Klemens von Metternich facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

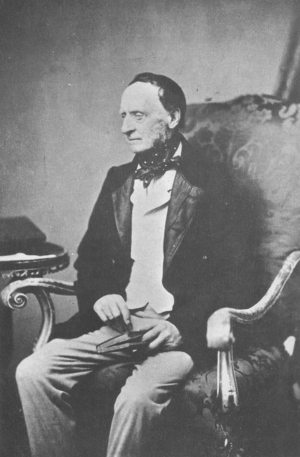

Klemens von Metternich

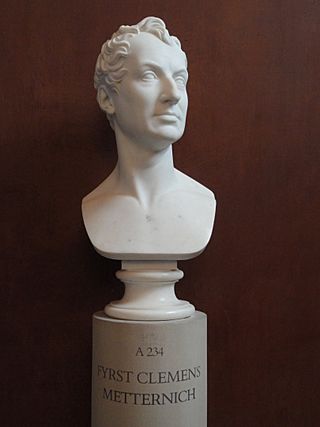

Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Thomas Lawrence, 1815

|

|

| Chancellor of the Austrian Empire | |

| In office 25 May 1821 – 13 March 1848 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Franz Anton as Minister-President |

| Foreign Minister of the Austrian Empire | |

| In office 8 October 1809 – 13 March 1848 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Preceded by | Count Warthausen |

| Succeeded by | Count Charles-Louis de Ficquelmont |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 May 1773 Koblenz, Electorate of Trier, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 11 June 1859 (aged 86) Vienna, Austrian Empire |

| Nationality | German Austrian |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | See list |

| Parents |

|

| Education | University of Strasbourg, University of Mainz |

| Known for | The Congress of Vienna, Minister of State, Conservatism, Concert of Europe |

| Signature |  |

Klemens von Metternich (born May 15, 1773 – died June 11, 1859) was an important Austrian leader and diplomat. He was known for being a conservative, meaning he liked to keep things traditional and avoid big changes.

For about 30 years, Metternich was at the center of European politics. He served as Austria's foreign minister from 1809 and later as Chancellor from 1821. He played a key role in maintaining the "Concert of Europe". This was a system where major European powers worked together to keep peace and balance of power after the Napoleonic Wars. He had to resign in 1848 because of widespread liberal revolutions.

Metternich was born into a noble family in 1773. His father was also a diplomat. Klemens received a good education at universities in Strasbourg and Mainz. He quickly rose through diplomatic ranks. He served as an ambassador in places like Saxony, Prussia, and especially Napoleonic France.

One of his first big jobs as Foreign Minister was to arrange a peace deal with France. This included the marriage of Napoleon to the Austrian princess Marie Louise. Later, he helped bring Austria into the war against Napoleon. He signed the treaty that sent Napoleon into exile. He then led Austria's team at the famous Congress of Vienna. This meeting decided how Europe would be divided after Napoleon's defeat. For his work, he was given the title of Prince in 1813.

Under Metternich's leadership, the "Metternich system" of international meetings continued for another ten years. Austria worked closely with Russia and Prussia. This was a time when Austria was very important in European diplomacy. At home, Metternich was Chancellor from 1821 to 1848. He served under Emperors Francis I and Ferdinand I. After a short time in exile, he returned to Vienna in 1851. He offered advice to the new emperor, Franz Josef. Metternich died in 1859 at the age of 86. He had outlived many of the politicians from his time.

Metternich was a strong conservative. He wanted to keep the balance of power in Europe. He especially tried to stop Russia from expanding too much. He also disliked liberalism (ideas about individual rights and freedoms). He worked hard to prevent the Austrian Empire from breaking apart. For example, he crushed nationalist revolts in Austrian-controlled Italy. At home, he used censorship and a spy network to stop unrest.

People have both praised and criticized Metternich. His supporters say he helped prevent major wars in Europe for many years. They admired his diplomatic skills, especially since Austria was not always the strongest country. His critics, however, say he stopped Austria from making important reforms. They believe he was a barrier to progress. Metternich also loved the arts, especially music. He knew famous composers like Haydn, Beethoven, and Strauss.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Klemens Metternich was born on May 15, 1773. His family was old and noble, from the House of Metternich. His father, Franz Georg Karl, was a diplomat. His mother was Countess Maria Beatrix Aloisia von Kageneck. Klemens was named after Prince Clemens Wenceslaus of Saxony.

At the time, his family owned several estates. These included a castle in Winneberg and land in Königswart, Bohemia. Metternich's father was the Austrian ambassador to several German states. Klemens's mother oversaw his early education. He learned French better than German because of their closeness to France. As a child, he often went on official visits with his father. He also had a tutor who taught him various subjects and skills.

In 1788, Metternich began studying law at the University of Strasbourg. He was described as "happy, handsome and lovable" by his tutor. In 1790, he attended the coronation of Emperor Leopold II in Frankfurt. He had an honorary role in the ceremony. This allowed him to meet important nobles and the future Emperor Francis II.

From 1790 to 1792, Metternich studied law at the University of Mainz. This university offered a more traditional education. During summers, he worked with his father, who was a high-ranking official in the Austrian Netherlands. In 1792, France declared war on Austria. This made it impossible for Metternich to continue his studies in Mainz. He then worked for his father and was sent on a special mission to the war front. He learned a lot about warfare during this time. In 1794, he was sent to England for official business.

Marriage and Early Diplomacy

In England, Metternich met King George III and important British politicians. He also met the famous composer Joseph Haydn. In September 1794, he left England to become a diplomat in the Austrian Netherlands. However, the French army was advancing, and the government there was in retreat. In October, France took over all of Metternich's family estates except Königswart.

Disappointed, Metternich joined his parents in Vienna in November. On September 27, 1795, he married Countess Eleonore von Kaunitz-Rietberg. She was the granddaughter of a former Austrian chancellor. This marriage helped Metternich enter Vienna's high society. One condition of the marriage was that Metternich could not be a diplomat while Eleonore's grandfather was alive. Their daughter Maria was born in January 1797.

After the grandfather's death in 1797, Metternich could finally pursue diplomacy. He attended the Congress of Rastatt as a secretary. He later became a representative for some German states. He stayed at Rastatt until 1799. During this time, his sons Francis and Klemens were born. Sadly, both died young.

Becoming an Ambassador

Dresden and Berlin

After Austria's defeat in the War of the Second Coalition, Metternich was offered several diplomatic jobs. He chose to be ambassador to Dresden in 1801. He wrote a detailed plan for his work, showing his growing understanding of statesmanship. In Dresden, he enjoyed the social life. He also made important friends, including Friedrich Gentz, a writer who became his close adviser.

In 1803, Metternich's family received new lands and the title of Prince. This was to make up for their lost estates. Metternich was then appointed ambassador to Prussia. He arrived at a crucial time in Europe. He became worried about Napoleon Bonaparte's growing power in France. Russia's Tsar Alexander I shared this fear and kept Metternich informed.

By 1805, Austria decided to act against Napoleon. Metternich's job was to convince Prussia to join the alliance. However, Prussia did not join, and the alliance was defeated at the Battle of Austerlitz. Prussia then signed a treaty with France.

Paris

After these events, Metternich became Ambassador to France in 1806. He was happy to be sent to Paris with a good salary. He arrived in August 1806 and met the French foreign minister and Napoleon himself. Metternich's wife and children joined him later. He used his charm to become well-known in Parisian society.

After the Treaties of Tilsit in 1807, Metternich saw that Austria was in a very weak position. But he believed the peace between Russia and France would not last. He pushed for an alliance between Russia and Austria. Over time, Metternich became convinced that war with France was unavoidable.

In August 1808, Metternich had a famous argument with Napoleon about war preparations. Napoleon then prevented Metternich from attending the Congress of Erfurt. Metternich was glad to hear that Napoleon failed to convince Russia to invade Austria. In late 1808, Metternich returned to Vienna to discuss invading France. He reported that France was not fully united behind Napoleon. He also thought Russia would not want to fight Austria.

When Austria declared war on France in 1809, Metternich was arrested in Paris. This was in response to French diplomats being arrested in Vienna. He was later exchanged for the French diplomats and returned to Austria.

Foreign Minister of Austria

Peace with France

Back in Austria, Metternich saw the Austrian army defeated at the Battle of Wagram in 1809. The Foreign Minister, Stadion, resigned. The Emperor offered the job to Metternich. Metternich agreed to become a minister of state first. He led peace talks with the French. He then officially became Foreign Minister on October 8, 1809.

One of Metternich's first tasks was to arrange the marriage of Napoleon to Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria. This marriage was meant to create peace between the two countries. Napoleon agreed, and they were married in March 1810. Metternich then traveled to France. He stayed for six months, working to improve the peace terms for Austria. He won some small concessions, like better trading rights and a delay in war payments. He also got the limit on the Austrian army lifted, which was a sign of more independence for Austria.

As France's Ally

When Metternich returned to Vienna in October 1810, he was less popular. He believed a weak Austria should avoid another French invasion. So, he made an alliance with Napoleon in March 1812. This treaty was more favorable to Austria than Prussia's. It only required 30,000 Austrian troops to fight with France. This allowed Metternich to assure Britain and Russia that Austria still wanted to limit Napoleon's power. He met Napoleon one last time in Dresden in May 1812, before Napoleon invaded Russia.

The Dresden meeting showed that Austria's influence was at its lowest point. Metternich wanted to regain this influence by proposing peace talks led by Austria. Over the next three months, he slowly moved Austria away from France. He avoided alliances with Prussia or Russia. He wanted to find a way to secure a place for the combined Bonaparte-Habsburg dynasty. He worried that if Napoleon was defeated, Russia and Prussia would gain too much power. But Napoleon was stubborn, and the war continued. Austria's alliance with France ended in February 1813. Austria then became neutral.

As a Neutral Power

Metternich was less eager to turn against France than others. He preferred his own plans for a general peace. In November 1813, he offered Napoleon the "Frankfurt proposals". These would let Napoleon remain Emperor but reduce France to its "natural borders". This meant France would lose control of most of Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands. Napoleon delayed, expecting to win the war, and lost this chance. By December, the Allies had taken back the offer.

By early 1814, Allied armies were closing in on Paris. Napoleon finally agreed to the Frankfurt proposals, but it was too late. The Allies now offered harsher terms, which Napoleon rejected. The Allies were not doing well in the war. Metternich worried that Napoleon's retreat would cause chaos. He believed peace had to be made soon. He sent proposals to France and Russia, but they were rejected.

After some battles, a truce was called. Metternich began preparing Austria for war with France. The truce gave Austria time to fully mobilize its army. In June, Metternich went to Gitschin in Bohemia to handle negotiations. He also started a relationship with Princess Wilhelmine, Duchess of Sagan. She had a strong influence on him.

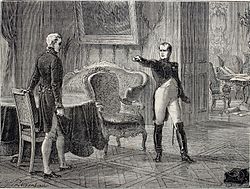

Metternich met with the Tsar and agreed on general peace demands. They set out a plan for Austria to join the war on the Allied side. Metternich then met Napoleon in Dresden. The meeting was difficult but effective. They agreed that peace talks would start in Prague in July. However, Napoleon's representatives did not have enough power to negotiate. This convinced Metternich that Napoleon would not negotiate until France itself was threatened. After an ultimatum from Metternich went unanswered, Austria declared war on August 12.

As a Coalition Partner

Austria's declaration of war was seen by some as a failure of Metternich's diplomacy. But Metternich saw it as part of a larger plan. He worked to keep the Coalition together and limit Russia's power in Europe. He succeeded in getting an Austrian general, Prince of Schwarzenberg, named supreme commander of the Coalition forces. He also made sure the three allied monarchs (Alexander, Francis, and Prussia's Frederick William III) followed their armies.

With the Treaties of Teplitz, Austria remained flexible about the future of France, Italy, and Poland. On October 18, 1813, Metternich saw the successful Battle of Leipzig. Two days later, he was rewarded with the rank of prince. Metternich was happy when Frankfurt was retaken. He was determined to prevent a strong, unified German state. He even offered Napoleon generous terms to keep him as a balance against other powers. Napoleon agreed to talk, but the talks were delayed.

Before talks could begin, Coalition armies crossed the Rhine in December. Metternich went to Basel in January 1814. He had arguments with Tsar Alexander, especially about France's future. However, Metternich and the British diplomat Viscount Castlereagh formed a good working relationship. The talks with France stalled. After some battles, Coalition forces had to retreat. This eased Metternich's fears that Alexander might act alone.

Metternich continued negotiations with the French. By mid-March 1814, the Coalition was on the offensive again. Metternich was tired of trying to hold the Coalition together. The Allies agreed to restore the Bourbon dynasty in France. Francis rejected Napoleon's last plea to abdicate in favor of his son. Paris fell on March 30. Metternich arrived in Paris on April 7. He was annoyed that Tsar Alexander seemed to be in control.

The Austrians disliked the terms of the Treaty of Fontainebleau, which Russia had imposed on Napoleon. But Metternich signed it on April 11. He then focused on protecting Austrian interests in the coming peace. He made sure that the Italian regions of Lombardy and Venetia, lost in 1805, were returned to Austria.

On the division of Poland and Germany, Metternich was limited by the Allies' interests. The issue was postponed until after a peace treaty. Metternich also wanted to give the restored French monarchy the resources to prevent new revolutions. The generous Treaty of Paris was signed on May 30. Metternich then went to England with Tsar Alexander. He enjoyed his four weeks there, restoring his and Austria's reputation. He received an honorary law degree from the University of Oxford. In contrast, Alexander was often rude. Little diplomacy happened, but it was agreed that proper discussions would take place in Vienna. Metternich returned to Austria in mid-July 1814. His return to Vienna was celebrated.

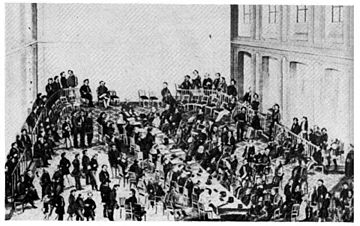

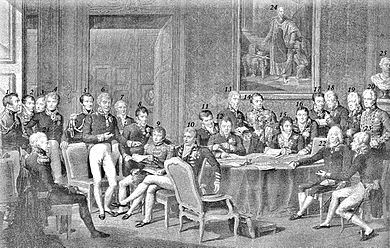

Congress of Vienna

In the autumn of 1814, leaders from many European countries gathered in Vienna. Before the ministers from the "Big Four" (Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia) arrived, Metternich stayed outside the city. He encouraged them to join him there, but they declined. Four meetings were held in Vienna. They decided how the Congress would work. Metternich was pleased that his aide, Friedrich Gentz, was named secretary for the "Big Six" negotiations (the Big Four plus France and Spain).

Other countries were angry that they were excluded from these early decisions. So, the Big Six became the Preliminary Committee of the Eight. They decided to postpone the Congress until November 1. In fact, it was postponed again. Metternich organized many lavish parties and entertainments for the delegates.

Metternich then focused on stopping anti-Austrian feelings in Italy. He also learned that the Duchess of Sagan was spending time with the Tsar. He was disappointed and tired from social events. He made a mistake during talks about Poland, suggesting Austria could match Russia militarily. Despite this, Emperor Francis refused to fire him. A political crisis happened in Vienna in November. The Tsar declared that Russia would not compromise on its claim to Poland. The other countries completely rejected this. It seemed agreement was impossible. During this time, the Tsar even challenged Metternich to a duel. However, the Tsar soon changed his mind and agreed to divide Poland. He also became more flexible about Saxony. For the first time, France was allowed to join all the main discussions.

With this new agreement, the major issues about Poland and Germany were settled in February 1815. Austria gained land in Poland and prevented Prussia from taking Saxony. But Austria had to accept Russia's power in Poland and Prussia's growing influence in Germany. Metternich then worked to get German states to agree to a new Federal Diet. This Diet would help balance Prussia's power. He also worked on other smaller issues, like navigation rights on the Rhine.

The start of Lent on February 8 gave Metternich more time for Congress issues. He also had private talks about southern Italy. There, Joachim Murat was reportedly raising an army. On March 7, Metternich received news that Napoleon had escaped from Elba. Within an hour, he met with the Tsar and the King of Prussia. Metternich wanted to avoid hasty decisions. At first, the news had little impact on the Congress.

Finally, on March 13, the Big Five declared Napoleon an outlaw. The Allies began preparing for renewed fighting. On March 25, they signed a treaty, agreeing to send 150,000 men each. After the military leaders left, the Vienna Congress got serious. They set the borders for an independent Netherlands. They also formalized plans for a loose confederation of Swiss cantons and confirmed earlier agreements about Poland. By late April, only two big issues remained: organizing a new German federation and the problem of Italy.

The Italian issue soon came to a head. Austria had strengthened its control over Lombardy-Venice. On April 18, Metternich announced that Austria was formally at war with Murat's Naples. Austria won a battle on May 3 and captured Naples less than three weeks later. Metternich then delayed a decision on Italy's future until after Vienna. Discussions about Germany continued until early June. A joint Austrian-Prussian plan was approved. It left most constitutional issues to the new German diet. Emperor Francis himself would be its president. Metternich was pleased with the outcome. He could use the diet to his advantage many times. A final treaty was signed on June 19, officially ending the Vienna Congress. Metternich had left on June 13 for the front line, ready for a long war against Napoleon. However, Napoleon was decisively defeated at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18.

Paris and Italy After Vienna

Metternich soon returned to Paris with the Allied leaders. They discussed peace terms again. After 133 days of talks, the second Treaty of Paris was signed on November 20. Metternich was happy with the result. France lost only a small amount of land and had to pay money. It also accepted an army of occupation.

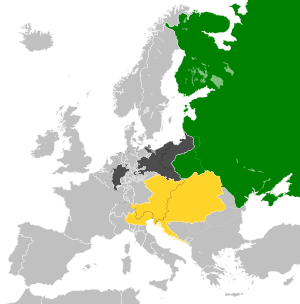

A separate treaty, proposed by Alexander and revised by Metternich, was signed on September 26. This created a new Holy Alliance between Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Metternich didn't really want this treaty because of its vague liberal ideas. Most European states eventually signed it. Soon after, another treaty confirmed the Quadruple Alliance. It also set up the Congress System for regular diplomatic meetings. With Europe at peace, Austria now controlled much more land than when Metternich became Foreign Minister.

Metternich then focused on Italy. He visited the country in December 1815. He tried to convince Emperor Francis to give the region some self-rule, but he failed. Metternich spent four months in Italy. He was very busy and had eye problems. He tried to manage Austrian foreign policy from Milan. He was criticized for being away from Vienna. However, his enemies could not take advantage of his absence. The Empress, who was a critic of Metternich, died in April. Metternich returned to Vienna on May 28, 1816. The rest of 1816 was quiet for him. He was concerned about money and the spread of liberal and nationalist ideas. In November, he was saddened by the death of a close friend. He later wrote that his "life ended there."

In June 1817, Metternich escorted the Emperor's daughter, Maria Leopoldina, to Italy. He traveled around Italy again. He was worried by the lack of reforms there. He again asked for more local control for the regions. When this failed, Metternich decided to work on general administrative reforms for the whole Empire. He returned to Vienna in September 1817. He was immediately busy with his daughter Maria's wedding. He became ill from the stress. After recovering, he submitted his proposals for Italy to Francis. The administration would remain undemocratic, but there would be new ministries with local responsibilities. The divisions would be regional, not national. Francis accepted the revised proposals with some changes.

International Congresses

Metternich's main goal was to keep the major European powers united. He was also worried about Russia's growing influence and its possible takeover of parts of the Ottoman Empire. In April 1818, Britain proposed a Congress at Aachen. Metternich pushed for this meeting. He went to a spa town for his health. There, he learned of his father's death. He visited his family estate and then Frankfurt. He encouraged German states to agree on procedures. He also visited his birthplace, Koblenz, for the first time in 25 years.

At Aachen, Metternich pushed for allied troops to leave France. He also wanted ways to keep the European powers united. The troop withdrawal was agreed quickly. But the agreement to stay united only applied to the Quadruple Alliance. Metternich rejected the Tsar's ideas for a single European army. His own suggestions for stricter controls on freedom of speech were hard for Britain to support openly.

Metternich returned to Vienna in December 1818. He spent time with his children. He monitored Italy and Germany. His trip to Italy was cut short by the murder of a conservative German writer, August von Kotzebue. Metternich decided that if German governments wouldn't act, Austria would force them. He called a meeting in Karlsbad. He met with the King of Prussia beforehand. Metternich succeeded in getting agreement for conservative measures, known as the Carlsbad Decrees. These were criticized by outsiders but pleased Metternich.

At a conference in Vienna later that year, Metternich had to give up his plans to reform the German federation. He regretted forcing its original constitution through so quickly. However, he held his ground on other issues. The Conference's final act was very traditional, just as Metternich wanted. He stayed in Vienna until May 1820. On May 6, his daughter Klementine died from tuberculosis. His eldest daughter Maria also died in July. This led his wife and remaining children to move to France for cleaner air.

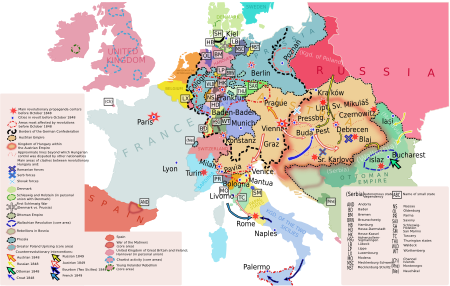

The rest of 1820 was filled with liberal revolts. Metternich was torn between his conservative promises and staying out of countries where Austria had no interest. He chose "sympathetic inactivity" for Spain. But a revolt in Naples in July forced King Ferdinand I to accept a new constitution. Metternich reluctantly agreed to attend the Congress of Troppau in October to discuss this. The Tsar agreed to moderate intervention. Metternich wrote a long memo outlining his conservative ideas, including an attack on the free press.

The Congress ended in December. The next step was a congress at Laibach to discuss intervening in Naples. Metternich controlled Laibach more than any other congress. He oversaw Ferdinand's rejection of the liberal constitution. Austrian armies went to Naples in February and entered the city in March. When similar revolts broke out in Piedmont in March, Metternich had the Tsar nearby. The Tsar agreed to send 90,000 men to show support. Metternich was worried about the cost of his policy. He was relieved when he was made Court Chancellor and Chancellor of State on May 25. This position had been empty since 1794. He was also pleased by the renewed closeness between Austria, Prussia, and Russia.

Chancellor of Austria

Hanover, Verona, and Czernowitz

In 1821, a revolt in the Ottoman Empire threatened its collapse. Metternich wanted a strong Ottoman Empire to balance Russia's power. So, he opposed Greek nationalism. He got the Tsar to agree not to act alone. He also met with British leaders in Hanover in October. They agreed to support Austria's position on the Balkans. Metternich was happy, especially because he met Princess Dorothea von Lieven again.

The Tsar was still undecided. He sent a diplomat to Vienna in February 1822. Metternich convinced the Russian to let him guide events. Austria promised to support Russia if other allies did too. Metternich's opponent at the Russian court, Kapodistrias, retired. However, by April, Russia wanted to intervene in Spain. Metternich thought this was "utter nonsense." He stalled for time. He convinced the British to come to Vienna before a congress in Verona. But the British leader died in August.

Without his British ally, Metternich's position weakened. The Congress of Verona was a big social event but less successful diplomatically. It was supposed to be about Italy but focused on Spain. Austria urged non-intervention. But France pushed for a joint invasion. Prussia and Russia pledged troops. Metternich worried about sending so many troops to Spain. He still pledged moral support for the joint force.

He stayed in Verona until December. He then spent time in Venice with the Tsar and in Munich. He returned to Vienna in January 1823. After Verona, he traveled less because of his new Chancellor role and his health. He was happy when his family arrived from Paris in May. He again became a prominent figure in Viennese society.

Politically, 1823 was disappointing. In March, the French crossed into Spain alone. Metternich also thought the new Pope Leo XII was too pro-French. There were problems between Austria and German states about being excluded from Verona. Also, Metternich's attempts to discredit a Russian diplomat backfired. Worse, in September, Metternich fell ill with a fever while meeting the Emperor and Tsar. He couldn't continue the talks. The Tsar, impatient, asked for a congress in St. Petersburg to discuss the Eastern Question. Metternich, worried about Russia dominating, could only play for time.

The Tsar's proposals for the St. Petersburg meetings were not popular with other European powers. British Foreign Secretary George Canning slowly pulled away. Metternich believed he had gained influence over the Tsar. He also renewed his conservative plans from Karlsbad. He tried to increase Austrian influence over the German Federal Diet. He told the press they could no longer publish meeting minutes, only rulings.

In January 1825, Metternich's wife Eleonore became ill. He reached her in Paris shortly before she died on March 19. He mourned her deeply. He left Paris for the last time in April. He declined the Pope's invitation to become a cardinal. In July, Metternich visited his daughters in Bad Ischl. He received reports about the Greek revolt being crushed. He also dealt with the fallout from St. Petersburg. By mid-May, it was clear the allies couldn't agree. The Holy Alliance was no longer strong.

Hungarian Diets, Alexander I's Death, and Italy

In the early 1820s, Metternich advised Francis to call the Hungarian Diet to approve financial reforms. However, the Diet of 1825-1827 was full of criticism. Hungarian nobles complained that the Empire was taking away their historic rights. Metternich found this annoying. He was alarmed by the growth of Hungarian nationalism.

Back in Vienna in December, he heard of Tsar Alexander's death. He had mixed feelings. He knew the Tsar well and was reminded of his own age. But the death also offered a fresh start in diplomacy. He took credit for predicting the Decembrist liberal revolt that the new Tsar Nicholas I had to crush. Metternich sent Archduke Ferdinand to meet Nicholas first. Metternich also befriended the British envoy, the Duke of Wellington, to help charm Nicholas.

Despite this, the first 18 months of Nicholas's reign were not good for Metternich. Britain, not Austria, oversaw Russian-Ottoman talks. Metternich had no influence over the resulting treaty. France also began to move away from Metternich's non-intervention policy. In August 1826, the Russian Foreign Minister rejected Metternich's idea for a congress to discuss events in Portugal. Metternich accepted this with "surprising resilience." On March 29, 1827, Metternich attended the funeral of Beethoven.

On November 5, 1827, Metternich married Baroness Antoinette von Leykam. She was only twenty. Their marriage caused some criticism because of their different social status. But Antoinette's charm soon won over Viennese society. The same day, British, Russian, and French forces destroyed the Ottoman fleet. Metternich worried that more intervention would destroy the Ottoman Empire. This would upset the balance of power. To his relief, the new British Prime Minister, Wellington, also feared Russia gaining too much power.

After his proposals for congresses were rejected again, Metternich stepped back from the Eastern Question. He watched as a treaty was signed in September 1829. He publicly criticized it for being too harsh on Turkey. But privately, he was satisfied with its leniency. He liked the promise of Greek self-rule, making it a buffer against Russian expansion.

Metternich's personal life was full of sadness. In November 1828, his mother died. In January 1829, Antoinette died, five days after giving birth to their son, Richard von Metternich. His son Viktor died in November 1829 from tuberculosis. Metternich spent Christmas alone and depressed. He was worried by the harsh methods of some conservatives and the return of liberalism.

In May, Metternich took a holiday at his estate in Johannisberg. He returned to Vienna a month later, still worried by "chaos in London and Paris." He met with the Russian Foreign Minister in July. They agreed that panic was not needed unless the new French government showed territorial ambitions. Metternich was pleased by this. But his mood was soured by news of unrest in Brussels and calls for new constitutions in Germany. He wrote that it was the "beginning of the end" of Old Europe. However, he was encouraged that the French Revolution had made a Franco-Russian alliance impossible. He was also happy that the Netherlands called for an old-style congress. The Hungarian Diet in 1830 was more successful. Archduke Ferdinand was crowned King of Hungary with little disagreement. In November, Metternich became engaged to 25-year-old Countess Melanie Zichy-Ferraris. They married on January 30, 1831.

In February 1831, rebels took cities in Italy and asked France for help. Their former rulers asked Austria for help. Metternich was careful not to send Austrian troops into the Papal States without the Pope's permission. But he occupied Parma and Modena. He eventually entered Papal territory. Italy was peaceful by the end of March. He withdrew troops in July, but they returned in January 1832 to stop another rebellion.

By now, Metternich was visibly aging. His hair was gray, and his face was drawn. In February 1832, his daughter Melanie was born. In 1833, a son, Klemens, was born but died at two months old. In October 1834, another son, Paul, was born. In 1837, his third child with Melanie, Lothar, was born. Politically, Metternich had a new opponent, Lord Palmerston, who became British Foreign Secretary in 1830. By the end of 1832, they disagreed on almost every issue. Metternich was annoyed by Palmerston's insistence that Britain could oppose Austria's stricter university controls in Germany. Metternich also worried that if future congresses were held in Britain, his own influence would decrease.

Eastern Question and Peace

In 1831, Egypt invaded the Ottoman Empire. Metternich feared the Empire's collapse. He proposed international support for the Ottomans and a congress in Vienna. But France was hesitant, and Britain refused a Vienna congress. By summer 1833, Anglo-Austrian relations were very bad. Metternich was more confident with Russia. However, he was wrong. He watched Russia intervene in the region from afar.

He met the King of Prussia and accompanied Francis to meet Tsar Nicholas in September 1833. The meeting with Prussia went well. Metternich still felt he could control the Prussians. The meeting with Nicholas was more difficult. But they reached three agreements that formed a new conservative alliance. This alliance aimed to uphold the existing order in Turkey, Poland, and elsewhere. Metternich was happy, though he had to agree to be tougher on Polish nationalists.

Soon after, he heard about the Quadruple Alliance of 1834 between Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal. This alliance of liberal countries was a challenge to Austria's values. Metternich tried to remove the British Foreign Secretary and build agreements between different power blocs. Palmerston did leave office temporarily, but not because of Metternich. Large-scale war was avoided, and the Quadruple Alliance began to fall apart.

On March 2, 1835, Emperor Francis died. His epileptic son, Ferdinand I, succeeded him. Metternich valued legitimacy and worked to keep the government running. He accompanied Ferdinand to his first meeting with Tsar Nicholas and the King of Prussia. Ferdinand was overwhelmed. The next few years were relatively peaceful for Metternich. Diplomatic incidents were limited to arguments with Palmerston. Metternich also worked to bring new technology, like railways, to Austria.

The most pressing issue was Hungary. Metternich was slow to support the nationalist leader Lajos Kossuth. His hesitation showed his declining political power. At court, Metternich lost influence to Franz Anton von Kolowrat-Liebsteinsky. This was especially true for military budgets. After failing to force constitutional reform in 1836, Metternich had to share power with Kolowrat and Archduke Ludwig. Decision-making became very slow. Managing his large estates was also a financial strain, especially with four young children.

Metternich had long predicted a new crisis in the East. When the Second Turko-Egyptian War broke out in 1839, he wanted to re-establish Austria's diplomatic importance. He quickly gathered representatives in Vienna. They issued a statement pledging support to Constantinople. However, Tsar Nicholas challenged Vienna's central role. Metternich worked so hard that he fell ill. He spent five weeks resting.

Austria lost the initiative. Metternich had to accept that London would be the new center for Eastern Question talks. His idea for a European League of Great Powers became unimportant. His proposals for a congress in Germany were also ignored. An attempt to strengthen the influence of ambassadors in Vienna was also rejected. This set the tone for the rest of Metternich's time as Chancellor. His illness seemed to have broken his love for the job. Over the next decade, his wife quietly prepared for his retirement or death.

Metternich's work in the early 1840s focused on Hungary and national identity within the Austrian Empire. His ideas for Hungary came too late. Kossuth had already led a strong Hungarian nationalist movement. Metternich's support for other nationalities was inconsistent. He only opposed those that threatened the Empire's unity.

At the Conference of State, Metternich lost a key ally in 1840. This led to more paralysis in the Austrian government. Metternich struggled to enforce even the censorship he wanted. There were no major external threats to the regime. Italy was quiet. Tsar Nicholas, however, had a low opinion of Austria. After a trip to Italy in 1845, the Tsar unexpectedly stopped in Vienna. He was a difficult guest. But he reassured Metternich that Russia would not invade the Ottoman Empire again.

Two months later, Austria and Russia had to work together over the Galician slaughter and a declaration of independence from Kraków. Metternich authorized the occupation of Kraków. He wanted to end its special independence granted in 1815. After months of talks, Austria annexed the city in November 1846. Metternich saw it as a personal victory. But it was controversial. Polish dissidents were now officially part of Austria. The Europe-wide Polish movement actively worked against the "Metternich system." Britain and France were outraged. Calls for Metternich's resignation were ignored. For the next two years, Ferdinand could not step down. Metternich believed Austria needed him to hold the government together.

Revolution of 1848

Even though Metternich was getting tired, he kept writing memos. But he did not see the coming crisis. The new Pope Pius IX was seen as a liberal nationalist, which challenged Metternich. At the same time, Austria faced unemployment and rising prices due to bad harvests. Metternich was surprised by the outcry when he ordered the occupation of Ferrara in 1847.

France and Austria were forced to support breakaway groups in the Swiss Civil War. They proposed a conference, but the government crushed the revolt. This was a blow to Metternich's reputation. His opponents in Vienna called it proof of his incompetence. In January 1848, Metternich predicted trouble in Italy. He sent an envoy and planned for an Italian chancellery. In late February, Austrian general Joseph Radetsky put Austrian Italy under martial law as unrest spread. Despite this and news of a new revolution in France, Metternich was cautious. He still thought a revolution in Austria was unlikely. A diplomat described him as "having shrunk to a shadow of his former self."

On March 3, Kossuth gave a powerful speech in the Hungarian Diet, demanding a constitution. It wasn't until March 10 that Metternich seemed worried about events in Vienna. There were threats and counter-threats. Two petitions called for more freedom and representation. Students held demonstrations. On March 13, they cheered the imperial family but shouted angrily at Metternich.

Metternich was called to a meeting. He sent troops into the streets and announced a small concession. In the afternoon, the crowd became hostile. Troops opened fire, killing five people. The mob became truly angry. Students offered to form a pro-government group if their demands were met. Archduke Ludwig wanted to accept and told Metternich he must resign. Metternich reluctantly agreed.

After sleeping in the Chancellery, he was advised to either take back his resignation or leave the city. Ludwig sent him a message saying the government couldn't guarantee his safety. Metternich left for a friend's house. With help from friends, he reached Prince Liechtenstein's family home. Metternich's daughter Leontine joined them. She suggested England as a safe place. Metternich, Melanie, and his son Richard set out for England. Metternich's resignation was met with cheers in Vienna. Even common people welcomed the end of his conservative era.

Exile, Return, and Death

After a difficult nine-day journey, Metternich, his wife, and son Richard arrived in Arnhem, Netherlands. They stayed there until Metternich felt stronger. They then went to Amsterdam and The Hague. On April 20, they landed in London. They stayed in a hotel before finding a permanent home. Metternich mostly enjoyed his time in London. The Duke of Wellington tried to keep him entertained. He also had visits from other politicians. The only disappointment was that Queen Victoria did not acknowledge him.

The family rented a house in Eaton Square. His younger children joined them in the summer. He followed events in Austria from afar. He famously said he had never made a mistake. He believed the chaos in Europe proved his policies were right. In Vienna, the press attacked him. They accused him of embezzlement and taking bribes. An investigation cleared him of the serious charges. Searches for evidence of lesser charges found nothing. Metternich's large expense claims were likely normal for diplomacy at the time. He was denied his pension and had to rely on loans.

In mid-September, the family moved to Brighton on the south coast of England. Life there was peaceful, unlike revolutionary Europe. Politicians, including Benjamin Disraeli, visited them. His former friend Dorothea Lieven also visited. Metternich was showing his age and often fainted. He was depressed by the lack of communication from the new Emperor Franz Joseph I. His daughter Leontine wrote to Vienna to encourage contact. In August, Metternich received a warm letter from Franz Joseph, which cheered him up.

In mid-August, Melanie pushed for a move to Brussels. It was cheaper and closer to European affairs. They arrived in October. Their stay lasted over 18 months. Metternich waited for a chance to return to Austrian politics. It was a pleasant and cheap stay. They had visits from politicians, writers, musicians, and scientists. But Metternich grew more bored and homesick. In March 1851, Melanie convinced him to write to the new political leader in Vienna, Prince Schwarzenberg. He asked if he could return if he promised not to interfere in public affairs. In April, he received a positive reply from Franz Joseph.

In May 1851, Metternich left for his Johannisberg estate. He had not visited it since 1845. That summer, he enjoyed the company of the Prussian representative Otto von Bismarck. He also enjoyed a visit from King Frederick William. In September, Metternich returned to Vienna. He was re-energized. Franz Josef asked for his advice on many issues. Both political groups in Vienna tried to win Metternich's favor. Even Tsar Nicholas visited him. Metternich did not like the new Foreign Minister, Karl Ferdinand von Buol. But he thought him incompetent enough to be influenced. Metternich's advice was sometimes very insightful.

Now deaf, Metternich wrote constantly, especially for Franz Josef. He wanted Austria to be neutral in the Crimean War, but Buol disagreed. Metternich's health slowly failed. He became less central after his wife Melanie died in January 1854. In early 1856, he had a brief burst of energy. He arranged a marriage for his son Richard and traveled more. The King of the Belgians and Bismarck visited him. In August 1857, he hosted the future Edward VII of the United Kingdom. Buol grew more resentful of Metternich's advice, especially about Italy. In April 1859, Franz Josef asked him about Italy. According to Metternich's granddaughter Pauline, Metternich begged him not to send an ultimatum to Italy. But Franz Josef said it had already been sent.

Austria began the Second Italian War of Independence against France and Piedmont-Sardinia. This was a disappointment for Metternich and an embarrassment for Franz Josef. Metternich helped replace Buol with his friend Rechberg. But he was too old to be involved in the war itself. Even a special task from Franz Josef in June 1859 was too much for him.

Klemens von Metternich died in Vienna on June 11, 1859, at age 86. He was the last great figure of his generation. Almost everyone important in Vienna came to pay tribute. In the foreign press, his death went almost unnoticed.

Historians' Assessment

Historians generally agree that Metternich was a skilled diplomat. They also agree on his strong commitment to conservatism.

During the 1800s, Metternich was heavily criticized. People said he stopped Austria and Central Europe from becoming more liberal and democratic. They argued that if Metternich hadn't stood in the way, Austria might have reformed. It might have dealt better with its different nationalities. Some even suggest the First World War might not have happened. Instead, Metternich chose to fight against liberalism and nationalism. He used strict censorship and a large spy network. He opposed voting reforms, like Britain's 1832 Reform Bill. Critics say he was stuck in a battle against the "mood of his age."

However, in the 1900s, some historians began to praise Metternich's diplomacy. They saw his policies as reasonable attempts to achieve his goals. His main goal was to keep a balance of power in Europe. Supporters point out that Metternich correctly predicted Russia's desire for dominance. He worked to prevent it, succeeding where others failed later. These historians argue that Metternich promoted legality, cooperation, and dialogue. This helped ensure 30 years of peace, known as the "Age of Metternich." Some authors also give Metternich credit for having some liberal ideals, even if they weren't his main focus.

Critics say Metternich had the power to shape Europe for the better but chose not to. More recent critics, like A. J. P. Taylor, question how much influence Metternich actually had. Robin Okey, a critic, noted that Metternich "had only his own persuasiveness to rely on." This power decreased over time. By this view, his job was to hide Austria's true weakness. Taylor described him as "the most boring man in European history." Critics argue his failures were not just in foreign affairs. At home, he was also powerless, failing to make his own reforms happen.

In contrast, those who defend Metternich call him an "unquestionably master of diplomacy." They say he perfected and shaped diplomacy in his era. Alan Sked argues that Metternich's "smokescreen" might have helped further his principles.

Issue

Metternich had several children:

- With Countess Maria Eleonore von Kaunitz-Rietberg:

- Maria Leopoldina (1797–1820)

- Franz Karl Johann Georg (1798–1799)

- Klemens Eduard (1799)

- Franz Karl Viktor Ernst Lothar Clemens Joseph Anton Adam (1803–1829)

- Klementine Marie Octavie (1804–1820)

- Leontine Adelheid Maria Pauline (1811–1861)

- Hermine Gabriele (Henrietta) Marie Eleonore Leopoldine (1815–1890)

- With Baroness Maria Antoinette von Leykam:

- Richard Klemens Josef Lothar Hermann, 2nd Prince Metternich (1829–1895)

- With Countess Melania Maria Antonia Zichy-Ferraris de Zich et Vásonykeö:

- Melanie Marie Pauline Alexandrine (1832–1919)

- Klemens (1833)

- Paul Klemens Lothar, 3rd Prince Metternich (1834–1906)

- Maria Emilia Stephanie (1836)

- Lothar Stephan August Klemens Maria (1837–1904)

Honours and Arms

Honours

Austrian Empire:

Austrian Empire:

- Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, in Diamonds, 1805

- Knight of the Golden Fleece, 1805

- Golden Civil Cross "For Merit" (1813/1814)

- Chancellor of the Military Order of Maria Theresa

Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1813

Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1813 Kingdom of France:

Kingdom of France:

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, 1814

- Knight of the Holy Spirit, 30 May 1825

- Knight of St. Michael

Russian Empire:

Russian Empire:

- Knight of St. Andrew, 27 August 1813

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky, 27 August 1813

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class, 27 August 1813

Kingdom of Prussia:

Kingdom of Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 13 September 1813

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle, 13 September 1813

- Pour le Mérite (civil), 31 May 1842

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 12 April 1814

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, 12 April 1814 Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 7 December 1814

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 7 December 1814 Kingdom of Sardinia: Knight of the Annunciation, 4 January 1815

Kingdom of Sardinia: Knight of the Annunciation, 4 January 1815 Baden: Grand Cross of the House Order of Fidelity, in Diamonds, 1815

Baden: Grand Cross of the House Order of Fidelity, in Diamonds, 1815 Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1815

Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1815 Kingdom of Hanover:

Kingdom of Hanover:

- Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order, 1816

- Knight of St. George, 1841

Duchy of Parma: Senator Grand Cross of the Constantinian Order of St. George, 1816

Duchy of Parma: Senator Grand Cross of the Constantinian Order of St. George, 1816 Two Sicilies:

Two Sicilies:

- Knight of St. Januarius, 1816

- Grand Cross of St. Ferdinand and Merit, 1816

- Duke of Portella, 1818

Electorate of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Golden Lion, 25 May 1817

Electorate of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Golden Lion, 25 May 1817 Spain:

Spain:

- Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, with Collar, 20 October 1817

- Grandee of the 1st Class, 1824

Württemberg: Knight of the Golden Eagle, 1818

Württemberg: Knight of the Golden Eagle, 1818 Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 5 February 1820

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 5 February 1820 Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 20 June 1820

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 20 June 1820

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, August 1835

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, August 1835 Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of the Order of Albert the Bear, March 1837

Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of the Order of Albert the Bear, March 1837 Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold Empire of Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross

Empire of Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross Brunswick: Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion

Brunswick: Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer

Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class

Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class Holy See: Grand Cross of St. Gregory the Great

Holy See: Grand Cross of St. Gregory the Great Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion

Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion Kingdom of Portugal:

Kingdom of Portugal:

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Christ

- Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword

Grand Duchy of Tuscany: Grand Cross of St. Joseph

Grand Duchy of Tuscany: Grand Cross of St. Joseph

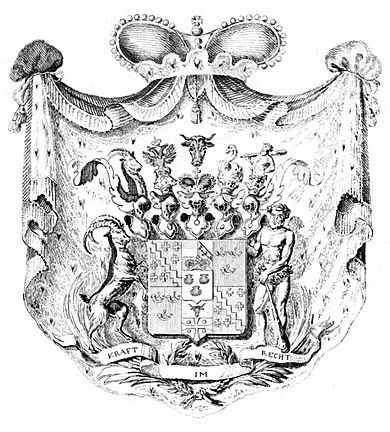

Arms

Other Honours

In 1823, a botanist named J.C. Mikan named a genus of flowering plants from Brazil Metternichia in his honor. These plants belong to the family Solanaceae.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Klemens von Metternich para niños

In Spanish: Klemens von Metternich para niños

- Metternich Stela

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |