Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Duke of Wellington

|

|

|---|---|

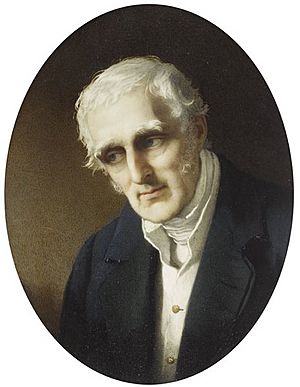

Portrait by Thomas Lawrence, c. 1815-16

|

|

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 17 November 1834 – 9 December 1834 |

|

| Monarch | William IV |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Succeeded by | Sir Robert Peel |

| In office 22 January 1828 – 16 November 1830 |

|

| Monarch | George IV William IV |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Goderich |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Grey |

| Commander-in-Chief of the British Army | |

| In office 15 August 1842 – 14 September 1852 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Hill |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Hardinge |

| In office 22 January 1827 – 22 January 1828 |

|

| Monarch | George IV |

| Preceded by | The Duke of York and Albany |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Hill |

| Leader of the House of Lords | |

| In office 3 September 1841 – 27 June 1846 |

|

| Prime Minister | Sir Robert Peel |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Lansdowne |

| In office 14 November 1834 – 18 April 1835 |

|

| Prime Minister | Sir Robert Peel |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Melbourne |

| In office 22 January 1828 – 22 November 1830 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Goderich |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Grey |

| Additional positions | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Arthur Wesley

1 May 1769 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 14 September 1852 (aged 83) Walmer, England |

| Resting place | St Paul's Cathedral |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Awards |

List

|

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1787–1852 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Battles/wars | |

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS (born 1 May 1769 – died 14 September 1852) was a famous soldier and politician from Britain. He was one of the most important people in Britain during the 1800s. He even served as Prime Minister twice!

Wellington is best known for helping to end the Napoleonic Wars. He led the armies that defeated Napoleon at the famous Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Arthur Wellesley was born in Dublin, Ireland. He joined the British Army in 1787 as a young officer called an ensign. He served in Ireland and later in India. By 1796, he was a colonel and fought in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War. He won a big victory in India at the Battle of Assaye in 1803.

Wellesley became a very important general during the Peninsular War in Europe. He led his forces to victory against the French at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813. After Napoleon was sent away in 1814, Wellesley became an ambassador and was given the title of Duke. When Napoleon returned in 1815, Wellington commanded the army that defeated him at Waterloo. He fought in about 60 battles during his military career.

Wellington was known for his smart defensive fighting style. He often won battles against larger armies while keeping his own losses low. His tactics are still studied in military schools today. After his military career, he became a politician. He was Prime Minister from 1828 to 1830 and again for a short time in 1834. He helped pass a law that gave more rights to Roman Catholics. He remained an important figure in the government until he retired. He was also the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army until he died.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Family Background

Arthur Wellesley came from an important Anglo-Irish family in Ireland. His father was Garret Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington, a talented musician and politician. His mother was Anne Hill-Trevor. Arthur was named after his mother's father.

He was one of nine children. His older brother, Richard, became a very important figure in India.

Birth and Childhood

The exact date and place of Arthur's birth are not fully known, but most people agree he was born on 1 May 1769, in Dublin. He spent his childhood at his family's homes in Dublin and at Dangan Castle in County Meath, Ireland.

Arthur went to several schools, including Eton College from 1781 to 1784. He didn't enjoy his time at Eton. After his father died in 1781, his family had less money. In 1785, Arthur and his mother moved to Brussels. At first, Arthur didn't show much promise, and his mother worried about his future.

In 1786, he went to a French riding academy in Angers. There, he became a skilled horseman and learned French, which was very useful later in his life.

Early Military Career

Joining the Army

Even after his improvements, Arthur needed a job. His family helped him join the army. On 7 March 1787, he became an ensign in the 73rd Regiment of Foot. Soon after, he became an aide-de-camp (a personal assistant) to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. His duties in Dublin were mostly social, like attending parties.

He also became a Member of Parliament (MP) for Trim in the Irish Parliament. He continued to serve in the army, becoming a captain in 1791.

In 1793, he wanted to marry Kitty Pakenham. However, her brother said no because Arthur was young, in debt, and didn't have good prospects. This made Arthur very upset, and he decided to focus seriously on his military career. He bought a higher rank, becoming a major and then a lieutenant colonel in the 33rd Regiment.

Fighting in the Netherlands

In 1794, Wellesley and his 33rd Regiment went to Flanders (part of modern-day Belgium) to fight the French. This was his first experience in battle. The campaign was difficult, and the British army had to retreat. Wellesley learned a lot from this, especially about what not to do in battle. He saw how important good leadership and organization were.

After returning to England, he was promoted to full colonel in 1796. A few weeks later, his regiment was sent to India.

Service in India

Wellesley arrived in Calcutta, India, in 1797. He later went on a short trip to the Philippines. He made sure his soldiers followed strict hygiene rules to stay healthy in the new climate. In 1798, he changed the spelling of his last name to "Wellesley." His older brother, Richard, became the new Governor-General of India.

Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

In 1798, the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War began against Tipu Sultan of Mysore. Wellesley's brother ordered an army to capture Seringapatam, Tipu's capital. Wellesley, now a major-general, was given an important command. He was also an advisor to the army of the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Wellesley's careful planning for supplies and logistics became one of his strengths. His troops marched through jungles from Madras to Mysore. At the Battle of Mallavelly, Wellesley led his men in a successful attack, forcing Tipu's army to retreat.

Siege of Seringapatam

The Battle of Seringapatam began on 5 April 1799. Wellesley led a night attack that failed, causing him to learn an important lesson: never attack an enemy without scouting their positions in daylight first.

After heavy bombing, the British captured the fortress. Wellesley helped secure the area and found Tipu Sultan dead. He was very strict about discipline, punishing soldiers who looted the city to restore order.

After the war, Wellesley, at 30 years old, became the Governor of Seringapatam and Mysore. He worked to improve the tax and justice systems.

Dhoondiah Waugh Insurgency

In 1800, Wellesley was tasked with stopping an uprising led by Dhoondiah Waugh, a former soldier who had become a powerful bandit. Waugh was raiding villages and gathering a large force.

Wellesley led an army of 8,000 soldiers against Waugh's forces, which were much larger but mostly made up of less organized cavalry. Wellesley's troops captured forts and drove Waugh's forces back. On 10 September, at the Battle of Conaghul, Wellesley personally led a charge of 1,400 cavalry against Waugh's remaining 5,000 cavalry. Waugh was killed, ending the uprising. Wellesley even paid for the future care of Waugh's orphaned son.

Second Anglo-Maratha War

In 1802, Wellesley was promoted to major-general. In 1803, he was sent to command an army in the Second Anglo-Maratha War. He decided to attack quickly rather than fight a long defensive war. His army of 24,000 men attacked a Maratha fort, which surrendered on 12 August.

Assaye and Other Victories

On 23 September, Wellesley decided to attack the main Maratha army at the Battle of Assaye, even though they had more soldiers. He led his forces across a river and attacked. Wellesley himself was in the thick of the fighting, with two horses shot from under him. His leadership helped his army win a decisive victory.

The battle was costly for both sides, but the Marathas were defeated. Wellesley later said that Assaye was the best battle he ever fought, even better than Waterloo.

He continued to win battles, including at Argaum and Gawilghur. These victories, along with others by British forces, forced the Marathas to sign a peace treaty.

Wellesley's time in India taught him a lot about military strategy. He learned about discipline, diplomacy, and the importance of good supply lines and intelligence. He also developed his distinctive style of dress.

Leaving India

Wellesley felt he had served long enough in India. In 1804, he asked to return home. He was made a Knight of the Bath for his service. He had also earned a large amount of money from his campaigns. In 1805, he returned to England with his brother.

Return to Britain

Meeting Horatio Nelson

In September 1805, Wellesley, who was not yet famous, met Horatio Nelson, a well-known naval hero. At first, Nelson seemed a bit boastful. But after learning who Wellesley was, Nelson changed his tone and had a very interesting conversation with him about the war. This was the only time the two great military leaders ever met. Nelson died seven weeks later at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Wellesley then served in a short military expedition to Germany. He also became a Tory Member of Parliament in 1806 and later served as Chief Secretary for Ireland.

War Against Denmark

In 1807, Wellesley joined a British expedition to Denmark-Norway. He commanded an infantry brigade in the Second Battle of Copenhagen in August. He fought at Battle of Køge, where his men captured many prisoners.

By 1808, he was a lieutenant general. He was then given command of an expedition to Portugal to fight against the French in the Peninsular War.

Peninsular War

Early Victories in Portugal

Wellesley arrived in Lisbon, Portugal, in April 1809. He quickly went on the attack. He defeated the French at the Second Battle of Porto, crossing the Douro river by surprise.

With Portugal secure, Wellesley moved into Spain to join forces with a Spanish general. At the Battle of Talavera in July 1809, Wellesley's forces fought off several French attacks. However, the British suffered heavy losses. Due to a lack of supplies and the threat of more French troops, Wellesley decided to retreat back into Portugal.

After his victory at Talavera, Wellesley was given the title of Viscount Wellington in August 1809.

Defending Portugal

In 1810, a large French army invaded Portugal. Many people thought the British should leave Portugal. But Wellington had secretly built huge defensive walls and forts, known as the Lines of Torres Vedras, around Lisbon. These defenses, protected by the British navy, stopped the French. The French army, unable to break through and running out of food, had to retreat after six months.

In 1811, Wellington fought the French again at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro. He was promoted to full general for his service. The French still held two important Spanish fortresses, Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz.

Capturing Fortresses and Liberating Madrid

In 1812, Wellington quickly captured Ciudad Rodrigo. He then moved south and captured Badajoz after a month-long siege. The attack on Badajoz was very costly, and Wellington was deeply saddened by the sight of the many British soldiers who died.

His army, now made up of experienced British and Portuguese troops, continued to fight in Spain. He won a major victory at the Battle of Salamanca, which freed the Spanish capital of Madrid. For these successes, he was made Earl of Wellington and later Marquess of Wellington.

Wellington tried to capture the fortress of Burgos, but he failed because he didn't have enough siege cannons. This forced him to retreat. The French armies then combined, outnumbering the British. Wellington withdrew his army back to Portugal.

Driving the French Out of Spain

In 1813, Wellington launched a new attack. He moved through the mountains, surprising the French and forcing them to abandon Madrid. He then caught up with and completely defeated the French army at the Battle of Vitoria. For this victory, he was promoted to field marshal.

After Vitoria, his troops stopped to loot the abandoned French wagons instead of chasing the enemy. Wellington was furious, calling his soldiers "the scum of the earth." However, he later praised them, saying it was amazing what they had become.

He then besieged San Sebastián, which eventually fell. Wellington then pushed the French army back into France, winning battles at the Pyrenees, Bidassoa, and Nivelle. He invaded southern France, winning more battles. His final battle against the French general Soult was at Toulouse. Soon after, news arrived that Napoleon had been defeated and had given up his power.

Wellington was celebrated as a hero in Britain. On 3 May 1814, he was given the highest title: Duke of Wellington. He also received honors from Spain. His popularity grew because of his military wins and his distinctive style.

He then became the British Ambassador to France and later represented Britain at the Congress of Vienna, a meeting of European leaders to reshape Europe after Napoleon's defeat.

The Hundred Days

Facing Napoleon Again

On 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from his exile on the island of Elba and returned to France. He quickly regained control of the country. European countries formed a new alliance against him. Wellington left Vienna to command the British, German, and Dutch armies in what became known as the Waterloo Campaign. These forces were stationed alongside the Prussian army led by Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

Napoleon's plan was to attack the Allied and Prussian armies separately and defeat them before they could join forces.

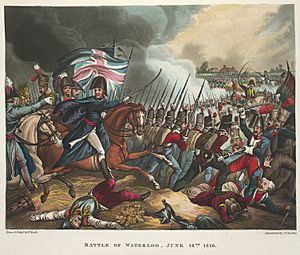

On 18 June 1815, the Battle of Waterloo was fought. This was the first time Wellington and Napoleon faced each other directly. Wellington commanded an army of about 73,000 troops.

The Battle of Waterloo

The battle began with a French attack on a farmhouse called Hougoumont. Then, a large French infantry attack was launched. The French cavalry also charged the British infantry squares many times. Wellington's soldiers formed squares, which were very strong against cavalry charges.

Later in the day, the Prussian army arrived, helping to push back the French. Napoleon then sent his elite Imperial Guard to attack Wellington's center. This was a critical moment.

The British Foot Guards, hidden from view, rose and fired devastating volleys at the advancing French Guard. Other British regiments also attacked. The Imperial Guard, facing heavy fire and outnumbered, began to break and retreat.

News spread through the French lines: "The Guard is retreating! Every man for himself!" Wellington then stood up in his stirrups and waved his hat, signaling a general advance of the Allied line. The French army collapsed and fled in disorder. Wellington and Blücher met, and the Prussians chased the retreating French. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris in November 1815.

Political Career

Becoming Prime Minister

After his military career, Wellington returned to politics. He became the Master-General of the Ordnance in 1818. He was also appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in 1827.

In 1828, Wellington resigned as Commander-in-Chief and became Prime Minister. At first, he didn't live at 10 Downing Street, the official residence, because he found it too small.

Important Reforms

One of the most important things during his time as Prime Minister was the Roman Catholic Emancipation. This law gave Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom most of their civil rights back. This change was pushed by Daniel O'Connell, an Irish Catholic who was elected to Parliament even though he wasn't legally allowed to sit there.

Wellington, who was born in Ireland, understood the issues faced by Catholics. He spoke strongly in favor of the law in the House of Lords. Many members of his own party voted against it, but with help from other parties, the Catholic Relief Act 1829 was passed. Wellington even threatened to resign if the King didn't approve the law.

Because of this, some people were very angry with Wellington. One person even accused him of trying to harm the country. Wellington challenged him to a duel. On 21 March 1829, they met, and Wellington fired his pistol wide, showing he didn't intend to kill. The other person fired into the air, and they made up.

The nickname "Iron Duke" came from this time. It referred to his strong will and determination, especially when he faced unpopularity.

Losing Power and Later Role

Wellington's government fell in 1830. He was against expanding voting rights and political reform. This led to him losing a vote of no confidence.

The next government tried to pass the Reform Bill, which would give more people the right to vote. Wellington and his party tried to stop it. There were protests and riots across the country. Wellington's home, Apsley House, was even attacked by angry crowds. Iron shutters were installed to protect his windows.

Eventually, the Reform Bill passed. Wellington never fully accepted this change.

Wellington gradually became less of a leader in his party, with Robert Peel taking over. When his party returned to power in 1834, Wellington served as foreign secretary and later as a minister without a specific department. He was also re-appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in 1842.

Wellington led his party in the House of Lords from 1828 to 1846. He was a smart politician who worked to make the House of Lords an active part of the government.

Later Life and Death

Family Life

Wellesley married Kitty Pakenham in 1806. They had two sons: Arthur (born 1807) and Charles (born 1808). Their marriage was not very happy, and they often lived apart. Kitty spent most of her time at their country home, Stratfield Saye House, while Wellington was at their London home, Apsley House.

Kitty died of cancer in 1831. Despite their difficult relationship, Wellington was very sad about her death. He found comfort in his close friendship with Harriet Arbuthnot, who was also a widow. They spent their later years together.

Retirement and Final Years

Wellington retired from political life in 1846. However, he remained Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. In 1848, he helped organize military forces to protect London during a time of unrest in Europe.

Wellington died at Walmer Castle in Kent on 14 September 1852, at the age of 83. He died from the effects of a stroke.

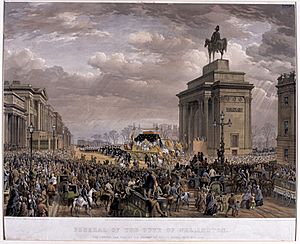

His body was taken by train to London for a state funeral. This is a very rare honor given to only a few important British people. The funeral took place on 18 November 1852. Before the funeral, his body lay in state at the Royal Hospital Chelsea, and many people, including Queen Victoria, came to pay their respects.

He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral in London. His funeral was attended by so many people that there was hardly any space to stand. A large bronze memorial was later created for him in the cathedral.

After his death, newspapers in Ireland and England debated whether he was Irish or English. In 2002, he was ranked 15th in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Personality and Habits

Wellington was known for waking up very early. He didn't like to lie in bed, even when not on campaign. He often slept in a simple camp bed, showing he didn't care much for fancy comforts. He rarely ate between breakfast and dinner.

He was a very practical man and spoke directly. He was known for his stern look and strict discipline. However, he also cared deeply for his soldiers. He would not chase a defeated enemy if it meant too many losses for his own army. The only time he was seen crying in public was after the costly attack on Badajoz, when he saw the many British soldiers who had died. After Waterloo, he also cried when he was given the list of fallen British soldiers.

Wellington became deaf in one ear after an operation in 1822. He was known for his quick wit. For example, when sparrows were flying around the Crystal Palace before a big exhibition, he advised Queen Victoria to get "Sparrowhawks, ma'am."

While he is often seen as a defensive general, he led many offensive battles too. However, during much of the Peninsular War, his army was smaller, so he had to be more defensive.

Nicknames

The Iron Duke

This famous nickname refers to his strong and determined political will. It became more popular after 1832, when he installed metal shutters on his home, Apsley House, to protect it from rioters who were angry about his opposition to the Reform Bill.

Other Nicknames

- "Nosey" or "Old Nosey": Used in popular songs of his time.

- "The conqueror of the world's conqueror": This was said by Tsar Alexander I of Russia, referring to Wellington defeating Napoleon.

- "The Beau": His officers called him this because he was a very fine dresser.

- "The Eagle": Spanish troops called him this.

- "Douro Douro": Portuguese troops called him this after his clever river crossing at Oporto in 1809.

- "Sepoy General": Napoleon used this as an insult, trying to make fun of Wellington's service in India.

- "The Beef": Some people believe the dish Beef Wellington is named after him.

- "Europe's Liberator" and "Saviour of the Nations": Other grand titles given to him.

See Also

In Spanish: Duque de Wellington para niños

In Spanish: Duque de Wellington para niños

Images for kids