his older brother Alexander I's example. This earned him the nickname "gendarme of Europe" (Europe's policeman).

As soon as he became emperor, Nicholas began to limit the freedoms that existed under the constitutional monarchy in Congress Poland. Nicholas was very angry when he heard about the Belgian revolt against the Dutch in 1830. He ordered the Russian Army to get ready. Nicholas then asked the Prussian ambassador for permission for Russian troops to march across Europe to restore Dutch rule over Belgium. But at the same time, a cholera epidemic was weakening the Russian Army, and the revolt in Poland kept Russian soldiers busy who might have been sent against the Belgians. It seems Nicholas's strong stance was not a real plan to invade the Low Countries, but rather an attempt to put pressure on other European powers. Nicholas made it clear he would only act if Prussia and Britain also joined, as he feared a Russian invasion of Belgium would cause a war with France. Even before the Poles revolted, Nicholas had canceled his plans for invading Belgium because it was clear that neither Britain nor Prussia would join, and the French openly threatened war if Nicholas marched.

In 1815, Nicholas visited France and stayed with the duc d'Orleans, who became one of his best friends. Nicholas was impressed by the duc's kindness, intelligence, and manners. For Nicholas, the worst kind of nobles were those who supported liberal ideas. So, when the duc d'Orleans became the King of the French as Louis Philippe I in the July Revolution of 1830, Nicholas felt personally betrayed. He believed his friend had joined what he saw as the "dark side" of revolution and liberalism. Nicholas hated Louis-Philippe, who called himself Le roi citoyen ("the Citizen King"), seeing him as a disloyal noble and a "usurper." From 1830, Nicholas's foreign policy was mainly anti-French. He wanted to bring back the alliance that existed during the Napoleonic Era: Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Britain, to isolate France. Nicholas disliked Louis-Philippe so much that he refused to use his name, calling him only "the usurper." Britain was unwilling to join the anti-French alliance, but Nicholas successfully strengthened ties with Austria and Prussia. The three empires often held joint military reviews during this time. For much of the 1830s, a kind of "cold war" existed between the liberal "western bloc" of France and Britain versus the strict "eastern bloc" of Austria, Prussia, and Russia.

After the November Uprising broke out in Poland in 1831, the Polish parliament removed Nicholas as king of Poland. This was because he kept taking away their constitutional rights. Nicholas responded by sending Russian troops into Poland and brutally crushed the rebellion. Nicholas then largely canceled the Polish constitution and turned Poland into a province called Vistula Land. Soon after, Nicholas began to suppress Polish culture, starting with the Polish Catholic Church. In the 1840s, Nicholas reduced 64,000 Polish nobles to commoner status.

In 1848, when a series of revolutions swept across Europe, Nicholas was a leader in stopping them. In 1849, he helped the Habsburgs (the ruling family of Austria) put down the revolution in Hungary. He also urged Prussia not to adopt a liberal constitution.

Ottoman Empire and Persia

While Nicholas tried to keep things stable in Europe, he was more aggressive towards the neighboring empires to the south: the Ottoman Empire and Persia. At the time, many believed Nicholas was following Russia's traditional goal of dividing the Ottoman Empire and taking control of the Orthodox Christian people in the Balkans, who were still largely under Ottoman rule in the 1820s. However, Nicholas was actually very committed to keeping things stable in Europe. He feared that trying to take over the weakening Ottoman Empire would upset his ally Austria, which also had interests in the Balkans. It could also lead to Britain and France forming an alliance to defend the Ottomans.

In the war of 1828–29, the Russians defeated the Ottomans in every battle and advanced deep into the Balkans. But the Russians realized they didn't have enough supplies and support to capture Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

Nicholas's policy towards the Ottoman Empire was to use the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774). This treaty gave Russia a vague right to protect Orthodox people in the Balkans. Nicholas saw this as a way to bring the Ottoman Empire under Russian influence, which he felt was more achievable than conquering the entire empire. Nicholas actually wanted to keep the Ottoman Empire as a stable but weak state that couldn't stand up to Russia. He felt this served Russia's interests. Nicholas always thought of Russia as a European power first and believed Europe was more important than the Middle East.

The Russian Foreign Minister Karl Nesselrode wrote that if Muhammad Ali of Egypt defeated Mahmud II, it could lead to a new ruling family in the Ottoman Empire. Nesselrode believed that if the capable Muhammad Ali became sultan, it "could... revive new strength in that declining empire and distract our attention and forces from European affairs." So, Nicholas was especially concerned with keeping the current sultan on his shaky throne. At the same time, Nicholas argued that because the Turkish straits (important for Russia's grain exports) were economically vital, Russia had the "right" to get involved in Ottoman affairs. In 1833, Nicholas told the Austrian ambassador that "Oriental affairs are above all a matter for Russia." Yet, while claiming the Ottoman Empire was in Russia's sphere of influence, he made it clear he had no interest in taking over the empire. Nicholas said: "I know everything that has been said of the projects of the Empress Catherine, and Russia has given up the goal she had set out. I wish to maintain the Turkish empire... If it falls, I do not desire its debris. I need nothing." In the end, Nicholas's policies in the Near East were costly and mostly unsuccessful.

From 1826 to 1828, Nicholas fought the Russo-Persian War (1826–28). This war ended with Persia being forced to give up its last remaining lands in the Caucasus region. Russia had conquered all of Iran's territories in both the North and South Caucasus, including modern-day Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, during the 19th century. The treaty also gave Russian citizens in Iran special rights (extraterritoriality). As Professor Virginia Aksan noted, the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay "removed Iran from the military equation."

Russia fought a successful war against the Ottomans in 1828–29, but it did little to increase Russian power in Europe. Only a small Greek state became independent in the Balkans, with limited Russian influence. In 1833, Russia made the Treaty of Unkiar-Skelessi with the Ottoman Empire. Other European countries mistakenly believed that the treaty had a secret part that gave Russia the right to send warships through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits. This misunderstanding led to the London Straits Convention of 1841. This agreement confirmed Ottoman control over the straits and stopped any power, including Russia, from sending warships through them.

Feeling confident after helping to stop the revolutions of 1848, and mistakenly believing he had British diplomatic support, Nicholas moved against the Ottomans. The Ottomans declared war on Russia on 8 October 1853. On 30 November, Russian Admiral Nakhimov caught the Turkish fleet in the harbor at Sinope and destroyed it.

Fearing a complete Ottoman defeat by Russia, in 1854, Britain, France, and the Kingdom of Sardinia formed a military alliance and joined forces with the Ottoman Empire against Russia. This conflict became known as the Crimean War in the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe. In Russia, it was called the "Eastern War." In April 1854, Austria signed a defense agreement with Prussia. So, Russia found itself at war with every major European power, either militarily or diplomatically.

In 1853, Mikhail Pogodin, a history professor at Moscow University, wrote a memo to Nicholas. Nicholas himself read Pogodin's text and agreed, saying: "That is the whole point." According to historian Orlando Figes, "The memorandum clearly struck a chord with Nicholas, who shared Pogodin’s sense that Russia’s role as the protector of the Orthodox had not been recognized or understood and that Russia was unfairly treated by the West."

Austria offered the Ottomans diplomatic support, and Prussia remained neutral. This left Russia without any allies in Europe. The European allies landed in Crimea and surrounded the well-protected Russian Sevastopol Naval Base. The Russians lost battles at Alma in September 1854, and then at Balaklava and Inkerman. After a long Siege of Sevastopol (1854–55), the base fell. This showed Russia's inability to defend a major fort on its own land. When Nicholas I died, Alexander II became Tsar. On 15 January 1856, the new tsar pulled Russia out of the war on very unfavorable terms. This included losing a naval fleet on the Black Sea.

Death

Nicholas died on 2 March 1855, during the Crimean War, at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. He caught a cold, refused medical treatment, and died of pneumonia. He was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. He ruled for 30 years and was followed by his son, Alexander II.

Legacy

Many people have had very critical opinions about Nicholas's rule and what he left behind. Towards the end of his life, one of his most loyal government workers, A.V. Nikitenko, said, "the main failing of the reign of Nicholas Pavlovich was that it was all a mistake." In 1891, Lev Tolstoy helped popularize the nickname Николай Палкин (Nicholas the Stick). This referred to the very strict military discipline linked to the late emperor.

However, sometimes people try to improve Nicholas's reputation. Historian Barbara Jelavich, on the other hand, points to many failures. These include the "catastrophic state of Russian finances," the poorly equipped army, the inadequate transportation system, and a government system "which was characterized by graft, corruption, and inefficiency."

Kiev University was founded in 1834 by Nicholas. In 1854, there were 3,600 university students in Russia, which was 1,000 fewer than in 1848. Censorship was everywhere. Historian Hugh Seton-Watson wrote: "the intellectual atmosphere remained oppressive until the end of the reign."

As a traveler in Spain, Italy, and Russia, the Frenchman Marquis de Custine wrote in his popular book La Russie en 1839 (English translation: Empire of the Czar: A Journey Through Eternal Russia). He said that, deep down, Nicholas was a good person. He only acted the way he did because he believed he had to: "If the Emperor has no more of mercy in his heart than he reveals in his policies, then I pity Russia; if, on the other hand, his true sentiments are really superior to his acts, then I pity the Emperor."

Nicholas is part of a popular story about the Saint Petersburg–Moscow Railway. The story says that when the route was planned in 1842, he demanded the shortest path be used, even if there were big obstacles. The story claims he used a ruler to draw the straight line himself. This false story became popular both in Russia and abroad as an example of how badly Russia was governed. By the 1870s, Russians were telling a different version, saying the tsar was wise to overcome local interests that wanted the railway to go in different directions. What actually happened was that engineers planned the route, and Nicholas agreed with their advice to build it in a straight line.

Honours

| Styles of Nicholas I of Russia |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

- Knight of St. Andrew, 6 July 1797

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky, 6 July 1797

Kingdom of Prussia:

Kingdom of Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 31 January 1809

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle, 31 January 1809

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 4 September 1812

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 4 September 1812 Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 13 April 1817

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 13 April 1817 Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1823

Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1823 Kingdom of France: Knight of the Holy Spirit, 1824

Kingdom of France: Knight of the Holy Spirit, 1824 Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 24 January 1826

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 24 January 1826 Kingdom of Sardinia: Knight of the Annunciation, 15 April 1826

Kingdom of Sardinia: Knight of the Annunciation, 15 April 1826 Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Military William Order, 11 May 1826

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Military William Order, 11 May 1826 Austrian Empire: Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1826

Austrian Empire: Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1826 Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 3 November 1826

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 3 November 1826 Württemberg:

Württemberg:

- Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1826

- Grand Cross of the Military Merit Order, 6 October 1826

Two Sicilies:

Two Sicilies:

- Knight of St. Januarius, 1826

- Grand Cross of St. Ferdinand and Merit

- Grand Cross of St. George of the Reunion

United Kingdom: Knight of the Garter, 16 March 1827

United Kingdom: Knight of the Garter, 16 March 1827 Baden:

Baden:

- Grand Cross of the House Order of Fidelity, 1827

- Grand Cross of the Military Karl-Friedrich Merit Order, 1827

- Grand Cross of the Zähringer Lion, 1827

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 11 April 1830

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 11 April 1830 Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1836

Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1836 Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of Albert the Bear, 12 June 1837

Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of Albert the Bear, 12 June 1837 Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 17 January 1839

Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 17 January 1839 Kingdom of Hanover:

Kingdom of Hanover:

- Knight of St. George, 1840

- Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order

Electorate of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Golden Lion, 4 May 1844

Electorate of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Golden Lion, 4 May 1844

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1847

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1847 Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 31 May 1850

Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 31 May 1850

Family and Children

Nicholas I had seven children with his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna.

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor Alexander II | 29 April 1818 | 13 March 1881 | married 1841, Princess Marie of Hesse; had children |

| Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna | 18 August 1819 | 21 February 1876 | married 1839, Maximilian de Beauharnais, 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg; had children |

| Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna | 11 September 1822 | 30 October 1892 | married 1846, Charles, King of Württemberg; had no children |

| Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna | 24 June 1825 | 10 August 1844 | married 1844, Prince Frederick William of Hesse-Kassel; had one child (who died as a baby) |

| Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich | 21 September 1827 | 25 January 1892 | married 1848, Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg; had children |

| Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich | 8 August 1831 | 25 April 1891 | married 1856, Duchess Alexandra Petrovna of Oldenburg; had children |

| Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich | 25 October 1832 | 18 December 1909 | married 1857, Princess Cecilie of Baden; had children |

Nicholas also had three other children with different mothers.

See also

In Spanish: Nicolás I de Rusia para niños

In Spanish: Nicolás I de Rusia para niños

- History of Russia

- Imperial Russia

- La Russie en 1839

- The Third Section

- Tsars of Russia family tree

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |