Daniel O'Connell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Daniel O'Connell

Dónall Ó Conaill |

|

|---|---|

Daniel O'Connell, in an 1836 watercolour by Bernard Mulrenin

|

|

| Member of Parliament for Clare |

|

| In office 5 July 1828 – 29 July 1830 |

|

| Preceded by | William Vesey-FitzGerald |

| Succeeded by | William Macnamara |

| Member of Parliament for Dublin City |

|

| In office 5 August 1837 – 10 July 1841 |

|

| Preceded by | George Hamilton |

| Succeeded by | John West |

| In office 22 December 1832 – 16 May 1836 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir Frederick Shaw |

| Succeeded by | George Hamilton |

| Lord Mayor of Dublin | |

| In office 1841–1842 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir John James, 1st Bt |

| Succeeded by | George Roe |

| Member of Parliament for Cork County |

|

| In office 15 July 1841 – 2 July 1847 |

|

| Preceded by | Garrett Standish Barry |

| Succeeded by | Edmund Burke Roche |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 August 1776 Cahersiveen, County Kerry, Ireland |

| Died | 15 May 1847 (aged 71) Genoa, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | Mary O'Connell (m. 1802) |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | Lincoln's Inn King's Inns |

| Occupation | Barrister, political activist, politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Yeomanry |

| Years of service | 1797 |

| Unit | Lawyer's Artillery Corps |

Daniel O'Connell (born August 6, 1775 – died May 15, 1847) was a very important political leader in Ireland during the early 1800s. People called him The Liberator because he fought for the rights of Irish Catholics. At that time, Catholics in Ireland faced many unfair rules.

O'Connell helped achieve Catholic emancipation in 1829. This meant Catholics could finally become members of the UK Parliament. He was elected twice before this law passed.

Once in Parliament, O'Connell supported many good causes. He was known around the world for fighting against slavery. However, he did not achieve his main goal for Ireland: bringing back a separate Irish Parliament. This was called the "repeal" of the Act of Union.

Towards the end of his life, Ireland faced a terrible time called the Great Famine. O'Connell also had disagreements within his own political movement.

Contents

Early Life and Law Career

Growing Up in Kerry and France

Daniel O'Connell was born in County Kerry, Ireland. His family was wealthy and Catholic. At that time, strict laws called Penal Laws made it hard for Catholics to own land or have power. But O'Connell's family managed to keep their land.

When he was young, Daniel and his brother went to school in France. However, they had to leave quickly in 1793 because of the French Revolution. This experience made O'Connell dislike mob violence for the rest of his life.

Becoming a Lawyer

After studying law in London, O'Connell returned to Ireland in 1795. In 1793, a new law had given Catholics more rights, like being able to vote (though with limits) and work in certain jobs. But Catholics still couldn't be in Parliament or hold high government positions. O'Connell believed the government in Ireland was unfair and only helped a small group of people.

In 1798, O'Connell became a lawyer. Soon after, a group called the United Irishmen started a rebellion, but it failed. O'Connell did not support this rebellion. He believed in peaceful change, not violence. He became a very successful lawyer and earned a lot of money.

His Family Life

In 1802, O'Connell married his cousin, Mary O'Connell. They had four daughters and four sons. All his sons later became Members of Parliament like their father. Their marriage was happy, and Mary's death in 1837 greatly affected O'Connell.

O'Connell's Political Ideas

Beliefs About Government and Religion

O'Connell believed in ideas from the Enlightenment, which focused on reason and individual rights. He thought that public opinion was very powerful and that everyone should have civil liberty and equality.

In Parliament, O'Connell helped pass important laws like the Reform Act of 1832, which changed how people voted, and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which ended slavery in most British colonies. He continued to fight against slavery throughout his life.

O'Connell was a strong Catholic, but he insisted that his political views did not come from Rome. He believed that the Irish Catholic Church was a "national Church" and that it should not be controlled by the government. He famously said that Irish Catholics would rather "remain forever without emancipation" than let the king choose their bishops. He saw the Catholic clergy as important leaders for the Irish people, especially since they were often the only figures independent of the Protestant landlords.

Views on the Irish Language

Even though Irish was O'Connell's first language and spoken by most people in rural areas, he always gave his speeches in English. He would have interpreters translate his words for the crowds.

O'Connell did not seem to think that keeping the Irish language alive was important for his political goals. This view matched the policies of the Catholic Church and government-funded schools at the time, which led to English becoming much more common in Ireland.

Fighting for Catholic Rights

The "Liberator" and Catholic Emancipation

To gain more support for Catholic rights, O'Connell started the Catholic Association in 1823. People could join by paying a small fee, often just a penny a month. This allowed many poor farmers to become part of a national movement for the first time.

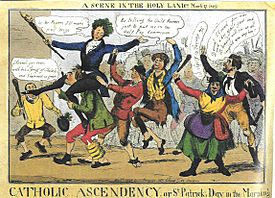

With this support, O'Connell organized huge public meetings, sometimes with over 100,000 people. These "monster rallies" showed the government how strong the movement was. They also encouraged tenants to vote for candidates who supported Catholic rights, even if their landlords disagreed.

In 1828, O'Connell won a special election in County Clare. This was a huge victory because he was Catholic, and Catholics were not allowed to sit in Parliament. His win forced the government to act. Fearing widespread unrest, the government finally passed the Catholic Relief Act in 1829. This law allowed Catholics to become Members of Parliament. O'Connell had to run for election again, but he won easily.

Because of this success, O'Connell became known as "the Liberator." Even King George IV reportedly joked that O'Connell was "King of Ireland."

Tenant Farmers and Tithes

The new law that allowed Catholics into Parliament also changed voting rules. It made it harder for many poorer farmers to vote, reducing the number of Catholic voters. Some critics believed this was done to separate wealthier Catholics from the poorer rural population.

From the 1820s, many tenant farmers faced hardship as landlords cleared land for livestock. Tenants often grouped together to fight evictions and oppose unfair taxes. O'Connell spoke out against these issues. He proposed a tax on landlords who lived outside Ireland and wanted to get rid of "tithes." Tithes were taxes paid to the Anglican Church, even by Catholics, which O'Connell called "the landlords' Church."

A campaign of not paying tithes turned violent in 1831. O'Connell, though against violence, defended those arrested. He helped many accused people get acquitted.

Campaign for Repeal of the Union

What Repeal Meant

O'Connell's next big goal was to "repeal" the Act of Union. This act had joined Ireland and Great Britain into one country in 1801. O'Connell wanted to bring back a separate Irish Parliament. He connected this idea to many common problems faced by the Irish people.

Some historians believe O'Connell might not have expected a full repeal. Instead, he might have used the idea of repeal to pressure the British government into offering some form of self-government for Ireland. He said he would accept a "subordinate parliament" (a parliament with less power) as a first step.

Testing the Union and Reforms

O'Connell tried to work with the British government, especially the Whig party, in the 1830s. He hoped to gain reforms for Ireland.

He was not able to stop the new Poor Law system from coming to Ireland in 1837. This system created workhouses for the poor, which were widely feared. O'Connell argued that poverty in Ireland was due to past unfair laws against Catholics, not high rents. He believed the government should pay for poor relief.

However, O'Connell did have some success. His influence helped more Catholics get jobs in the police and legal system. Steps were also taken to reduce the power of the anti-Catholic Orange Order.

In 1841, O'Connell became the first Roman Catholic Lord Mayor of Dublin in many years. He hoped that city councils would become places where people could learn about peaceful political action.

Disagreements with Other Groups

O'Connell sometimes clashed with other groups, like the Chartists in England, who wanted more democratic rights. He also had disagreements with trade unions. He was worried about violence and tried to control these groups.

Some critics, like Karl Marx, believed O'Connell was trying to keep his followers from joining with other movements that wanted more radical changes.

Renewing the Repeal Campaign

In 1840, O'Connell restarted the Repeal Association. He began criticizing government policies and attacking the Act of Union again.

However, many people, including some Catholics, were not as enthusiastic about repeal as they had been about Catholic Emancipation. They were happy with the new opportunities that emancipation had brought. Protestants, especially in the north of Ireland, generally opposed repeal. They believed the Union helped their prosperity and freedom.

In the 1841 elections, Repeal candidates lost many seats. Despite this, O'Connell was encouraged by support from important figures like Archbishop John McHale. A new newspaper called The Nation also helped spread the message of repeal.

O'Connell then started a new series of "monster meetings," which were huge gatherings of people. These meetings put pressure on the government. O'Connell became famous internationally, gaining support in the United States and France. He declared 1843 "the repeal year," believing Britain would soon give in.

Tara and Clontarf 1843

On August 15, 1843, O'Connell held a massive meeting at the Hill of Tara, a historic site in Ireland. Some reports say nearly a million people attended.

O'Connell planned an even bigger meeting for October 8, 1843, at Clontarf, near Dublin. This site was famous for a battle where Irish forces defeated invaders. O'Connell's speeches were becoming more forceful. However, the government saw this as a threat and sent troops to Clontarf. O'Connell immediately cancelled the rally to avoid violence.

Many people praised O'Connell for preventing bloodshed. But some of his supporters, who had been inspired by his strong words, were disappointed. His reputation suffered, though the government then made a mistake by arresting and sentencing O'Connell and his son for conspiracy.

After three months, they were released when the charges were overturned. O'Connell was celebrated in Dublin, but he was nearly 70 years old and his health was failing. He never fully regained his earlier strength or confidence, and the Repeal Association began to split.

Disagreement with Young Ireland

The Famine and Political Choices

A group called the "Young Irelanders" disagreed with O'Connell on some issues. They believed O'Connell was too willing to make deals with the British government.

Their concerns grew when a new government, led by Lord John Russell, came to power in 1846. This government did not do enough to help with the terrible Irish Famine that was starting.

In February 1847, O'Connell made his last speech in the British Parliament. He pleaded for help for Ireland, saying, "One-fourth of her population will perish unless Parliament comes to their relief." The government did open soup kitchens for a short time but then closed them, telling starving people to go to workhouses.

The Peace Resolutions

After one of the Young Irelanders, Thomas Davis, died, John Mitchel became a more outspoken voice for the group. He suggested that railway tracks could be used as weapons if needed. O'Connell publicly disagreed with these ideas.

In 1847, the Repeal Association passed resolutions saying that a nation was never justified in using force to gain freedom. The Young Irelanders had not openly called for violence, but they argued that if peaceful methods failed, using force could be honorable. O'Connell's son, John, forced the issue, threatening that the O'Connells would leave the Association if the resolution didn't pass.

As a result, many Young Irelanders, including Gavan Duffy and William Smith O'Brien, left the Repeal Association and formed the Irish Confederation.

Later, some of these Confederates did try a small rebellion in 1848, but it quickly failed. Some of them later became part of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a group that believed in using force. Others, like Gavan Duffy, focused on tenant rights, trying to unite people from different backgrounds.

Fighting Against Slavery

O'Connell was a champion of rights for people all over the world. He supported Jewish people in Europe, peasants in India, and native people in New Zealand and Australia. But his strongest stand was against slavery, especially in the United States. This showed his commitment to human rights went beyond just Irish interests.

O'Connell received a lot of money from the United States for his Repeal campaign. However, he insisted that no money should be accepted from anyone involved in slavery. From 1843, he even said that Irish people who supported slavery in America were "no longer Irish." In 1829, he called American slave owners "the most despicable."

In 1838, O'Connell strongly criticized the United States for allowing slavery. He even called the American ambassador a "slave-breeder." This caused a huge stir in America.

Many of his supporters, including some Young Irelanders, thought he should not interfere in American affairs. They believed his strong words were causing problems. However, O'Connell was not afraid. He often spoke about the evils of slavery at his large public meetings.

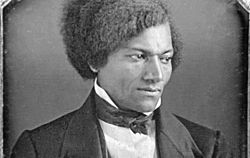

The famous black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond said that hearing O'Connell speak made him truly understand what being an abolitionist meant. William Lloyd Garrison, another leading abolitionist, published O'Connell's anti-slavery speeches, saying no one had spoken more strongly against slavery. O'Connell's favorite author, Charles Dickens, also honored him as an abolitionist in his novel Martin Chuzzlewit.

Death and Legacy

After his last appearance in Parliament, feeling very sad and weak, O'Connell went on a trip to Rome. He died in May 1847 in Genoa, Italy, at the age of 71.

Following his wishes, O'Connell's heart was buried in Rome. The rest of his body was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, under a tall round tower. His sons are also buried there.

No Clear Successor

After O'Connell's death, there was no one with enough experience or respect to lead the Repeal movement. This made it harder for the movement to continue, especially during the difficult time of the Famine.

Memorials and Tributes

After Ireland became independent in 1922, Dublin's main street, Sackville Street, was renamed O'Connell Street in his honor. A statue of him stands at one end of the street.

Many other towns in Ireland also have O'Connell Streets. There is even a Daniel O'Connell Bridge in New Zealand.

In 1929, Irish postage stamps were issued to celebrate 100 years since Catholic Emancipation. There is also a statue of O'Connell outside St Patrick's Cathedral in Melbourne, Australia. His home in Kerry, Derrynane House, is now a museum dedicated to him.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Daniel O'Connell para niños

In Spanish: Daniel O'Connell para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |