John Mitchel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

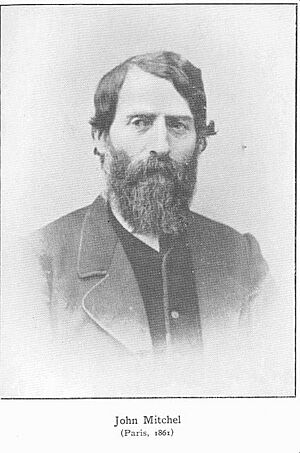

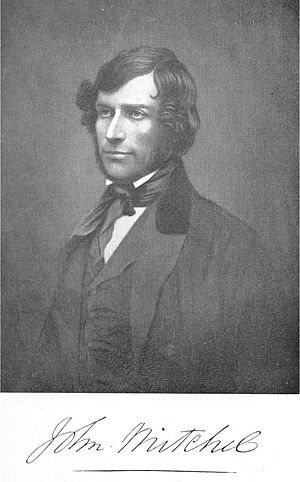

John Mitchel

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 3 November 1815 Camnish, County Londonderry, Ireland.

|

| Died | 20 March 1875 (aged 59) Newry, Ireland

|

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Irish republican and member of the Young Irelanders |

John Mitchel (Irish: Seán Mistéal; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish writer and political activist. He believed Ireland should be free from British rule.

During the terrible Famine years of the 1840s, Mitchel wrote for a newspaper called The Nation. This paper was run by a group called the Young Ireland movement. They wanted Ireland to be independent.

Later, Mitchel started his own newspaper, the United Irishman. In 1848, he was sent away for 14 years. This was because he encouraged Irish people to resist landlords and stop food from being sent to England during the Famine.

After escaping in 1853, Mitchel went to America. There, he surprisingly supported slavery and the Southern states during the American Civil War. This was a very controversial view for someone who fought for freedom in Ireland.

In 1875, the year he died, Mitchel was chosen twice to be a member of the British Parliament for Tipperary. He wanted Ireland to have its own government (called Home Rule), fair tenant rights, and free education. However, he was not allowed to take his seat because he had been found guilty of a crime.

Contents

Early Life in Ireland

John Mitchel was born in Camnish, a small place near Dungiven in County Londonderry, Ireland. His father, Rev. John Mitchel, was a minister. His mother was Mary Haslett.

From 1823, his father became a minister in Newry, County Down. John Mitchel went to school in Newry. He was a very good student. At 15, he went to Trinity College, Dublin, a famous university.

After finishing college at 19, he worked briefly in a bank. Then, he started working in a law office in Newry.

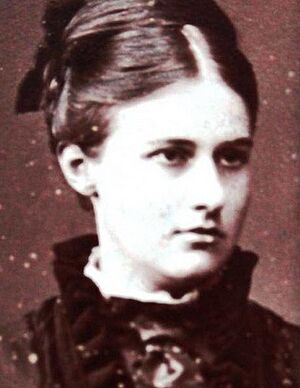

In 1836, Mitchel met Jane "Jenny" Verner. They fell in love and got married in February 1837, even though her family didn't approve at first.

They had four children: John, James, Henrietta, and William. The family moved to Banbridge, County Down, where Mitchel opened a new law office.

Early Steps in Politics

One of Mitchel's first political actions was helping to organize a public dinner in Newry for Daniel O'Connell. O'Connell was a major leader who wanted to cancel the Acts of Union. These acts had joined Ireland and Great Britain.

Mitchel's father had also started to understand the unfair treatment of Irish people. In Banbridge, Mitchel often helped Catholic people in legal cases. These cases often came from conflicts with the Orange Order, a Protestant group. Seeing how unfair the legal system was made Mitchel even more interested in politics.

In 1842, Mitchel received the first copy of The Nation newspaper. It was started by his friends Charles Gavan Duffy and Thomas Osborne Davis. Mitchel thought the newspaper would do well. He also knew that the British Army was sending more soldiers to Ireland.

Working for The Nation Newspaper

Mitchel started writing for The Nation in February 1843. He wrote about Irish language and traditions. He believed these things could unite Irish people, no matter their religion.

When Thomas Davis died in 1845, Charles Gavan Duffy asked Mitchel to become the main writer for The Nation. Mitchel moved his family to Dublin. For the next two years, he wrote many articles about politics and history.

Responding to the Famine

Mitchel strongly blamed the English government for the Famine. He wrote that God sent the potato blight, but "the English created the Famine." He believed that the English government allowed many people to die.

In October 1845, he wrote about the failing potato crop. He warned landlords not to demand rent from their tenants, as this would force them to sell their other food and starve.

He also criticized the government's slow response to the Famine. He pointed out that while Irish people were starving, ships full of Irish grain were sailing to England. He wrote that with every grain, "goes a heavy curse."

Breaking with Daniel O'Connell

In 1846, Daniel O'Connell, who had been working with the British government, saw his efforts to help Ireland fail. He became very ill and died in 1847.

Around this time, Mitchel was influenced by James Fintan Lalor. Lalor believed that Irish independence could only happen if people fought for control of their land. He suggested that people should refuse to pay rent.

Mitchel agreed with Lalor. He wrote that railway tracks could be turned into weapons and trains carrying goods could be stopped. O'Connell disagreed with these ideas and distanced himself from The Nation.

The group around The Nation, called "Young Ireland", then left O'Connell's movement. In 1847, they formed the Irish Confederation. They wanted Ireland to be independent. However, Mitchel soon left this group too. He felt they were not strong enough in their actions.

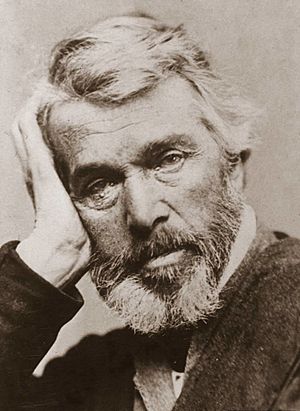

Influence of Thomas Carlyle

Mitchel was influenced by a Scottish writer named Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle had strong ideas about society and leaders. Mitchel reviewed Carlyle's book about Oliver Cromwell. Even though Cromwell had been harsh in Ireland, Mitchel seemed to admire Carlyle's view of him.

Mitchel also wrote a book about an Irish rebel leader, Hugh O'Neill. This book showed Carlyle's influence, as it praised strong leaders and criticized British rule.

Starting The United Irishman

At the end of 1847, Mitchel left The Nation. He believed that a much stronger approach was needed against the English government. He felt the government's Famine policies were designed to control Ireland and harm its people.

Mitchel believed that Irish people should resist the government at every turn. He was not calling for an immediate uprising, as he thought the country was too divided. Instead, he wanted "passive resistance." This meant stopping the transport of Irish food and preventing sales of grain or cattle that landlords seized.

Mitchel's own newspaper, The United Irishman, first came out on 12 February 1848. Its goal was to free Ireland from English rule. The paper declared that Ireland needed to be "swept clear of the English name and nation."

Only 16 issues of The United Irishman were published before Mitchel was arrested and the paper was shut down.

Arrest and Deportation

On 15 April 1848, John Mitchel was accused of trying to cause rebellion. The government changed the charges against him to "Treason Felony," which meant he could be sent away for life.

In May, Mitchel was arrested. In June, he was found guilty by a jury he called "packed" (unfairly chosen). He was sentenced to be sent "beyond the seas for the term of fourteen years." From the courtroom, he said he had shown how unfair the law was in Ireland and that others would follow his path.

Mitchel was first sent to Ireland Island in Bermuda. He was held on a prison ship called HMS Dromedary. He had to wear a prisoner's uniform with his name and number (1922) on his back. The Royal Navy was using prisoners to build a naval base there.

In 1850, Mitchel was sent to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania, Australia). There, he met other Young Irelanders who had been sent away after a small rebellion in 1848. On the ship, he started writing his famous Jail Journal. His wife and children joined him in Tasmania in 1851.

Life in the United States

In 1853, Mitchel escaped from Tasmania with help from a friend. He traveled a long way, through Tahiti, San Francisco, Nicaragua, and Cuba, before reaching New York City.

In New York, he started a newspaper called the Irish Citizen. However, his support for slavery in the Southern states caused a lot of anger and surprise.

Supporting Slavery

Once in the United States, Mitchel openly said that Black people were "innately inferior." He wrote that it was not wrong "to hold slaves, to buy slaves, to keep slaves to their work by flogging or other needful correction." He even said he wished he had "a good plantation well-stocked with healthy negroes in Alabama."

These comments caused a huge public outcry. In Dublin, the Irish Confederation quickly met to say that Mitchel's pro-slavery views were not shared by the Young Ireland group.

Mitchel argued that slavery was "the best state of existence for the negro." He believed it was "good in itself." He even suggested that the trade in enslaved Black people should be reopened.

Mitchel's wife, Jenny, did not agree with him on slavery. She said nothing would make her "the mistress of a slave household." She worried about the harm slavery did to white masters. There is no evidence that Mitchel himself ever owned slaves.

In 1859, Mitchel traveled to Paris. He hoped that a war between France and England might help Ireland. But he found that the talk of war was exaggerated.

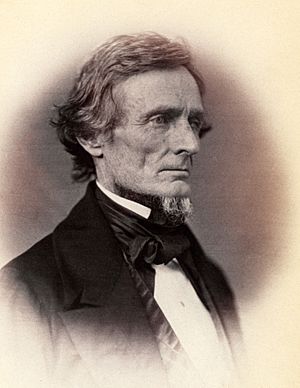

When several Southern states left the American Union in 1861, Mitchel hurried back to the United States. His son John commanded a battery during the attack on Fort Sumter, which started the American Civil War. Mitchel went to Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederate states. There, he edited a newspaper that supported the Confederacy.

Mitchel saw a similarity between the American South and Ireland. Both were farming economies tied to an unfair union. He called Abraham Lincoln "an ignoramus and a boor."

The Mitchels suffered great loss during the war. Their youngest son, Willie, died in the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Their son John died in 1864.

Mitchel continued to support slavery strongly. Even when Confederate generals suggested offering freedom to enslaved people who fought, Mitchel objected. He believed it would mean admitting the South had been wrong from the start.

Disagreements with Irish Americans

After the American Civil War ended in 1864, Mitchel moved to New York. He was arrested for continuing to support the Southern states and was held in Fort Monroe, Virginia. He was released on the condition that he leave America.

Mitchel returned to Paris. By 1867, he was back in New York, restarting his Irish Citizen newspaper.

His views on the post-Civil War period in America, known as Reconstruction, caused more arguments. Other Irish American leaders, like David Bell, criticized Mitchel. Bell argued that Mitchel's ideas would create a new form of slavery for Black people in the South.

Mitchel's newspaper struggled and closed in 1872.

Final Campaign: Tipperary Elections

In July 1874, Mitchel received a warm welcome when he returned to Ireland. Thousands of people greeted him in Cork. Many respected his dedication to Ireland, even if they disagreed with his methods.

Back in New York, Mitchel gave a speech. He said he wanted to run for the British Parliament in Ireland. His goal was to show that Irish representation in Parliament was a "fraud." He also criticized the Irish Home Rule movement, saying they were not truly fighting for Irish freedom.

A chance to run for Parliament came sooner than expected. In January 1875, an election was called for a seat in Tipperary. Mitchel decided to run. He seemed to support Home Rule, along with free education and tenant rights.

On 17 February, while still traveling to Ireland, Mitchel was elected without opposition. However, the British Parliament declared him ineligible because he was a convicted felon. Mitchel ran again in the next election in March 1875 and won with 80 percent of the votes.

John Mitchel died at his parents' house in Newry on 20 March 1875. His last letter thanked the voters of Tipperary for helping him expose the unfair system of Irish representation. At his funeral, his friend John Martin collapsed and died a week later.

Remembering John Mitchel

After Mitchel died, newspapers had different opinions about him. Some acknowledged his love for Ireland but criticized his actions. Others called him a "recreant to liberty" because of his support for slavery.

However, many Irish nationalists, like Pádraic Pearse and Arthur Griffith, praised Mitchel. Pearse called his ideas about Irish nationalism "fiercest and most sublime."

Many Gaelic Athletic Association clubs are named after John Mitchel, including one in his hometown of Newry. Mitchell County, Iowa, in the United States, is also named after him. Fort Mitchel on Spike Island, Cork, where he was held before being transported, is named in his honor.

In 2020, a petition was started to remove a statue of Mitchel in Newry and rename the street it stands on. This was due to his pro-slavery views. Local officials agreed to look into the issue and educate people about it.

Mitchel is remembered for his strong nationalist beliefs and his writings. He was described as "a trumpet to awake the slothful to the call of duty."

Books by John Mitchel

- The Life and Times of Hugh O'Neill, James Duffy, 1845

- Jail Journal, or, Five Years in British Prisons, Office of the "Citizen", New York, 1854

- Poems of James Clarence Mangan (Introduction), P. M. Haverty, New York, 1859

- An Apology for the British Government in Ireland, Irish National Publishing Association, 1860

- The History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the Present Time, Cameron & Ferguson, Glasgow, 1864

- The Poems of Thomas Davis (Introduction), D. & J. Sadlier & Co., New York, 1866

- The Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps), Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873 (originally appeared in the Southern Citizen, 1858)

- The Crusade of the Period, Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873

- Reply to the Falsification of History by James Anthony Froude, Entitled 'The English in Ireland', Cameron & Ferguson n.d.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |