Easter Rising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Easter RisingÉirí Amach na Cásca |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Irish revolutionary period | |||||||

O'Connell Street, Dublin, after the Rising. The GPO is at left, and Nelson's Pillar at right. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

16,000 British troops and 1,000 armed RIC in Dublin by the end of the week | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

The Easter Rising (Irish: Éirí Amach na Cásca) was a major rebellion in Dublin, Ireland, in 1916. It was led by Irish republicans who wanted Ireland to be a free country. They aimed to create a republic, meaning a nation ruled by elected leaders, not a king or queen.

This event was the most important uprising in Ireland since 1798. It marked the first armed conflict of the Irish revolutionary period. Many of the Rising's leaders were executed, which made many more people support Irish independence.

Contents

When Was the Easter Rising?

The Easter Rising began on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916. It lasted for six days, ending on April 29, 1916. The rebels chose Easter, a special holiday, hoping it would make a big impact.

Who Was Involved in the Rising?

Several groups of Irish republicans worked together to plan the Easter Rising. Here are the main groups and some key people:

- The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB): This was a secret group. They wanted to end British rule and create an Irish republic.

- The Irish Volunteers: This was a military group. They formed to defend Ireland and fight for its freedom.

- The Irish Citizen Army: This group was started by workers. They aimed to protect workers' rights and fight for a socialist republic. This meant a country where the government controls the economy.

Key Leaders of the Easter Rising

Some of the most important leaders of the Easter Rising were:

- Patrick Pearse: He was a teacher and poet. He was a main leader of the IRB. He read the Proclamation of Irish Independence.

- James Connolly: He was a socialist leader. He commanded the Irish Citizen Army. He fought for both Irish freedom and workers' rights.

- Thomas Clarke: A long-time republican. He had tried to gain Irish independence before.

- Seán Mac Diarmada: He was a key organizer for the IRB.

- Éamonn Ceannt: He was part of the IRB's military committee.

- Thomas MacDonagh: A poet and writer who joined the rebellion.

- Joseph Plunkett: A poet and planner who helped organize the Rising.

Why Did the Rebels Fight?

The people who took part in the Easter Rising had several reasons to rebel against British rule:

- Desire for Independence: They strongly believed Ireland should govern itself. They wanted to be free from British control.

- Frustration with British Rule: They felt the British government did not understand or care about Irish people's needs.

- Inspired by Irish History: They looked back at Ireland's past. Many times, Irish people had fought for their freedom.

- Influence of Irish Culture: There was a new interest in Irish language and culture. This made people feel proud and want independence.

What Happened During the Rising?

On Easter Monday, about 1,600 rebels took over important buildings in Dublin. These included:

- The General Post Office (GPO): This became the rebels' main base. Patrick Pearse read the Proclamation of Irish Independence from its steps.

- The Four Courts: A large group of law courts.

- Boland's Mill: A key location that controlled city access.

- St. Stephen's Green: A park in the city center.

The rebels held these buildings. They fought against the British army. The British had many more soldiers and better equipment. The fighting was fierce, and many people were killed or hurt.

The Proclamation of Irish Independence

A very important event during the Easter Rising was the reading of the Proclamation of Irish Independence. This document declared Ireland a free and independent republic. It said that all Irish citizens were equal. It promised religious freedom, civil liberty, and equal rights for everyone. The seven leaders of the Rising signed the Proclamation. It was posted on the walls of the GPO.

How Did the Rising End?

After six days of fighting, the rebels had to surrender. The British army had surrounded them. They were using heavy guns to attack the buildings the rebels held. The leaders knew they could not win. They wanted to stop more people from dying.

What Happened After the Rising?

After the surrender, the British government arrested thousands of people. These were people they thought were involved in the Rising. The leaders were tried in a military court. They were sentenced to death.

Between May 3 and May 12, 1916, fifteen leaders were executed by firing squad. These executions made many Irish people very angry. Many who had not supported the Rising before now saw the leaders as heroes. They were seen as martyrs, people who die for their beliefs. The Easter Rising was a main reason for the creation of the Irish Republic and the Irish War of Independence.

Impact of the Easter Rising

Even though the Easter Rising failed militarily, it had a huge impact. It helped unite the Irish people. They became more determined to gain independence. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921). This war eventually helped Ireland gain its freedom from British rule.

The Easter Rising is remembered today as a brave and important event. It is a key part of Ireland's fight for freedom. The leaders are honored as heroes who gave their lives for their country.

Key Facts and Figures

- Date: April 24-29, 1916

- Location: Dublin, Ireland

- Participants: Irish republicans (Irish Volunteers, Irish Citizen Army, IRB) vs. British Army

- Number of Rebels: Around 1,600

- Number of British Soldiers: Around 20,000

- Casualties:

- Rebels: About 83 killed

- British Army: About 130 killed

- Civilians: About 254 killed

- Leaders Executed: 15

- Key Buildings Seized: General Post Office (GPO), Four Courts, Boland's Mill, St. Stephen's Green

Images for kids

-

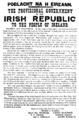

Proclamation of the Republic, Easter 1916

-

The General Post Office in Dublin – the rebel headquarters

-

British soldiers searching the River Tolka in Dublin for arms and ammunition after the Easter Rising. May 1916

-

Plaque commemorating the Easter Rising at the General Post Office, Dublin, with the Irish text in Gaelic script, and the English text in regular Latin script

-

Memorial in Cobh, County Cork, to the Volunteers from that town

-

Mural in Belfast depicting the Easter Rising of 1916

-

Memorial in Clonmacnoise commemorating men of County Offaly (then King's County) who fought in 1916: James Kenny, Kieran Kenny and Paddy McDonnell are named

See also

In Spanish: Alzamiento de Pascua para niños

In Spanish: Alzamiento de Pascua para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |