Young Ireland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Young Ireland

|

|

|---|---|

Irish tricolour raised in the Young Ireland rebellion 1848

|

|

| Founded | 1842 |

| Dissolved | 1849 |

| Preceded by | Repeal Association |

| Succeeded by | Tenant Right League, Irish Republican Brotherhood |

| Newspaper | The Nation |

| Ideology | Irish nationalism Liberalism Radicalism Land reform |

| National affiliation | Repeal Association (1842–1847) Irish Confederation (1847–1848) |

| Colours | Green, White and Orange |

| Slogan | A Nation Once Again |

Young Ireland (Irish: Éire Óg, IPA: [ˈeːɾʲə ˈoːɡ]) was a group of young people in the 1840s. They wanted Ireland to be independent and have democratic reforms. They gathered around their newspaper, The Nation. This group disagreed with the older, larger movement led by Daniel O'Connell, called the Repeal Association. Young Ireland left O'Connell's group in 1847.

During the terrible Great Irish Famine, the Young Irelanders tried to start a rebellion in 1848. Many of their leaders were arrested or sent away from Ireland. After this, the movement split. Some members continued to believe in using force, and later helped form the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Others wanted to work for land reform and create a strong Irish political party.

Contents

How Young Ireland Started

Student Debates at Trinity College

Many future Young Irelanders first met in 1839. They were part of the College Historical Society in Dublin. This student club at Trinity College Dublin had a long history. Students there had debated ideas about Irish patriotism for many years. Famous Irish figures like Theobald Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet were once members. The club had been kicked out of the college before for discussing "modern politics."

The group that met in 1839 was a mix of people. It included Catholics, who had only been allowed into Trinity College since 1793. Among them were Thomas MacNevin and John Blake Dillon. Other important future Young Irelanders present were Thomas Davis and John Mitchel.

Joining the Repeal Association

These young men, along with others, joined Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. In 1840, O'Connell restarted his campaign. He wanted to bring back an Irish parliament in Dublin. This meant repealing, or undoing, the Act of Union 1800. This Act had joined Ireland and Great Britain.

In April 1841, O'Connell gave Davis and Dillon important roles. They were in charge of organizing and finding new members for his Association. But getting new members was slow at first.

Many people in the south and west of Ireland did not join. These were the tenant farmers and traders who had supported O'Connell before. They had helped him win Catholic Emancipation in the 1820s. But they were not as interested in the idea of Repeal. In the north-east, many Protestants believed that staying united with Great Britain was better for them. They thought it brought wealth and freedom. So, most Protestants were against bringing back an Irish parliament.

Working with O'Connell was not always easy. He did not like people disagreeing with him. Davis and Dillon found an ally in Charles Gavan Duffy. Duffy was the editor of a Repeal newspaper in Belfast.

The Nation Newspaper

Duffy suggested starting a new national newspaper. He wanted to own it, but Davis and Dillon would help run it. The paper first came out in October 1842. Davis chose its name, The Nation. It was named after a French newspaper.

The newspaper's goal was to guide people's thoughts. It wanted to unite people of all backgrounds for Irish independence. It aimed to help Irish people escape poverty. It also wanted to inspire a strong love for their country.

The Nation was an instant success. It sold more copies than any other Irish newspaper. At its peak, about a quarter of a million copies were read. The paper focused on opinion pieces, history articles, and poems. People read copies in special reading rooms. They also passed them from person to person. This meant the paper was read long after it was first published.

The paper brought in many new writers. These included:

- William Smith O'Brien, a member of parliament.

- James Fintan Lalor, a land rights activist.

- Michael Doheny, a writer.

- William Carleton, who wrote about Irish country life.

- Father John Kenyon, a nationalist priest.

- Jane Wilde, a poet and early supporter of women's rights.

- Thomas Devin Reilly, a republican and worker's rights activist.

- Thomas D'Arcy McGee, a former American journalist.

- Thomas Francis Meagher, a famous speaker.

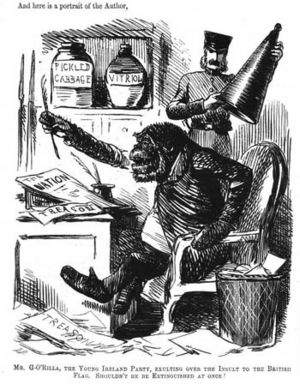

An English journalist first called this group "Young Ireland." This name was a nod to similar movements in Europe. These included "Young Italy" and "Young Germany." Later, O'Connell himself started calling them "Young Irelanders." This was a sign that a disagreement was coming.

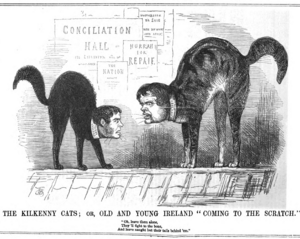

Disagreements with O'Connell

Stopping the Repeal Meeting

The Nation newspaper supported O'Connell in October 1843. This was when he called off a huge Repeal meeting at Clontarf. The government had sent soldiers and cannons to stop the meeting. O'Connell had planned it as the last "monster meeting" for Repeal. Earlier, a meeting at the Hill of Tara had drawn nearly a million people.

O'Connell gave in right away. He canceled the rally and sent messengers to turn people back. Duffy felt this decision made the Repeal movement less powerful. But the Young Irelanders agreed that avoiding a massacre was important. The government then charged O'Connell, his son John, and Duffy with trying to cause trouble. They were released after three months. Davis and O'Brien then organized a huge welcome for O'Connell in Dublin.

The first sign of a split came when Duffy asked O'Connell to confirm his goal was full Repeal. O'Connell said he would never ask for less than an independent parliament. But he also hinted he might accept a "subordinate parliament." This would be an Irish law-making body with less power, given by the British parliament.

A more serious disagreement happened with Davis. Davis had been talking about a less powerful parliament with a reformer from the North. The difference was that Davis wanted to find common ground in Ireland, not just in London.

Including Protestants

Duffy admitted he once wanted to bring back only the "Celtic race and the Catholic church." But in The Nation, he supported a wider vision. Davis wrote that Irish nationality should include "the stranger" as well as "the Irishman of a hundred generations."

Davis believed that nationality was not about family history. It was about shared culture and language. He thought these could unite people from different backgrounds.

Davis strongly promoted the Irish language. At that time, most Irish people spoke it. But educated people had almost stopped using it. O'Connell did not seem interested in this cultural nationalism. He did not see preserving the Irish language as key to his political goals. His own newspaper focused on religion as the main difference between English and Irish people.

O'Connell valued the few Protestants who supported Repeal. But he relied on Catholic priests to lead his movement. In many parts of Ireland, priests were the only important figures not controlled by the government. The Repeal Association, like earlier Catholic groups, was built on this.

In 1845, O'Connell spoke out against a plan for non-religious colleges. He wanted separate colleges for Catholics. Davis disagreed, saying that separate education would lead to separate lives. O'Connell accused Davis of saying it was wrong to be Catholic. He declared, "I am for Old Ireland, and I have some slight notion that Old Ireland will stand by me."

O'Connell rarely spoke about the Irish Rebellion of 1798. This rebellion had tried to unite "Catholic, Protestant, and Dissenter." O'Connell looked to liberal England for an Irish parliament, not to Protestant Ulster. He thought that once an Irish parliament was back, Protestants would join the large Catholic majority.

Whig Government and the Famine

Thomas Davis died suddenly in 1845. This helped calm the argument. But his friends thought O'Connell's strong opposition was also meant to help the Whig party. Meagher argued that this strategy had not helped Ireland. The last gain from the Whig government was municipal reform in 1840. This allowed O'Connell to become Lord Mayor of Dublin. But it left most people under the control of landlords.

In June 1846, the Whig party came back into power. They quickly stopped the limited efforts to help with the growing Irish Famine. The government believed in "laissez-faire" ideas. This meant they thought the economy should be left alone. O'Connell had to beg for his country in the House of Commons. He said, "One-fourth of her population will perish unless Parliament comes to their relief." O'Connell was a broken man. He went to Europe for his health and died in May 1847.

The Peace Resolutions

Before O'Connell died, Duffy shared letters from James Fintan Lalor. Lalor believed that independence could only come from a fight for land. He thought this would unite North and South. He said that Young Irelanders should be ready for a "moral insurrection." He suggested a campaign to stop paying rent. Some parts of the country were already in a state of unrest. Tenants were attacking officials and resisting evictions. Lalor warned against a general uprising. He thought the people could not win against the British army.

Lalor's letters greatly influenced John Mitchel and Father John Kenyon. When a newspaper said new railways could move troops to stop unrest, Mitchel replied that tracks could become weapons. O'Connell publicly distanced himself from The Nation. This seemed to set Duffy up for legal trouble. When the courts did not convict Duffy, O'Connell pushed the issue. He seemed determined to cause a split.

In July 1846, the Repeal Association passed resolutions. They stated that a nation was never justified in using force to gain freedom. Meagher argued that Young Irelanders were not promoting force. But he said if peaceful means failed, using arms would be honorable. O'Connell's son, John, forced the decision. The resolution passed because the O'Connells threatened to leave the Association.

Offers to settle the dispute between Old and Young Ireland were rejected.

The Irish Confederation

Forming a New Group

The Young Irelanders left the Repeal Association. But they had a lot of support. In October 1846, many important citizens in Dublin protested their exclusion. In January 1847, the Young Irelanders formed the Irish Confederation. Michael Doheny remembered that they did not declare rebellion. Their goals were "independence of the Irish nation." They would use any means to reach this goal, as long as it was honorable and reasonable.

In the Shadow of the Famine

At first, Duffy directed Confederate clubs to promote Irish goods. They also worked to expand voting rights. They taught young people about Irish history. Village clubs promoted the rights of tenants and workers. They also shared farming knowledge. They tried to encourage peace and discourage secret societies. All clubs aimed to create harmony among Irish people of all religions. They especially invited Protestants to join. But in 1847, the worst year of the Famine, they looked for ways to help immediately.

The Confederation urged farmers to keep their harvest for their families first. But Duffy later admitted that the poorest people only knew how to grow potatoes. Even if they kept other food, they might still be evicted. In spring 1847, the government opened soup kitchens. But they closed them in August. Starving people were told to leave their land and go to workhouses.

Mitchel urged the Confederation to adopt Lalor's policy. This policy would make land control the main issue. However, Duffy stopped Mitchel from writing in The Nation. Mitchel had written articles supporting slavery and opposing Jewish rights in the United States. These views were very different from O'Connell's.

In February 1848, Mitchel started his own newspaper, The United Irishman. It openly supported Lalor's ideas. In May, Mitchel was found guilty of a new crime, treason felony. He was sent away for 14 years to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania, Australia).

Land Rights or Parliament?

Duffy remembered an old Quaker who was a United Irishman. He said that kings and governments were not the real issue. What mattered was the land, which gave people their food. He thought the French had the right idea: kicking out landlords and putting tenants in their place. But Duffy felt Lalor's "angry peasants" were not real. He also wanted to keep a wider group together. So, he made O'Brien, a Protestant landowner, the leader.

The Confederation's Council voted to support Duffy's idea. This was to form a Parliamentary Party. This party would accept no favors. It would push Ireland's demands by stopping all business in the British Parliament. This party would either get its demands met or be forced out of Westminster. If forced out, the people would then know how to act. Mitchel and Thomas Devin Reilly disagreed. They believed past attempts at such groups had failed. They still wanted Lalor's plan.

The Path to Rebellion

Duffy's Beliefs

By spring 1848, everyone on the Council agreed. Irish independence was vital. An Irish national government was needed to control resources. In May 1848, Duffy published "The Creed of the Nation." It said that if Ireland gained independence by force, it would be a Republic. He hoped to avoid deadly fights among Irish people.

Duffy wrote that an independent Irish parliament would be enough. It would have wide voting rights and an Irish leader. Such a parliament would give tenants more rights. It would also help workers. Other European countries were protected from starvation because their rulers were "of their own blood and race." This was not true for Ireland, which was why it faced such tragedy.

The government made it clear they would use force, not compromise. Mitchel had been convicted under new laws. On July 9, 1848, Duffy was arrested for trying to cause trouble. He managed to send a message to The Nation. He said there was no solution now but fighting. But the newspaper issue with his message was seized, and the paper was shut down.

The 1848 Uprising

Plans for a rebellion were already moving forward. Mitchel had called for action but did not plan well. O'Brien, to Duffy's surprise, tried to organize it. In March, he visited revolutionary Paris. He hoped for French help. There was also talk of an Irish-American group and a Chartist protest in England. The Confederation had strong support in English cities like Liverpool. With Duffy's arrest, O'Brien faced the reality of how alone they were in Ireland.

On July 23, O'Brien, Meagher, and Dillon gathered a small group. They raised the flag of revolt in Kilkenny. This was a tricolour flag O'Brien brought from France. Its green, white, and orange colors symbolized the unity of Catholics and Protestants.

The Confederates had no organized support in the countryside. This was because the older Repeal group and most priests were against them. Their active members were only in the towns. As O'Brien went into Tipperary, curious crowds met him. But he only had a few hundred poorly dressed, mostly unarmed men. They scattered after a small fight with the police. This fight was jokingly called "Battle of Widow McCormack's Cabbage Patch."

O'Brien and his friends were quickly arrested. They were found guilty of treason. After many public protests, the government changed their death sentences. They were sent to Van Diemen's Land, where they joined John Mitchel. Only Duffy escaped conviction. Thanks to a Catholic juror and a good lawyer, Duffy was released in February 1849. He was the only major Young Ireland leader left in Ireland.

John Devoy, a later Fenian, said the rebellion was "little short of insanity." He felt the Famine forced the Young Irelanders to act without military preparation. However, James Connolly argued that people in towns would have fought if given the signal. He wrote that when Duffy was arrested, Dublin workers offered to start a rebellion. But Duffy refused. In Cashel, people rescued Michael Doheny from jail. But he gave himself up again. In Waterford, people stopped the soldiers carrying Meagher. They begged him to give the word to fight. But Meagher insisted on going with the soldiers.

What Happened Next

The League of North and South

James Fintan Lalor believed the Famine showed that landlordism was wrong. In September 1849, Lalor tried to restart the rebellion. He worked with John Savage and Joseph Brenan. They tried in Tipperary and Waterford. After a small fight, the rebels broke up because there were so few of them. Lalor died three months later.

Tenant farmers were not ready to fight for a republic. But they started to form groups to protect their interests. Duffy wanted to connect these new tenant groups to his idea of an independent parliamentary party. In August 1850, Duffy helped form the Tenant Right League. This group included tenant representatives, magistrates, landlords, Catholic priests, and Presbyterian ministers.

In the 1852 election, the League helped elect Duffy and 47 other members of parliament. These MPs promised to fight for tenant rights. Duffy called this the "League of North and South." But it was not as strong as it seemed. Many MPs had already been in parliament. Only one MP from Ulster was elected.

After a small land bill was defeated, the "Independent Irish Party" began to fall apart. The Catholic Archbishop Paul Cullen allowed the MPs to break their promise. They accepted jobs in a new government. In the North, meetings were broken up by anti-Catholic groups.

Duffy was tired and sick. In 1855, he announced he was leaving parliament. He felt he could no longer achieve his goals. He moved to Australia. Later, the Land League and Irish Parliamentary Party achieved what he had wanted. They combined farmer protests with political action in Westminster.

Irish Republican Brotherhood

Some of the "Men of 1848" continued to believe in using force. They helped form the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in 1858 in Dublin. A similar group, the Fenian Brotherhood, was started by Meagher and other exiles in the United States. In 1867, the Fenians, many of whom were Irish veterans of the American Civil War, raided Canada. They hoped to use Canada to gain Irish Independence. At the same time, the IRB tried an armed uprising in Ireland.

The IRB continued to get important support from Irish people living in the United States. They played a key role in raising the Young Irelander tricolour flag over Dublin in the Easter Rising of 1916.

Important Young Irelanders

See also

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |